Читать книгу Learning to Die in London, 1380-1540 - Amy Appleford - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

_______________

Dying Generations

The Dance of Death

The Good Death of Richard Whittington

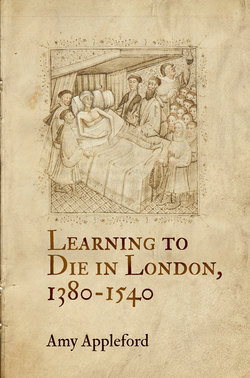

An image of the deathbed of Richard Whittington, wealthy merchant, important creditor to the Crown, and three times mayor of London, forms the frontispiece of the earliest copy of an English translation of the ordinances governing the Whittington almshouse, one of the institutions funded by his massive bequest (Figure 1). The ordinances were written in Latin and sealed by three of Whittington’s executors—John Coventry, William Grove, and John Carpenter—in December 1424, twenty months after the merchant’s death in March 1423 and shortly after work had been finished on the building both of the almshouse and of a closely related institution nearby.1 This was the college of priests, dedicated to the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, at St. Michael’s Paternoster, Whittington’s parish church, whose refurnishing and expansion he had supported during his lifetime and where he and his wife were buried. Along with a library at the Guildhall, the building complex where the city administration was located, these two institutions constituted the most spectacular manifestations of the series of high-profile death projects associated with Whittington’s name.

The English translation of the ordinances dates from 1442–43, almost two decades later than its Latin original and shortly after the death of the final executor, Carpenter, who, as the “common clerk” of the city from 1417 on, was by far the most important administrator of Whittington’s estate. The translation thus coincides with the moment, long anticipated by the Latin ordinances, when oversight of the entirety of the estate, including the college of priests and the almshouse, passed into the hands of the Mercers’ Company. This was the guild to which the former mayor and one of the executors, Coventry, belonged. As Anne Sutton argues, with its acquisition of the massive Whittington charity, the Mercers’ guild became the most powerful organization in London. The professionally written copy that contains the frontispiece image is likely to have been made for the new overseers in the mid-1440s as soon as the translation itself was complete. The frontispiece, a fine pen drawing by the prominent London “lymner” William Abell, confirms the book’s quasi-official status.2

FIGURE 1. Richard Whittington on his deathbed.

Ordinances for Whittington’s Almshouse, folio 1r. Courtesy of the Mercers’ Company.

Photograph by Louis Sinclair.

The drawing represents a dying Whittington in the act of commissioning the foundation of the almshouse. He is attended by his physician, in the background, who is confirming the imminence of his bodily dissolution by checking his urine; by his priest, possibly William Brooke, rector of St. Michael’s Paternoster and first master of Whittington college, who is standing composedly at his head on the bed’s farther side; and by various lay members of his household and local London community.3 These include thirteen bedesmen, representatives of the almshouse, clustering in rows toward and behind the bed foot; and two of the executors, Carpenter and Coventry, identified by names on their tunics and standing at the head of the bed across from the priest. However, the most prominent lay figure in the drawing, tall, bearded, and likewise identified by name, is the third executor, William Grove, a professional scribe active in London in the early part of the century. Grove, whose role here derives from the fact that he made the authoritative copy of the Latin ordinances, is pictured in silent colloquy with the dying man, the first in a chain of figures who successively mediate, implement, and benefit from Whittington’s charity. His hands for now devoid of writing instruments, Grove makes a gesture of acquiescence to Whittington’s gesture of command, looking sternly across the bed at Carpenter and Coventry, whose own hands in turn eagerly direct our (and perhaps Whittington’s) gaze toward the bedesmen and their first head tutor, Robert Chesterton. 4 With these bedesmen—their diminutive bodies partly hidden, their eyes turned gratefully toward their benefactor, their intercessions for his soul evoked by the rosary held in Chesterton’s right hand—the energetic foundation narrative represented by the scene reaches its denouement.

