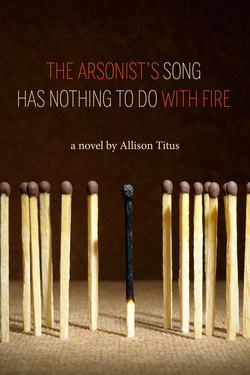

Читать книгу The Arsonist's Song Has Nothing to Do With Fire - Allison Titus - Страница 29

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVivian stood squinting in the dusty lobby, her eyes slow to adjust to the new brightness. The running guy and Vivian were the only two people around, besides the teenager who left the box office with a push broom and a woman at concessions. When Vivian came out of the theatre, Ronny had been talking on the payphone stationed across the lobby, between the restrooms. Vivian bent to tie her shoes which turned out to be boots and did not have laces. She adjusted the knees of her tights instead, pulling straight the ribbing. She was buying time. When he hung up, Vivian hesitated, then surprised herself by waving. He shrugged and headed across the room to where she stood, the ice maker grinding to a halt behind them.

“Hey, sorry to bother you, I was thinking you live on my street. Well I’m house-sitting, actually, so, where your neighbors live. I’m Vivian.”

“Vivian,” he hesitated, “Hey. I’m Ronny.”

“Yeah,” Vivian said, for no reason.

Ronny nodded, thought about something. “You’re staying in the house across the street then. I heard about that, the professor.”

“I moved in a few days ago,” she nodded.

Ronny had never met the professor. Paul and Helen had only lived on that street for about a year, a little more than the time Ronny had been gone. He remembered the moving trucks back then, and he remembered the cop cars that came a few weeks ago, started showing up in the mornings, one undercover and one squad.

His manner was quiet and a little distracted or preoccupied with something else, more than that lobby and whatever she would manage to say next. He was only vaguely interested, not committed to the details, she could tell. Ronny wore a brown sweater, had longish hair that was growing shaggy. There was something familiar and withdrawn about his face, and careless, the beginning of a beard. A patch sewn in wrong over his pants knee. He was slim, but rugged, like a boat maker. Like a boat maker who rose early, heaved planks for hours at the lip of the river and didn’t own a TV.

“Well,” he said, a suggestion they should move on. An usher was locking the bank of doors behind them; a manager carried a clipboard back to the registers. It was late.

Outside he paused to light a cigarette. He wasn’t supposed to have a lighter. But you could get your hands on anything. You got by. He needed to go back and check the place out but with Vivian following him . . . He took a long drag and started walking home. She fell in slightly behind.

“How’d you know where I was staying?” Vivian said to the back of his sweater.

He shrugged. She watched the orange spark between his fingers lift back and forth.

“Saw you the other day,” he said, “Taking the newspaper in.”

She nodded. So he’d noticed her. It was an idea she felt in her stomach: she wasn’t the only one paying attention, or hadn’t been. He was obviously in a hurry to do something, though, and she was losing him to it.

“So where’s the fire,” she said.

He turned, quickly, checked her face for something, some sign, who knows, and went on walking.

“What do you mean,” he said, not like a question.

She’d said the wrong thing, of course; she’d never gotten the hang of small talk, of how to be casual enough with all the questions you were supposed to use to learn about another person. There was an etiquette to it, a pattern that seemed to be natural for everyone else but which Viv ruined, overthinking every word. Overanalyzing every exchange, aware there were shortcuts and codes, but what were the rules, it was a gamble. So she was always saying dumb things. Really, what it came down to was the peculiar deficiency of not understanding how to be known by anyone. She didn’t want to give too much away. In fact, she was embarrassed to even be seen bending down to the tray of a vending machine, retrieving a bag of Fritos from the drop bin. How could a person stand to always be seen desiring, and taking. Not just food, either—anything coveted. To Viv, every kind of hunger felt vulgar, and that was an embarrassing kind of shame.

To Ronny she said, “What’s the rush, when I saw you before you were running, that’s all, now you’re walking so fast, it was a dumb joke you know—forget it.”

She’d caught him off guard and it was uncomfortable, a shift that put him under inspection, because when had she seen him before tonight, he wondered, running?

“Yeah, well,” he finally shrugged. Something bothered him. Half-heartedly he tried but could think of nothing to say.

Ronny kept his head down. They walked in awkward silence, got past another block without talking. Ronny smoked as he walked, and pictured each house they passed going up in flames, thinking how you could see every second ending if it was set on fire. Every second burned off the present.