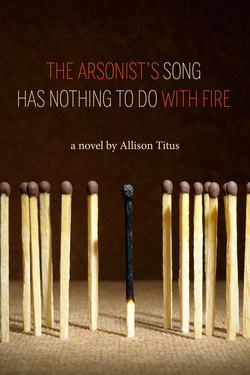

Читать книгу The Arsonist's Song Has Nothing to Do With Fire - Allison Titus - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRonny Stoger was not a career man nor a tradesman nor a man with management potential, per se. Ronny was a peddler. He worked at the quarry off Graverton is what he’d tell anyone who asked. Meaning he worked at the gift shop and junkyard adjacent the quarry, Concrete Jungle, a place that salvaged claw foot tubs, pinewood church pews and broken desks, but specialized in the sale of concrete squirrels and deer meant for gardens. For example, concrete birdbaths, concrete pigeons. Concrete giraffes, rabbits, monkeys. The whole lot was bland, stationary, stony—of course. But the stillness bothered Ronny some days more than others. Why domesticate cement?

The town Ronny lived in was a town of lesser-known fast food restaurants and colored glass repositories. There was a minor college, and for those kids there wasn’t much more than the pool hall, which had two pool tables, a mechanical bull that was mostly out of order, and dollar pitchers after eight. There was an old movie theatre downtown, a dry cleaner’s, a post office. Must be more, but that seemed like most of it as far as Ronny could tell—not much had changed. He’d been back at his father’s house for almost three months, out of juvie, done with service hours. Anyhow, his mother wanted him out, not stuck there after everything. Because Ronny set fires. Small fires, sure, but left to their own devices—caught on the wind, for example—small fires might forge a remarkable blaze.

On days this foggy, the quarry disappeared. The clouds filled in the gap so you could walk right up to the edge before you realized you were standing over the pit, a 250-, 300-foot drop. Days like this no one came around. The camps got off for zero visibility but Ronny still had to man the yard till dusk. He brought in six-packs to pass the time; he propped his feet on the desk, leaned his head back against the wall, thought about how he was too old for this. Most everyone he’d known was out of Central by now, if they’d gone, or done with hair dresser school or auto repair or refrigeration or funeral services training. Whatever people did, they were doing it. Cutting hair, fixing cars, pressing shirts for dead bodies.

This line of thinking got him restless. What the men at the quarry did was actual work, work that required safety gear and callused hands. He knew because the foreman owned this place too and he stopped in sometimes near end of day, with his hardhat and vest and roughed up grip.

Ronny stood, finished his beer and lined it up with the other cans on the desk. The office was too small to pace. He half-kicked the trash bin, toed it to the wall. He pulled at the dime store bell yarned to the door handle that rang for customers. He looked out and made sure. No customers. He pulled at the filing cabinet drawers for no reason. They were rusted and shrieked open to reveal office supplies mostly, envelopes, old paperwork. In the third drawer down he found the bank deposit bag, right there on top, bingo. His boss hadn’t turned it in. He unzipped it, it was pretty slim, pulled out a bill without looking, slipped it in his back pocket. Not a big deal but his heart beat faster, slightly, because it was an asshole thing to do, to steal from your boss for no reason except you were shitty bored. He sat back down at the desk and opened another beer.