Читать книгу Girl - Alona Frankel - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHEY WERE ALWAYS WITH ME. THE LICE, MY LICE.

I was familiar with two kinds of lice, head lice and clothes lice. Only later did I learn of the existence of another kind, pubic lice, from the four-volume Encyclopedia of Sexual Knowledge that survived from the Jewish gynecologist’s library. The doctor himself, his mother, wife, two daughters, and baby son were murdered by the Germans. That was at the beginning of the war.

When Hania Seremet took me out of the village where I was hiding, pretending to be a Christian child, and dumped me at my parents’ hiding place, I learned for the first time the difference between head lice and clothes lice—an important and meaningful difference.

When I was in the village, the lice never bothered me. They swarmed all over me, and of course I scratched constantly. I thought that’s how it was in the world.

More than once, a careless louse would get caught under my nail. More than once one dropped out of my hair when I bent my head. What was the fate of such an adventurous louse that suddenly loses the head of its little Jewish girl? None of that worried me, everything was natural. Sleeping on straw in a coffin that was a bench by day and a bed by night. The horse, the cow, the stupid geese that nipped my ankles. The carrots, the corn, the wheat, the flowers. The mice, the lice, the bugs. The boiling potato soup that burned my palms and congealed into grayish vomit when it cooled. The old man, the grandfather, who spit his lungs out until he died, but not before he pulled my tooth with rusty carpenter’s pliers and rescued me from terrible pain.

It was my mother who was so very, very worried.

It was night when Hania Seremet dumped me at my parents’ hiding place. The room my parents were hiding in had two doors, one of them from the stairs. We never used that door, and no one imagined it could be opened, not even the building’s tenants. The room, a Jewish gynecologist’s office before the war, was now disguised as the carpentry shop of Mr. Juzef Juzak, carpenter and alcoholic. The other door was from the Juzaks’ apartment.

When the ghetto was about to be liquidated, the Juzaks were kind enough to hide my mother and father, but on one condition: that they come without the girl. Without me.

Softly, Hania Seremet knocked the agreed-upon knock on the staircase door. I sensed her anxiety and realized that fear has a smell. No one was allowed to see that door open. It would bring the Gestapo running, and that would be the end of all of us, including the Juzaks.

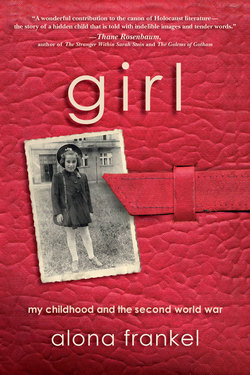

My mother, who must have been lying in wait for hours on the other side of the door, opened it instantly. Hania Seremet shoved me hard over the threshold. She tossed a bundle of papers and a bundle of rags, my clothes, after me. My green dress with the satin flowers, the one my mother made for me and sent to the village, the one I wore when my picture was taken with Hania Seremet in the photographer’s studio so she could send it to my mother and father as proof that I was still alive—in addition to my drawings, which she sent from time to time—the green dress wasn’t in the bundle of rags. Hania Seremet had obviously sold it.

Hania Seremet ran off quickly after finally getting rid of me. She must have breathed a sigh of relief, sure that we would all be dead before long. The smell of the sweat of her fear lingered.

Hania Seremet had wanted to get rid of me for a long time, but even so, she didn’t throw me into the street like she did Daniel, the sweet boy she left at the ghetto gate after his parents were murdered in an aktion and there was no one to pay to keep him in the village. The ghetto had already been liquidated when Hania Seremet got rid of me, but even so, she didn’t toss me into the street. Maybe she believed my mother’s lies about her connection to the underground—the Polish underground, the AK, the “Home Army,” whose members were not known as Jew lovers—and about their promise to kill her the minute they found out I was dead, and they’d do it even though I was Jewish.

The meeting had been set up in an exchange of letters that arrived in the Juzaks’ name, written in a prearranged code.

The door closed behind me. The key scraped in the keyhole. The bolt fell into place.

I stood there. I thought that’s how it was in the world.

I STOOD WITH MY BACK TO THE DOOR, MY PRECIOUS FORGED papers and the rags packed in a threadbare knapsack at my feet.

In front of me was a woman, my mother, thin and light-skinned, her lips sunken, her gold crowns pulled from her mouth in a series of exchanges—a gold crown for another week in the village, another week on the Aryan side, the side of life, the life of the child, Ilonka, my life. A man stood behind her, my father. I didn’t remember them.

I didn’t remember who they were.

My mother said, Ilonka, Ilusia.

My father struck a match stub and lit a lamp, or maybe a candle.

They looked at me, and looked and looked. My mother wept silently. My father covered his face with his hands and smoothed back his hair, leaving his hands on his forehead and eyes—a gesture that stayed with him till the day he died. His pale, high forehead invaded his dark, straight hair in two deep gulfs.

My mother picked me up, put me on the massive desk, undressed me and said, Ilonka, Ilusia, Ilitska. But I was Irenka. I knew that I was Irenka. I knew that I was Irena Seremet.

I saw and I was invisible.

In the light of the candle or the lamp—I recall a foul smell—the woman began inspecting me, checking every little part of my body.

My mother and father hadn’t seen me for months, and despite all the proof, the photographs and the drawings that Hania Seremet sent them, they hadn’t believed I was still alive. Every little part of my body astonished my mother profoundly. How healthy I was, how tanned. How many sores I had on my hands, how deep they were—my knuckles were scraped down to the bone from rubbing potatoes on the sharp, rusty grater. How shiny my cheeks were, so round and red. Like two apples, she said. How hard the skin on the bottom of my feet was—I’d run around barefoot in the village. How dirty I was.

And how I was teeming with lice.

She walked around me over and over again, and I wanted very much not to be there.

My father stood and watched, occasionally putting his palms back on his forehead and eyes.

My mother and father, who’d been in their hiding place for days on end, were pale, exhausted, and starved. My father had very large eyes, and my mother no longer had teeth. My father had pulled out all her gold crowns and bridges, the ones her brother Leibek, a dentist, had fitted her with after she’d come back ill from her pioneering escapade in Palestine.

My father had pulled out her bridges and crowns with his pocketknife.

My father’s expensive, amazing, ultramodern pocketknife, the Swiss pocketknife he was so proud of, the first thing he’d bought for himself with his own money. My father had worked from the time he was a child, and others always needed the money he earned more than he did—his widowed mother Rachela Goldman, his younger brother Henryk Goldman, and his baby brother David.

That pocketknife was the height of sophistication. A remarkable tool that I found endlessly magical. The most wonderful in the world. Countless parts popped out of it.

Some of them had functions the world had never known.

From the time she was a child, my mother suffered from problems with her teeth, which got much worse when she was a pioneer in Palestine. She immigrated there with members of the Hashomer Hatsair youth movement. She paved roads and lived in Kibbutz Mishmar Haemek and Kibbutz Beit Alfa until she had to abandon the man she loved, Avreim’ele, along with her ideals and her girlfriends Clara and Ziga, because she had to go back to Poland to recover from a terrible fever she’d caught, and because her sensitive, almost transparent alabaster skin and her gorgeous Titian red hair could not survive the deathtrap of the Mediterranean climate.

Her good health was restored in Poland, but the teeth she’d lost in Palestine weren’t, and her older brother, Leibek Gruber, who’d been to dental school in Berlin—or was it Vienna—made gold bridges and crowns for her. The Germans murdered Leibek.

In Krakow, after the war, a dentist who had gone to dental school with Leibek pulled out the miserable stumps left in my mother’s mouth and made false teeth for her. That dentist was my worst nightmare, even worse than the Spanish Inquisition I’d read about in books—but that was after the war, before we immigrated to Palestine.

The gold of the crowns and bridges Uncle Leibek had made for my mother was given to Hania Seremet, and that gold bought me a few more weeks in the village, in the fresh air, the wide open spaces, the sunlight, on the side of life, the Aryan side. My good health, my tan, my apple-red cheeks, my bruised knuckles, the hard skin on the bottoms of my feet—all those disappeared in a flash in my parents’ hiding place.

The lice remained.

I don’t like all this digging up of the past.

I ABSOLUTELY DID NOT WANT TO BE THERE WITH MY MOTHER and father, two people I didn’t remember, almost strangers, whom I didn’t like at all.

