Читать книгу The Glass Palace - Amitav Ghosh - Страница 17

Nine

ОглавлениеIn 1905, the nineteenth year of the King’s exile, a new District Collector arrived in Ratnagiri. The Collector was the district’s administrative head, the official who was ultimately responsible for dealing with the Burmese Royal Family. The job was an important one and the officials who were appointed to this post were almost always members of the Indian Civil Service – the august cadre of officials who administered Britain’s Indian possessions. To join the Indian Civil Service candidates had to pass a difficult examination that was held in England. The overwhelming majority of those who qualified were British, but there were also among them a small number of Indians.

The Collector who arrived in 1905 was an Indian, a man by the name of Beni Prasad Dey. He was in his early forties, and an outsider to the Ratnagiri region: he was a Bengali from Calcutta, which lay diagonally across the map of India, at the other end of the country. Collector Dey was slim and aquiline, with a nose that ended in a sharp, beak-like point. He dressed in finely-cut Savile Row suits and wore gold-rimmed eyeglasses. He arrived in Ratnagiri accompanied by his wife, Uma, who was some fifteen years his junior, a tall, vigorous-looking woman, with thick, curly hair.

King Thebaw was watching from his balcony when Ratnagiri’s officialdom gathered at the Mandvi jetty to receive the new Collector and his young wife. The first thing he noticed about them was that the new Madame Collector was dressed in an unusual garment. Puzzled, he handed his binoculars to the Queen. ‘What’s that she’s wearing?’

The Queen took a long look. ‘It’s just a sari,’ she said at last. ‘But she’s wearing it in the new style.’ She explained that an Indian official had made up a new way of wearing a sari, with odds and ends borrowed from European costume – a petticoat, a blouse. She’d heard that women all over India were adopting the new style. But of course everything came late to Ratnagiri – she herself had never had an opportunity to look into this new fashion at first hand.

The Queen had seen many Collectors come and go, Indian and English; she thought of them as her enemies and gaolers, upstarts to be held in scant regard. But in this instance she was intrigued. ‘I hope he’ll bring his wife when he comes to call. It’ll be interesting to see how this kind of sari is worn.’

Despite this propitious beginning the Royal Family’s first meeting with the new Collector came close to ending in disaster. Collector Dey and his wife had arrived at a time when politics was much on people’s minds. Every day there were reports of meetings, marches and petitions: people were being told to boycott British-made goods; women were making bonfires of Lancashire cloth. In the Far East there was the war between Russia and Japan and for the first time it looked as though an Asian country might prevail against a European power. The Indian papers were full of news of this war and what it would mean for colonized countries.

It was generally not the King’s custom to meet with officials who came to Outram House. But he had been following the Russo-Japanese war very closely and was keen to know what people thought of it. When the new Collector and his wife came to call, the King’s first words were about the war. ‘Collector-sahib,’ he said abruptly, ‘have you seen the news? The Japanese have defeated the Russians in Siberia?’

The Collector bowed stiffly, from the waist. ‘I have indeed seen reports, Your Highness,’ he said. ‘But I must confess that I do not believe this to be an event of any great significance.’

‘Oh?’ said the King. ‘Well, I’m surprised to hear that.’ He frowned, in a way that made it clear that he wasn’t about to let the subject drop.

The night before Uma and the Collector had been briefed at length on their forthcoming visit to Outram House. They’d been told that the King was never present at these occasions: it was the Queen who would receive them, in the reception room on the ground floor. But they’d entered to find the King very much present: he was dressed in a crumpled longyi and was pacing the floor, smacking his thigh with a rolled-up newspaper. His face was pale and puffy, and his wispy grey hair was straggling unkempt down the back of his neck.

The Queen, on the other hand, was exactly where she was meant to be: sitting rigidly upright on a tall chair, with her back to the door. This, Uma knew, was a part of the set order of battle: visitors were expected to walk in and seat themselves on low chairs around Her Highness, with no words of greeting being uttered on either side. This was the Queen’s way of preserving the spirit of Mandalay protocol: since the representatives of the British were adamant in their refusal to perform the shiko, she in turn made a point of not acknowledging their entry into her presence.

