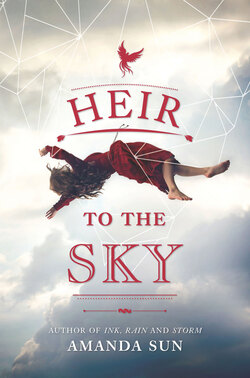

Читать книгу Heir To The Sky - Amanda Sun - Страница 13

ОглавлениеFIVE

“HERE,” ELISHA SAYS, pulling a pair of beige sandals out of her bag. “I grabbed these for you.” She giggles, holding the shoes out to me as she keeps pulling me forward.

“Elisha.” I tug gently against her hand, and we stop in the corridor near the stairway. “Wait. I have to talk to my father.”

She frowns, the shoes resting in her hand against her slacks. “What’s wrong?”

I shake my head. “I’m not sure, but I need to talk to him first. It’s Aban and the lieutenant.”

She nods and helps me slip on the sandals before she follows me to the meeting room. Two guards flank either side of the doorway, tall spears in hand. It’s just a formality, of course. The number of humans left in the world is too small to fear each other.

At least, that’s what I’d thought. The sketch of the Phoenix and the talk of rebellion has shaken everything I thought I knew. I wish the lieutenant hadn’t burned the paper. I need to see what was on it.

I rest my fingers on the cold door handle, and one of the guards turns his head. “Are you looking for the Monarch, Princess?”

“I don’t mind if he’s occupied with the Elders,” I say. “It’s an urgent matter.”

“I’m afraid he’s not in there,” the guard answers as I push in the door to the meeting room, empty and still. “He left fifteen minutes ago, I believe for the village square with the Elders. Some meet-and-greet celebrations.”

My chest feels empty, as though I’m out of breath. Everything feels so wrong, and I can’t explain why. What does it mean that there are two first volumes of the annals? What was dealt with two hundred years ago? And what in ashes is the unrest now in Burumu?

“Thank you,” I tell him, my throat dry, and I turn toward the citadel steps.

Elisha wraps her arms around my arm, leading me into the sunlight outside the great doors. We pass the Phoenix statue, a few stragglers from the celebration still wandering the courtyard. They wave at me, no longer enthralled as I’ve become one of them again. I do my best to smile and wave weakly at them.

“Kali? You’re acting so weird,” Elisha says. “What happened back there?”

“I wish I knew,” I say. “Your uncle lives in Burumu, doesn’t he? Have you heard anything about a rebellion?”

Elisha’s eyes widen with surprise and she shouts, “A rebe—” Then she notices my urgent face and drops her voice down to a whisper. “A rebellion?”

I nod. “The lieutenant and Aban were talking about it. They had some kind of paper being passed around with some big secret on it. Aban had a key around his neck, Elisha, and he brought out this duplicate of the first annal that he could read. The first volume!”

“They have been studying it a long time,” she says. “Maybe they’re finally getting somewhere?”

“No, I mean, he could really read it. The ancient language and everything. I heard him.”

She frowns. “Why would the Elders pretend they can’t read it when they can?”

“I don’t know. And earlier, Jonash told my father there was unrest in Burumu.”

“That’s nothing new,” she says. “You know life is harder there. Work is grueling and there’s little space to live. They all want to move to Ashra. Maybe they’re just exaggerating when they say it’s a rebellion.”

But I’m unconvinced. “Aban was really worried,” I say. “He said something was ‘dealt with’ two hundred years ago. The ink in the first volume was different somehow. The Phoenix looked newer than the rest of the drawing. And there were these rings and some kind of a machine buried in the drawing, under the Phoenix.” I know how crazy I must sound. I can see it on Elisha’s face. But she’s my best friend, and I know she’ll take me seriously, even if she thinks it’s nothing.

We reach the end of the courtyard and start along the dirt path to Ulan. It’s not a long way, and we can already see the tops of thatched roofs and wooden shingles. Folk songs played on goat-string harps and carved flutes float up like a cloud from the town.

“Aban is the most loyal person I know,” Elisha says after a moment. “He’d die for the Monarch and for you. He would.”