My mother began asking me all sorts of questions; she asked, asked, and asked. I didn’t understand her language. I’d forgotten. They didn’t understand me. I’d come back speaking a dialect, a rural language in which every sentence ended with a mew of surprise: ta-ee-ou!!!

I wasn’t much of a talker anyway, and I only answered questions when I had no choice.

My mother took a few small, damp rags and began wiping me all over, even inside my ears, even behind my ears, even between my toes. My cute little toes, my family. Fat father big toe, mother middle toe, and their three children: two slightly bigger children and a sweet baby—my little toe.

Those pink toes were like little birds. On the underside of each one was a small bump, like a tiny beak. Sometimes, when I had something to draw with, I drew little faces on my toenails. I liked to draw them on my palms too, and then distort them to give them funny expressions.

But when I saw the row of blue numbers on Uncle Isser Laufer’s arm—he always wore a hat, and under it a kind of upside-down saucer made of soft velvet—I immediately stopped drawing on my body.

I saw.

I saw it, that row of numbers, when Uncle Isser Laufer rolled up his sleeve and wound a strip of black leather around his arm and attached a black box to his forehead, then wrapped a striped white shawl around his shoulders and swayed forward and back and sideways so strangely, not exactly a respectable way for a grown-up to behave, as he mumbled and made strange sounds.

Unlike the drawings I drew on my toenails and palms, the numbers drawn on Uncle Isser Laufer’s arm couldn’t be erased, even after he washed it. They were there forever. And from then on, I never drew anything on my skin or body again.

That was when there was no more war in the world and my mother and father and I lived in a room in an apartment with other people and my mother kept saying, saying, and saying that without her, we all would have been destroyed. She was right. All sorts of people began visiting us then. Uncle Isser Laufer also appeared suddenly and lived with us for a while. My mother said that before the war, he had a family, a wife and a child, but now it was just him. And the people who came, ugly, gray, tired, and sad, had those numbers. They would roll up their sleeves and show them to my mother and father.

I didn’t look, but I saw. And they told us. They told us everything. Unbelievable stories that happened in the world. I didn’t look, but I saw. I didn’t listen, but I heard.

I hated all those ugly people. Uncle Isser Laufer was the only one I liked. I loved to breathe the smell that came from him, a sad, lovely smell, like the fragrance of lilacs.

My mother scrubbed and wiped my whole body with the damp rags. It wasn’t very pleasant, being with those two people I didn’t know, didn’t remember, didn’t understand, who were shocked and amazed by me, who were so excited to see me, who tried to wash and clean and fix me. I felt as if something was very wrong with me.

I didn’t want to be there.

When the dirt that had accumulated on my body during all those months in the village—in the pigpen, in the straw-lined coffin I slept in—when all that dirt had been wiped away, the lice had their turn. And it was wonderful.

My mother spread a newspaper on a chair, bent my head so that my hair streamed downward, and began combing it with a fine-tooth comb. It hurt at first. My hair was full of knots. But at some point, the lice started to fall out. A shower of lice fell onto the newspaper, thousands of lice, millions, and every time a louse fell onto the newspaper it made a gentle tapping sound. A shower of taps. After a while, the shower thinned out—the time between taps grew longer and longer—until the tapping stopped altogether. And no more lice fell out. I watched the entire time, entranced by the creatures that rustled on the newspaper right under my nose and eyes.

When the shower of lice died away, my mother folded the newspaper that was teeming with life and went inside the apartment to the part where the Juzaks lived—of course, only after checking that the coast was clear—and threw the folded newspaper with millions of my lice into the opening of the oven under the gas range in Mrs. Rozalia Juzakowa’s kitchen.

The lice burned silently.

Having my hair combed with a fine-tooth comb became a daily ritual. I enjoyed it very much.

I liked the closeness to my mother, who under different circumstances had not volunteered hugs, kisses, and stroking, and I liked the temporary and surprising relief from my itching head, but mainly I liked the reading.

I’VE ALWAYS KNOWN HOW TO READ. I KNOW HOW TO READ because of the lice.

While my mother spread the newspaper and combed the hair on my bent head, I looked at the black marks on the paper. I quickly learned to distinguish the ones that moved, running every which way, from the ones that remained quiet and orderly in their places.

Those weren’t the lice, they were letters.

There were pictures too. To see them properly, I sometimes had to turn the paper around. That’s how I realized that the letters—like the pictures—had a direction. They didn’t stand on their heads or lie on their sides or decide suddenly to turn over and walk away. The lice, on the other hand, used to dart back and forth in total chaos.

I assume that my mother and father helped me distinguish between the scurrying lice and the inanimate shapes, and taught me how to decipher their meanings. They must have, because I knew how to read. I’ve always known how to read, and reading kept me sane.

The Red Army and Batiushka Tovarish Stalin saved my life, and books saved me from life.

I’ve always read, everything, every word: captions in the newspaper, headlines, articles, advertisements. I even read the four-volume Encyclopedia of Sexual Knowledge that survived from the Jewish gynecologist’s library. Later, when we were liberated and we could come out of our hiding place and walk on the side of life, the Aryan side, I found that while my legs had forgotten how to walk, and I could talk only sparingly and in a thin whisper, I had no problem reading—reading signs, placards, graffiti, reading everything: what was written on bus tickets, on matchboxes, on cigarette packs, on labels, in books.

Books, those wonderful books. Those colossal heroes—Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens, Romain Rolland, Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, Kipling…. A terrible fear crept into my heart: Would there be enough books?

But there were, and there continued to be. They didn’t stop.

Later on, they waited for me in libraries. Bound and rebound, again and again. Sometimes a careless bookbinder would distractedly slice off the edges of the pages, lopping off a bit of the body of the text. Then I had to guess at the beginnings or ends of the words that were missing.

And the smell. The smell of the books. The yellowing, crumbling pages spotted with oddly shaped stains, their corners folded into donkey’s ears. Signposts left by those who had read them before me.

I loved them too, my brothers in reading, my brothers in spirit.

They were here before me.

Here’s a note between the lines written in an educated handwriting. Here’s a stain. Coffee? Or maybe fine, expensive cognac? Or maybe absinthe, a greenish poison the color of celadon, the color of the dress with the satin flowers my mother embroidered and sent me when I was in the village, the color of my reading robe, the color of the expensive varnish of our new furniture in Krakow, the color of my father’s Skoda after the war. Like the green in Picasso’s paintings. Our Picasso. He loved Tovarish Stalin too, and he even painted him—a strange painting.

Cosette of Les Misérables, the gracious Little Lord, Tom Sawyer, Tom Thumb, Emil and all the detectives, Mowgli and Bagheera the black panther, Jean-Christophe, David Copperfield, d’Artagnan, David of The House of Thibault and Sergei from Ilya Ehrenburg’s The Storm, Levin and Pierre, blue-eyed Prince Myshkin, and the brave Oliver Twist.

Thank you all, my heroes.

You are the teachers I never had.

What a terrible shame that I didn’t have a teacher.

Thank you all for the worlds you created for me, that opened up for me when I needed them so badly. Those were my real worlds. That was my chosen reality. I would not have survived if they hadn’t been my parallel existence.

THE HEAD LICE, THE ONES THAT DARTED BACK AND FORTH and the ones that didn’t move, weren’t the most dangerous lice.

The other kind was the most dangerous, the kind that frightened my mother—the clothes lice. The lice that caused typhus. They were much harder to get rid of. They hide in the seams, and my mother and father spent long hours running their fingers along the seams of the rags that were our clothes. When they found a louse, its fate was sealed—to be crushed between two fingernails.

Along with the crushing came a soft popping sound that brought an expression of deep satisfaction to my parents’ faces. Hunting for clothes lice also became a ritual, and like the hunt for head lice, a Sisyphean ritual.

My father and mother carried out that never-ending ritual of hunting for clothes lice with an air of quiet, almost idyllic calm.

It was always quiet; after all, we couldn’t let anyone on the other side, the Aryan side, the side of life, know that Jews were hiding there.

For us, the side of life was the side of death.

I thought that’s how it was in the world.

Sometimes, while the hunt for clothes lice was going on, my father would tell me stories. And so, to the soft popping sound of lice being crushed between fingernails, I heard for the first time about the heavens and the earth, the void, the sun, the moon and the stars, the plants and the animals. I knew all about the plants and animals from my time in the village. And I heard about the snake and about Adam and Eve, the confusion of Babel, and the man who gathered all the animals and put them into an ark right before the enormous rains fell from the sky and flooded the whole world.

