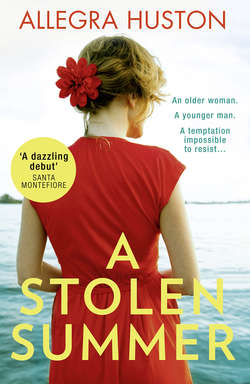

Читать книгу A Stolen Summer - Allegra Huston, Allegra Huston - Страница 7

Оглавление1

There, under a table heaped with china of the sort nobody uses anymore, she spots it, almost hidden behind random objects carrying price stickers faded by time. Daylight filters through grimy windows onto worn green velvet, golden wood. Strangely, the case is open—as if it’s hoping to be found.

It’s bigger than a violin, much smaller than a cello. It’s fat, squarer than most instruments of its kind, with an elongated neck, and—this is what draws Eve in—encrusted with vines. The fragile carvings seem greener. They were once painted, maybe.

Eve moves the piles of junk aside so that she can crawl under the table. Usually she wears jeans for these expeditions, but it’s a hot New York summer, so this morning she chose a thin dress, counting on the intricate print to disguise any smudges. It will rip easily, though, so she tucks up the sides into her underwear to keep it off the floor.

As she crouches down, the bones of her knees crack. Though she’s fit and strong, her forty-eight-year-old body is starting to show age. Her brown hair has almost no gray in it—good genes, her mother would have said—but soon she’ll have to decide whether to color it. She’s never seen the point of lying about her age and, being married, she’s less concerned about looking young than she might be if she were single. Still, the ugly milestone looms. She’s tied her hair in a ponytail and covered her head with a scarf to protect against cobwebs.

By profession, Eve is a garden designer. Her husband, Larry, makes enough as a product development manager for a pill-coating supplier to pharmaceutical companies to enable him to treat her little business as, basically, a hobby. This annoys her, but the truth is, she treats it that way too. Taking it more seriously would mean confronting Larry and claiming ownership of her time and priorities, which she is not prepared to do. The status quo feels fragile, although it also feels as lasting as mortal life allows. All that’s required is that she keep the delicate political balance, and doesn’t rock the boat or disturb the sleeping dogs. She’s gotten into the habit of not pushing any communication past the minimum required for practical matters and the appearance of enough closeness to assure her that their marriage is sound.

On weekends, guiltless and free, she searches out treasures for her friend Deborah’s antique shop. Larry doesn’t complain; she suspects he’s glad to have the house to himself. For her part, she’s glad to be away from it. The strange objects she finds ignite her imagination, conjuring up lives more exciting, and more terrifying, than the low-intensity safety of her own. Today she’s exploring a northerly part of New York City that, like a tidal pool left by successive immigrant waves, houses people from nations that may or may not still exist: Assyrians, Armenians, Macedonians, Baluchistanis. The alphabets in which the signs are written change block by block. Neighborhoods like this are her favorite hunting grounds.

On her hands and knees under the table, she tugs at the instrument in its case. It shifts with a jerk, leaving a hard outline of oily dust on the floor. Probably it hasn’t been moved in years. She lifts it up onto a tin chest, keeping her back to the storekeeper to disguise her interest.

The vines twine over the body of the instrument and up its neck, stretching out into the air. Though the delicacy of the carving is almost elfin, it has the strength of vines: blindly reaching, defying gravity. The tendrils are dotted with small flowers: jasmine, so accurately rendered that Eve identifies them instantly. A flap of velvet in the lid conceals a bow, held in place by ribbons. It, too, is twined with curling vines.

She wiggles her fingers into the gaps between the instrument and the velvet lining, prying it loose. A moth flies out into her face and disappears in the slanting shafts of light.

Holding it by the neck, she senses another shape. With spit and the hem of her dress, she cleans away the dust. There’s a pudgy, babyish face, the vines tightening their weave across its eyes. Cupid, blinded by love.

Eve pinches up dust from the floor to dirty the face again. She has learned not to improve the appearance of things until after the bargaining is done and the money has changed hands. Then she turns the instrument over.

The back is in splinters.

Eve touches her finger to the ragged shards of wood, longing to make this beautiful thing whole again. The damage must have been deliberate: an accident would have broken off the vines. What drove that person over the brink? Musician’s frustration? Rage at fate? Heartbreak? She can almost feel remnants of the emotion stuck to the gash, like specks of dried blood.

If she had it repaired, the cost would almost certainly be more than the instrument is worth. And even an expert might not be able to restore it completely. It could serve as a decorative item, but only if the gash stays hidden. Deborah won’t want it—she has a rule against broken things. Also, she feels more comfortable with things that have names, like bowls and vases and candlesticks. Passionless things that sit prettily in nice rooms. The history that this object bears on its back would freak her out.

