Читать книгу Ginza Go, Papa-san - Allan R. Bosworth - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDriving Is

Justa Rittle

Different

THE red English sports car at the head of the line, waiting to buzz down the Tokaido—Japanese Route Number One Highway—bore a stranger device than anybody realized. Painted across the cover of its spare wheel was the word "HARE."

To you and me that is a reminder that the race is not always to the swift, a proverb especially applicable to sports-car rallies in a land where the speed limit is thirty-five miles an hour. But to the small Japanese girl who sat beside me as my guido, the label was only confusing.

"Papa-san?"

"Yes, Richi-san?"

"Papa-san, what meaning 'har-reh,' Engrish speaking?"

"Har-reh?" I puzzled, and then, when she pointed to the sign, "Oh, I see. That means rabbit—usagi. That car is usagi, and all these others, including ours, are inu. Rabbit and dogs—hare and hounds. Understand?"

She shook her head. "I don' sink usagi, Papa-san. I don' understand. Japanese speaking har-reh meaning justa rittle stomachy, and nice wezzer. I don' know!"

"I don't know, too," I muttered. The starter was about to give us the flag, but you can't start out on any kind of enterprise with such incongruities as justa rittle stomachy and nice wezzer left hanging in the air. I reached for the dictionary.

Sure enough, haré means "a stomach tumor," and a word spelled exactly the same means "clearing weather."

"You win," I told Richi-san. "Why have you people mixed up the language like this—haré and haré? I'll never learn Japanese! Japanese is taihen muzukashii— very difficult!"

"Engrish easy, Papa-san?"

"Of course, English is easy. Hare—we pronounce it hare, not har-reh. Same as the hair on your head—kami. However, it means usagi.

"Thirty seconds!" yelled the starter, meaning us. "Twenty... ten... five ... Go!"

We went—one of twenty-odd sports cars popped at timed intervals into the stream of traffic—to watch for special signs along the road indicating where numbered clues were hidden; to attempt to overtake the usagi, if we could; and to wind up about noon somewhere in the vicinity of beautiful Lake Hakone—where neither of us had ever been. Three blocks farther on, in a welter of bleating takushi-cab horns, Richi-san looked up at me and made the understatement of the year:

"Engrish anda Japanese, Papa-san, justa rittle different!"

Driving an automobile in Japan is justa rittle different, too, if you ask Papa-san. Driving in Japan will give you stomach ulcers, if not even a sizeable haré, or tumor. A day at the wheel leaves you weary, dusty, bewildered, and certain of only one thing—Japan is an ancient country, and its roads were here a long time before the automobile was invented. Japan will still be here, too, a long time after the last jidosha has rusted. That is, unless the Tokyo takushi-cab driver, who is the original Young Man With a Horn, blows it off the map.

It is true that some small improvement has been made in recent months, but only a year ago experts called Tokyo the world's noisiest city, and I doubt that it has lost the championship title. Factories do not create this pandemonium; they are mostly small, and the larger ones are located in outlying districts. Trains and streetcars contribute only a small share, although some of them are equipped with bugle-like horns operated by compressed air and can make the kami rise on the back of your neck at a distance of a quarter-mile when they let go a blast. Much of Tokyo's working population is whisked back and forth by subways, and the subways are not heard above ground.

It is true that during election campaigns hundreds of sound trucks shriek hysterical promises of a chicken in every nabé, and throughout every business day loudspeakers on any corner extol the virtues of products ranging from soap to TV sets. The geta's clack and the chindonya —a one-man band—plays bells and drum and samisen to advertise a new restaurant, or the bill at the corner movie theater. Rut day-in and night-out most of the bedlam can be blamed on Tokyo's thousands and thousands of small, scurrying, pomade-scented takushi-cabs.

Back in 1933 the following "Rules of the Road" were posted in Tokyo's Central Police Station, and it is reasonable to assume that the same chauffeurs' catechism was promulgated in Japanese:

1. At the rise of the hand policeman, stop rapidly.

2. Do not pass him by or otherwise disrespect him.

3. When a passenger of the foot heave in sight, tootle the horn. Trumpet at him. Melodiously at first, but if he still obstacles your passage, tootle him with vigour, express by word of mouth the warning "Hi, Hi."

4. Beware the wandering horse that he shall not take fright as you pass him by. Do not explode the exhaust box at him. Go soothingly by.

5. Give big space to the festive dog that shall sport in the roadway.

6. Go soothingly in the grease mud, as there lurks the skid demon.

7. Avoid tanglement of dog with your wheel spokes.

8. Press the braking of the foot as you roll round the corner, to save collapse and tie up.

The Japanese were ever remarkably obedient to the law of the land. They are still tootling, with vigour. Tokyo is, without doubt, the tootlingest town in the world, and the practice has spread into Yokohama, Osaka, Sendai, Yokosuka, and Tachikawa, as well as into the more remote prefectures. Not only have the Japanese developed tootling into a fine art, but their mechanical skills have not been idle, and horns stamped "Made in Japan" can make a Detroit tootle sound like a confidential whisper.

