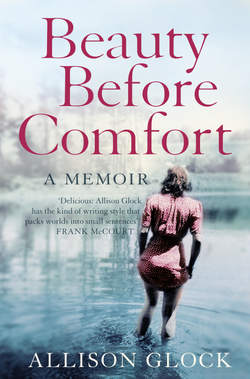

Читать книгу Beauty Before Comfort: A Memoir - Allison Glock - Страница 8

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеThe state of West Virginia was born in conflict and has retained lo these many years a mulish attitude problem. The people born there are chippy. It’s a birthright.

The state came to be in an act of war, when the western half of the state broke off from its eastern parent, Virginia, in 1863. The two sides disliked each other with familial intensity. The western half envied the wealthy eastern half. The eastern half was ashamed of the western half. The westerners saw the easterners as idle slave owners. The easterners saw the westerners as boorish rednecks.

“What real share insofar as the mind is concerned could the peasantry of the west be supposed to take in the affairs of the state?” said easterner senator Benjamin Watkins Leigh on the floor of the 1829 Virginia legislature.

“Screw you,” said the peasantry of the west.

Western Virginians were sick of the ridicule, of being overlooked when it came to building schools, of being dismissed as “woolcaps” by the richies who lived in the pampered south of the state. Then, around 1850, the state of Virginia borrowed $50 million for improvements and the construction of roads, canals, and railways. The only money spent in what would become West Virginia was $25,000to build the “Lunatic Asylum West of the Allegheny.”

It was not a promising precedent, and the two regions formally went at each other’s throats. The rivalry played out in the legislature for years, until finally President Lincoln stepped in and pressured Congress to push Western Virginia’s independence through. This decision “turns so much slave soil to free,” he said. It was “a certain and irrevocable encroachment upon the cause of the rebellion.”

Thus was born a state and the lasting tradition among its people of giving whomever they please the finger. “Mountaineers are always free,” declares the state motto. This history was not lost on my grandmother.

Aneita Jean Blair was born at the foot of her mother’s bed on September 30, 1920.

“I was born ugly,” my grandmother says. This is a lie, but it is a lie she believes.

In the album, there is only one photograph of the infant Aneita Jean. It was taken on the Fourth of July and she is roosting on her father’s knee, a lump in white cotton, with a black wick of hair falling down her forehead. Beside her, her two-year-old brother, Petey Dink, rests an American flag on his shoulder, his free arm raised to shield his eyes from the sun. A horse and buggy is parked behind them. It is impossible to tell if she was in fact ugly, but, given the gene pool, it seems unlikely.

On the day my grandmother entered the world, it was storming, and because her mother always kept the windows open, Aneita Jean Blair was not only ugly but in the rain. When her father rushed into the bedroom, Grandmother was already there, pinned down by her mother’s foot, wailing and kicking in a runnel of wet. It is because of this that she says she is crazy.

“I’m crazy, you know,” she’ll tell you soon after you meet her. She is indiscreet. She tells the grocery clerk she’s crazy, the bank teller, the librarian. She once met a boyfriend of mine, grabbed his arm, told him she was crazy, then suggested the two of them climb into a dog crate and “see what happens.”

Aneita Jean weighed seven pounds at birth, a weight she would more or less carry until the first grade. She was a colicky baby, a crier. She spent the first years of her life in a foul mood, believing even then that a life without beauty is a pile of slop.

In a photo of her as a toddler, Aneita Jean is standing outside, her mouth screwed into a knot of agony, her hair sticking up like a pitched tent. When she was two, her older brother, Petey, had given her a doll that frowned, which made everyone laugh, but which she despised and pinched when no one was looking.

“Everybody thought it was funny,” she says. “I didn’t think it was so damn funny.” And then: “Buster Keaton never smiled, either, and everybody was mad for him. Ah, horseshit feathers.”

In public, Aneita Jean would stand eyes forward, lips flattened, hair chopped close to her neck, reeking of defiance and looking lifetimes older than the little girls next to her, with their eager smiles and shy eyes. Family lore has it that it would be a full three years before she ever smiled. Three years, never so much as revealing a tooth.

I’m going to leave here one day,” she’d say to her mother years later, her head nestled in her lap.

“Why would you go and do a thing like that?”

“Because.”

It wasn’t much of an answer, but then, as a little girl, she hadn’t really thought it out. It was an instinct. She was going to leave, become a painter or a singer; she was going to wear dresses with sequins and make art and meet dark men in suits who smoked pipes and nodded their heads in approval.

“No one leaves here, Jeannie,” her mother, Edna, would chide, tucking a curl of hair behind her daughter’s ear. Edna herself had moved only twice, arriving at the new spot within a few hours of the last.

That few people escaped West Virginia was true, but an irrelevancy to Aneita Jean. Ugly or not, she decided that by the time she was sixteen, she’d find a man who would carry her over the mountains to a place where all the women lolled about, resplendent in chiffon and diamonds, and all the men looked like Errol Flynn before he started drinking so much. Someplace glamorous. Like Pittsburgh.