Eve moves to return the instrument to its exile, but she can’t bring herself to do it. Now that she has touched it, she cannot push it back into the shadows.

It’s an extravagance, driving into Manhattan: the cost of parking; the idling crosstown traffic. But Eve needed her car for her expedition to the outer boroughs, and she is not ready to go home to New Jersey. She finds an expensive space in an elevator lot, and starts walking the eight blocks to the Public Library. She leaves the strange instrument, in its case, on the back seat beside a curly wrought-iron birdcage she picked up earlier.

“Eve? Eve Armanton?”

She looks around, unsure where this urgent voice is coming from. She has barely heard her maiden name since college.

“Eve! I can’t believe it!”

“Robert?”

Robert Burnett, her brother Bill’s best friend. And, beside him, a younger man who must be his son. The pair of them hit her like an optical illusion, a thirty-year warp in time: Robert now and Robert then, standing side by side on 34th Street. The son is, Eve realizes, even more beautiful than his father used to be, with thick black hair, a finely cut nose, and angled eyebrows over long, wide-set eyes. Age has dragged Robert’s once-fine jawline into jowls, and thinned his hair. The bright blue eyes that enthralled her when she was fifteen are murky, and there’s a sheen to his skin as if the cholesterol in his bloodstream is seeping through.

Back then, Robert reminded her of Tigger, with his bouncing energy and his recklessness. He and Bill were twenty-two: college roommates, party boys, the world at their feet. Everything seemed to come easily to Robert—but Bill saw shadows where Robert saw only the light. Robert’s wildness was pure exuberance; Bill, Eve sensed with a teenager’s unspeakable anxiety, was daring fate, as if hurrying up the tragedy he knew would surely come. Eve has barely thought of Robert since her brother’s funeral. After Bill’s death, she cut off all connection with the elements of his life, terrified that the darkness that drove him to suicide might invade her too.

Robert moves more slowly now, his boisterousness reined in by years of office-bred decorum, the crazy Hawaiian shirts he used to wear replaced by a well-cut suit, pink shirt, and brightly patterned tie. She knows what he wants to do, and she will let him do it, for old times’ sake: sweep her up in a hug and spin her round and round until they both get dizzy. Bill used to do that when he saw Eve after a gap of weeks, and the fact that Bill did it became Robert’s permission, a fond mastery over his friend’s little sister, whose adoration he accepted, without comment or attention, as his due.

Robert’s arms lifting her feel as strong as they always did. Cars, pedestrians, storefronts whirl past in a circular blur. Eve scrambles for a reference point, as she was taught in childhood ballet class, and there it is, like a hook catching her searching eyes: the younger man’s gaze, his eyes a startling green, strobing as Robert whirls her around.

Finally, she feels concrete under her feet again. Robert keeps hold of her arm to prevent them both from falling. Bill used to love it when she fell over: a big brother’s affectionate cruelty.

“How long has it been?” Robert’s face is alight with the pleasure of finding her.

“Twenty-nine years. Almost.”

“The funeral.”

Eve nods. It took place in November. Leaves stripped from the trees, naked branches that made her think of her brother’s dead bones.

“You remember, we had a baby with us? Well, here he is. Mick, meet Eve.”

“Micajah,” he says, gently correcting his father. A name she’s never heard before. Mic-KAY-jah. She likes the roll of it.

He holds out his hand. “Eve,” he says.

She’s reluctant to touch him, as if she might be touching an electrified fence. As his fingers close around her hand, her nerves register the calluses on his fingertips. She drops her eyes. He’s wearing jeans and a loose blue shirt, the sleeves partly rolled. His feet, in hiker’s flip-flops, are sinewy, with long toes. She feels suddenly that she shouldn’t be looking at them, these body parts naked to her gaze.

“Eve’s brother taught me everything I know about music,” says Robert. “Which, granted, compared to you, Mick, isn’t all that much. My son, I want you to know, Eve, is a rock star.”

“I play in a band.” His voice is low, almost hoarse—nothing like Robert’s. His words are no more than an explanation to tone down his father’s boast.

“Inked the last clauses of the deal this morning.” Robert pats his son’s shoulder. “We’re celebrating with lunch. Join us, Eve! Whoever you’re meeting, stand him up!”

This is the Robert she knew: someone who embraced the world with such total disregard for the possibility of rejection that it couldn’t resist him. He was always on to the next thing, always excited, as forceful as a tornado. It fascinated and frightened her, the way the past just fell away behind him into a detritus of facts stripped of meaning. She used to wonder whether anything could really be precious to him.