“You’re right,” I say, and she is. I can’t help but wonder if my imagination is running away with me, if the pull for escape and adventure isn’t making a bigger deal out of this than it really is.

“They probably just don’t want to worry you, and it will all smooth over. I’m sure there’s a reasonable explanation. Besides, the Elite Guard is based in Burumu. They can deal with problems there. Isn’t that the Sargon’s job? And so what if the drawing in the annals isn’t as old as you thought, or the Elders can read them? What does that have to do with us now?”

I sigh, trying to let go of everything.

Elisha nods as we approach the fountain. It gurgles with cool water filtered down from the lake, and one of the women from the village gathers it up into a mauve clay urn which she rests on her shoulder. She smiles at us, and we smile at her.

“We’re safe now, Kali,” Elisha says. “Monsters can’t reach us this high. Any rebellion will quickly fizzle out when they remember how fortunate we are. We’ve been safe for hundreds of years, and things will continue this way when you’re Monarch, too.” She sidles closer, her voice dropping. “Or is it Jonash that’s on your mind?”

I nudge her away as she giggles. She thinks I’m lucky, and that the whole thing is romantic. She’s bought into the royal distraction like everyone else. “I don’t love him, Elisha.”

She stops giggling and sits on the edge of the fountain, her fingers wrapping around the cool stone. “I’m sorry,” she says. “But you have a whole year to get to know him. Maybe you’ll fall for him.”

I sit beside her, the stone lip of the fountain scratching the pads of my fingers. The trickling water sounds like the gurgle of the waterfall on the edge of Lake Agur, and it fills me with the urge to run there, or to my outcrop on the edge of the continent. “What if I still don’t love him in a year?”

She shrugs. “Then break the engagement.”

I let out a laugh. “My father would kill me.” I dip my fingers into the water and splash her. She winces dramatically as the drops spatter on her cream tunic.

She splashes me back, the water spraying my dress a dark crimson. “He’d come around,” she says. “You’re everything to him.”

She’s right, I know. He would understand if I broke off the engagement. But it would disappoint him so much. I don’t know if I have it in my heart to do that to him. He wants Ashra’s future to be secure. Jonash is a good match, politically, and in almost every other way. And then I remember that the night isn’t our own. “By the way, he’s joining us tonight.”

Elisha’s eyes just about pop out of her skull. “Jonash is?”

I roll my eyes, leaning back against the edge of the fountain and swinging my sandaled feet in the air. “After dinner he wants to meet us here. There’s some sort of party for the lieutenant’s birthday first. Unless, you know, rebellion calls them both away.” One can hope.

“Unlikely. Well, we better get in all the fun we can before our night turns political.” Elisha jumps to her feet. “Come on.”

Elisha is like the sun to me. She’s always shining, always optimistic. She has moments of sadness and hardship when she dims, like everyone else, but it doesn’t bother her that she’s fixed in one spot. She has no desire to leave Ashra, no curiosity about the monster-ridden earth below or the strange past before the Rending. I try to shed my worries now, to enjoy the fun of the Rending celebration.

Ulan is vibrant and bustling with out-of-town guests. Groups of Initiates walk through the crowd in their white robes, carrying sticks of chicken glazed with honey and tiny cakes of puffed flour and dusted sugar. Villagers dance in the square, wearing dresses of red and orange and yellow, the colors of the Phoenix and of our redemption. Elisha runs to the open window of one hut, where a man passes her the sticky-sweet skewers of honeyed chicken. We lick the hot, sweet meat as the honey dribbles onto our fingers. After, we buy two glasses of foamed pygmy goat milk blended with crushed red field berries, and then stuff our mouths with miniature puffed cakes and gluey spirals of bright orange melon paste. We eat and drink until the sugar overwhelms us and our foreheads pulse with headaches, and then Elisha grabs my sticky hands in hers and we dance in the square, spinning around and around as the sun begins to set, as the candles are lit in every window and along the edges of the wall.