That ark was their hiding place because outside of it was the side of death, just as it was with us. But that man had prepared a great deal of food. Each animal had the kind of food it liked, and there was enough for all of them. They weren’t hungry, and the horses could neigh, the cows could moo, the birds could sing and chirp. We couldn’t. If someone outside heard us neighing or chirping, that would be the end of us and of the Juzaks too. We had to whisper, to whisper very, very quietly.

I could smell the fresh fragrance of wood in the ark that man, Noah, built. Juzef Juzak was a carpenter too, and our hiding place, which was disguised as his carpentry shop, had the same pleasant smell of wood splinters, not like the rotting wood smell of the coffin I slept in back in the village, not like the varnish smell of the closet I hid in with my father when the Gestapo searched our hiding place.

Then, in my father’s story, the rain stopped and the rainbow appeared.

The rainbow, my rainbow.

The man with the ark and all the animals were saved, they remained alive, and we too were alive in our ark.

By we, I mean my mother, my father, and I, my two beloved mice, Mysia and Tysia—who hadn’t yet run away because the Red Army still hadn’t begun its heavy bombing—and the millions of head and clothes lice.

The most wonderful stories of all were the ones about the children of light.

We never spoke the word “Jew.” The word “Jew” was equivalent to the word “death.”

There were stories mocking the evil pharaoh of Egypt—how much I loved reading, after the war, Mika Waltari’s Sinuhe the Egyptian and Boleslaw Prus’s novel, Pharaoh. There was the story about the sea splitting apart. And then there was the most marvelous story of all—the story about manna falling from the heavens.

Father told me in a whisper—after all, we couldn’t let anyone from outside know that the children of light were hiding here—that manna is a kind of cotton that you put in your mouth and eat, and it tastes exactly like the food you love the most, even cherries, for example.

My father also told me about the good soldier Schweik. My father loved that good soldier all his life. He always kept the book, with Lada’s beautiful illustrations, next to his bed before the war and after it, but he didn’t have it in the hiding place. He recited whole chapters to me that he knew by heart.

Sometimes my mother told me stories too. About elves in pointed red hats who lived in the forest, drank nectar from bellflowers, and helped Marisia, the little orphan. Sometimes the elves were mischievous and played pranks on people. They lived in lovely white-spotted red mushrooms.

And there were stories about fairies, good fairies and naughty fairies—nymphs who combed their golden hair and seduced sailors. That story was in rhyme. And I’d dictate stories to my father about fairies, flowers, princes, and elves.

My mother never told me stories about witches.

In my parents’ hiding place, where I was hiding too, I wasn’t hiding from the Germans at first, but from Rozalia Juzakowa and Juzef Juzak, who had agreed to hide my mother and father, but on one condition: that they come without the girl. Without me. No elves lived there. No fairies lived there. Just the smell of sawdust that was like the smell of the ark, but there was no manna.

My two gray mice, which my father and I trained, were there.

I believe in elves and mice.

Rozalia Juzakowa, a devout Russian Orthodox Ukrainian, believed that lice came from troubles.

Living people have troubles. The lice only lived on living people. If someone had lice, that was a sign that he was alive, a sign that he had troubles.

For the time being, we were alive. Dead people had no troubles and no lice.

We managed not to get typhus. But the Koch bacillus, the lethal tuberculosis bacillus, settled in my mother’s lungs and gnawed a damp hole in them the size of a large plum.

A hole that almost sucked her into death.

MANY ANIMALS PLAYED A PART IN MY LIFE. THE FIRST WAS A white rabbit as soft as a Parisian courtesan’s powder puff. An illiterate farmer from the area brought it to my father as a thank-you gift after my father wrote a letter to the city offices for him.

My father was flooded with requests from good people who were poor and illiterate. He never refused anyone. They would come after working hours, work-weary people, exhausted and smelly, who sat on the bench in front of my father’s office, abashed, rubbing their palms around their hats, which they held between their knees.

Sometimes they didn’t have shoes and were barefoot. The bottoms of their feet were tough—black, thick, and cracked. When they did have shoes, they would leave muddy prints that dried and crumbled on the shiny, polished parquet. Even the ones who had shoes would tie the shoelaces together and hang the shoes on their shoulder when they went out. Those were people who were born barefoot and walked barefoot.

That’s what my mother told me, told me, and told me.

My mother thought they were disgusting. She was always angry that they stole time from my father, the time he devoted to all those bewildered, downtrodden, and barefoot people, work-weary farmers and laborers.

My father was a Communist who believed the world could be changed for the better. My mother was a Communist too, but she was a salon Communist—although even she was once imprisoned for her beliefs.

When his workday was over, my father would read to the ignorant farmers and laborers the letters they had received from overseas, from relatives as poor and wretched as they were who had emigrated in search of a decent livelihood, and he would write the answers they dictated to him in simple words punctuated by tears and longing. My father also helped them when they got into trouble with the authorities and the law.

One of those people who my father helped was Juzef Juzak, the carpenter and alcoholic. The grateful Juzef Juzak thought my father was a saint. We owe our lives to him. It was Juzef Juzak who offered to hide my parents in his house when the Lvov Ghetto was due to be liquidated.

He offered to hide them because he remembered my father’s generosity and he did so over the objections of his wife, Rozalia Juzakowa, the devout Russian Orthodox Ukrainian. Like us, he had followed her to Lvov, escaping with his daughter Ania and his sweet little boy, Edjo. Juzak hid my mother and father in a room disguised as a carpentry shop, but only on one condition: that they come without the girl.

I’m the girl.

In the end, I hid there too, and my life was also saved because of him.

At the end of the war, when Batiushka Tovarish Stalin and the Red Army saved us and captured Berlin, when Communism began to build a new world, a just, good, and beautiful world, when my father, as a loyal party member, was given an extremely important job and once again was in a position to help Juzef Juzak and his family, he brought them with us to Krakow and helped him find housing and work. The Juzak family was smaller then. Teenaged Ania had already died of tuberculosis in my mother’s arms. My mother had caught the disease, and barely, miraculously, came back to life after the war.

The white rabbit that was as soft as a Parisian courtesan’s powder puff suffered a black fate. My mother said that I almost suffocated it with love. I was a year and a half old. They had to pull it out of my little arms, which clutched it as tightly as they could, and return it to the grateful man, that illiterate farmer.

The farmer and his family made a pie out of the rabbit and ate it.

My mother was honored with a gift of one of the dead, devoured little powder-puff rabbit’s soft, adorable white feet, for luck.

My mother threw the poor foot in the garbage.

The long-haired, soft white cat in the yard played with the rabbit’s foot, and dashing around with the foot in its mouth it looked like a fantastical mythological creature with five feet, four regular ones and one that grew from its mouth instead of a tongue. Later, when the Germans invaded and shells were exploding and we ran away on a freight wagon harnessed to a workhorse that had enormous brown hindquarters with white spots, the gypsy woman’s prediction came true—everything we left behind was lost.

Even the white rabbit’s foot in the white cat’s mouth.

That’s what my mother told me, told me, and told me.

We traveled at night and hid in barns and stables during the day. I wasn’t teeming with lice yet. Lice are animals too. The lice were with me all through the war and later too, when the war was no longer in the world. I used to bring them from orphanages, from schools and summer camps.

Except for the fact that we went there in the summer, those damn camps were just like the orphanages.

I also brought lice from the camp for Jewish children in Zakopane. They shot at us in Zakopane. The Poles shot at us, not the Germans, and that was after the war was no longer in the world. They attacked the villa at night and shot at us.

They weren’t Germans. They were Poles who didn’t like Jews. Not even young Jewish children. They were against the Jews.

Anti-Semitic means being against the Jews, that’s what my father said. They want to kill the Jews that the Germans hadn’t managed to kill. He wasn’t worried, not then. He said it was only a matter of education. They’ll learn, those Polish anti-Semites, and understand that there’s no difference between people and everyone should work according to his ability and receive according to his needs. That’s what my father, who was a Communist, believed. And those Poles, those anti-Semites, hated not only the Jews, but the Communists too. They hated the Russians, who liberated them from the Germans.

