Читать книгу Unicorn - Amrou Al-Kadhi - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеFor the twenty-fourth night that August, I found myself crossed-legged on the floor of a damp, pungent dressing room. As the rumblings of an Edinburgh crowd reverberated from the venue next door – I say venue, it was more like a cave – I used my little finger to apply gold pigment to my emerald-painted lips. Denim, the drag troupe that I set up seven years earlier, had survived the gruelling Fringe Festival, and we were one show away from crossing our scratched heels over the finish line.

A month of performances, often two a day, had taken its toll. My skin was at war with the industrial quantity of make-up it was being suffocated in (a two-hour procedure each time); I had obliterated my left kneecap because of a wannabe-rockstar ‘jump-and-slam-onto-the-ground’ move I felt impelled to perform each show; and a boy I was seeing had suddenly disappeared on me (I secretly hoped that death, instead of rejection, would be the explanation, but it turned out he was a ghost of a different sort: he had indeed stopped fancying me).

Despite feeling so weathered, I was itching to get onstage again. I always feel empowered when I’m in drag and entertaining a crowd – it’s my sanctuary, a space where I invite the audience into my own reality, where I don’t need to adhere to the rules of anybody else’s. No matter how low I’m feeling, the transformative power of make-up and costume is galvanising; for most of my life I’ve felt like a failure by male standards, and drag allows me to convert my exterior into an image of defiant femininity. This particular show was always exhilarating to perform, because it was the first time I honestly articulated my tumultuous relationship with Islam onstage, trying to mine humour in the unexpected parallels between being queer and being Muslim. How I haven’t been hit with a fatwa yet, I do not know.

A student volunteer usher told us we were moments away from the start of the show, and I did my pre-show ritual where I box with the air and shout ‘IT’S GLAMROU, MOTHERFUCKERS’. It comforts me to imagine my haters as the punch bag ‘motherfuckers’. Then I formed a circle with my other queens, our hands all joined at the centre in a moment of communion. The synth chords burst through the speakers, and the audience whooped as we strutted through a blackout onto the stage, our backs facing the crowd, pretending that the actual sight of our faces would be some sort of reward. A suspended beat, then lights pummelled the stage. I thrust my arms above me as if it were Wembley (I won’t lie; it usually is in my mind), and eyed the dripping condensation coating the cave ceiling, one drop a moment away from plopping on my face. After a prolonged and hyperbolic musical introduction – allow a queen her fifteen minutes – the show began with each of us turning to face the crowd one by one, until I pivoted around last. The next part was supposed to be me proclaiming ‘I AM ISLAM’, followed by the Muslim call to prayer remixed with Lady Gaga’s ‘Bad Romance’.

But on this final night, as I opened my mouth to start the show, I felt a little bit of sick at the back of my throat, and I found I couldn’t make a sound. Six Muslim women, the majority wearing hijabs, were sitting in the front row. There, looking directly up at me, were multiple avatars of my disapproving mother, about to remind me how shameful I was.

The ensuing performance was about as fun as your parents walking in on you having sex, and then staying to watch until you come. For a section in the show I sang a parodic ‘Why-Do-You-Hate-Me’ type number to my ex-boyfriend – but the boyfriend I was singing to was Allah. Throughout the routine, the women in front of me were using Allah’s name in a more God-fearing way – ‘Allah have mercy’ (in Arabic) seemed to be the most common refrain. Another highlight included a sketch in which I compare men praying in mosques to gay chemsex orgies. When I dared glance out in front of me, the mother of the group seemed to be repenting in prayer on my behalf. I started to ricochet around a mental labyrinth of paranoia, the censorious voices from my childhood chattering loudly in my mind. As my past enveloped me, the empowering armour of my drag began to dissolve rapidly. I stumbled over my lines, tripped on my heels – more than once – and even welled up onstage (which caused the eyelash glue to incinerate my cornea). The rest of the drag queens – as well as the audience – were white, so it felt as if the Muslim women and I were operating on a different plane of reality from everyone else, one where only we knew the laws.

