Читать книгу Trekking in the Zillertal Alps - Allan Hartley - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

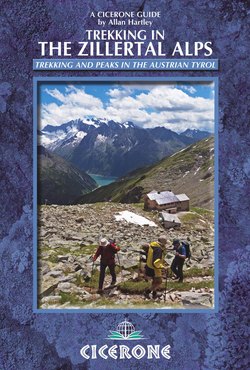

Ascent of the Ahorn Spitze on the track just above the Edel Hut (end of ZRR Stage 1)

In the heart of the pristine Austrian Tyrol rise the shapely, snow-capped peaks of the Zillertal Alps. Dotted with top-quality huts connected by clear paths, they offer a premier trekking region for novices and for experts.

The Zillertal Alps are located entirely within the Austrian province of the Tyrol. To the east, the Zillertal merges with the mountains of the Reichen and Venediger Groups and the province of Ost (East) Tyrol; to the west is the Brenner Pass into Italy and the mountains of the Stubai Alps. Southwards are Italy and the South Tyrol, along with the mountains at the head of the Zillertal valley which, together with its huts, was annexed to Italy at the end of the First World War. To the north is the Inn valley, which runs the entire length of the Tyrol. The Zillertal is the longest subsidiary valley in the Tyrol at some 50km long, and terminates at the picturesque and popular holiday resort town of Mayrhofen.

Above Mayrhofen the main Zillertal valley splits off into a number of subsidiary valleys, and they in turn also branch off in various directions. To the east is the steeply sided Zillergrund valley, flanked by the Ahorn Spitze and Brandberg Kolm, with the village of Brandberg and farming hamlets of Inder Au and Barenbad leading to the Zillergrund reservoir and the old cattle drovers’ trail into the Ahrntal valley of Italy and the South Tyrol.

To the west are the villages of Finkenberg and Hintertux and the mountains of the Tuxer Hauptkamm and the Hintertux valley, flanked by the peaks of the Grindberg Spitze to the south and Tuxer Alpen to the north, with the Penkenjoch and Rastkogel. To the southwest is the main Zamsergrund valley and the delightful village of Ginzling and hamlet of Breitlahner, beyond which the road terminates at the head of the Zamsergrund valley by the Schlegeisspeicher hydro-electric reservoir and the ancient trade route into the Pfitschertal valley of Italy and the South Tyrol via Pfitscherjoch.

Immediately to the south of Mayrhofen are the peaks of the Ahorn Spitze, Dristner and the bulk of the Grindberg Spitze – all stand tall and are unmissable from the railway station. Above the tree line the horizon to the south is dominated by the peaks sharing the border with Italy and the South Tyrol, particularly the Hochfeiler, Grosser Moseler and Schwarzenstein, profiles that will become familiar features of your trek.

The Rucksack Route and South Tyrol Tour

The Zillertal Rucksack Route (ZRR), also known as the Berliner Hoehenweg (German) or Zillertaler Runde Tour (Austrian), is a hut-to-hut tour that starts above Mayrhofen from the Karl von Edel Hut and then visits each of the following huts in turn, Kasseler, Greizer, Berliner, Furtschagl Haus, Olperer, Friesenberg Haus to end at the Gams Hut high above the charming village of Ginzling before returning to Mayrhofen. This gives a continuous walk of about ten days, which can be extended to include ascents of the local peaks, Klettersteige rock scramble adventures (on via ferrata-type protected routes), and even rest days. The length of the tour is 70–80km, depending on where you start and finish, and it ascends some 6700m.

As the name suggests, the Rucksack Route can be traversed entirely without crossing glaciers and without specialist climbing skills. However, it does involve negotiating steep ground, crossing late summer snow and making use of fixed wire ropes here and there that are installed to aid stability. To climb some of the peaks described in the ‘Excursion’ sections of the guide, it is necessary to make glacier crossings, for which the required skills and kit are essential (see ‘Alpine walking skills and equipment’ below).

The Zillertal South Tyrol Tour (ZSTT) is virtually unknown outside the South Tyrol, which is one of the key ingredients that helps to make it interesting and different. The tour starts from the Bergbauernhof farmstead at Touristenraste, not far from the small industrial town of Steinach am Brenner. From Touristenraste it first progresses to the Geraer Hut, and then enters the Zillertal and South Tyrol proper at Pfitscherjoch Haus on the border with Italy. (Conveniently, Pfitscherjoch Haus also provides an alternative starting point for those wishing to join the tour from Mayrhofen and the Zillertal valley.) From Pfitscherjoch Haus the tour heads for the historic Hochfeiler Hut, and continues by way of the Edelraute, Nevesjoch and Schwarzenstein Huts before returning to Austria across the Schwarzensteinkees or Floitenkees glaciers to either the Berliner or Greizer Hut. From both huts, there is access to Mayrhofen and onward transport.

Excluding the peaks, this gives a continuous hut-to-hut tour of eight days, with good opportunities along the way to climb the Hochfeiler and Grosser Moseler, two of the Zillertal’s most prestigious mountains. Overall the tour is about 55km long and ascends just over 5000m (without considering climbing any peaks). It is physically demanding and will perhaps appeal to more experienced alpine walkers who wish to undertake a tour that is more remote and challenging.

The Zillertal’s highest peak is the Hochfeiler (3510m), and there are a further 40 peaks over 3000m, many of which are glaciated or have permanent snow cover. The Zillertal arena provides ample opportunity for all mountain enthusiasts. It is ideal for first-time visitors to the Alps (with the ZRR being particularly suitable for capable family groups with children) and for aspiring alpinists.

However, it should be remembered that the Zillertal is not necessarily a tame area in comparison with the Western Alps, as these mountains can challenge even the most experienced. Whatever your aspirations, you will not be disappointed.

Gruss Gott und sehr gut Zillerbergtouren.