The Red Army, the Communists, saved our lives, but there were Poles who treated the Russian Communists as if they were invaders.

That’s what my father, who believed that everything would be better, explained to me. And he continued to believe it until the Communists arrested his best friend and the anti-Semitic Poles threatened his life.

WHEN THE WAR BROKE OUT, I GOT TO KNOW MANY LIVING creatures that weren’t people. The squat, plump rats in the ghetto, for example, that the skinny, stiff-haired cats bolted from in fear. Do I remember that?

Or maybe I remember the rats, like the powder-puff rabbit, only from stories?

When the war broke out, I also got to know many bugs and other small creatures. Spiders and the wonderful masterpieces they spun, their webs. Shiny beetles, clumsy and slow. Roaches that ran away when the light was turned on, each at a different speed. Fleas and bedbugs. And of course, lice. The fleas were very hard to see—tiny, jumping dots that bit. I thought the fleas were terribly smelly. But maybe it was the bedbugs that stank?

Those were the animals I knew in the ghetto. But when Hania Seremet smuggled me out of the ghetto and took me to the village of Marcinkowice, to her parents—or maybe they were her grandparents—I met new animals, much larger and more exciting.

The biggest of all was the horse. I’d already seen a horse—the clumsy horse that had big brown hindquarters with white spots that was harnessed to the wagon we rode on to escape from the Germans.

But the horse in the village was my horse.

Everything about my horse was beautiful.

A thick, strong, massive creature. He was gigantic. Later, I thought he resembled the grand piano that belonged to Madame Halina Czerny-Stefanska, winner of the Chopin Competition prize.

In Krakow, when war was no longer in the world, Madame Czerny-Stefanska determined my fate in three minutes by stating that I would never know how to play the piano, and it was doubtful that I would ever know anything at all. The grand piano was black and shiny. The horse was slightly less black, slightly more brown. He was a beast of burden. He stood on four legs that grew from the bottom part of his body, one pair in front, the other pair in back. I never saw the horse lie down. His legs, relative to his body, were thin. At the ends of them were hooves nailed on by the blacksmith, a sunken-chested man who died of tuberculosis a month before Grandfather Seret died.

The horse’s enormous head was very high and grew out of a stiff, arched neck. A rather sparse mane also grew from the neck.

You had to climb a tree in order to see the horse’s back. When he bent his huge head, you could get a peek at his damp, black eye. He had another eye on the other side. You could see his flaring, quivering nostrils and imagine their softness.

How soft and pleasant to the touch that horse’s mouth was. Sometimes I saw his teeth. So huge, so yellow. Long scraggly hair grew out of his quivering nostrils. Once, when I reached out and touched his lips, the sensation at the tips of my fingers was just like I’d imagined it would be, just as I’d always hoped it would be. His pointed ears twitched abruptly every once in a while, alert to every sound.

At the back end of his body was a tail that swung and whipped and drove away the buzzing green flies. Sometimes the horse whinnied, a happy, funny sound. There were always some sores on one of his forelegs and on his gigantic round hindquarters. The humming green flies loved those moist, open sores and would gather on them.

I loved everything about that horse: his smell, the steam that came from his skin and nostrils, even the smell of the dung that dropped out of the hole under his tail.

The birds and beetles loved the dung too.

The little birds would hop around on it and peck at it, and the especially beautiful, shiny purple and yellow beetles would climb onto it. There was another small and roundish kind of beetle, bright red with black dots, that wasn’t at all frightening. It was so lovely, so innocent. I used to put my finger close to the blade of grass it was walking on and it would climb onto my finger and keep walking, tickling it gently. I was cautious and watchful, and when the beetle approached the tip of my finger, I would immediately offer it an additional path to walk on in the form of another finger. If it didn’t have a path like that, the little beetle would eject a pair of fluttery wings from under its wonderful armor, spread them, and fly off. That was a biedronka, a ladybug.

My horse didn’t gallop, didn’t trot, didn’t skip, and didn’t jump. Hitched to the plow, he plowed the field; hitched to the wagon, he transported the sky-high piles of hay. When he wasn’t working, he grazed in the small pasture, his forelegs tied so he could only take small steps.

I was that horse’s shepherd.

That was my job, to watch the horse and make sure it didn’t get into the neighbor’s vegetable garden or cabbage, carrot, or lettuce patches. It must have been summer.

During those bright days when I, Irena Seremet, a Polish Christian girl, shepherded my horse, I would lie on the grass searching the sky for clouds that looked like horses. And there were many horses in the clouds: they galloped, flew, skipped, and jumped. Those were good days.

I pulled carrots from the neighbors’ fields, sweet, stolen, orange carrots for myself and my horse. I tasted the grass that the horse ate.

The bottom part of the blades of grass was light-colored, soft and sweet. And there were bad blades of grass, sharp as knives. The sweetest of all were the carrots, with their heads of wild, mischievous, leafy hair. And there was clover, with its modest sweet flowers, three small leaves on a slender stem. Would I find a four-leaf clover, for luck?

And there were flowers. Flowers and butterflies.

There were pimpernels, with their hundred pink-edged white petals. You could pull them off, one by one by one, yes-no-yes-no, and guess your future. And there were purple lupines and bellflowers that the fairies used for hats. And at the far end of the field, in the damp muddy earth, little blue flowers that winked with a thousand yellow eyes, pleading: forget-me-not. And there were stinging nettles, the nastiest of all the plants.

My mother told me how I described to her and my father how I pulled carrots from the neighbor’s field, shook the dirt off them, and wolfed them down. The stories I told helped my parents understand why I looked so healthy, why my cheeks were as red and shiny “as two apples.”

I also told them about the fascinating guests who occasionally came to visit.

The cheerful knife grinder who was always humming lively songs that ended with a thundering cry of “Hoo-hah!” He had a huge wheel connected by a strap to a lever, and he would hold the knife and press the lever with his foot to turn the wheel, and sparks would spew from under the knife to the rhythm of the songs—like the sparks that sprayed from between the wheels of the tram and the tracks it was speeding along on.

And there was a man who fixed pots, armed with spools of iron wire, who would put together the pieces of a broken clay pot with a skillfully made net and make it usable again, even more beautiful than a new one. They would hang the pot out to dry upside down on the fence posts and it looked to me like a person’s head.

I told them about the croaking, leaping frog and the storks that would drive the frogs out of their hiding place, the storks that traipsed around on their long, thin, red legs in the muddy corner of the field where blue forget-me-nots with winking yellow eyes grew.

My dear, sweet pigs also loved that corner, the mud corner.

The storks lived in a giant nest they’d built in the top of the church tower. The nest was woven around a broken wagon wheel the farmers had put there for the storks years ago. The farmers loved the storks because they brought luck and babies.

They said that the storks came back to their nest in the top of the church tower every year. The chiming bells didn’t seem to bother them. And that’s where they grew their huge chicks. They would make tapping sounds with their long, sharp, red beaks whenever I came to church for one of the plates of thick, gray, boiling pea soup and potatoes they gave out to the poor in the soup kitchen next door to the priest’s kitchen.

They would spoon out the soup with an enormous ladle covered with congealed soup drippings, and so, with the help of the ladle, the soup passed from the steaming vat to my pot with the broken handle. More than once, the soup splashed onto my hand and burned me.

And on the way to Grandfather and Grandmother Seremet’s house, no matter how careful I was, the sticky, boiling soup would spill and scorch my hands, adding burns to the sores on my knuckles—the sores from the sharp, rusty grater I grated potatoes on.

When the soup cooled, it turned into viscous, greenish-gray glue. And it had quite enough time to cool, because it wasn’t a short walk. I went along paths that crossed wheat fields, and the spikes were taller than I was. Flowers grew there too, red poppies and blazing blue cornflowers.

It must all have happened in summer.

Of all the animals in the village of Marcinkowice, the geese were the stupidest.

It wasn’t a large flock, and I was their shepherd. I was the horse’s shepherd too, but the two jobs were totally unalike. The geese followed each other, waddling along heavily, shifting the weight of their round, plump, white-feathered bodies, from one short orange leg to the other, jerking their long, narrow necks forward, back, forward, and jiggling their rear ends right, left, right. Ridiculous.

