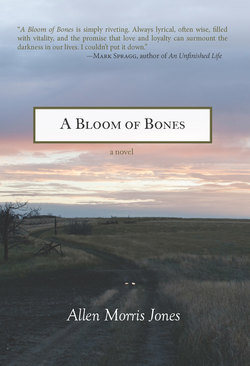

Читать книгу A Bloom of Bones - Allen Morris Jones - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI SAID, “THAT BIG BULLET went right on through, didn’t it?”

It was too cold to snow but still it was snowing; a thin sheet of gauze twisting around the porch light. Buddy kicked through frozen marbles of blood, scattered at them, swept them aside with his boot. He knelt and rose, hoisting the body across one shoulder. Voice muffled by a wool scarf, he said, “Leaking?”

“What?”

“Is he leaking anywhere?”

“I don’t see it.”

“All right then.”

“That big bullet went plumb through, didn’t it?”

“Will you quit with the goddamned questions? Just for once?” A gentle man, Buddy rarely cussed, seldom rebuked, never raised his voice. I stood abashed, one breath from tears. He inhaled hard through his nose, shifted the body on his shoulders. “Let’s just get this done.”

He set off toward the county road, walking fast. I ran to catch up. To the east, it was fifty miles of dirt until you hit the two saloons and five churches of Jordan; to the west, nothing but the Musselshell. At two in the morning, and barring high school kids off on a jacklighting drunk, there’d be no traffic. We had the road to ourselves.

I huffed along beside him. “You ain’t taking the truck?”

“You want Pete’s blood all over my truck bed?”

“No. I guess that’s right.”

He glanced down. “You can get on home if you want. No use for us both.”

“I want to help.”

“All right then.”

“Where we taking him?”

“I was thinking Cherry Creek. All them little eroded holes.”

“Oh sure.”

Our breath bloomed blue around us.

Up on the road he said, “We don’t want to leave no tracks. Careful just to step in the ruts.”

“All right.”

“Just step where I step.”

“Okay.”

He shifted the body. “It sure turned cold on us didn’t it?”

It was so quiet. The squeak of our boots on the snow recalled nails twisting in boards. We were the first or last men on earth. Lone survivors of an epidemic, an ice age.

Eye level in front of me, bouncing against Buddy’s back, Pete’s shock of hair had frozen into a stiff brush of frost, a rigid, cartoonish explosion of fright. His eyes were open, and a rime of snow had collected in the lashes.

After a time, Buddy left the road. He stood waiting for me to open the gate. Grabbing the post, my gloves came away scaled silver with hoarfrost. He led us a hundred yards or so into the pasture before dropping one shoulder, letting the body slump off into the snow. He stretched his back and studied the sky, the stars showing through. “Looks fair to clear.”

It was a porous ground around us now, hidden under the drifted calluses of old snow. A honeycomb of ditches and pipes carved before the spring had been piped and controlled. Buddy began walking in circles, kicking at drifts. “That good round one’s around here someplace.” After a time, his boot broke through, revealing a vertical chimney as straight as a small highway culvert set on end.

It was deep but narrow. Pete’s legs, cocked to the shape of Buddy’s elbow, were going to make him half again too wide. Buddy pressed down hard on the knees, trying to force them straight. But the combination of freezing and rigor kept bouncing them back. Finally, Buddy pulled off a glove and reached into his overalls. “Haul one a them legs up here.”

I grabbed a heel and raised it, with difficulty, to my waist. Both legs came together, paired in a posture of obeisance. Buddy blew into his fingers, unfolded his knife. He forced the blade under the cuff of Pete’s frozen jeans and started cutting. One hard cut up, then another, then he was sawing freely through the wrinkles.

Above all other things, Buddy was a pragmatist. He knew how to keep calm during a crisis. When the grease popped hot across the pan (his own words), he prided himself on approaching the world with the coldest kind of eye.

Now he folded the fabric back to expose Pete’s hairy shin and calf. The skin gray, freezing. When he pressed his blade to the soft patch of flesh below the kneecap, that place where a doctor tests the reflexes, the skin split into a narrow, bloodless mouth.

I could see that Buddy had expected this to be a good start, for the skin to pull loose as it did with elk and deer. But human skin, it seems, holds to a tighter standard. He worked his knife hard around the knee, grunting. “Damn if old Pete ain’t about as hard to skin as some old beaver. Beavers, now, there’s some tough skinning.”

Eventually, the blade cracked hard into the joint, popping between cartilage and bone. Buddy worked at it until the leg wobbled loose in my hands. He motioned me away, taking the foot and bracing it on his lap, twisting it hard, heel to toe. Tendons popped and snapped. He twisted it again, then again. Then the leg span freely, caught now only by a remnant of fascia. He cut these last strands away and tossed the leg into the hole: boot, hairy calf, loose athletic sock. Then he treated the other leg just the same.

“Can I close his eyes?”

Buddy touched his dripping nose with the back of his hand. “Help yourself.”

Bending down to Pete, I found his pupils fixed and white, frozen opaque. Closing his lids was harder than you’d expect. It wasn’t like the movies where all it took was one magic pass of the hand. No. The lids rebounded with a slow, stubborn resiliency. A stitch of thread was needed, or barring that, a pair of coins. I had a quarter and a penny.

The quarter wanted to slide down his cheek. I spat on it and held it in place until the spittle froze. Then I treated the penny just the same. Given the way his mouth was hinged slightly open, the lopsided shine of the coins, his face was given a waggish leer, a wink and grin. He was sharing some private joke. Maybe I was the butt of it. Pete had always hidden his insults inside a jibe. This felt like a proper face for him to take to the grave.

Buddy tilted the body over into the hole, lighter now without its legs, and began stomping at the sides of the hole, shearing off frozen plates of clay with his heels. “We’ll come out here in a day or two with a shovel, finish the job. Maybe turn out a few steers to chop up the ground some.”

It didn’t take long, only a few minutes. Already it seemed impossible that Pete should be down there, legless and dumb.

I watched, surprised, as Buddy next unbuttoned his trousers, dug through his layers of long johns. Finally stood taking a heavy piss into the half-filled hole. Steam rose as if from a crack in the earth. As he turned back, tucking himself in, I expected a grin, a joke. But he only looked old; he looked tired.

Later he handed me the pocketknife he had taken from Pete’s trousers. A little deer horn, lock-blade Buck. “Put that in your pocket. You’ll need you a remembrance.”

As if I would ever be able to forget anything about that night. Or what came before.