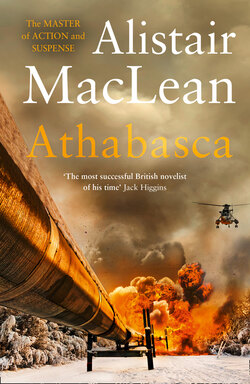

Читать книгу Athabasca - Alistair MacLean, Alistair MacLean, John Denis - Страница 6

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеThis book is not primarily about oil, but is based on oil and the means whereby oil is recovered from the earth, so it may be of some interest and help to look briefly at these phenomena.

What oil is, and how it is formed in the first place, no one quite seems to know. The technical books and treatises on this subject are legion – I am aware that, personally, I haven’t seen a fraction of them – and they are largely, so I am assured, in close agreement – except when they come to what one would have thought was a point of considerable interest: how, precisely, does oil become oil? There appear to be as many divergent theories about this as there are about the origins of life. Confronted with complexities, the well-advised layman takes refuge in over-simplification – which is what I now do, as I can do no other.

Only two elements were needed for the formation of oil – rock, and the incredibly abundant plants and primitive living organisms that teemed in rivers, lakes and seas as far back as perhaps a billion years ago. Hence the term fossil fuels.

The Biblical references to the rock of ages give rise to misconceptions about the nature and permanency of rock. Rock – the material of which the earth’s crust is made – is neither eternal nor indestructible. Nor is it even unchanging. On the contrary, it is in a state of constant change, movement and flux, and it is salutary to remind ourselves that there was a time when no rock existed. Even today there is a singular lack of agreement among geologists, geo-physicists and astronomers as to how the earth came into being; but there is a measure of agreement that there was a primary incandescent and gaseous state, followed by a molten state, neither of which was conducive to the formation of anything, rock included. It is erroneous to suppose that rock has been, is and ever shall be.

Yet we are not concerned here with the ultimate origins of rock, but rock as we have it today. It is, admittedly, difficult to observe this process of flux, because a minor change may take ten million years, a major change a hundred million.

Rock is constantly being destroyed and rebuilt. In the destructive process weather is the main factor; in the rebuilding, the force of gravity.

Five main weather elements act upon rock. Frost and ice fracture rock. It can be gradually eroded by airborne dust. The action of the seas, whether through the constant movement of waves and tides or the pounding of heavy storm waves, remorselessly wears away the coastlines. Rivers are immensely powerful destructive agencies – one has but to look at the Grand Canyon to appreciate their enormous power; and such rocks as escape all these influences are worn away over the aeons by the effect of rain.

Whatever the cause of erosion, the end result is the same: the rock is reduced to its tiniest possible constituents – rock particles or, simply, dust. Rain and melting snow carry this dust down to the tiniest rivulets and the mightiest rivers, which in turn transport it to lakes, inland seas and the coastal regions of the oceans. Dust, however fine and powdery, is still heavier than water, and whenever the water becomes sufficiently still, it will gradually sink to the bottom, not only in lakes and seas but also in the sluggish lower reaches of rivers and, where flood conditions exist, inland in the form of silt.

And so, over unimaginably long reaches of time, whole mountain ranges are carried down to the seas and in the process, through the effects of gravity, new rock is born as layer after layer of dust accumulates on the bottom, building up to a depth of ten, a hundred, perhaps even a thousand feet, the lowermost layers being gradually compacted by the immense and steadily-increasing pressures from above, until the particles fuse together and re-form as new rock.

It is in the intermediate and final processes of this new rock formation that oil comes into being. Those lakes and seas of hundreds of millions of years ago were almost choked by water plants and the most primitive forms of aquatic life. On dying, they sank to the bottom of the lakes and seas along with the settling dust particles and were gradually buried deep under the endless layers of more dust and more aquatic and plant life that slowly accumulated above them. The passing of millions of years and the steadily increasing pressures from above gradually changed the decayed vegetation and dead aquatic life into oil.