In memory of Bill, Eve says yes to lunch.

“It’s an old Shaker name,” Micajah tells Eve as they walk, in response to her question. “My great-great-great-great-grandfather’s brother was an architect, the first Micajah Burnett. The first I know of, anyway.”

“I visited a Shakertown in Kentucky once,” she says, “when I was driving my son to college. It was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been.”

She remembers the elegant symmetry: twin staircases, twinned rooms, to keep the men and the women apart. And the sense of tranquility, which she imagined had always reigned there, since there were no marriages, no children, no sex.

Micajah has his father’s excellent manners; but, where Robert held chairs and doors the way a peacock holds his splayed tail, Micajah holds Eve’s chair for her in an offhand way, as if in casual rebellion against the carelessness of the world. Eve never agreed with the militant college feminists that such manners were insulting; she taught her own son to hold doors, though not just for women. Once she stood outside the door of the bank for several minutes as people went in and out, waiting for the eight-year-old Allan to realize she hadn’t followed his heedless rush toward the M&M dispenser inside.

“Looks like you were scrubbing floors this morning.”

She noticed Micajah registering the grubby hem of her dress and the smudges on her knees as she sat down. She’d tried to wipe them clean in the car, but the dirt had ground itself into her skin.

“I was dragging something out from under a table, in a junk shop in the Bronx. I was on my way to the library to research it when your father waylaid me.”

“That’s cool,” he says. “That you don’t care your knees are dirty.” The corners of his mouth turn down when he smiles, as if he’s keeping back some of his amusement for himself. “What was it?”

“A musical instrument. I don’t know what you’d call it. I’ve never seen anything like it before.” Eve isn’t sure if he’s teasing her. Luckily, the instrument makes a convenient conversational shield. “It’s like a violin—strings and a bow—but squarer, with a really long neck.”

“Sounds like the kind of thing Mick plays,” says Robert. “Weird contraptions that don’t even have English names.”

There’s a sudden edge in his voice: annoyance, or jealousy? Praising Micajah, he was feeding his own ego, Eve realizes, and she dislikes being his audience: for the showing off and the putting down. She’s starting to wish, for more than one reason, that she hadn’t agreed to join them for lunch.

“My dad thinks I’m a terrorist,” Micajah says, unruffled. “Because I play music from places where the State Department doesn’t want you to go.”

His vibe is somewhere between bohemian and outlaw.

“Well, if it makes you millions, I won’t complain!” Robert’s laugh is a braying bark. Eve sees the couple at the nearest table stiffen and pretend to ignore him.

“Yeah, all that money,” says Micajah quietly. “I’m planning to spend it on gold-leaf underwear. Not ostentatious. Just for that coddled feeling.”

The corners of his mouth turn down. His eyes, mischievous, catch Eve’s. She feels a trickle of sweat run down her back, even though it’s cool inside the restaurant. The sports bra she chose for her hunting expedition feels like an implement of torture around her chest.

“You’re going to move out of that roach motel,” Robert says. “Buy something that’s going to appreciate.”

“I appreciate where I live now,” says Micajah. Then, to Eve: “Did you buy it?”

“Yes.”

“You’re a musician?”

“No. But even if I was, it’s not playable. The back is smashed.”

“So why did you buy it?”

“It’s beautiful,” she says.

“And you couldn’t just leave it there.”

She feels transparent to his eyes.

“If it wasn’t broken, I probably couldn’t have afforded it,” she says. “It has this incredible carving, vines, twining all over it. I’m pretty sure it’s jasmine. It made me think of the secret gardens in children’s books. Or The Arabian Nights.”

“How the hell do you know it’s jasmine? It’s wood, for Chrissake.” That’s the spoiled-brat side of Robert: hating not being the center of Eve’s attention.

She reaches into her purse for a business card, and gives it to him. “I’m a garden designer now. I use jasmine a lot. It’s resilient, it lasts all summer, and it smells delicious when you sit outside in the evenings.”

Robert holds the card at arm’s length, as if he doesn’t believe what’s written on it. Eve had no particular interest in flowers back when he knew her. She gets the sense that he considers her change over the years as a kind of betrayal.

Micajah is glancing from his father to Eve, clearly wondering if they were once lovers. They weren’t. Eve is a little shocked by how much she cares that Micajah should know that. As the little sister, she had a Don’t touch sign plastered to her forehead. When Bill died, she went to the funeral with the guilty thought that maybe the extremity of emotion might propel them into each other’s arms. She hated herself for this callous disloyalty to her brother, allowing her desire to contaminate what should have been the purity of her grief. She didn’t know, before she got to the church, that Robert was married with a baby son.