Uma had been told to be on her guard in the reception room, to look out for delinquent sacks of rice and stray bags of dal. This room was sometimes used as an auxiliary storeroom and several unwary visitors were known to have come to grief in its hidden pitfalls: it was not unusual to find heaps of chillies hidden under its sofas and jars of pickles stacked on its bookshelves. On one occasion a beefy superintendent of police had sat down heavily on the spiny remains of a dried fish. Another time, ambushed by a powerful whiff of pepper, a venerable old district judge had sneezed his false teeth clear across the room. They had fallen clattering at the Queen’s feet.

These reception-room stories had caused Uma much apprehension, prompting her to secure her sari with an extravagant number of clips and safety-pins. But on entering the room she’d found its effects to be not at all as expected. Far from being put out, she felt oddly comforted by the familiar fragrances of rice and mung dal. In any other setting Queen Supayalat, with her mask-like face and mauve lips, would have seemed a spectral and terrifying figure. But the odours of domesticity seemed to soften her edges a little, adding an element of succour to her unyielding presence.

Across the room, the King was smacking his newspaper loudly on his palm. ‘Well, Collector-sahib,’ he said, ‘did you ever think that we would live to witness the day when an Eastern country would defeat a European power?’

Uma held her breath. Over the last few weeks the Collector had conducted many heated arguments on the implications of a Japanese victory over Russia. Some had ended in angry outbursts. She watched anxiously now as her husband cleared his throat.

‘I am aware, Your Highness,’ the Collector said evenly, ‘that Japan’s victory has resulted in widespread rejoicing among nationalists in India and no doubt in Burma too. But the Tsar’s defeat comes as no surprise to anyone, and it holds no comfort for enemies of the British Empire. The Empire is today stronger than it has ever been. You have only to glance at a map of the world to see the truth of this.’

‘But in time, Collector-sahib, everything changes. Nothing goes on for ever.’

The Collector’s voice grew sharper. ‘May I remind Your Highness that while Alexander the Great spent no more than a few months in the steppes of central Asia, the satrapies he founded persisted for centuries afterward? Britain’s Empire is, by contrast, already more than a century old, and you may be certain, Your Highness, that its influence will persist for centuries more to come. The Empire’s power is such as to be proof against all challenges and will remain so into the foreseeable future. I might take the liberty of pointing out, Your Highness, that you would not be here today if this had been pointed out to you twenty years before.’

The King flushed, staring speechlessly at the Collector. It fell to the Queen to answer for him. She leant forward, digging her long, sharp fingernails into the arms of her chair. ‘That is enough, Mr Collector,’ she said. ‘Enough, has karo.’ There was a moment of stillness in which the only sound was that of the Queen’s nails, raking the polished arms of her chair. The room seemed to shimmer as though the floor had given off a sudden haze of heat.

Uma was seated between Dolly and the Second Princess. She had listened to her husband’s exchange with the King in dismayed silence, sitting frozen in her place. On the wall ahead of her was a small watercolour. The painting was a depiction of a landscape at sunrise, a stark red plain dotted with thousands of mist-wreathed pagodas. Suddenly, with a clap of her hands, Uma uttered a loud cry. ‘Pagan!’

The word had the effect of an explosion in a confined space. Everyone jumped, turning to look in Uma’s direction. She raised a hand to point. ‘On the wall – it’s a picture of Pagan, isn’t it?’

The Second Princess was sitting next to Uma. She seized eagerly on this diversion. ‘Yes – that is it. Dolly can tell you – she painted it.’

Uma turned to the slim upright woman on her left. Her name was Dolly Sein, she recalled: they had been introduced on the way in. Uma had noticed that there was something unusual about her, but she’d been too busy concentrating on protocol to give the matter any further thought.

‘Did you really paint that?’ Uma said. ‘Why, it’s wonderful.’

‘Thank you,’ Dolly said quietly. ‘I copied it from a book of prints.’ Their glances crossed and they exchanged a quick smile. Suddenly Uma knew what it was that she’d been struck by: this Miss Sein was perhaps the loveliest woman she’d ever set eyes on.