Once the show finished, I sprinted backstage and threw up in a bin. My agent knew something was up and ran to the dressing room. I trembled as she hugged me, distressed at the offence I knew I’d caused. I felt like I was fourteen again, when my parents would tell me on a daily basis that my flamboyance was the root of their unhappiness. I’d worked so hard to create my drag utopia, and until that night, it had been my haven.

And then came the news I was dreading. The women, waiting outside the stage door, passed on a message to the usher: they wanted to see me.

Like a reincarnation of my teen-self, I shuffled off outside, with all the strength of a young seahorse adrift on an ocean current. Seven years after drag had liberated me, I was about to relearn that my liberated new identity required disciplinary action.

There they were, all lined up. The mother of the group, who was dressed head to toe in Islamic robes, stared down at the floor, refusing even to look at me. Great, I thought, she thinks I’m Satan. She whispered something in Arabic to her daughter that I couldn’t make out. As her daughter began speaking, I twitched with terror, like a defendant in court about to learn the jury’s verdict.

‘My mom’s super Muslim, yeah, so she’s a bit uneasy, but she wanted me to tell you that she thought you were amazing, and that you should be really proud.’ Not guilty. In my dumbfounded jubilation, I went to hug her mother, who quickly shifted, like a pigeon does when you suddenly kick the pavement.

‘Easy, my mom’s from Saudi Arabia and really Muslim, so she can’t hug you, but she thought it was so cool seeing a gay Muslim on a stage like that. She said she feels really proud to have been here.’

I explained how I believed they were cursing me throughout the show. It turns out their expressions were akin to a colloquial ‘Oh my God!’ uttered out of enjoyment. The young woman then held my hand, stared honestly into my eyes, and said: ‘But your song to Allah …’ Fuck. Guilty on some counts. ‘… it broke my heart. I’ve been there. Trust me, I’ve been there – I’m a woman living in Saudi Arabia. But the thing is, Glamrou – Allah loves you.’

And with that, the women said their goodbyes, their Muslim drapery billowing in the Scottish wind, floating away from me like a mystical collective of apparitions, as if the entire encounter might have been a hallucination. Now, in general these days, I find it very difficult to sob – my body rarely gives in to the urge (the only exception being when I watch families in whom I have no investment celebrate their loved ones on X Factor, which always gets me). But as the women disappeared from the stage door and into the alleyway leading out to the Edinburgh night, I stepped after them and collapsed against the wall, convulsing so hard that I gave myself a splitting headache. Once the sobbing subsided and I was back out of the matrix, I felt as if I’d emerged from some combination of an exorcism and a K-hole.

I’ll forever remember that night as the precise moment when, for the first time, all the different parts of my identity collided. I’ve spent my whole life feeling like I don’t belong. As a queer boy in Islam class, the threat of going to hell because of who I was inside was a very real and perpetual anxiety. Despite being able to leave the Middle East for a liberal Western education that afforded me numerous privileges and opportunities, I faced constant discrimination and prejudice when I won a place at Eton for two years (two of the worst of my life). I’ve lived between the Middle East and London, and have felt too gay for Iraqis, and too Iraqi for gays. My non-binary gender identity has meant that I don’t feel comfortable in most gendered spaces – gay male clubs, for instance – and I regularly feel out of place in my own male body, as though it doesn’t match up to who I am internally. For a long time, I felt as if I belonged under water, in a marine world with colours to rival the outfits of any RuPaul drag queen, where things flow freely, formlessly and without judgement, where difference is revealed to be the very fabric of this universe. On land I’ve felt like a suffocating beached whale, unable to swim to anyone or anywhere.

But that Edinburgh night, as the beautiful girl in the hijab held my hand and reassured me of Allah’s unconditional love and I stood in front of her in a sequin leotard and a melting face of sapphire glitter, I finally felt as if I belonged.