Ulan is the only part of the floating continent to have a wall. It begins at the citadel and curves past the fountain and around the edge of the farmlands. It ends abruptly in the tangled forests, where the trees make their own wall of roots and thorns and brambles. At first, our ancestors never bothered to build a wall, since the edge of a floating continent isn’t something to be defended, nor is the village built directly on the brink. The schoolhouse is between the town and the farmlands, and children learn from an early age not to go wandering in the grassy fields that stretch toward the southern edge.

But when I was two, a terrible accident happened. One of the teachers in town was running late that morning. She’d raced to the henhouse to gather the eggs, and one of the chickens had gotten out into the farmlands. She’d just chased it down when she smelled her morning loaf burning in the oven. And so she rushed in to deal with that as well, and the whole time she’d left the door to her cottage open and her toddler son had wandered out into the long grasses to look for her. The villagers are still haunted by his screams, the helpless cries that pierced the morning quiet as he toppled suddenly off the edge of the continent.

His mother never got over the horrible tragedy. No one blamed her, of course, but she drowned in the guilt that my father said only a parent can suffer. Her heart heavy with grief, she jumped off the edge six months later, and so we built the wall to protect others from the same tragic fate.

The wall is mainly stones mortared together with a thick clay paste. I don’t know how well it would stand up to someone who wanted to topple it over, but it’s strong enough to hold against the strength of any child. I was only two at the time myself, so I can’t imagine the symbol of grief the wall is for the older citizens of Ulan. It is hauntingly beautiful with the Rending candles placed along the length of the edge, villagers bending to light them as the sky grows darker. The flames flicker against the stones, casting dancing shadows and light echoed by the fireflies gleaming in the forests to the north. They look like tufts of Phoenix down floating on the wind, carried any way they please, lighting the continent with their orange-and-yellow glow.

I feel claustrophobic suddenly, longing to go back to my outcrop and think about the hidden tome Aban concealed in the cupboard. I can’t face Jonash, or my father, or any of the politics ahead of me. It’s risky to climb the outcrop at night, although I’ve done it before to watch the rainbow of fireflies alighting on the wildflowers. Maybe I can go to the edge of Lake Agur and listen to the waters, close my eyes and pretend I’m sitting on the shore of the ocean.

I close my eyes now, imagining away the crowds of celebration. “Elisha,” I say, “let’s ditch the festival. Let’s go where that Burumu boor can’t find us.”

A deep voice answers, and it isn’t Elisha’s. “And where’s that?”

I open my eyes, and Jonash’s blue eyes study mine, the pale purple dusk shadowing the crinkle of his forced smile.

I’m horrified. The guilt sinks deep in the pit of my stomach, resting uneasily. Elisha stands to the side, her eyes wide and full of shared embarrassment.

“I’m so sorry,” I blurt out. “I didn’t mean anything against you.”

Jonash laughs a little. “I’m certain you didn’t,” he says, but I know he’s only being polite. I can see the confusion in his eyes, the expectation of an explanation. “Do I really come off as boorish?”

My cheeks blaze. “Of course not. I’m only feeling a little claustrophobic,” I try, waving my hand around at the crowds. By now the barley and malt have made their ways through the crowds, and the dancing has become much louder and far less coordinated. “It’s...it’s just been a long day.”

One of the dancers approaches, singing the verse of a ballad too loudly as he merrily shakes his glass at us. Jonash gently rests his hands on the man’s shoulders and turns him so he dances away, back toward the crowd. “I think I understand,” he says. “Shall we all three escape, then?”

Elisha’s eyes twinkle, and I know she thinks it’s Jonash being perfect again. And she’s right, of course. He’s being a gentleman about the whole mortifying situation. He offers his arm, and in front of the crowds, with my embarrassing words in mind, there’s nothing I can do but take it graciously. I link my arm around his and we walk toward the fountain, the blue light of the citadel’s crystal shining like a beacon in the growing dark. “I thought we could go to Lake Agur.”

“Too many mosquitos and flies at dusk,” Elisha says. “Why not the outcrop?”

Jonash raises an eyebrow. “The outcrop? Sounds intriguing.”

I want to shake Elisha. I will, later. The outcrop is my place, one I refuse to share with Jonash. “It’s nowhere important. But the outlands near the lake would be lovely.”