A little of this frays the nerves of foreigners, who are more inclined to be high-strung than the Japanese. Especially did the din offend the auditory senses of the British, and some of them wrote long letters to the editor of the Nippon Times, complaining of the "excessive horning."

Papa-san's own reaction to the cacophony varies, depending on whether he is afoot or awheel. As a pedestrian, crossing a narrow, teeming street in Shimbashi amidst a babel of raucous, ear-splitting blasts, which appear to serve no useful purpose, the impulse is to flee up the nearest alley like a scared usagi and take refuge in some little four-mat restaurant that serves Chinese noodles. Behind the wheel of a car on which ¥6000 road tax has been paid, Papa-san has what is probably an average American urge—a strong desire to get out of the car and poke a cab driver in the puss. But he doesn't. After all, we are all goodwill ambassadors in this, a sovereign country, and what is more, somewhere an MP is always lurking, like the skid demon in the grease mud....

There has been some improvement in the noise situation, yes. But it will not get much better, and the general traffic problem would appear virtually insurmountable. Japan is a crowded country by either metropolitan or rural standards; and although Tokyo has many broad streets, you have only to turn a short distance from them to find yourself squeezed between narrowing, medieval walls, on a way that is hopelessly winding. There is barely room for the present traffic, and yet motor cars, like the population, are on the increase. The last figures available were for 1952, when there were 652,000 vehicles of all kinds registered in Japan. If you have driven a car in this country, you will not be surprised to learn that 320,000 of these were trucks—and I would estimate that 319,000 of them were driven by people addicted to a middle-of-the-road philosophy. In addition there were 22,000 buses, and I estimate that 21,364 of these were Diesel powered and gave off huge clouds of black smoke in the faces of those who had to follow because there was not room to pass.

About 39,000 automobiles belonged to us, the foreigners, and that left some 74,000 privately-owned cars for the Japanese. It will shock anyone who has driven in Tokyo to learn that there were only some 23,812 taxis—I, myself, have encountered at least 22,009 of these on a single drive down the Ginza.

Incidentally, it is interesting to compare the ratio of privately owned jidosha in Japan to that of other countries. There is one car for every four persons in the United States, and one for every twenty in the United Kingdom. But in Japan the ratio to the total population is only one car to every two thousand people. Japan manufactures more trucks, however, than Italy does. I suppose that figure includes the pack of small three-wheel jobs you meet at every turn—when you are going straight....

Stick your neck out—literally, if you are around six feet—and ride in one of the smaller ¥70 or ¥80 cabs. Signal from the curb by waving, as if you were waving goodbye—in Japan, that means "come here." Or merely appear on the curb. The takushi is an extremely mobile vehicle, and will veer from the middle lane of traffic on short notice or none at all, throwing half a block into confusion. Look in your conversation dictionary, speak the address, and then say, "Kono tokoro e imitai desu, o-negai," and you're off like a bat out of hell.

What you have just said, literally, is, "This place to, wish to go is, if you please." Don't brood about that, however, and don't look out the window unless you have a strong heart. The driver is proceeding on his embattled way, along the hidari side rather than the migi. He passes jam-packed, snorting, smoking buses, most of them bearing the warning THEN PROCEED WITH CAUTION, without advising what to do before THEN. He leans fondly on the horn, scatters a crowd patiently waiting to board a streetcar, breaks into an open stretch, and pushes the accelerator to the floor.

All hell has broken loose. Papa-san has to depend on the conversation dictionary, which is hard to read at such jiggling speed, but which contains a phrase that means "So much don't run!" You will be thankful when you can order, "That corner at stop." The ¥70 and Y80 cabs are cheap transportation, and not worth it.

Japan will have to do something about its traffic, if not about the tootling. The toll of deaths and injuries on Japanese roads in 1952 appears low, at first glance, in a country of eighty million population—4,696 dead and 43,234 injured. But this was an alarming increase of 41.2 percent over the figures for 1951, and on the basis of the total number of vehicles, it means that one out of every 138 vehicles has killed somebody. If we had a comparable death toll in America, which had more than forty-two million cars that same year, we should have killed off more than three hundred thousand persons on the highways.