When one of the geese—usually an enormous goose, their king—opened its flat orange beak and started honking, they would all go on a terrible, never-ending quacking spree. Later on, when I was twelve and a half, I met the wise Martin, Nils Holgersson’s goose. He wasn’t anything like my geese, which were stupid, malicious birds. I learned about Nils Holgersson and Martin the goose from Selma Lagerlöf in the beautiful, thick book illustrated by Jan Marcin Szancer. My mother gave me the book as a gift on the eve of our emigration from Poland to Palestine, with this dedication:

To My Daughter Ilonka

I give you this book along with a request and a demand that in this new stage of our lives, you become more disciplined and more serious in your attitude toward being independent.

Mother 12.12.1949

What did she want from my life?

And I was such a good girl. I always ironed all the laundry, even my father’s handkerchiefs.

More than once, the leader of the geese, the enormous gander, would chase me and manage to nip my ankles painfully. Bad, stupid animals.

I liked shepherding my dear horse better. He was such a noble horse.

Ewunia Lipska, a small girl my age, bouncy and full of happy energy, who had been hidden in the village as a Christian child, like me—she looked the part better because she was blond—once told me how they made her work at force-feeding geese. Long hours. Day after long day. She told me that geese had a very hard bump in their beaks that bruised your hand when you force-fed them and made it bleed. And the bruise on her hand, which never had time to heal, left a scar.

We only talked about that once, and she showed me the scar.

That was in camp, the summer camp for Jewish children, not in the mountains, not in Zakopane, where the Poles shot at us, but on the shore of the gray Baltic Sea. There were four of us there, all twelve-year-old girls—Clara, Celinka, Ewunia, and me.

One morning, Celinka’s bed and her nightgown were covered in blood. Celinka went into shock. We were all shocked. The blood was coming from her body. From between her legs. I knew that there was such a thing in the world. Would blood come from between my legs too?

It did. On a gray day, December 31, 1949, on the deck, slippery with vomit, of the disgusting immigrants’ ship, Galila.

I’m still a girl. And I see and I am invisible.

I see a dark mountain taking shape in the fog, a golden dome in its center. But Flavius Josephus wrote that the Romans had burned down the Jews’ Temple in Palestine.

I am surrounded by drab, tired, and smelly people.

We’re here.

I want to go back.

THERE WERE ALSO OTHER KINDS OF BIRDS IN THE VILLAGE of Marcinkowice. Chickens, for instance, which weren’t much smarter than the geese. They wandered around everywhere, in the yard, in the house, trying to take off and fly, landing heavily—on the table, on the bed, on the shelf under the holy picture: sweet pink Jezusik, Jesus, his face encircled by a wavy blond beard, his eyes looking skyward, a crown of thorns on his head. Beautiful red beads of blood dripped from where the thorns pierced his forehead.

With his delicate hands, he held open his shirt and the flesh of his chest, and his bright crimson heart glowed and beat inside his body. Yellow flames spouted from it.

The chickens ran around outside in the yard too, foraging, cackling, and pecking.

One even swallowed the most beautiful stone in my collection right in front of me. They would pull up long, pink earthworms, tear them into a few writhing pieces, and eat them. And they pecked everything, all the time, pecked and ate even the snippets of lung Grandpa Seremet spit up after every coughing fit, until he died of tuberculosis.

They had red combs and shiny feathers that were brown, yellow, green, and purple, like the colors of the beetles.

The rooster had a huge comb, a gorgeous tail, and yellow feet with very sharp nails. The rooster walked slowly, pecking the sand aristocratically, proudly, arrogantly.

The chickens had a blank look.

The goats had an even blanker look. A yellow eye with a black rectangle. I didn’t like the goats. I loved the pigs. Pink, plump, round. Sometimes their stubbly skin had strangely shaped dark spots painted on it. Then, I wasn’t yet familiar with the pungent odor of a pig’s skin after it’s killed or it dies and they make a schoolbag out of it or a suitcase you take with you on a stormy sea voyage to Palestine.

Their sweet little faces, with their flat pug noses and round, wide nostrils that looked at me like a pair of eyes that always seemed to express amused understanding. Their curly tails were especially merry. I didn’t like their ears. They were flawed. All sorts of shapes had been cut out of them. The pigs were my best friends. They would make snorting sounds, and I’d answer them. We talked.

The pigs lived in a pen. The pen had a low door, and only a little girl like me, about six years old, could crawl inside. I spent many happy hours in that pigpen, on the straw that was sometimes fresh but usually damp, packed tightly and probably smelly. I loved straw. The coffin I slept in was lined with straw too. The pigpen was my hiding place, my most private place, and the pigs were my best friends. I thought that’s how it was in the world.

I used to crawl inside and sit down in a corner. It was a small place, just a corner in the dark illuminated only by the dim light that came from outside. The darkness was pleasant. The pigs came and went around me, and I played with my doll.

A doll I made myself.

A stick that I found, not too long and not too thin, was the doll’s body. An apple I stuck the tip of the stick into was the head. The little face was made up of dark pea eyes I pressed onto the skin of the apple, a white pea nose, and a piece of carrot or a petal from a red flower was the mouth. Later, when I was already in my parents’ hiding place, after Hania Seremet threw me out of the village because my parents didn’t have any more money to pay for me, I pasted some red flower petals on myself too, from the flowers my mother brought when she went out hunting for bread.

We were very hungry, we had no manna. My mother went out to the Aryan side, the side of life, the side of death. The red flower in the pot was her disguise. Walking around with the flowerpot in her hand, she wasn’t a hungry Jew coming out of hiding to feed her beloved husband and her hungry child, but just another woman who’d bought a red flower in a flowerpot and was walking innocently down the street.

My mother brought the red flower with the bread.

I wrapped a rag around the stick, which was the doll’s body, and my doll had a dress. She had hair too. Sometimes it was bits of yellow straw that I stuck into the apple skull, and sometimes it was marvelous corn silk—long, soft, shiny greenish hair like the hair of the water nymphs my mother told me about when were in the hiding place, the nymph sitting on a rock, combing her hair and seducing sailors. My doll was so wonderful—my dolls, actually, since I had many, because of the pigs.

That was the only conflict I had with my friends the pigs. When I had to leave the pigpen, I hid the doll deep down under the straw in the corner and the nosy pigs would always find it and gobble up the apple head. And again I had to put a new head on my doll. But that wasn’t so bad; there were always enough apples, peas, and straw. My friendship with the pigs was more important. It was their nature to be likable, voracious gluttons.

No friendship developed between me and the cow. The cow was skinny and brown, and she might have had tuberculosis. Maybe Grandpa Seremet, who spit up his lungs, had caught it from her. And maybe I caught it then too, but instead of getting sick and dying quietly, I developed an immunity that later saved my life when I was in the hiding place with my mother and father.

The cow and I were neighbors.

The szlufan, the piece of furniture that was a bench by day and a bed by night, a kind of coffin, was lined with the same straw that lined the cowshed, and the same mice scurried between the cow’s legs and over my body. Then, in the village, I didn’t yet know what wonderful animals mice were. I trained my gray mice, Mysia and Tysia, later on, when I was in the hiding place with my mother and father—until they left us when the Red Army, which saved our lives, began its heavy bombing and volleys of katyushas.

But already then, in the village, I liked the mice. They were my nocturnal friends.

The village mice scurried around in the cow’s straw and in the straw of my coffin. The cow and I had the same smell.

When Grandma Seremet milked the cow, sitting bent over more than usual on a round stool with three fat legs and pulling on the pink udders, the stream of milk would strike the sides of the tin pail and the smell was white, warm, and pure. It spread, filling the air and overcoming all the other smells—the smell of the fleas, the smell of the mice, the stench of urine, excrement, and dung. The smell of the milk blended with other, more pleasant smells, like the aroma of the straw, the green fragrance of clover, or the smell of sawdust. It wasn’t a sad smell like the scent of lilac would be in the future.

Luckily, the hiding place Hania Seremet dumped me into, my parents’ hiding place, had a nice smell, the smell of sawdust. After all, the room was disguised as Juzef Juzak’s carpentry shop.

When Grandma Seremet sat on the stool and milked the cow, unruly hairpins from her sparse bun of hair would drop into the pail, and she would fly into a rage. But when the hairpins didn’t fall out, and she was in a good mood, Grandma Seremet would pour some of the foamy, steaming milk into a small wooden bowl and hand it to me.