‘Madame Collector,’ the Queen tapped a knuckle on the arm of her chair, ‘how did you know that was a picture of Pagan? Have you had occasion to visit Burma?’

‘No,’ Uma said regretfully. ‘I wish I had but I haven’t. I have an uncle in Rangoon and he once sent me a picture.’

‘Oh?’ The Queen nodded; she was impressed by the way the young woman had intervened to save the situation. Self-possession was a quality she’d always admired. There was something attractive about this woman, Uma Dey; the liveliness of her manner was a welcome contrast to her husband’s arrogance. If not for her presence of mind she would have had to order the Collector out of the house and that could only have ended badly. No, this Mrs Dey had done well to speak when she did.

‘We would like to ask you, Madame Collector,’ the Queen said, ‘what is your real name? We have never been able to accustom ourselves to your way of naming women after their fathers and husbands. We do not do this in Burma. Perhaps you would not object to telling us your own given name?’

‘Uma Debi – but everyone calls me Uma.’

‘Uma?’ said the Queen. ‘That is a name that is familiar to us. I must say, you speak Hindustani well, Uma.’ There was a note of unfeigned appreciation in her voice. Both she and the King spoke Hindustani fluently and this was the language she preferred to use in her dealings with officials. She had found that her use of Hindustani usually put the Government’s representatives at a disadvantage – especially the Indians. British civil servants often spoke Hindustani well and those who didn’t had no qualms about answering in English. The Indians, on the other hand, were frequently Parsis or Bengalis, Mr Chatterjee this or Mr Dorabjee that, and they were rarely fluent in Hindustani. And unlike their British counterparts they were hesitant about switching languages; it seemed to embarrass them that the Queen of Burma could speak Hindustani better than they. They would stumble and stutter and within minutes she would have their tongues tied in knots.

‘I learnt Hindustani as a child, Your Highness,’ Uma said. ‘We lived in Delhi for a while.’

‘Achha? Well, now we would like to ask something else of you, Uma.’ The Queen made a beckoning gesture. ‘You may approach us.’

Uma went over to the Queen and lowered her head.

‘Uma,’ the Queen whispered, ‘we would like to examine your garments.’

‘Your Highness!’

‘As you can see, my daughters wear their saris in the local style. But I prefer this new fashion. It is more elegant – the sari looks more like a htamein. Would it be too great an imposition to ask you to reveal the secrets of this new style to us?’

Uma was startled into laughter. ‘I would be glad to, whenever you please.’

The Queen turned stiffly to the Collector. ‘You, Collector-sahib, are no doubt impatient to be on your way to the Cutchery and the many pressing tasks that await you. But may I ask if you will permit your wife to remain with us a little longer?’

The Collector left, and in defiance of the initial auguries of disaster, the visit ended very amicably, with Uma spending the rest of the afternoon in Outram House, chatting with Dolly and the Princesses.

The Collector’s house was known as the Residency. It was a large bungalow with a colonnaded portico and a steep, red-tiled roof. It stood on the crest of a hill, looking southward over the bay and the valley of the Kajali river. It was surrounded by a walled garden that stretched a long way down the slope, stopping just short of the river’s gorge.

One morning Uma discovered a narrow entrance hidden behind a thicket of bamboo at the bottom of her garden. The gate was overgrown with weeds but she was able to open it just wide enough to squeeze through. Twenty feet beyond, a wooded outcrop jutted out over the valley of the Kajali river. There was a peepul at the lip of the gorge, a majestic old tree with a thick beard of aerial roots hanging from its gnarled grey branches. She could tell that goats came to graze there: the earth beneath the tree’s canopy had been cropped clean of undergrowth. She could see trails of black droppings leading down the slope. The goatherds had built themselves a platform to sit on by heaping earth and stones around the peepul’s trunk.