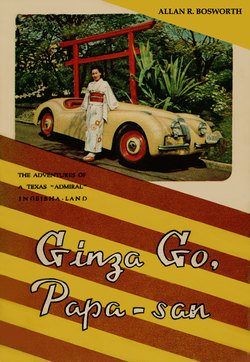

But motoring in Japan can be takusan fun, and it is the best way to see the real country, away from downtown Tokyo. Road signs are bewildering, road maps scarce, and you should learn to convert kilometers into miles. As I have said before, you need a guido. Come back now with Papa-san, rolling down the Tokaido with what Richi-san calls the Su-ports Car Crub. The membership of this group is very cosmopolitan, and the same could be said of its membership card. The latter shows a torii gate, emblematic of Japan; it bears English text; and at the bottom, with a fine cosmopolitan flair, is printed: "Pour le Grand Sport."

We are now beyond Yokohama, and there are stretches of green countryside, colorful villages, rice paddies, and chuckholes in the pavement a foot deep. It is very nice wezzer, indeed, the kind of wezzer that brings Japanese out for "cherry-viewing," "moon-viewing," or a plain American-style pikunikku. It is top-down weather.

"Papa-san?"

"Yes, Richi-san?"

"Don' put on cover?"

She is asking if I am not going to put up the top. I say no, I wouldn't be caught dead with the top up on a day like this, and ask her if she is cold.

"Not cold, Papa-san. But hair bu-roke."

I tell Richi-san that a wind-blown bob is quite fashionable in the States, although I really don't know, because I've been away from there quite awhile now. And everybody knows how women's styles are—all time changee-changee.

"Papa-san, today morning I'm forget some'sing, ever'-sing. Ba-ad head, don' you?"

Richi-san never asks, "Don't you think?" but just, "Don' you?" The "think" is understood. I would be less than a gentleman if I told this small girl, "Yes, I think so." I insist that she has a very good head. She is learning English quite fast.

"No, Papa-san—ba-ad head! Today morning I'm forget sun gu-rasses anda camera. Engrish speaking, Papa-san, 'hat you say—somebody's house?"

"Somebody's house? I don't get the connection."

"Maybe anybody's house. Papa-san don' understand anybody's house?"

"No—I mean yes, I don't understand."

"Watsamatta you, Papa-san?" and she taps her forehead. "Somebody's house—anybody's house! Maybe srang speaking!"

"Slang? Oh—you mean nobody home?"

"Yiss, of-a course, Papa-san."

Now, where did she learn that? It dates back to "Twenty-three Skidoo" and other nifties of the eens. Papa-san is still chuckling to himself a couple of kilometers later. Not another sports car is in sight. Nothing to make it certain that we are still on the right road....

"You think this is right, Richi-san?"

"Right? Migi, Papa-san?"

"No, not that kind of right. You see, we have several words in English, all pronounced 'right.'" (What was that I said about haré and haré?) "One means migi, the opposite of hidari. One is spelled w-r-i-t-e, like when you write a letter. Understand?"

"Oh, Papa-san, I'm forget! Day behore yesterday come to my room a retter, Kyobashi aunt and husband—'hat Engrish speaking—maybe unc'? Yiss, Kyobashi aunt anda unc' retter writing, speaking, 'Harro, Papa-san, sank you verree much.'"

"Well, that's certainly nice of your Kyobashi aunt and uncle, Richi-san. You tell them hello for me, please. Now... we have another word, r-i-t-e, but we won't go into that now. When I say, 'Is this right?' I mean are we still on the right road? Is this the road to Hakone?"

"Papa-san, stop. I'm-a risten."

"You'll what?"

"I'm-a risten," says Richi-san, cupping her ear.

That's plain enough. She will ask a question, and listen for the answer. We stop. She hails the nearest person, a woman wearing a kimono.

They bow. The air is filled with greetings and salutations and pleasant amenities. Each chatters at length while the other nods, interjecting occasional "Ah, so?" sounds along with "Ha-ha!" and "So desu ne?"

The minutes pass. Papa-san fills his pipe and smokes. He thumbs idly through the Japanese dictionary and observes that kami means not only the hair Richi-san fears will be all bu-roke by the wind, but also the Romanized spelling kami means deity, paper, the head, and season. Probably to season food, because it also says, "to add one thing to another." This is all very interesting, but meanwhile the other sports cars are somewhere down the highway, collecting points, and we are very probably on the wrong road. Now Richi-san thanks the woman, and the woman thanks her. Both bow several times and repeat, "Sumimasen" which means "I'm sorry to have bothered you." They say, "Sayonara." We finally get under way again.

Richi-san turns to me, her small face glowing with good will.

"Ver-ree kindness, Papa-san! Good-a heart—don' you?"

"Yes, I think she must be a very kind woman, Richi-san, and she has a good heart. But what about the road to Hakone?"

"Oh, Papa-san, Hakone road she don' know." You can lose an awful lot of Sports-Car-Club runs that way, in this charming country....