When to go

The Hochfeiler (3510m), highest peak in the Zillertal (end of STT Stage 3)

The summer season usually starts in mid-June, when the huts open, and ends in late September, when the huts close. During this time the paths and passes are relatively free of snow.

June is early season and not the best time to visit, as it is not unusual to come across large amounts of old snow lying on north-facing slopes, such as those of the Lapen Scharte.

In July, the weather is warmer and the winter snow further recedes, although there are more people in the mountains and at the huts.

August is seen as the peak season when most Europeans take their holidays. The huts are at their busiest. The weather is at its most settled, although it is not unusual to see cloud build up late in the mornings and thunderstorms in the evenings. August is when most of the villages in the Zillertal hold their summer church festivals known as Kirchtags. They are extremely good fun, and it is well worth a visit to villages such as Stumm and Finkenberg, where the village will be set up with market stalls, street entertainment, local crafts and lots of music for a good day out, to be thoroughly enjoyed by all.

September announces the onset of autumn. The weather will be cooler and the huts quieter as they head towards the end of the season.

For a two-week holiday, the middle of July or the first two weeks in September are recommended.

Getting there

Getting to Austria is relatively straightforward no matter how you decide to travel. For the ZRR your first point of contact with the Zillertal valley is at the major road and railway intersection at the industrial town of Jenbach, in the Inn valley. Thereafter, the 50km (30-mile), 1hr journey up the Zillertal valley by road or rail leads to the resort town of Mayrhofen, the starting point of the ZRR (and the alternative start point for the ZSTT). Those undertaking the ZSTT need to head to Innsbruck, the provincial capital of Tyrol, before continuing by regional train to the small town of Steinach am Brenner, near the start point of the tour. (See Appendix C for a glossary of useful German–English travel words and phrases.)

By air (and rail)

Even if you travel by air, which is the quickest way to get to Austria and the Zillertal, for those undertaking the ZRR there is not always sufficient time to leave the United Kingdom in the early morning, catch a train to Jenbach and Mayrhofen, and then travel on to one of the huts before nightfall. It is better to stay overnight in Mayrhofen and then continue your journey the day after. However, if you are travelling light and have no hold-ups, it is just about possible to get to the Edel Hut by early evening. Similarly, for those undertaking the ZSTT it is better to stay overnight in Innsbruck or Steinach am Brenner.

Munich is the main entry point (from London, Manchester, Birmingham), but flights also go to Salzburg and Innsbruck (from London). Some of the major operators, particularly Lufthansa, have several flights a day from London, Manchester and Birmingham. Other budget carriers also operate from Luton, Gatwick and Stansted. (See Appendix B for airline websites.)

Although travelling by air gets you to mainland Europe quickly, you may lose precious time transferring to the railway station, the Hauptbahnhof, and may experience frustrating delays and hold-ups just finding your way about.

At Munich, the airport connects direct with the regional railway network, where there are frequent trains every 30mins or so. Follow the train signs DB and S. You need a pre-paid ticket before getting on the train. Do not push your luck without a ticket, as the Germans do not take kindly to freeloaders no matter where they come from. Be warned. There is a railway booking office in the airport arrivals hall adjacent to the concession counters for car hire, hotel reservations and so on. This facility is not always open, but if it is get your ticket to Jenbach hin und zuruck (there and back) if you are coming back the same way. There are frequent express trains every 2hrs or so. Once on your journey, get off the regional train at Munchen Ost (Munich East), listen to the announcements, and change platforms to get on one of the inter-city trains (schnell zug). Look out for the matrix sign boards at the station and on the side of the train, and get on the first one that has Innsbruck on it or Brennero, Venezia or Venedig – anything heading into Italy or Switzerland will do, as they all have to go via Jenbach.

If the ticket office is closed at Munich airport you can get your ticket at Munich East – the ticket office is at road level with other shops and fast food outlets. With express trains it is also possible to pay on the train, sometimes at a premium, if you can show that you had to rush and didn’t have enough time to get to the ticket office.

Railway tickets may also be purchased in advance and online by visiting www.bahn.de. There is a thumbnail Union Flag icon for English speakers to click.

At Jenbach, there is a local bus service and a narrow-gauge railway to the roadhead at Mayrhofen. This journey takes about 1hr. The last train to Mayrhofen is at 19.44, and the last bus at 21.08.

Mayrhofen Bahnhof railway station, with Dampfzug Puffing Billy train and the Ahorn Spitze on the left-hand skyline

Jenbach is the home of the Zillertal railway and its collection of old steam locomotives, known as the Dampfzug. But, more famed as Thomas the Tank Engine or simply Puffing Billy, these charming little trains are every kid’s delight. One of these little trains travels up and down the Zillertal valley throughout the season, pulling behind it 100-year-old bright red carriages. If you have children with you, the Dampfzug is a fitting way to start or end your journey in the Zillertal. There are only two Dampfzug trains per day, and many of the seats are reserved in advance, so plan your journey well (Jenbach/Mayrhofen 10.32/15.16; Mayrhofen/Jenbach 13.06/17.06).

At Salzburg, take Line 2 bus service from the airport to the Hauptbahnhof, from where a rail ticket can be purchased to Jenbach or Innsbruck. Journey time is just over 1hr, travelling west along the Inn valley.

At Innsbruck, from the airport there are a bus service and taxis to Innsbruck city centre and the Hauptbahnhof main railway station. Then take the regional train service to Jenbach or Steinach am Brenner.

By rail

Consult with Eurostar, but the two most commonly used routes are as follows. Each route gets travellers to Innsbruck and Jenbach within 18hrs of leaving London.

London–Dover–Calais–Paris–Zurich–Innsbruck–Jenbach

London–Dover–Ostend–Brussels–Munich–Jenbach

Check these websites for further details.