The aroma, the taste, the warmth.

Even the ice cream my father bought me from the man with the wagon didn’t taste as wonderful as that milk. That was the first ice cream in my life. It was after Tovarish Stalin and the Red Army liberated us and saved our lives, and my father had to take me from the villa that belonged to the evil, cruel Fishmans because I bothered them. I couldn’t stop crying, and crying was permitted then because they hadn’t killed us and Batiushka Stalin had liberated us. My father took me from the Fishmans’ villa to the orphanage on his way to sell newspapers, while my mother was dying of tuberculosis in the hospital.

I thought that’s how it was in the world.

EVERY NOW AND THEN, HANIA SEREMET CAME TO THE VILLAGE, the strange woman with the white face and the clenched jaw who took me out of the ghetto one damp night when I was walking between my mother and father as plump, squat rats scampered along the walls in the opposite direction.

Hania Seremet would order me to draw on the pieces of paper she brought me. After only drawing in the sand with a stick or on the walls of the pigpen with a lump of coal, I enjoyed drawing on paper with colored pencils.

Once, Hania Seremet brought me a magnificent satin dress in sweet, light pastel colors, washed me, and combed my hair—the lice were hiding close to the roots—and we went to the photography studio in the nearby town. The studio had an unfamiliar smell and it was dark, like the office of the handsome, sad eye doctor would be in the future.

The photographer stood Hania Seremet and me close together. He touched me and arranged my hands in the pose he wanted.

Hania Seremet was wearing a sweater embroidered with tiny flowers. My mother had embroidered those flowers too, just as she had made my magnificent satin dress. She would sew and embroider in the hiding place and Hania Seremet and Rozalia Juzakowa would sell her work in the market so there’d be a little more money to pay them.

The photographer also took pictures of me alone. He told me to sit this way or that and look here or there.

I never saw the dress again. The pictures exist. Like my drawings, they were proof that I was still alive. Hania Seremet gave the proof to my mother and my father, and they gave Hania Seremet money for hiding me in the village. When the money ran out, they sold the gold bridges and crowns that my father so skillfully pulled out of my mother’s mouth with his magical Swiss pocketknife. When there was no more gold left in my mother’s mouth and the search for the treasure left in my father’s villa failed to uncover anything, Hania Seremet dumped me into my parents’ hiding place, even though Juzef Juzak and his wife Rozalia had not agreed to hide them with their daughter, that is, with me.

And so I continued to hide in the hiding place for a long time.

And just as she threw me out, Hania threw out the beautiful little boy, Daniel.

She dumped me at the hiding place. The beautiful little boy, Daniel, she threw out to die.

Daniel, the beautiful Jewish boy Hania Seremet took out of the ghetto, was my age. His favorite animal was the cow, and he always tried to be there at milking time. When Grandma Seremet wasn’t looking, he’d dip his fingers into the tin pail of steaming milk and lick them. The beautiful boy Daniel stayed in the village with me for a very short time. His parents gave Hania Seremet a great deal of money, jewelry, diamonds, and gold to take him out of the ghetto and hide him in the village. They promised to keep on paying her. They even registered their house in Lvov in her name—just as my father registered the villa in Bochnia in her name—so that if the Germans murdered them and Daniel remained alive, he would have someone. The beautiful boy Daniel’s parents were murdered and Daniel was an orphan. There was no one to keep paying for his life. Hania Seremet took him to the ghetto and left him at the entrance gate, and the Germans murdered him there. Daniel, a beautiful little Jewish boy, had curls and translucent white hands. A long time later, when the war was no longer in the world, I saw Daniel in a painting by Maurycy Gottlieb, who painted many pictures of Jews with shawls on their shoulders and head coverings like the one Uncle Isser Laufer had.

That wasn’t the first or the last time that Hania Seremet, the pretty woman with the white face and clenched jaw, took money from persecuted Jews, then turned them in or left them to die. My mother called her “the murderess.” My parents knew about what she did and about the deals she made with the Jews in the ghetto. They knew she had a lover in the SS who shared her profits.

Hania Seremet threw me out too, but not at the gates of the ghetto. Maybe because there was no more ghetto. The ghetto had already been liquidated. But still, she didn’t throw me into the streets, to sure death. Maybe girls who sleep in coffins don’t die so quickly.

Hania Seremet dumped me into my parents’ hiding place.

My mother said that when she heard about the murder of Daniel’s parents, she wanted to adopt that beautiful boy—if the war ended, of course, and if he remained alive, of course. But there was no more money to pay Hania Seremet. There was no more money to pay for me, either. And the beautiful boy Daniel was murdered like hundreds of thousands of other Jewish children.

I was alive.

I FIRST BECAME ACQUAINTED WITH MY TWO LITTLE GRAY MICE—Mysia and Tysia—in our hiding place at the Juzaks’ house on Panienska Street, in the room disguised as a carpentry shop.

Mysia and Tysia lived in an old black cast-iron stove. The stove was round and had a small door that closed with a hook. The door might have been transparent. Its legs were curved like a lion’s or a tiger’s, or maybe a small dragon’s.

The stove wasn’t in use.

Once, in the past, before I was taken out of the village of Marcinkowice, they used to heat the house by burning books in that stove. The books were taken from the large library that had belonged to the man who owned the apartment before the war—the Jewish gynecologist. A few books from that library survived. They’re in my house. The doctor himself, his mother, wife, two daughters, and baby son were murdered by the Germans. That was at the beginning of the war.

Living in the apartment now were Mrs. Rozalia Juzakowa, Mr. Juzef Juzak, and their son Edward, Edjo, who was my age. Their daughter, Ania, was already dead.

They agreed to hide my father and mother, and later, against their will, me too.

Their daughter Ania died of open tuberculosis in my mother’s arms when she was sixteen, and my mother must have caught it from her. After the Red Army led by Stalin liberated us and saved our lives, my mother was admitted to a tuberculosis hospital in Lvov and almost died because her left lung, or maybe it was the right one, had a damp hole in it the size of a large plum. Professor Ordung saved her life. The hole had been gnawed by the tuberculosis bacillus, the Koch bacillus.

I was the first to hear the rustling of my little gray mice.

I still didn’t know they were mice.

I still didn’t know what color they were.

They still didn’t have names.

And they still weren’t mine.

I don’t know whether I first heard the rustling during the day or at night. Most of the time, both day and night, my mother, my father, and I, and our millions of head lice and clothes lice, lay on the makeshift bed in the right-hand corner of the room among the blankets and pillows and the torn, tattered, threadbare rags.

We had to be very quiet in that hiding place.

We couldn’t walk.

We couldn’t talk.

We couldn’t laugh.

And I didn’t cry.

No one, not a single living soul, could know that we were there. They would report us to the Gestapo and that would be the end of us, and maybe of the Juzak family too, Rozalia, Juzef, and little Edjo. The Germans also killed the people who hid Jews.

We hid in that little room disguised as the carpentry shop where Mr. Juzef Juzak, carpenter and alcoholic, supposedly worked when he came home from his job at the factory.

Since there was no vodka, Juzef drank wood alcohol, suffered from delirium tremens, and had hallucinations filled with hideous white creatures.

My mother was the only one who knew how to calm him down when those horrors attacked him. From inside the apartment, we’d hear screams, curses, the sound of objects smashing and shattering. Rozalia Juzakowa would burst into our hiding place, disheveled, pitiful, weeping and agitated. She’d wring her hands and beg my mother—Pani Goldmanowa, Pani Goldmanowa, please, I beg you. Juzef is having an attack. He’ll kill himself, he’ll kill all of us. Come, please, come right away. You’re the only one who knows how to cure him, to “cool him down,” to restrain him, to soothe him.

And my mother would go.

After a while, the voices would die down and there would be silence. My mother would come back to our bed in the corner, her clothes and hair reeking of machorka, vomit, sour sweat, and vile alcohol.

Juzef Juzak was a good man.

After all, he had agreed to hide my mother and father before the ghetto was liquidated. Without the daughter, of course. I could see why. He didn’t know me. He’d worked in my father’s storehouses in Bochnia before the war. And he hid us for money, of course. He didn’t know we had a lot less money than he thought, but after the war, after we survived, my father took care of the Juzak family. Even after we moved to Palestine, we sent them money. Even during the very hard times in a new and violent country.