Described thus simply and quickly, the process sounds reasonable enough. But this is where the grey and disputatious area arises. The conditions necessary for the formation of oil are known: the cause of the metamorphosis is not. It seems probable that some form of chemical catalyst is involved, but this catalyst has not been isolated. The first purely synthetic oil, as distinct from secondary synthetic oils such as those derived from coal, has yet to be produced. We just have to accept that oil is oil, that it is there, bound up in rock strata in fairly well-defined areas throughout the world but always on the sites of ancient seas and lakes, some of which are now continental land, some buried deep under the encroachment of new oceans.

Had the oil remained intermingled with those deeply-buried rock strata, and were the earth a stable place, that oil would have been irrecoverable. But our planet is a highly unstable place. There is no such thing as a stable continent securely anchored to the core of the earth. The continents rest on the so-called tectonic plates which, in turn, float on the molten magma below, with neither anchor nor rudder, free to wander in whichever haphazard fashion they will. This they unquestionably do: they are much given to banging into each other, grinding alongside each other, overriding or dipping under each other in a wholly unpredictable fashion and, in general, resembling rocks in the demonstration of their fundamental instability. As this banging and clashing takes place over periods of tens or hundreds of millions of years, it is not readily apparent to us except in the form of earthquakes, which generally occur where two tectonic plates are in contention.

The collision of two such plates engenders incredible pressures, and two of the effects of such pressures are of particular concern here. In the first place the huge compressive forces involved tend to squeeze the oil from the rock strata in which it is embedded and to disperse it in whichever direction the pressure permits – up, down or sideways. Secondly, a collision buckles or folds the rock strata themselves, the upper strata being forced upwards to form mountain ranges – the northern movement of the Indian tectonic plate created the Himalayas – and the lower strata buckling to create what are virtually subterranean mountains, folding the layered strata into massive domes and arches.

It is at this point, insofar as oil recovery is concerned, that the nature of the rocks themselves becomes of importance. The rock can be porous or non-porous, the porous rock – such as gypsum – permitting liquids, such as oil, to pass through them, while the non-porous – such as granite – does not. In the case of porous rock the oil, influenced by those compressive forces, will seep upwards through the rock until the distributive pressure eases, when it will come to rest at or very close to the surface of the earth. In the case of non-porous rock, the oil will become trapped in a dome or arch, and in spite of the great pressures from below can escape neither sideways nor upwards but must remain where it is.

In this latter case what are regarded as conventional methods are used in the recovery of oil. Geologists locate a dome, and a hole is drilled. With reasonable luck they hit an oil dome and not a solid one, and their problems are over – the powerful subterranean pressures normally drive the oil to the surface.

The recovery of seepage oil which has passed upwards through porous rock presents a quite different and far more formidable problem, the answer to which was not found until as late as 1967. Even then it was only a partial answer. The trouble, of course, is that this surface seepage oil does not collect in pools, but is inextricably intermixed with foreign matter such as sand and clay from which it has to be abstracted and refined.

It is, in fact, a solid and has to be mined as such; and although this solidified oil may go as deep as six thousand feet, only the first two hundred feet, in the limits of present-day knowledge and techniques, are accessible, and that only by surface mining. Conventional mining methods – the sinking of vertical shafts and the driving of horizontal galleries – would be hopelessly inadequate, as they would provide only the tiniest fraction of the raw material required to make the extraction process commercially viable. The latest oil extraction plant, which went into operation only in the summer of 1978, requires 10,000 tons of raw material every hour.

Two excellent examples of the two different methods of oil recovery are to be found in the far north-west of North America. The conventional method of deep drilling is well exemplified by the Prudhoe Bay oilfield on the Arctic shore of northern Alaska; its latter-day counterpart, the surface mining of oil, is to be found – and, indeed, it is the only place in the world where it can be found – in the tar sands of Athabasca.