German Railways DB (Deutsche Bundesbahn), www.bahn.de

Austrian Railways OBB (Osterreichische Bundesbahnen), www.oebb.at

Verkehrsverbund Tirol, www.vvt.at

Post bus, www.postbus.at

Zillertal railway, www.zillertalbahn.at

By road

The most direct route by road is via the Dover–Ostend channel crossing, then by the motorway system to Munich and into Austria at Kufstein, followed by the short drive up the Inn valley to Jenbach and Mayrhofen. An alternative route goes from Dover by Lille to Luxembourg, then to Saarbrucken, Pirmasens, Bad Bergzabern, Karlsruhl, Stuttgart, Munich, Kufstein, Jenbach and Mayrhofen.

With more than one driver it is just about possible to get to Mayrhofen within 24hrs from Calais or Ostend. Whatever your chosen route, consult with your motoring organisation before setting out.

It is also important, when parking your car, to consider the return journey and getting back to it, as this is not always easy if you are forced to drop down into another valley (more likely on the ZSTT). It may be best to leave your car in Innsbruck or Jenbach, or one of the other major villages that has good bus or railway connections to and from Mayrhofen.

The following motor organisation websites provide useful information – www.adac.de and www.oeamfc.at.

Getting back

For those travelling by air, the last day of your vacation needs to be devoted to making the journey home. The journey time from Mayrhofen to Munich airport is around 2½hrs, to Salzburg 2hr, and to Innsbruck 2hr.

The first train from Mayrhofen to Jenbach is at 06.30, then there are services roughly every ½hr from 06.50 onwards.

The earliest train from Jenbach to Munich is at 08.07, with services at 09.02 and 10.57. Remember to change trains at Munchen Ost and get on the regional shuttle-train service S8 marked ‘Flughafen’.

From Jenbach the train times to Salzburg are roughly every two hours – 09.26, 10.02 and 11.26.

Accommodation in the valley

A typical street scene in Mayrhofen

There is no shortage of good places to stay in Mayrhofen and the Zillertal, as the whole district is geared to tourism and catering for visitors.

Hotels

In Mayrhofen, the main centre of the Zillertal, hotels tend to cater for the tourist trade, and accommodation is more expensive here than in the surrounding villages, but there is an abundance of guest houses and small hotels in the area where climbers and walkers may feel more at home. If you are not bothered about nightlife, then there are good bargains in the villages of Fugen, Kaltenbach, Zell am Ziller and Ramsau. The Hotel Poste in Jenbach, and the same in Kaltenbach, is recommended. Anyone booking hut accommodation over the internet will find that many huts have family connections with guest houses and hotels in the valley, and they will be happy to make recommendations.

For those wishing to stay in Mayrhofen, the Siegelerhof Gastehof, opposite the conference centre and main Tourist Information Office, is within 5mins walk of the railway station. It is managed by the Hausberger family, who provide good, clean, inexpensive bed and breakfast accommodation (tel 0043 5285 62493 or 62424, email siegelerhof@tirol.com, www.hotel-siegelerhof.at).

For accommodation in Steinach am Brenner (for the ZSTT) and Salzburg, see Appendix B. Should you need to stay in Innsbruck, hotels can be booked from the tourist information centre at the railway station located on the lower ground floor of the ticket hall (see Appendix B for recommended places to stay in the area).

Campsites

Those with a car will find good sites on the outskirts of Mayrhofen (camping Kroell, tel 0043 5285 62580), at Schlitters, Kaltenbach (camping Hochzillertal, tel 0043 6507 333398), Zell am Ziller (camping Hoffer, tel 0043 5282 2248) and Laubichl. See www.camping@alpenparadies.com. Groups intending to camp should enquire from the campsite warden about reduced fees while they are away. This is referred to as leeres zelt.

Youth hostels

There is no youth hostel (Verein Volkshaus) in Mayrhofen. The nearest hostel is in Innsbruck, located some 15mins walk on the northern site of the River Inn (email jgh.volkshaus-ibk@aon.at, www.jgh.volkshaus-ibk.at; see Appendix B for more details).

The Zillertal valley and Mayrhofen

From its entrance at Strass to its head at Mayrhofen, the 50km Zillertal valley is everything Tyrolean, with pretty chalet-style houses and organised charm. To the east the valley is bounded by the Kitzbuehler Alpen, while to the west are the lesser peaks of the Tuxer Alpen. Further up the valley lie the charming villages of Schlitters, Fugen-Hart, Kaltenbach-Stumm, Zell am Ziller, Hippach-Ramsau and lastly Mayrhofen – the Zillertal’s main village-cum-town and commercial centre, with the main peaks of the Zillertal mountains at its head.

The delightful town of Mayrhofen is one of the main holiday resorts in the Tyrol, wholly geared up for summer and winter tourism to suit all tastes and budgets. However, development came late to Mayrhofen, as it is located some 50km up a dead-end valley in the middle of nowhere, isolated from the main communication links of the Inn valley. While the Romans showed interest, and various wandering tribes came and went, the problems of access for trade always made it difficult for settlements to establish themselves in the valley.

Named after a few farms at the head of the valley, Mayrhofen started to feature in rural affairs at the start of the 18th century, mainly in relation to farming and as a good place to hunt and collect minerals. This isolation was no defence during the Napolenic wars of 1809, and the Zillertal menfolk picked up their arms and opted to fight for Tyrolean independence against the French and Bavarians with the folklore hero Andreas Hofer. Sadly this fight was lost and resulted in the Tyrol being ruled by the Bavarians for the next few years. By 1816 Napoleon had been defeated. The Tyrol was handed back to its rightful owners, with all the provinces united under the Royal Household of Emperor Franz Joseph I.

With the war over, almost another 50 years would pass before tourism and mountain wandering became part of the local economy with the establishment of the Austrian Alpine Club (OeAV) in 1862 and the opening of the Berliner Hut in 1879. Construction of the railway in 1902, which was built initially to support forestry and the transportation of minerals and magnesite ore from the lucrative mines of Hintertux, opened up the Zillertal valley immensely. Since then Mayrhofen has grown steadily through the wealth created by the Zillertal valley from agriculture, farming and forestry – but above all through tourism.