The waiter arrives, a plate in each hand and the third balanced on his wrist. He gives Robert his steak, Eve her salad. Conscientiously, she ordered from the cheaper end of the menu.

“Saltimbocca,” the waiter says, setting Micajah’s plate on the table, twisting it to its most advantageous angle. “Jumps into the mouth. That’s what it means.” He’s flirting, helpless as an iron filing in Micajah’s magnetic field. Earlier, when he took their orders, Eve registered his agitation. She feels a pang of sympathy for him. Women used to be like that around Robert. She’d seen girls chase him down the street and force their phone numbers on him. He gloried in it with the laziness of a lion.

“Thanks, Josh,” Micajah says, remembering the waiter’s name from his spiel earlier, and meeting his eyes for a short moment before turning his attention back to Eve. Elegantly done, she thinks—a masculine gentleness his father never had.

“At least it’s not roses,” Micajah says.

What if the carved flowers had been roses? Would she have bought it? Maybe not. It was the jasmine—secretive, blooming in darkness—that seduced her.

“I hate roses,” he adds.

“Why?”

“Drag queens of the flower world.”

“Meaning what exactly?” his father chimes in. He looks from Eve to Micajah, Micajah to Eve, like a boxing referee before saying the word “Fight.”

“The whole sickening cultural orthodoxy of them,” Micajah says. “The fake valuation, like that ‘a diamond is forever’ crap. The environmental destruction of the factory rose farms, gobbling up the land in places like Kenya while the local people starve. It’s like their whole purpose in the world is to lie. I screwed around on you, darling, so here’s a bunch of roses. And that’s not even getting into the S&M of it. A symbol of love that makes your fingers bleed? Except, no, let’s pretend roses don’t have thorns, and hire slum kids to slice them off with razors.”

“He’s a hothead,” says Robert.

“I care,” says Micajah. It seems like an old battle between them.

“Do you really think it’s possible to have love without hurt?” Eve asks Micajah, then wishes she hadn’t.

“I don’t know,” says Micajah. “Is it possible to love deeply and choose not to feel the pain? Hell, it’s worth a try. Because if you don’t, what happens? You end up wrecking what’s beautiful.”

Like Bill. And like that unknown person who smashed the instrument but couldn’t bring himself to destroy it completely.

“Are you going to get it fixed?” Micajah asks Eve. “Or, you like broken things.”

It’s a statement, not a question. Again, she feels him looking straight into her heart. Flustered, she glances around the restaurant: the other diners chatting and laughing, the waiters moving competently about, the gerberas in vases on the tables.

“What were you doing in a junk shop in the Bronx, anyway?” asks Robert. “Looking for secondhand plants? I guess you found one!” That barking laugh again.

“Scouting for a friend’s antique shop. It’s what I do on weekends, sometimes. Now that my son’s grown. Allan.” Even after twenty-four years, she feels a warmth in saying his name. “He’s in Cambodia right now, taking a year off after pre-med, working for Smile Train.”

“What’s that?” asks Robert, though he doesn’t sound genuinely interested.

“A charity that fixes cleft palates on kids,” says Micajah. “That’s seriously cool,” he says to Eve. “You’re proud of him.”

“I am.”

“You should be proud of yourself too. You brought him up right.”

Flustered, she manages a half-smile in response. She’s glad she doesn’t know what to say, as she doesn’t trust her voice. Whatever words she’d find might come out as a squeak, or shaky, or have no sound at all.

“I’d never think you could have a grown son, if I didn’t know better,” says Robert with automatic chivalry.

Eve feels a warm, gentle pressure against her foot. As she looks to Micajah in surprise, the pressure vanishes. Imperceptibly, he shakes his head.

No, what? Eve wonders. No, don’t respond to him? No, you don’t look younger than your age? No, you do—or you don’t—but it doesn’t matter?

Eve takes a drink of water and smells muskiness on her skin. There’s a melting sensation at her core: her body is rushing ahead on a path she knows she should not follow. This boy—he’s a boy, she insists to herself, though she knows he must be twenty-eight or twenty-nine—is throwing her off her axis. In college, she lived for that feeling. Before today, she thought she’d outgrown it, and comforted herself in the dull succession of her days with the relief of knowing she would never feel that fizzing confusion again.

When she dares to look back at Micajah, the green gaze is like a wave rushing across the space between them to drench her, sweep her up, carry her away. Stop! she thinks. But she does not want it to end.