Uma was amazed by the view: the meandering river, the estuary, the curve of the bay, the windswept cliffs – she could see more of the valley from here than from the Residency on top of the hill. She returned the next day and the day after. The goatherds came only at dawn and for the rest of the day the place was deserted. She took to slipping out of the house every morning, leaving the door of her bedroom shut, so that the servants would think she was still inside. She would sit in the peepul’s deep shade for an hour or two with a book.

One morning Dolly surprised her by appearing unexpectedly out of the peepul’s beard of hanging roots. She’d called to return some clothes that Uma had sent over to Outram House – petticoats and blouses, for the Princesses to have copied by their tailors. She’d waited in the drawing room of the Residency while the servants went looking for Uma. They’d looked everywhere before giving up: memsahib wasn’t at home, they said, she must have slipped out for a walk.

‘How did you know I was here?’

‘Our coachman is related to yours.’

‘Did Kanhoji tell you?’ Kanhoji was the elderly coachman who drove Uma around town.

‘Yes.’

‘I wonder how he knew about my secret tree.’

‘He said he’d heard about it from the herdsmen who bring their goats here in the morning. They’re from his village.’

‘Really?’ Uma fell silent. It was odd to think that the goatherds were just as aware of her presence as she was of theirs. ‘Well, the view’s wonderful, don’t you think?’

Dolly gave the valley a perfunctory glance. ‘I’ve grown so used to it I never give it a thought any more.’

‘I think it’s amazing. I come here almost every day.’

‘Every day?’

‘Just for a bit.’

‘I can see why you would.’ She paused to look at Uma. ‘It must be lonely for you here, in Ratnagiri.’

‘Lonely?’ Uma was taken aback. It hadn’t occurred to her to use that word of herself. It was not as though she never met anyone, or that she was ever at a loss for things to do – the Collector made sure of that. Every Monday his office sent up a memorandum listing her engagements for the week – a municipal function, a sports day at a school, a prize-giving at the vocational college. She usually had only one appointment a day, not so many as to keep her uncomfortably busy nor so few as to make her days seem oppressively long. She went through the list carefully when it arrived at the beginning of the week, and then she put it on her dressing table, with a weight on it, so it wouldn’t blow away. The thought of missing an appointment worried her, although there was little chance of that. The Collector’s office was very good about sending reminders: a peon came up to the Residency about an hour before each new appointment to tell Kanhoji to bring the gaari round. She’d hear the horses standing under the porch; they’d snort and kick the gravel, and Kanhoji would click his tongue, tuk-tuk-tuk.

The nicest part of these appointments was the journey into town and back. There was a window between the coach and the driver’s bench. Every few minutes Kanhoji would stick his tiny, wrinkled face into the window and tell her about the places around them – the Cutchery, the gaol, the college, the bazaars. There were times when she was tempted to get off so she could go into the bazaars and bargain with the fishwives. But she knew there would be a scandal; the Collector would come home and say: ‘You should just have let me know so that I could have arranged some bandobast.’ But the bandobast would have destroyed any pleasure she might have taken in the occasion: half the town would have gathered, with everyone falling over themselves to please the Collector. The shopkeepers would have handed over anything she so much as glanced at, and when she got home the bearers and the khansama would have sulked as though she’d dealt them a reproach.

‘What about you, Dolly?’ Uma said. ‘Are you lonely here?’

‘Me? I’ve lived here nearly twenty years, and this is home to me now.’

‘Really?’ It struck Uma that there was something almost incredible about the thought that a woman of such beauty and poise had spent most of her life in this small provincial district town.

‘Do you remember anything of Burma?’

‘I remember the Mandalay palace. Especially the walls.’

‘Why the walls?’

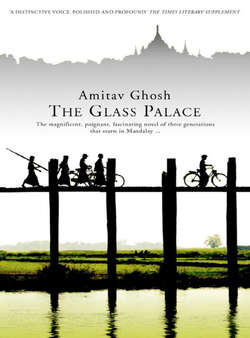

‘Many of them were lined with mirrors. There was a great hall called the Glass Palace. Everything there was of crystal and gold. You could see yourself everywhere if you lay on the floor.’

‘And Rangoon? Do you remember Rangoon?’