Activities for poor weather days

Mayrhofen, and the Zillertal in general, can be a rather miserable place should you be unfortunate enough to have indifferent weather, for the clouds just swirl around and refuse to budge from the peaks. Local lore has it that if the Ahorn Sptize has a raised hat, the weather will be good; if the hat is pulled down over his ears, the weather will be bad!

To help keep you entertained, particularly if you have children with you, here are some suggestions for what to do (other than the normal theme park activities) in poor weather.

Rattenberg This small, delightful medieval town with timber-framed quirky buildings and cobbled streets is famous for handmade glass. Take the train to Jenbach then the local bus service to Brixlegg and Rattenberg.

Schwaz (medieval silver mine) Take the train to Jenbach, then the regional train heading to Innsbruck, and get off at Schwaz; thereafter it’s a short walk to the visitor centre (see www.silberbergwerk.at).

Zillerbach River (white-water rafting) Great in the rain when the Zillerbach river is in flood; reservation offices in Mayrhofen.

Klettersteige It needs to be dry, but anyone armed with climbing tackle may find some consolation in indifferent weather by trying the Klettersteige (via ferrata-type protected climbing routes) that start near Gasthof Zillertal, not far from Mayrhofen railway station on the west side of the river.

Innsbruck Capital city of the province of Tyrol, named after the river on which it stands, overlooked by the Karwendel group of mountains and made famous as a centre for winter Olympics sports. The city is well worth a visit in its own right – particularly for the Old City (Alte Stadt), but also for the OeAV Alpenvereins Museum (open Monday to Saturday during normal business hours). Located within the Hofburg Imperial Palace in the Old Town, it has many fine exhibits from alpinism’s golden era, perhaps the most notable being memorabilia of Hermann Buehl’s ascent of Nanga Parbat in the Karakoram mountains of Pakistan.

Take the train to Jenbach followed by the regional train to Innsbruck. It is a 10min walk from the railway station (Hauptbahnhof) to the Old City.

Out and about in Mayrhofen

Mayrhofen Haupt Strasse (high street)

See the street map (above) for the location of the railway and bus station, tourist information office and post office. Useful websites include www.mayrhofen.at and www.zillertal.at.

Bus services

The following times are for the local post bus service that leaves from Mayrhofen’s combined train and bus station.

Mayrhofen to Ginzling/Breitlahner/Schlegeis

06.40/07.55/09.25/11.25/13.25/15.25/16.55/17.55

Schlegeis to Mayrhofen

09.35/10.35/13.55/15.35/16.35/17.55

Breitlahner to Mayrhofen

09.55/10.55/14.15/15.55/16.35/18.15

Ginzling to Mayrhofen

10.10/11.10/14.30/16.10/17.10/18.30

Tourist offices

The main Tourist Information Office and conference centre, the Europahaus, is located near the railway station on Durster Strasse. There are also satellite tourist offices in the town (see Appendix B for full contact details).

Post office and mail

The post office in Mayrhofen is located just off the main street in the centre of town (see street map, above), and has fax, internet and money-exchange facilities. The post office is open Monday to Friday from 08.00 to 12.00, then 14.00 to 18.00.

At huts postcards can be purchased and mailed from the hut’s post box. The mail is then taken down to the valley, usually once a week and deposited at the main post office. Not surprisingly, post to UK can take 10–20 days.

Places to leave luggage

There is a left-luggage facility at the combined bus and railway station, which is open Monday to Saturday 08.00 to 18.00. Alternatively, should you be staying at one of the hotels, most hoteliers are quite happy to store luggage until you return.

Peter Habeler’s office (mountain guides)

The services of a professional mountain guide can be hired via Peter Habeler’s office on Mayrhofen’s main high street (Haupt Strasse). See Appendix B for more information or contact www.bergfuehrer-zillertal.at.

Trekking with children

A family from London trekking in the Zillertal with children aged 12 and 8, still smiling!

How suitable is hut-to-hut touring for children? The Austrian Alpine Club actively encourages children to participate in mountain activities, and most children love visiting the various huts and the sense of freedom it gives them. Children need to be fit, but if they are capable of ascending Ben Nevis, Snowdon or the round of Helvellyn then they will surely enjoy some of these tours. The author’s daughter traversed the entire length of the ZRR and climbed several peaks along the way when she was 14 years old, and children as young as eight have undertaken the majority of the tour. However, the ZSTT is not really suitable for children under 15 years.

But only parents can decide, since some of the day’s outings are quite long, particularly the Greizer to Berliner Hut and Berliner Hut to Furtschagl Haus stages. Children must be happy to be in the mountains for long periods at a time and easily entertained in the evenings, reading books, playing scrabble or simply chatting. One good tip is to have a friend with them for company and it is important to make sure that they have adequate stops en route and rest days.

Health and fitness

While you do not have to be super-fit to undertake these tours, it is essential that participants are used to walking for 6hrs continuously while carrying a touring-size rucksack weighing in the region of 12–15kg.

Altitude

The average altitude encountered on the tour is around 2500m–3000m (8000ft–10,000ft), so people visiting the Zillertal do not usually suffer badly from altitude sickness. However, you may feel the effects of altitude – such as feeling out of breath, mild headache and slowed pace – particularly on the high peaks such as the Grosser Moseler and Olperer. The best defence against altitude is to be as fit as possible, eat and drink normally, and to get adequate rest and sleep.

Emergencies and mountain safety

The Siebenschneidenweg (‘seven ridges way’), as seen in profile from below the Lapen Scharte en route to the Greizer Hut (ZRR Stage 2)

Both the tours in this guide involve sustained activity in a mountain environment. Inevitably, this increases the risk of an accident taking place, such as a severe fall, a broken limb or some other serious mishap, which will all result in the mountain rescue team being called out.