“Anywhere,” he says. “I’ve had enough politics for one night, as well.”

“The lieutenant’s birthday,” I answer, and the scene in the library floods back along with all my doubts.

The lights and songs of Ulan fade behind us as we start down the dirt path toward the citadel. Halfway along we turn down the northeastern path, past the landing pitch where the airship bobs like a puffy cloud in the dim light.

I slip my arm away from Jonash, pretending to smooth my hair back in the cold nighttime wind.

“The lieutenant seemed a bit off today,” I hazard. “Has anything happened?”

“Off?”

“The unrest in Burumu is perhaps on his mind?”

Jonash slows, his head tilted to the side as he thinks. “Not that I’m aware.”

“What is the unrest, exactly?”

He pauses for a moment as we walk in silence. “Just a little grumbling over ration allotment,” he says finally. “Nothing to trouble Your Highness.”

“Kali is fine,” I remind him. “And I’m glad to hear it. Because the strangest thing happened today, and I’m not sure what to make of it.”

“Oh?”

I’m hesitant to share with Jonash what’s happened, but maybe he’ll know more about it than me. “The lieutenant and Elder Aban were in the library. They were discussing a rebellion, and the annals.”

“The annals are rather dusty and educational for the lieutenant’s tastes.” Jonash laughs, and Elisha politely laughs with him.

But I don’t like that he’s avoided the word rebellion. My instinct says it isn’t the first he’s heard of it. “The lieutenant had a paper from the rebels,” I tell him, and the laughing stops.

I tell them the rest of the story, about the drawing of the Phoenix covering up part of the original illustration, about the red rings and the machine scribbled out by her tail. I tell them about the secret first volume Aban had under lock and key, and the discussion of an Initiate who may be causing trouble from Nartu. I tell them how the lieutenant wants to discredit the information as lies, which means there’s a dangerous truth embedded in it. Jonash’s face darkens, and then I know I was right to worry, that it hasn’t all been in my head.

“Have you spoken to the Monarch?” he says. His voice sounds off.

I shake my head. “He’s been so busy with the celebrations. I’m going to tell him as soon as I return tonight.”

“I would advise against it,” he tells me. “The Monarch has so much on his plate. I can assure you whatever the issue is, my father and the Elite Guard in Burumu can handle it.”

His advice annoys me. It’s like a patronizing pat on the head. “That’s the thing,” I say, before I can stop myself. “If this was a serious matter, you’d think the Sargon would’ve spoken up by now. Surely he doesn’t allow rebellion to take over Burumu?”

Jonash presses his lips together, likely to stop whatever words are dying to flow out. “Are you saying you have no confidence in my father, nor in me?” he says.

The question snaps me back into diplomacy. This is my fiancé, and I’m speaking without any tact at all. I don’t really care what he thinks of me, as I quietly seethe at him not taking me seriously. But I love my father, and I’m risking too much fanning flames between our families.

“Not at all,” I say, and I’m sure my face is flashing my irritation. “But something isn’t right about all this, and I won’t stop until I understand what it is. And that begins with informing my own father, who should know all rumors floating about the length of the sky.”

Jonash nods, but his eyes seem dim and distracted. “I see,” he says, but his tone disagrees. I assume he’s embarrassed, that whatever this rebellion is, it’s gone beyond the reach of his father, the Sargon, to deal with it. It’s a losing situation for him—if he doesn’t know of the rebellion, then he’s incompetent, and if he knows but can’t handle it, then he’s equally ill-equipped. Neither bodes well for an heir like him.

But the thought is mean-spirited. I didn’t know about the rebellion, either. Perhaps it’s new information that the lieutenant will share on their return. “I... I’m sure you will be able to address it when you return,” I offer.

“Indeed,” he says, and his eyes still look sunken in his face, but at least the anger has faded from his voice.

The path is dark now, the shining crystal of the citadel far behind us. Elisha reaches into her bag and pulls out a cast-iron lantern, carved all over with the shapes of stars and feathers for the light of the candle to dance through. We stop so she can strike the flint and light it, and she passes the lantern to me as well as the flint, which I slip into my pocket.