‘Our steamer anchored there for a couple of nights, but we weren’t allowed into the city.’

‘I have an uncle in Rangoon. He works for a bank. If I’d visited him I’d be able to tell you about it.’

Dolly turned her eyes on Uma’s face. ‘Do you think I want to know about Burma?’

‘Don’t you?’

‘No. Not at all.’

‘But you’ve been away so long.’

Dolly laughed. ‘I think you’re feeling a little sorry for me. Aren’t you?’

‘No,’ Uma faltered. ‘No.’

‘There’s no point in being sorry for me. I’m used to living in places with high walls. Mandalay wasn’t much different. I don’t really expect much else.’

‘Do you ever think of going back?’

‘Never.’ Dolly’s voice was emphatic. ‘If I went to Burma now I would be a foreigner – they would call me a kalaa like they do Indians – a trespasser, an outsider from across the sea. I’d find that very hard, I think. I’d never be able to rid myself of the idea that I would have to leave again one day, just as I had to before. You would understand if you knew what it was like when we left.’

‘Was it very terrible?’

‘I don’t remember much, which is a kind of mercy, I suppose. I see it in patches sometimes. It’s like a scribble on a wall – no matter how many times you paint over it, a bit of it always comes through, but not enough to put together the whole.’

‘What do you see?’

‘Dust, torchlight, soldiers, crowds of people whose faces are invisible in the darkness …’ Dolly shivered. ‘I try not to think about it too much.’

After this, in what seemed like an impossibly short time, Dolly and Uma became close friends. At least once a week, and sometimes twice and even more, Dolly would come over to the Residency and they would spend the day together. Usually they stayed in, talking and reading, but from time to time Dolly would have an idea for an expedition. Kanhoji would drive them down to the sea or into the countryside. When the Collector was away touring the district, Dolly would stay over to keep Uma company. The Residency had several guest rooms and Uma assigned one of these exclusively to Dolly. They would sit up talking late into the night. Often they would wake up curled on one another’s beds, having drifted off to sleep in mid-conversation.

One night, plucking up her courage, Uma remarked: ‘One hears some awful things about Queen Supayalat.’

‘What?’

‘That she had a lot of people killed … in Mandalay.’

Dolly made no answer but Uma persisted. ‘Doesn’t it frighten you,’ she said, ‘to be living in the same house as someone like that?’

Dolly was quiet for a moment and Uma began to worry that she’d offended her. Then Dolly spoke up. ‘You know, Uma,’ she said in her softest voice. ‘Every time I come to your house, I notice that picture you have, hanging by your front door …’

‘Of Queen Victoria, you mean?’

‘Yes.’

Uma was puzzled. ‘What about it?’

‘Don’t you sometimes wonder how many people have been killed in Queen Victoria’s name? It must be millions, wouldn’t you say? I think I’d be frightened to live with one of those pictures.’

A few days later Uma took the picture down and sent it to the Cutchery, to be hung in the Collector’s office.

Uma was twenty-six and had already been married five years. Dolly was a few years older. Uma began to worry: what was Dolly’s future to be? Was she never to marry or have children? And what of the Princesses? The First Princess was twenty-three, the youngest eighteen. Were these girls to have nothing to look forward to but lifetimes of imprisonment?

‘Why doesn’t someone do something,’ Uma said to the Collector, ‘about arranging marriages for the girls?’

‘It’s not that no one’s tried,’ the Collector replied. ‘It’s the Queen who won’t allow it.’

In his offices at the Cutchery, the Collector had found a thick file of correspondence chronicling his predecessors’ attempts to deal with the question of the Princesses’ futures. The girls were in the prime of their womanhood. If there were to be a scandal or an accident at Outram House the incumbent Collector would be held responsible: the Bombay secretariat had left no room for doubt on this score. In order to protect themselves, several previous Collectors had tried to find suitable grooms for the Princesses. One had even written to his colleagues in Rangoon, to make enquiries about eligible Burmese bachelors – only to learn that there were only sixteen such men in the whole country.