One of the benefits of membership of the OeAV is mountain rescue insurance in case of accident. This can be supplemented from a specialist insurance company, details of which are available from the Austrian Alpine Club (UK) and the advertisement sections of one of the many climbing magazines. Similarly the British Mountaineering Council (BMC) has an excellent insurance policy, which can be obtained separately to membership.

The value of insurance should not be underestimated, as the cost of a mountain rescue can be considerable when helicopters, police and professional mountain guides are brought into use. Unlike in the United Kingdom, where mountain rescue services are generally provided free of charge by the local authority and mountain rescue teams run by enthusiastic volunteers, in the alpine regions most countries will charge the hapless victim. Be warned!

Mountain safety is as much about prevention as it is about cure, so check out all your gear, practise constructing your improvised rudimentary harness and the time-consuming tasks of putting on crampons/harnesses and roping up, and develop your glacier travel skills and crevasse rescue techniques before you go (see ‘Alpine walking skills’, below).

European Health Insurance Card (EHIC)

This card (previously form E111) is available free from any post office – just fill in the form to receive a credit-card-size EHIC identity card that entitles you to free medical care in any EU member state, including Austria. Should you be unfortunate enough to need medical attention while on holiday, then this card will help to pay your way. However, the EHIC entitles the holder only to those services provided free in the member state; it does not cover any aspect of medical repatriation. So even with an EHIC, you still need to be insured.

EMERGENCIES

Emergency services operate on a different satellite frequency to normal services, so the following numbers can be dialled from a mobile phone even when the phone indicates that there is no reception from your service provider. Fortunately, in Austria mobile phone reception is excellent.

Mountain Rescue (Bergrettung) Austria 140

Mountain Rescue (Bergrettung) Italy 118

Red Cross (Rotes Kreutz) 144

European emergency telephone number 112

International Alpine Distress Signal

Help required: signalled by shouting, blowing a whistle or flashing a torch at 10 second intervals for one minute. Then pause for one minute and repeat.

Answer received: signalled by shouting, a whistle or a flashing a torch at 20 second intervals. Then pause for one minute and repeat.

Signals to helicopters

Should you be involved with a helicopter rescue...

Stay at least 50m from the helicopter.

Do not approach the helicopter unless signalled by the winch man to do so.

Do not approach the helicopter from behind.

Ensure that all loose items of equipment are made secure.

The Austrian Alpine Club

Above Schwarzsee, with Turnerkamp (left) and the Grosser Moseler (centre) (ZRR Stage 4)

Huts throughout the Zillertal are administered by the Austrian and German Alpine Clubs, the OeAV and DAV respectively, except for those in the South Tyrol that are owned and administered by the Italian Alpine Club (CAI) or its regional equivalent, the Alpenverein Sudtyrol (AVS)

The Oesterreichischer Alpenverein (OeAV), translated as the Austrian Alpine Association, was founded in 1862 to foster and encourage the sport of mountaineering and is largely credited to Franz Senn, who was the village priest in Neustift (Stubai valley) until his untimely death, aged 52, from pneumonia, and his associates Johann Studl, a wealthy Prague business man, and Karl Hofmann, a young lawyer from Munich.

The Alpenverein, which celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2012, was the first alpine club to be established in mainland Europe. Presently the Club has just over 400,000 members in 195 Sektions that embrace all facets of mountaineering. Membership is open to any person who has a love of the mountains, regardless of age or ability.

The Club’s principal activities include the development and provision of mountain huts, marking and maintenance of footpaths, production of maps, organising of mountaineering courses, and action on environmental issues, particularly those which are seen to spoil the mountains by either physical or visual pollution.

The establishment of the United Kingdom section, OeAV Sektion Britannia, is largely credited to Major Walter Ingham and Henry Crowther. It was formed in 1948 just after the Second World War to foster Anglo-Austrian relationships and to make it easier for British mountaineers in the immediate post-war years to visit the Eastern Alps.

Presently OeAV Sektion Britannia is one of the largest UK mountaineering clubs, with over 8000 members. The Club has a regular programme of indoor and outdoor meets, together with a website (see www.aacuk.org.uk) and quarterly newsletter. The Club also runs training courses for its members, both in the UK and in Austria, through the Alpenverein Akademie mountaineering school. The Austrian Alpine Club (UK) enjoys full reciprocal rights agreements with all other alpine clubs in France (CAF), Switzerland (CAS), Italy (CAI) and Germany (DAV). This means that if you were to visit the South Tyrol in Italy to stay at the Schwarzenstein Hut, for example, you would pay the same fees as those enjoyed by members of the Italian Alpine Club and vice versa.

Anyone intending to undertake a hut-to-hut tour in Austria is strongly recommended to join OeAV Sektion Britannia (see Appendix B for full contact details).

Mountain huts

A smiling face awaits you at the end of your day’s walk

The word ‘hut’ is a misnomer. All the huts in the Zillertal as described here are more akin to mountain inns or guest houses that provide overnight accommodation and some form of restaurant service (see ‘Meals and menus’ below). This means that the mountain traveller does not need to return to the valley every few days to stock up on provisions.

There are well over 1000 huts in Austria, half of which are owned by the Austrian and German Alpine Clubs. In the Zillertal there are 30 OeAV and DAV huts, most of which are open from the end of June to mid-September. All the huts in the Zillertal have a resident guardian (Huettenwirt), who traditionally was a mountain guide (Bergfuehrer). Each hut has simple sleeping accommodation in the form of mixed dormitories (Matratzenlager) with blankets and pillows, and a small number of bedrooms (Bettzimmer) with duvets and sheets.