Mr. Juzak loved and respected my father. Like us, he’d fled to the east when the Germans took over. His wife, Rozalia, was Ukrainian and had relatives in Lvov. He found work again in Lvov, in the slaughterhouse and tanning factory where my father was chief accountant. That was when the Russians still had control of Lvov following the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact. Juzef Juzak and my father continued working there even under German occupation, after Operation Barbarossa, when the Germans attacked Russia and pushed the Red Army further and further back, winning victory after victory, until Stalingrad.

MY FATHER’S MANAGER DURING THE GERMAN OCCUPATION was a good German. He even let my father bring me and my mother to live in a tiny room next to the slaughterhouse. It was a dream, a paradise compared to where we lived in the ghetto. And food was plentiful too—the entrails and blood of the animals. Herr Knaup—that was the name of the good German manager who helped save our lives by allowing my father to live in that tiny room next to the slaughterhouse.

My father helped save many Jews from hunger by hiding entrails and keeping pails of blood from the slaughterhouse for them. They drank the blood on the spot. The entrails they wrapped around their bodies and smuggled into the ghetto in the hope that the Germans wouldn’t catch them. They were the Jewish workers who left the ghetto in the morning to work in the slaughterhouse and tanning factory and returned to the ghetto at night, bone-weary and crushed, but alive.

One of the Jews who came from the ghetto every day in well-guarded groups to work in the slaughterhouse snuck into our tiny room and begged my mother, even kissed her hands, to keep a plain, not very large wooden box for him “for only a few days.” The box was locked with a key, and it had a flower carved on its cover.

That was very dangerous. My mother didn’t like it. But even so, she did what the man asked. “If I’m not back within a month, the box and what’s in it are yours, Pani Goldmanowa,” he said as he handed it to her.

That’s what my mother told me.

It was already evening. A key hung on a thin string around his neck. He took it off and opened the box.

Light streamed from it.

It was like “open sesame” from the Arabian Nights, my mother said. Jewels, precious stones, diamonds, pearls, gold chains, treasures.

To show how much he trusted my mother, the man left the box open and didn’t relock it with the key.

The man came back two weeks later.

“Pani Goldmanowa, in return for your generosity, please choose what you like best and take it,” the man said. My mother, former member of the Hashomer Hatsair youth movement and pure, modest salon Communist that she was, picked out a small, unpretentious pin: a line of white gold set with a small diamond.

Perhaps if she’d chosen something else, something more valuable, there might have been a little more money to keep me in the village among the living. But that’s how it was.

The man swept the contents of the box into a bag that tied with a string, hung it around his neck, pushed it under his armpit, and left.

He didn’t go back to the ghetto. We’ll never know if he survived or was killed. Maybe they picked him up in an aktion and sent him to the Janowska camp, the way they once caught my father in the street and ran him to the camp where they tortured him on the parade grounds for two days, along with other prisoners, other Jews.

That’s what my mother told me, told me, and told me.

She told me how much she worried, and how she ran out to look for my father and how he finally came back half-dead, filthy and crushed.

That’s how it was.

But my father remained alive, and no one knows what became of that man with the box.

My father promised to pay Juzef Juzak a fortune for hiding him and my mother. There was no fortune. A few weeks before the German invasion, when I was two years old, my father had invested all his money in purchasing a huge quantity—a trainload full—of building materials.

My father had a wholesale building materials business. That was in Bochnia.

The war started, the train loaded with building materials arrived and stopped on the private track leading to my father’s storerooms. The old gypsy woman’s prophecy had come true. My mother, my father, and I, along with Dr. Fishler, a family friend who had performed an abortion on my mother a month earlier, escaped in a wagon harnessed to an enormous workhorse. My mother, as befitted a salon Communist intellectual, condemned uncontrolled reproduction, and like many of her milieu, preferred to have only one child.

She had been carrying twins.

And if they had been born?

EVEN IN THE SILENCE OF THE HIDING PLACE, THE NEW RUSTlings were quiet. I realized very quickly that they were coming from the old iron stove.

It happened when I found my wonderful little figurines nibbled away, the ones I molded from breadcrumbs I’d managed to save from the bread my mother heroically, miraculously brought us from the soda factory manager’s wife. They lived in the neighboring house, on the Aryan side, the side of life, the side of death.

It happened when we’d had nothing to eat for a long time, when the Juzaks went on a trip and left us in the house without food. My mother said that Juzakowa—Juzak, almost always drunk to the point of unconsciousness, was never much of a thinker or planner—wanted to starve us to death so she could finally be rid of us, of that terrible curse, the Jews, who endangered her life and the lives of her husband and little boy, Edjo.

When the war was no longer in the world, Juzakowa told us that Hania Seremet had offered her poison to kill us with.

Only some breadcrumbs were left. I used to mix them with saliva, knead them for hours until the mixture was uniform and smooth, not too moist and not too dry, not too soft and not too hard, but just the right consistency.

My fingers would seek the same consistency from the clay I molded into fancy ballerinas when the war was no longer in the world but I was, and we lived in beautiful Krakow.

In the hiding place, I molded tiny birds.

In the shape of my toes.

I had a marvelous flock of birds.

I hadn’t seen a bird for a long time.

In our hiding place, we weren’t allowed to go near the window, but I remembered the birds from my time in the village. I remembered clearly their shape, the beating of their wings, their chirping and singing.

I arranged the flock of wonderful birds in a splendid row to dry.

I looked at them proudly for hours.

In the morning, the row was in ruins.

The birds were nibbled away. A strange sort of nibbling. One was missing its wings, another its tail. One had lost a wing, another its beak. The bodies of some of the birds had almost completely crumbled, and others had simply vanished.

Scattered among the crumbs of my wonderful, tiny bread birds were small black droppings.

Mice, my mother said.

I was so glad.

I’d known many mice in the village. For whole nights, they scurried around the coffin I slept in, even inside it right on my body. I liked the mice. I liked the horse and the pigs better, but still, I was fond of the mice. They were my nocturnal friends, like the moths, the fireflies, and the owl that lived above the cow, a small owl I didn’t see very much, but I heard his faint voice every night. He flew silently. Hoo … hoo … hoo … that little owl would hoot.

When we trained my dear gray mice, my father told me that owls like to eat mice. How lucky for me that I’d never seen my owl eat any of my mice.

My father told me there was an old proverb that said church mice were extremely poor. Mice hiding with Jews were even poorer, he said.

Until then, I’d never heard the word “Jew,” Zyd in Polish. We never spoke that word. Maybe my father was sorry he’d said it. My mother, who was painstakingly searching the seams of a patched shirt for lice—the dangerous lice, the typhus lice—gave him a piercing stare.

We decided to train the mice, already mine though I still hadn’t seen them. I didn’t even know how many there were, whether there was only one or two or more.

There were two.

We saw them for the first time after lying in wait for days.

We sat very, very quietly. That wasn’t actually very hard to do. We always sat quietly. We waited for them to come out and partake of the wonderful meal I’d prepared especially for them. They didn’t need manna from heaven. They had me.

They were so dear to me that I continued to save precious breadcrumbs for them, mix them with saliva, and knead the mixture for hours. Only when it was uniform and smooth, not too moist and not too dry, not too soft and not too hard, just the perfect consistency, did I mold it into little baskets filled to the brim with Lilliputian treats: miniature apples, tiny rolls, miniscule pears, diminutive wine bottles, and even minute slivers of cheese.

I put those marvelous refreshments at the foot of the old black iron stove, right next to the rounded lion’s feet—or the tiger’s feet, or maybe the baby dragon’s feet—under the slightly open door.

And then it happened, the wonderful thing I’d dreamed of for so long. From the crack of the open door emerged the tip of a sharp little quivering pink nose, twitching gray whiskers, an elongated head that looked at me with shiny black beads, pinkish, transparent ears, tiny legs with long toes, each with a white nail at its tip, and between them, a tiny body rounded into a backside that ended in a glorious tail! A long, narrowing, hairless tail, a flexible, magnificent tail.

It was a mouse.

I immediately gave it the name Mysia. From behind it—how wonderful!—another mouse emerged. I could see right away that the second one had a shorter tail. I called it Tysia.

With endless patience, my father and I trained the little mice.