The custom of the ruling dynasties of Burma was to marry very closely within their houses. Only a man descended of Konbaung blood in both lines was eligible to marry into the Royal Family. It was the Queen who was to blame for the fact that there were now very few such pure-blooded princes left: it was she who had decimated her dynasty by massacring all of Thebaw’s potential rivals. As for the few eligible men that there were, none found favour with the Queen. She announced that not a single one of them was a fit match for a true-born Konbaung Princess. She would not allow her daughters to defile their blood by marrying beneath themselves.

‘But what about Dolly?’ Uma said to the Collector. ‘Dolly doesn’t have to worry about finding a prince.’

‘That’s true,’ said the Collector, ‘but hers is an even stranger circumstance. She’s spent her whole life in the company of the four Princesses. But she’s also a dependant, a servant, of unknown family and origin. How would you set about finding a husband for her? Where would you start: here or in Burma?’

Uma had no answer for this. Neither she nor Dolly had ever broached the subject of marriage or children. With some of her other friends, Uma could talk of little else but of husbands, marriage, children – and of course, of remedies for her own childlessness. But with Dolly it was different: theirs was not the kind of friendship that was based on intimate disclosure and domesticity – quite the opposite. Both she and Dolly knew instinctively what could not be spoken of – Uma’s efforts to conceive, Dolly’s spinsterhood – and it was this that lent their meetings such an urgent wakefulness. When she was with Dolly, Uma felt as though a great burden had dropped from her mind, that she could look outside herself, instead of worrying about her own failings as a wife. Driving in the countryside for instance, she would marvel at the way in which people came running out of their houses to talk to Dolly, to hand her little odds and ends, fruits, a few vegetables, lengths of cloth. They would talk for a while, in Konkani, and when they were on their way again, Dolly would smile and say, in explanation, ‘That woman’s uncle [or brother or aunt] used to work at Outram House.’ Despite her shrugs of self-deprecation, Uma could tell that there was a depth to these connections that went far beyond the casual. Often Uma longed to know who exactly these people were and what they and Dolly were speaking of. But in these encounters it was she who was the outsider, the memsahib: to her, for once, fell the silence of exile.

Occasionally, when the crowds around them grew too large, Kanhoji would issue scoldings from his bench, telling the villagers to clear the way for the Collector’s gaari, threatening to call the police. The women and children would glance at Uma; on recognizing the Collector’s wife, their eyes would widen and they would shrink away.

‘You see,’ Dolly said once, laughing. ‘The people of your country are more at home with prisoners than gaolers.’

‘I’m not your gaoler.’

‘What are you then?’ Dolly said, smiling, but with a note of challenge audible in her voice.

‘A friend. Surely?’

‘That too, but by accident.’

Despite herself, Uma was glad of the note of scorn in Dolly’s voice. It was a tonic restorative to the envy and obsequiousness she met with everywhere else, as the wife of the Collector and the district’s pre-eminent memsahib.

One day, while driving out in the coach, Dolly had a sharp exchange of words with Kanhoji through the connecting window. They quickly became absorbed in their argument and Dolly seemed almost to forget Uma’s presence. At intervals she made attempts to resume her normal manner, pointing at landmarks, and offering anecdotes about villages. But each time her anger got the better of her so that within moments she was at it again, whipping round to hurl a few more words at the coachman.

Uma was mystified: they were speaking in Konkani and she could understand nothing of what they said. What could they possibly be arguing about with their voices tuned to the intimately violent pitch of a family quarrel?

‘Dolly, Dolly,’ Uma shook her knee, ‘what on earth is the matter?’

‘Nothing,’ Dolly said, pressing her lips primly together. ‘Nothing at all. Everything is all right.’

They were on their way to the Bhagavati temple, which stood on the windswept cliffs above the bay, sheltered by the walls of Ratnagiri’s medieval fort. As soon as the gaari came to a halt Uma took hold of Dolly’s arm and led her towards the ruined ramparts. They climbed up to the crenellations and looked over: beneath them, the wall fell away in a straight line, dropping sheer into the sea a hundred feet below.

‘Dolly, I want to know what the matter is.’