In addition to sleeping accommodation, each hut has some form of restaurant service offering a number of traditional dishes (see Appendix C for a glossary of menu terms). The menu generally comprises soup, a choice of main meals, Bergsteigeressen (literally ‘mountain climbers’ food’), cold meats, cheese and sometimes cakes and sweets. All huts serve drinks, tea, coffee, beer, wine and so forth, and most huts have a small shop where visitors can buy postcards, chocolate and biscuits.

On arrival at the hut, you should first remove your boots and store them in the boot rack, which will be close to the front door. You should also hang your ice axe, crampons, rope and other clobber on the racks provided, since such paraphernalia is not permitted in dormitories and bedrooms. If you are wet on arrival, your waterproofs should be shaken as dry as possible outside and hung up to dry with your ice tackle. If you are in a group, do not mill around the doorway, and again if you are wet make sure your group leaves outside as much water and dirt from boots as possible. Many of the huts are spotlessly clean, and for the benefit of all guests would like to remain that way.

You should then establish contact with the hut guardian to obtain your overnight accommodation. You will usually find this most important person in the kitchen (Kuche), dining room (Gaststube) or office (Bureau). A maximum of three nights is the Club rule, but this is not generally rigidly enforced. (Note that members have priority when accommodation is busy.)

Having found the guardian it is important to greet him or her (‘Gruss Gott’) and to explain that you would like some accommodation. The Huettenwirt is then likely to ask if you are Alpenverein and to ask for your membership card, which may be retained overnight or until such time as you leave, when you will be asked to pay.

If you do not speak German and feel uncomfortable asking for rooms in German, then write down and read out the following phrase ‘Ich/wir hatte gern ein zimmer oder matratzenlager, bitte’ (‘I/we would like a room, please’). Be polite by asking bitte when handing over the message and answering danke (‘thank you’) when the message is returned. Trivial as this may seem, these polite gestures are extremely important and will go a long way to ensuring a pleasant stay.

At the Olperer Hut – it doesn’t come much better than this!

If the hut is full you may have to take residence in the Winterraum, which is usually the preserve of ski-mountaineers and those visiting when the hut is closed. The Winterraum is generally an annexe to the hut and may double as a storeroom or shelter for animals (as is the case at the Greizer Hut). Although the Winterraum can be quite cosy, remember to keep your gear off the floor out of reach of any mice.

Should the hut be beyond full, you will be provided with a mattress for Notlager, which roughly translated means ‘sleeping with the furniture’ – be it on the floor, in the corridors, on tables, on benches, or simply anywhere you can lie down. In the Zillertal this is a rare scenario, which results in some cosy, if somewhat noisy, situations.

Only on very rare occasions will you be asked to move on by the Huettenwirt, but only when bed space has been secured at an adjacent hut and only when there is sufficient daylight for you to reach your destination.

At the hut you will also require a sheet sleeping bag or Schlafsack for use with the blankets and bedding which the hut provides. This is to minimise the amount of washing required and any water pollution downsteam of the hut. The sheet sleeping bag is a compulsory requirement, and if you do not have one the Huettenwirt will tell you to hire one.

You will also need to bring with you a pair of lightweight shoes or a pair of socks to wander around the hut, as boots upstairs are strictly forbidden (Verboten).

Each hut will have some form of male and female washrooms and toilet facilities, which vary from excellent at the Berliner and Olperer Huts to more modest at Friesenberg Haus and Greizer Huts. Elsewhere in the hut, usually near the front door, is the drying room (Trockenraum), where wet clothes can be dried.

The heart and soul of the hut is the dining room (Gaste Stube). Here you will find all manner of activities going on – from groups planning their next day, people celebrating a climb or a birthday, to people just chatting. It is a feeling best described by the German word ‘Gemutlichkeit’, which means ‘homely’ and ‘friendly’, and is something that is fostered and cherished throughout the whole of Austria.

At the end of your stay remember to make your bed and fold your blankets, to look around to make sure nothing is forgotten, and to search out the Huettenwirt and thank him and his staff for a pleasant stay. Remember to collect your membership card if it has not been given back to you. You should then fill in the hut book to record your stay and to indicate where you are going next.

Hut information and reservations

At Friesenberg Haus (ZRR Stage 7)

As more and more huts in the Zillertal develop websites and are accessible by email, it is easier than ever to check for up-to-date hut information and make a reservation (see the Hut Directory, at the end of this guide, and Appendix B for contact details). For small groups of three or four people it is not necessary to make a reservation at the huts. However, groups of six plus are strongly advised to make contact with the hut before they go by post (sending a prepaid stamped addressed envelope for a reply), telephone, email or the hut website.

It is worth noting that members are allowed only three consecutive nights at any one hut, although this is not strictly enforced.

Cancellations

Because huts can be booked over the internet and by telephone, abuse of this facility is beginning to become an issue. When reservations are made and people do not turn up, this results not just in a loss of business for the huts but also in a significant waste of food. Some huts are now asking for deposits to offset some of this risk. It is worth noting that in Austrian law if you make a reservation and do not allow adequate time for a cancellation then you are still liable to pay the bill in full or in part. Remember that most huts are businesses, and it is only polite, if you have to cancel your reservation, to make every effort to contact the hut to inform them. If not, don’t be surprised if you get billed.

Meals and menus

All huts have some sort of restaurant service to cover the three daily meals, breakfast (Fruehstuck), lunch (Mittagessen) and dinner (Abendessen).

Breakfast is served from about 06.00 to about 07.30. Thereafter no meals are available until lunchtime as the hut staff are busy with general house-keeping. Breakfast is the meal generally regarded as the worst value for money – but unless you are carrying your own provisions you will have little choice other than to accept it.

Lunchtime is usually from 12.00 to 14.00, but varies depending on the hut. However, it is possible to purchase simple meals like soup, Kase Brot and Apfelstrudl at most of the huts throughout the afternoon.