“Are we really going to go all the way to the outlands?” she says, and the candlelight flickers across her worried face. “I was only joking about the outcrop, you know. The sun’s set too quickly.” She looks around, and I know she fears the animals in the forests around us. We don’t have many predators on the continent, and they’re no bigger than deer—dwarf bears and wild boars mostly—but they’re protected by law in case we’re ever in desperate need to hunt for meat in years of drought or famine. There have been sightings of small dragons before, lighting up Lake Agur with fiery breaths, but they turned out to be a combination of lizards, fireflies and children’s wild imaginations. Monsters have never flown this high, but Elisha still fears the darkness. I’m sure our discussion of rebellion isn’t helping.

“We can turn back if you want,” I say. “And go tomorrow, in the light.”

“I was hoping to see the fireflies,” Jonash says, crestfallen. “I’ve heard they flash in every color in Ashra.”

“You two go ahead, then,” Elisha says, and I shoot her a warning look in the lantern light. You’re going to send me alone with him?

She arches her eyebrows in protest. He’s the son of the Sargon, she’s thinking. He’s a gentleman. But neither of us knows him, not really. I doubt he’d hurt me or force anything on me, for that would certainly break off the engagement and cause a terrible feud between our families and our continents. No, I’m much more afraid he’ll try to win me over, or that he’ll lean in for a kiss and I’ll lean away and everything will become terribly awkward.

“Let’s all go on, then,” Elisha says after a moment. “But only for a quick look, and we’ll head straight back.”

“Agreed,” I say. “It’s only about ten minutes to the clearing anyway.”

We walk the rest of the forest path in silence, listening to the wind rustling the leaves. I wish I’d brought my cloak. The nighttime air is always freezing in the sky.

The trees pull away then, and the outlands are before us. The tall grasses bend in the wind, rustling with the sound of the cold breeze. Fireflies thread through them like garlands of candlelight, flashing green and yellow and orange. I hold the lantern behind us to let our eyes adjust, and then the pink and purple and blue fireflies lift up, hovering above the grasses in wreaths of color.

Jonash steps forward, watching their colors flash. They go dim in front of him, blacking out along his entire path in their fear. But a moment later they light behind him, surrounding him in distant light.

“Go on,” Elisha whispers, nudging me forward. I wish she’d stop pushing me. But seeing Jonash in the field surrounded by those lights, seeing him appreciate the beauty of Ashra, makes me realize there’s so much about him I don’t know yet. Maybe this is an opportunity. He listened to my concerns about the strange extra tome that Aban and the lieutenant whispered over, even if he was a little patronizing. He didn’t take offense to what I said in the village. Elisha’s right that I do owe him more of a chance.

The grass scrapes against the sides of my ankles and the gaps between my sandal straps. The edges of the blades are sticky with sap and dry from too much sun. Dimmed fireflies accidentally bump into my arms and legs as I walk, and the lantern swings patterns of stars and feathers around the grasses. The fireflies darken in swarms around me, like snuffed-out candles.

“It’s wonderful,” Jonash says as I reach his side. “We only have yellow and orange fireflies in Burumu.”

“Most villagers in Ulan don’t come out as far as the outlands,” I say. “The edge of the continent is uneven here and difficult to see in the fields.” He looks alarmed, so I raise my hands to reassure him, the lantern swinging back and forth. “It’s out that way,” I say. “You can see it easily if you look for the moons hitting the rock.”

He peers over, so I take him closer to the edge to look. To me it’s like a lighting strip, silver and shiny as it loops along the side of the clearing. The two moons in the sky, one a crescent and one waxing full, beam down on the sparkling crystal fragments embedded in the stone of the continent’s edge. It’s like a glittering warning sign curving along the outlands. “See? Easy to spot once you know what to look for,” I tell him.

He crouches down to look at the sparkling stone. “I see it. It’s like a thread of glistening silver.”

I turn away, swinging the lantern at my side. The fireflies scatter from its light. “We should go back soon. Elisha will get spooked if we wait too long.”

“Of course,” he says, straightening up. “Only a little longer, and then I’ll escort you both, I promise.”