Dolly shook her head distractedly. ‘I wish I could tell you but I can’t.’

‘Dolly, you can’t shout at my coachman and then refuse to tell me what you were talking about.’

Dolly hesitated and Uma urged her again: ‘You have to tell me, Dolly.’

Dolly bit her lip, looking intently into Uma’s eyes. ‘If I tell you,’ she said, ‘will you promise not to tell the Collector?’

‘Yes. Of course.’

‘You promise?’

‘Solemnly. I promise.’

‘It’s about the First Princess.’

‘Yes? Go on.’

‘She’s pregnant.’

Uma gasped, her hand flying to her mouth in disbelief. ‘And the father?’

‘Mohan Sawant.’

‘Your coachman?’

‘Yes. That’s why your Kanhoji is so angry. He is Mohanbhai’s uncle. Their family want the Queen to agree to a marriage so that the child will not be born a bastard.’

‘But, Dolly, how could the Queen allow her daughter to marry a coachman?’

‘We don’t think of him as a coachman,’ Dolly said sharply. ‘He’s Mohanbhai to us.’

‘But what about his family, his background?’

Dolly flicked her wrist in a gesture of disgust. ‘Oh, you Indians,’ she said. ‘You’re all the same, all obsessed with your castes and your arranged marriages. In Burma when a woman likes a man, she is free to do what she wants.’

‘But, Dolly,’ Uma protested, ‘I’ve heard that the Queen is very particular about these things. She thinks there’s not a man in Burma who’s good enough for her daughters.’

‘So you’ve heard about the list of husbands-to-be?’ Dolly began to laugh. ‘But you know, those men were just names. The Princesses knew nothing about them. To marry one of them would have been a complicated thing, a matter of state. But what’s happened between Mohanbhai and the Princess is not a complicated thing at all. It’s very simple: they’re just a man and a woman who’ve spent years together, living behind the same walls.’

‘But the Queen? Isn’t she angry? The King?’

‘No. You see, all of us are very attached to Mohanbhai – Min and Mebya most of all. In our different ways I think we all love him a little. He’s been with us through everything, he’s the one person who’s always stood beside us. In a way it’s he who’s kept us alive, kept us sane. The only person who’s really upset by this is Mohanbhai. He thinks your husband will send him to gaol when he finds out.’

‘What about the Princess? How does she feel?’

‘It’s as though she’s been reborn – rescued from a house of death.’

‘And what of you, Dolly? We never talk of you or your future. What about your prospects of marriage, of having children of your own? Do you never think of these things?’

Dolly leant over the wall, fixing her eyes on the pounding sea. ‘To tell you the truth, Uma, I used to think of children all the time. But once we learnt about the Princess’s child – Mohanbhai’s child – a strange thing happened. Those thoughts vanished from my mind. Now when I wake up I feel that the child is mine, growing inside me. This morning, I heard the girls asking the First Princess: “Has the child grown?” “Did you feel her move last night?” “Where are her heels this morning?” “Can we touch her head with our hands?” I was the only one who didn’t need to ask her anything: I felt that I could answer every one of those questions myself; it was as though it were my own child.’

‘But, Dolly,’ Uma said gently, ‘this is not your child. No matter how much it may seem your own, it is not, and never will be.’

‘It must seem very strange to you, Uma. I can understand that it would, to someone like you. But it’s different for us. At Outram House we lead very small lives. Every day for the last twenty years we have woken to the same sounds, the same voices, the same sights, the same faces. We have had to be content with what we have, to look for what happiness we can find. For me it does not matter who is bearing this child. In my heart I feel that I am responsible for its conception. It is enough that it is coming into our lives. I will make it mine.’

Glancing at Dolly, Uma saw that her eyes were brimming with tears. ‘Dolly,’ she said, ‘don’t you see that nothing will be the same after the birth of this child? The life you’ve known at Outram House will end. Dolly, you’ve got to leave while you can. You are free to go: you alone are here of your own will.’

‘And where would I go?’ Dolly smiled at her. ‘This is the only place I know. This is home.’