Dinner is the main meal of the day and is generally served from 18.00 to 19.30. In addition to meals listed on the menu, Bergsteigeressen will be available. Literally translated it means ‘mountain climbers’ food’, and is a low-priced meal containing a minimum of 500 calories. The meal generally comprises spaghetti or pasta, potatoes, some meat or sausage, and sometimes a fried egg or a dumpling. There is no hard-and-fast rule to this meal – other than it is relatively inexpensive and that there is usually a lot of it!

Breakfast usually comprises two or three slices of bread, a portion of butter, jam and cheese, with a choice of tea or coffee. If you do not finish it, take it with you – as you have paid for it all! Lunch and dinner are the main meals of the day and are served with a selection of vegetables or salad, and there will be vegetarian (Vegetarische) options. Drinks are served in quarter (Viertel) or half (Halbe) litres, or large (Gross) or small (Klein), and maybe hot (Heiss) or cold (Kalt). Tea, coffee, hot chocolate, lemonade, cola, beer, wine and schnapps are all available at the huts. See Appendix C, which lists many items found on a typical hut menu (Speisekarte), as well as some useful words and phrases for reading menus or ordering food and drink.

Generally the procedure for ordering meals is that you first organise a table. There is no formality, but sometimes when mountaineering training courses are being run, groups of tables may be marked ‘private’ (Privat) or ‘reserved’ (Reservierung). Having sat down, one of the waitresses (Fraulein) will take your order. Alternatively, you may have to go to the counter or kitchen (Kuche) to order, or there may be a sign saying ‘Selbsbedienungs’ (‘self-service’).

Because of the excellent service the huts provide very little of one’s own food needs to be carried. However, many people do take with them their own basic rations – tea, coffee, bread, cheese, and so on. This allows them to make their own snacks and, by borrowing cups and purchasing eine litre teewasser, allows them to brew up for a small cost.

The only facility not provided at huts is for self-catering, and it does seem a little pointless when all the meals are reasonably priced.

The general rule is to pay an accumulative bill for food and drink. Visitors are therefore advised to make notes of their consumption to aid checking at the time of payment. Take note, these bills/lists can be considerable when staying at a hut for more than a couple of nights.

As a guideline for working out a budget, typical meal price lists can be obtained from the UK Section of the Austrian Alpine Club (www.aacuk.org.uk). At the time of writing, the cost of dinner in a hut was similar to prices in most British pubs for a decent bar meal plus drinks. Half board is currently €35–40, depending on the category of the hut.

Maps and guidebooks

The following maps are required for both tours in this guide. The maps are published by the Austrian Alpine Club and available from the UK Section of the Austrian Alpine Club (www.aacuk.org.uk).

Maps

| Alpenvereinskarte Zillertal Alpen | ||

| Sheet 35/1 | Westliches (West) | scale 1:25,000 |

| Sheet 35/2 | Mittler (Central) | scale 1:25,000 |

Also recommended, covering the complete region at a glance and available from major map retailers, are

Freytag & Berndt Wanderkarte: Sheet 152, scale 1:50,000, Mayrhofen, Zillertal Alpen, Gerlos-Krimml

Kompass Wanderkarte: Sheet 37, scale 1:50,000, Zillertaler Alpen; Tuxer Alpen

Books

For guidebooks and other reading see Appendix D.

Websites

These are currently in German but they will inevitably at some stage be translated into English.

www.zillertal.at

www.berlinerhoehenweg.at

Alpine walking skills and equipment

On the Schwarzensteinkees glacier at the Schwarzensteinsattel (ZSTT Stage 7), with Gross Moerchner to the right (note the knotted rope)

How do the skills and equipment needed for walking in the Zillertal differ from those required for elsewhere?

Boots

A relatively stiff boot with good ankle support and a stout vibram-type rubber sole is essential. Many of the walks involve sustained hard walking over rocky slopes and glacial debris, and encounters with patches of old hard snow. It is important to think of your boots as tools that can be used to kick steps and jam into rocky cracks without causing damage to your feet. While bendy boots may be a bit lighter and more comfortable, they are no match for a good pair of four-season mountaineering boots when it comes to dealing with difficult ground.

Alpine walking equipment

Instep crampons or microspikes

While crampons are normally associated with climbing, a pair of these little tools often comes in very handy when the weather decides to dump some unseasonable snow in July or August, and they may just help provide that little extra security when you get up close to some old hard-packed snow.

Improvised harness

Many of the routes are equipped with fixed wire ropes to provide some support over bits of difficult terrain. While these may be relatively easy to cross, the consequences of a fall should be borne in mind. In addition, not everyone is vertigo free, and the use of an improvised harness helps to provide confidence and security of passage. Constructed from a 2.4m long by 10mm wide Dyneema sling, three or four overhand knots, and a large jumbo-sized screw-gate karabiner, this harness (pictured) will allow you to clip into those fixed wires whenever the need arises and arrest a fall when you least expect it.

Construction of a rudimentary harness

Trekking poles

Poles are almost standard accessories for most people these days, but in the Alps they come into their own – being very handy when crossing glacial steams and for traversing steep patches of old snow.

Glacier travel

The glaciers of the Zillertal are in the heartland of the Tyrol and the Eastern Alps. Quite a few of the mountaineering routes (‘Excursions’) described in this guide involve crossing or negotiating glaciers that can be crevassed depending on the time of year and vary from season to season. Indeed the ascent of the Grosser Loeffler (ZRR Excursion 3.1) is classed as the most crevassed climb in the Zillertal.

Although crevasses (Spalten) will be encountered they should not create a serious problem for the mountain traveller and most will be easily bypassed. As is common to most glaciers, the main crevasse zone is on the steep sections, at the edges, and where the ice breaks away from the underlying rocks to form bergschrunds (Randkluft). If difficulties do arise it will be in negotiating bergschrunds such as those that exist below the Grosser Loeffler on the Floiten Kees glacier.