I roll my eyes, glad he can’t see my face. I don’t need his escort. I know every stone of Ashra, every curve of rock and packed earth. Nothing can harm me here. Only the wild animals need be avoided.

He follows a flashing blue firefly then, dangerously close to the edge. I wonder why he continues to veer so close now that he knows how to look for the silvery lip of the continent. Perhaps he’s fearless like me. Or perhaps he’s just foolish.

Now it’s as if he’s walking along a thin rope. My heart is fluttering. It wouldn’t do for my fiancé to drop off the side of the world. The Sargon wouldn’t be pleased, and neither would my father. “You’re too close, Jonash.”

He doesn’t answer, but stretches his arms out to the side to help balance. The fireflies shy away in clouds of twinkling light.

I take a step forward. “Jonash,” I try again. “Come away from the edge. The sheer crystal is slippery.” I take another step. “I’m sure it’s different on Burumu, but here...”

I don’t have a chance to finish my sentence. He begins toppling from side to side, and the horror claws at my insides. Before I realize it I’m leaping forward, throwing my arms around his waist to pull him into the tall grasses. He whirls around from the impact, the weight of him unbalancing my own footing.

I feel the scrape of the sharp crystals as they dig into my ankle, as my foot slips over the edge of the continent.

There’s no time to scream or think. My balance is off, and I’m falling backward, away from Jonash’s grim face. The lantern jangles against the cliff as it drops from my hand and tumbles sideways over the edge. Jonash’s hands on are my wrists, pulling them from his sides before we both go over. He falls stomach-down onto the grasses as my other foot slips over the side, shards of rock and dirt scraping the insides of my arms as I cling to the continent.

The cold wind gusts against me as I hang on. My feet swing and flail, but there’s nothing but air around them. The world is dark except for the glowing fireflies and the silver strip of crystal rock.

My wrists are slipping from Jonash’s fingers. I can barely breathe. “I can’t...”

“Kali, hang on,” he says. “Elisha! Help!” His shouts send the fireflies whirling in clouds.

I can hear Elisha yelling something, but my pulse is racing in my ears and I can’t make out a thing.

Jonash’s hands slide up my wrists, and he curls my fingers into the grasses and the thin layer of earth that clings to the bedrock. I grasp at them, but the grasses come up in handfuls. Is he that much of an idiot to think they’ll help keep me from falling? “Pull me up!” I scream at him.

The coolness of his fingers is gone, and the grass slips away. The edge of crystal rock scrapes the skin from the palms of my hands as I fall off the edge of the world.

I can hear screams, but I can’t tell if they’re mine. My body tumbles through the air, spinning over and over until I don’t know anything but cold gusts of black wind. The moons blink their stark white faces in a blur of light that tumbles over itself until I’m completely dizzy. The rainbow lights of the fireflies stretch away like stars until I see nothing but blackness.

I’m going to die. I’m going to hit the earth and the impact will kill me.

I can’t see in the darkness as I tumble round and round. I don’t know when I’ll hit, but it’s coming. I can’t tell if I’ve been falling for minutes or hours. The skirts of my dress are tangled around my legs. The wind whistles in my ears until I can’t hear or feel anything else.

I start to slow then, and the world stops tumbling. Have I died? They say when you die, the Phoenix burns a hole in the world and clasps you gently in her talons to take you away. But there’s no fire here, only cold air and a strange humming noise. And then a pale light spreads around me.

I look at my hand, drenched in a faint kaleidoscope of colors. It’s almost invisible, like when I catch a glimpse of rainbow light dancing on my hand from the ripples of Lake Agur. I’ve slowed so much it’s like floating in honey, the air thick and sluggish around me. I’m still falling, but drifting like a feather, buoyed gently down like I’m sinking into the lake.

And then there’s a strange sucking sound, and the rainbow lights waft from my fingers. I’m falling at full speed again, my back to the earth and my eyes cast upward. I look up at the two moons as they beam, unyieldingly bright in the sea of darkness.

I hear a great crash as if I’m in another world, and I feel a sharp pain everywhere at once. Then there is nothing but blackness and void.