There were successes and setbacks. We were patient. Time was something we had plenty of. What we didn’t have was food. But I kept on saving crumbs and molding them into treats.

My father and I, with the baskets I’d molded from the breadcrumb mixture, sat very, very quietly, lying in wait for long hours until the little mice appeared at the door of their house—the old black iron stove. At first they would snatch the baskets and scurry off, but they grew more confident with time and would stay longer, move a bit closer, to my father’s shoe, onto his shoe, and finally—how wonderful it was, how exciting!—they’d climb up my father’s leg to his knee. Hooray! The gray mice were mine, they were trained.

We lived in conditions that were perfect for training mice.

After a while, I saw that Mysia was getting rounder and rounder, fatter and fatter.

I wasn’t surprised. After all, she was the one who always came out first and grabbed the food first. She was also the first to be trained. Mysia the glutton.

ONE NIGHT—WHEN THE NIGHTS WERE STILL VERY QUIET, before the Red Army Air Force began its heavy bombing, before the volleys of katyushas began ringing in our ears like the sounds of paradise, the sounds of fierce pride, of joy—I was listening, as I usually did, to the rustling and whispering of my two little mice, when I suddenly seemed to be hearing other, unfamiliar sounds, very soft sounds, a sort of quiet chirping, a subdued murmuring.

Mysia, as usual, the first to come out, was no longer plump. She sat on her hind legs, holding some crumbs from the miniature basket, and I could see tiny, erect, pink nipples on her red stomach.

I knew immediately what had happened.

After all, my pig in the village had given birth too. And she’d had beautiful piglets, soft and pink, with cheery little tails. She had lain on her side, exposing her fat, whitish stomach, and all her many babies pressed up against her, shoving and kicking each other, hitting and butting to get close to one of the nipples and stay there forever.

Mysia had become a mother too, and Tysia a father—and I’d given them both girls’ names! Tysia was actually a boy.

How wonderful. What a marvelous surprise!

Another family was hiding with us.

I wanted so much to know how many mice had been born.

My pig in the village had given birth to a lot of piglets. I didn’t know how to count, but I could see that after a while, fewer babies were left, and I didn’t try to find out how many and why.

My father peered into the nest of my wonderful gray mice and managed to count fifteen tiny babies. My father knew arithmetic. Later, I looked inside too. I could barely see anything. The inside of the stove was dark, the nest was lined with straw probably taken from our mattress, feathers from our tattered pillows, and wool threads from our unraveling blankets. A red thread was interwoven with them, a thread I knew very well, my thread, which had come undone from one of the flowers my mother had embroidered on the beautiful pink vest she’d sent to me with Hania Seremet when I was in the village, and the one who gave me that vest was the one who took it from me and obviously sold it, just as she had sold the green satin dress I’d worn only once, when I had my picture taken, proof that I was alive.

I loved that red thread. It was one of my treasures, along with some beautiful stones, a little red rag with white polka dots, and a pine cone that gave off the scent of resin. I used to wind the string around my finger, a different one every time, or tie several fingers together with it, carefully, not too tightly. Grandpa Seremet warned me not to cut off my circulation. He spit up and vomited his own blood all the time.

I loved seeing my fingers with the string around them turning red, then pale.

I’d brought the thread with me from the village, and it continued to be an important item in my treasure, along with the picture of a girl with a ribbon—a picture torn from a newspaper that I’d rescued from the latrine in the hiding place. Until one day, the thread disappeared. I was sad about losing it, and puzzled. How could it have vanished from the hiding place that no one ever went in or out of? My mother said that maybe elves took it. Everyone knows that elves are partial to the color red.

My mother was almost right. The thread had been stolen, but it was my wonderful little gray mice that had taken it. I forgave them instantly. I wasn’t angry. In my heart, I gave them the thread as a gift.

The nest inside the stove had a special smell, the smell of rusty iron, vestiges of the smell of burning pages from the Jewish gynecologist’s library, the smell of frayed cloth the mice used to line their nest, and the smell of damp warmth. I wanted so much to touch Mysia and her sweet babies, but I was afraid that mother and babies wouldn’t like that closeness imposed on them, so I controlled myself and pulled my hand back. As it was, I thought it was almost a miracle that the little gray mice let us peek in at their warm family nest.

A few days later, my father looked in at the nest again. He turned around abruptly, and in a characteristic gesture ran his hands over his head, his forehead and eyes, and with unexpected, unfamiliar firmness forbade me to look inside.

I didn’t try to find out how many babies there were this time either, but I didn’t mold any more wonderful baskets brimming with treats from the breadcrumbs I saved. I just left them on the floor at the door to the black iron stove. Something in my heart had changed.

The heavy bombing started. After the first explosion, we no longer heard the rustling and chirping of the mice.

There were no more mice.

Maybe they’d gone down to the shelter when the first siren sounded, the way everyone else did?

We, of course, didn’t go. We were Jews. No one was allowed to know that we existed. If someone found out and informed the Gestapo, that would be the end of us, and before some Communist bomb managed to blow us up, the Germans would murder us. We stayed in our hiding place.

But the small mouse family didn’t stay with us. Apparently they weren’t Jews. Maybe they were Aryans.

We remained alive, we survived the heavy bombing. My mother, my father, and I, and all of our millions of lice. The Red Army came, Tovarish Stalin sent it, liberated us and saved our lives.

And as Batiushka Stalin said in Russian: We shall celebrate in our streets too.

It was summer.

It had finally happened, but it had taken a very long time.

After the heavy bombing that had driven my non-Jewish mice away but not the lice, the mighty German army began to retreat. That was after Stalingrad, of course, and after the Allies finally opened a second front—those imperialists who waited to see whether the Red Army would win or be defeated, until it was victorious at Stalingrad and showed them just who Stalin and the Red Army were.

The Red Army, with the momentum of their great victory at Stalingrad, could have conquered all of Europe, defeated the Germans everywhere, taken Berlin by itself and turned all of Europe into a just place that had no poor, exploited people, a place where everyone worked according to his ability and received according to his needs.

And what if the Red Army had gone on to capture the whole world? Why shouldn’t there be justice in England? In America? In capitalist America that had no justice?

But they were alarmed then, all those capitalists who sucked the blood of the proletariat, and they opened a second front because they were afraid that lofty Communism would sweep them away too and divest them of all their money.

That’s what I thought.

THE GERMANS RETREATED. A DEFEATED, EXHAUSTED, BROKEN army. Soldiers who were thin, tired, and thirsty. Rozalia Juzakowa told us. She saw them. So young, and sometimes so handsome.

She’d bring them water from the house and give it to them when they were lying down for a short rest, leaning against the walls of the buildings. They also leaned against the wall of the house we were hiding in, the house on Panienska Street. Then too, if we had come out of our hiding place, they would have murdered us, even though they were exhausted and drained. You don’t need much strength to murder a sick, almost dying woman, a starving man barely able to walk, and a not-very-big girl.

The German soldiers, members of the superior race. Lying against the wall of the house we were hiding in, their blue eyes were closed, their blond hair messy and scraggly. How many of them were murderers? How many of them were Nazis who followed Hitler happily, as he wrote in Mein Kampf? Mein Kampf was one of the books left from the Jewish gynecologist’s library, and it survived the war with us. Hitler’s eyes in the cover picture have holes in them. Maybe I did that.

Another great war awaited those soldiers. The road to Berlin would be a long one. They left, they were gone.

The German occupation was over.

Silence.

It was over.

We were saved.

Some of the Jews who survived crawled out of their hiding places, out of the burrows and the pits, into the air of the world, and when they did, they were murdered by the Ukrainians and the Poles. They’d survived the entire German occupation and now, right after the liberation, they were murdered.

There were people like that there too. Murderers. And they weren’t even Germans. They were Ukrainians, they were Poles. They really did hate the Jews. They even hated Jewish children.

Or maybe they were afraid that now, after the liberation, those Jews who’d managed not to be murdered would ask the Ukrainians and the Poles to return their businesses, homes, property, everything that had been stolen from them?

As Juzakowa talked and talked and talked, my mother and father listened and were wise enough to wait in the hiding place seven more days. Like the number of days it took to create the world. Only then did they go out into the world that had been newly created for us.

We didn’t know how to walk in the new world. We continued to whisper in the new world. My mother was dying of tuberculosis in the new world. And they dumped me in an orphanage in the new world.