In the route description orientation on the glacier is described as being in the direction of flow along the right- or left-hand bank. This means that in ascent the left bank will be on your right. To avoid confusion, as may happen when route finding in mist, a compass bearing has been added in the route description to aid direction.

While most of the Zillertal’s glaciers are relatively straightforward, they can vary quite considerably from season to season, the Floiten Kees and Schlegeis Kees glaciers being good examples. This scenario is further exacerbated by large temperature variations, generally because of the glaciers’ relatively low altitude. This means that while routes may be straightforward one year, with minimal snowfall in the following year, previously hidden crevasses may become exposed and enlarged. The result is that glacier travel becomes more problematic.

It’s better to practise this on safe ground before you go, rather than having to ‘practise’ in a real-life situation

The ideal number of people for glacier travel is four. Two is the absolute minimum, and solo travel should be avoided for obvious reasons. A party of two could gain some extra security by teaming up with a second party, gaining strength through weight of numbers.

Many of the Zillertal’s glaciers are dry glaciers at their lower levels and are quite safe to traverse unroped, as the crevasses are obvious and easily avoided. However, when crevasses pose a threat – for example where they overlap, are deep, and occur on steep ground, as is found on the Grosser Loeffler – then the party should be roped up. Equally, parties should be roped at all times while crossing glaciers that are snow covered, such as those on the Schwarzenstein Kees glacier on the approach to the Berliner Hut, no matter how well trodden the route. It is worth remembering that crevasses have no respect for people and can open up beneath the best of us.

For a roped party of three, the group leader (the most experienced person) is best placed in the middle, since it is the group leader who will contribute most to a rescue in the event of a mishap. The second most experienced person should take the lead position at the head of the rope in order to route find and the last person, preferably the heaviest, should take a place at the back to act as the anchor.

For parties visiting the Alps for the first time, particularly those of equal ability, some experimenting will be necessary to gain more experience. However, it is absolutely essential that you practise roping up and crevasse rescue before you go, particularly a crevasse rescue scenario in which the fallen climber is out of sight of his companions and another member of the party has to go to their assistance and enter the crevasse, as would be the case if your companion were hurt.

A tried and tested crevasse rescue technique

The following technique is suggested (only ‘suggested’ because the style varies between German- and French-speaking parts of the Alps). If you learned glacier and crevasse techniques in the Western Alps you may well have been taught a different but equally valid approach. This method works and will ensure that a group has a safe anchor at all times.

In ascent and descent the lightest person should go first at the front to route find. Should the route finder fall into a crevasse (unlikely) it is improbable that the rest of the group will be dragged in after them, but in a full-on fall you will be dragged off your feet. In case such a mishap occurs then the heaviest person is best placed at the back to act as the anchor. For a party of two the most experienced person should be at the back in both ascent and descent.

To rope up a party of three, the middle man (group leader) should tie on 15m from one end of the rope, with the rope leader tied on at the front end. The back man (anchor) should then tie on about 12m behind the middle man (group leader). The surplus rope at the end should then be coiled by the anchorman and carried over the shoulder and rucksack or, as the author prefers, it can be loosely coiled inside the top of the rucksack, from where it can be easily retrieved in the event of being needed for a crevasse rescue. In addition to roping up, two Prusik loops are needed for attaching to the rope by each person, to be stored in their pockets.

On most glaciers the party will move together, keeping a respectable distance between each person. When there is no crevasse danger a few rope coils may be carried in the hand of each person to make the rope more manageable and to help prevent it snagging and being dragged along the glacier’s surface, making the rope wet and heavy.

When crevasse zones are encountered, the rope between individuals should be kept taut to limit the effect of a fall. Where crevasses pose a very real risk, such as when they are large or their extent is unknown, the rope leader’s second (middle man) should belay, while the rope leader traverses or jumps the crevasse. At the same time the group’s anchorman will be similarly belayed a safe distance away. While these procedures may seem complicated and time-consuming, with a little practice they should become second nature.

The purpose behind these techniques is to prevent climbers falling into crevasses and to ensure glaciers are crossed safely. Most mountaineers will spend many hours crossing glaciers without any serious mishap. Experienced mountaineers will be able to recall falling into crevasses up to the waist, a few to the chest and the odd one falling through the surface to the glacier below. In most instances during a fall climbers can react quickly enough to spread their weight by outstretching their arms or by falling backwards to prevent themselves falling further. Once the fall is arrested, the group’s second (the group leader) should belay while the anchorman uses their weight and position to secure the belay, which then frees the group leader to make use of the anchorman’s coiled spare rope to effect the rescue and haul the leader free.

Should the leader fall free and end up inside the crevasse, it is important that the rest of the party work quickly. If the leader has fallen into a concealed crevasse it is likely that they will be hurt. This is due to the fact that their rucksack will have jarred, pushing the head forward and banging it on the ice during the fall. In such situations there are a number of options to choose from, but all will be useless unless the group has spent a little time practising crevasse rescue techniques. This is absolutely essential.

In this situation, provided the rope leader is uninjured, it may be possible to:

simply haul them out of the crevasse using brute force

help the rope leader to Prusik out of the crevasse under their own steam

by lowering the end of the surplus rope, rescue the rope leader by using a combination of hauling and Prusiking using the Assisted Hoist Rope Pulley method (see diagram).

If the rope leader is injured, then the actual group leader will have to go into the crevasse to perform first aid and secure the second haulage rope. Thereafter, once the group leader (the middle man if there are three of you) is back on the surface it is just about possible for the group leader and anchorman to haul the rope leader to the surface, using the Prusik loops to lock off the hauling rope. In this scenario a full-blown mountain rescue is perhaps the correct decision.

The UK Section of the Austrian Alpine Club organises basic training for glacier crossing and crevasse rescue through the OeAV Alpenverein Akademie. Contact the AAC (UK) Office for details, www.aacuk.org.uk.