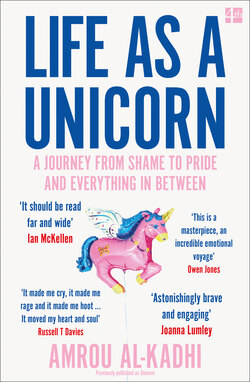

The December before that Edinburgh summer, I decided to get a unicorn tattooed across my chest. Christmas is one of the hardest periods for me every year; the months leading up to it are saturated with pictures of united families in green paper crowns beaming around the dinner table, and the dominant cultural narrative tells us that it’s the time to be with the real people who know and love us the most. Most friends of mine retreat to the houses they were raised in for cosy, Hallmark-worthy reunions, acquaintances post gifts from partners on Instagram, and it is the time I feel most divorced from Britain, the Middle East, my family, and, well, the world. So to keep me company for the holiday season, I invited a permanent-ink unicorn to live above my sternum.

I feel a great affinity with unicorns. They are the ultimate outsiders, destined to gallop alone. They share the body of a horse and are similar in form, but are of a different nature, almost able to belong in an equine herd, but utterly conspicuous and irrefutably other. For, no matter what, their fantastical horn cannot be concealed, signifying that they are of a different order entirely. In some medieval renderings of unicorns, the horns bring with them the sense of the pathetic; they are a deformity that invites the outside world to taunt the special being, almost like a dunce. As someone who has felt displaced for so long, I’ve harboured resentment for my own obtrusive horn, which has made it impossible for me to assimilate anywhere.

But as much as the horn is an unwelcome protrusion, perhaps even a social inconvenience, it is also a symbol of pride, of a creature flaunting its difference without shame. For the horn also tells us that the unicorn is a survivor, a rare and tenacious creature, ready to fight should its difference bring it in the way of violence. For me, the multiple meanings of unicorns encapsulate the very essence of being queer. Their identity challenges the status quo and is violated by the normative. They long to gallop in a herd, but struggle to ride to the rhythm of others. They can almost hide in plain sight, and yet are also unquestionably unique.

Like a unicorn, I’ve never been able to escape my difference from others. As someone who’s always existed between cultures, classes, genders, and racial groups, I have what society deems an ‘intersectional’ identity. The concept of ‘intersectionality’ refers to the fact that we cannot study the issues surrounding one oppressed social group without understanding its intersections with many others; for instance, it is superficial to have a feminism that dismantles systems of misogyny without also understanding how this intersects with structures of racism (when examining the wage gap for instance, it’s critical to consider not only the disparity between men and women, but the one between white women and women of colour). And, though mine is an extreme example of this, every person’s identity contains multiple facets that intersect with each other internally, and which are represented by intersecting political and social arguments in the outside world. Sometimes these intersections coexist peacefully; sometimes they are in conflict, and tear us into pieces.

My intersectional identity has never felt stable. The best way I can describe it is to say that it’s like playing a really exhausting game of Twister with yourself all day every day, a key part of your identity choke-holding you on one end of the flimsy plastic sheet, while you wrap your legs around its opponent on the other. All the various facets of my identity have pulled each other in polarising directions, leading at times to absurd contradictions, episodes of severe disorientation, and deep internal fractures.

The tattoo artist who gave me my unicorn is a wonderful queer practitioner called Jose Vigers. With an empathetic ear and unreserved generosity of spirit, Jose listened as I explained over Skype what unicorns meant to me. After some wonderfully collaborative discussions, we settled on the design that now armours my heart: a unicorn, being attacked with arrows, on the cusp of collapsing, but strengthened by a BDSM harness and its enduring fighting horn. I wanted a picture that relayed both fragility and strength: an image of a being whose very power and ability to survive derive from the pain they have suffered.

I hope that the story I am about to tell will paint a similar picture.