In certain ways, the scene depicted in the frontispiece to the English ordinances seems in tune with the shifts in the understanding and representation of death during the decades before and after 1400 described in the last chapter. Written in the 1380s as a vernacular supplement to the liturgical rite, the Ordo ad visitandum infirmorum, and based on two well-established Latin death texts, the A version of the Middle English Visitation of the Sick made possible a new level of informed participation by the non-Latinate dying person in the church’s last rites, at a moment when such participation was coming to seem theologically necessary. Produced at very nearly the same time, and still in circulation in early fifteenth-century London alongside other reformist texts, the more radically lay-oriented longer version of this text, Visitation E, went further, encouraging the idea that lay people could not only make an informed good death but help others to do so, too: even, if necessary, in the absence of the morally upright “trewe preest” it describes.

Like the deathbed rooms that had for centuries been the destination of solemn processions such as the one described in the Sarum rite, Whittington’s deathbed thus transforms the private room in which it is situated into a public space, crowded with the dying person’s “even-cristen.” Yet as is differently the case in both versions of The Visitation of the Sick, the center of gravity here has once again, in Abell’s representation, become emphatically lay. The priest is present, indeed ready at hand, and takes proper priority over the doctor, in accord with the ecclesiastical principle noted in the A version: “it is ordeined be the lawe that ther shal no leche ȝiven no bodily medicine to a seke man til he be helid gostli [spiritually healed], & that he have take gostli medicine, that is to sai, shrift & housel [confession and absolution].”5 But although the priest is at the bed, he is almost marginal, his eyes and hands taking no part in the gestures that link almost all the other figures, his place in Whittington’s line of vision crowded out by the scrivener Grove, the recorder of Whittington’s dying wishes. As is the case in Visitation A and more emphatically in Visitation E, much of the priest’s sacral authority has thus passed to the dying person, on this occasion the same paterfamilias whose role in the conduct of the deathbed is affirmed in the latter’s text and manuscript companions. In consequence, despite the drawing’s investment in the communitarian, the laicized space around the deathbed has become hierarchic, affirming both the householder’s authority over his “meynee [household]” and the fierce responsibilities that go with it. Though he is no longer able to help them personally to die, as does the householder in the Fyve Wyttes, and though he needs their prayers, Whittington still looks to their good from the throne of this deathbed, in part by requiring their submission to a unifying disciplinary regime.

In other respects, though, the frontispiece depiction of the famous dying merchant differs sharply from the model deathbeds considered so far. This is partly a matter of scale. Whittington’s well-governed household is massive, incorporating the almshouse, the college of priests, the Guildhall Library, and the London metropolis itself, and extending indefinitely through time as well as space. To exercise the mix of temporal and spiritual governance represented by the almshouse and its companion institution requires the energies of others over generations, not years. But there is also a qualitative difference. This deathbed belongs to a substantial urban merchant: a man whose worldly importance is wholly the result of his success in creating wealth. As a result, the drawing is necessarily deeply concerned with wealth and its relation to the soul’s salvation. The iconography of the drawing recalls that of the death of a monarch or a saint, surrounded not by royal kin or monastic brethren but by the aldermen and bureaucrats who carry out the dying man’s spectacular charitable work. Yet despite the drawing’s aura of sanctity, the dying man at its center is not depicted as focused on the next world, “nouȝt thenkynge … on thy richesse, but oonliche and stedefastliche on the passioun of owre lord Jhesu Crist,” as Visitation E enjoins, gazing at a cross held before his eyes or rehearsing the colloquy with God that goes with this gaze.6 Instead, his interests are all in this world: in an urban institution, its charitable mandate, its perpetuation, and its money.

From the perspective of this new deathbed, Visitation E appears idealistic, stripped down to its urgent focus on the moment of death and the mixture of penitence, control, and abandonment to the crucified Christ it requires. Instead of preparing affectively to face eternity, Whittington is practically focused on two temporal futures: his time in the intermediate realm of purgatory and the charitable foundations, starting with the almshouse itself, that will help shorten this time. The Visitation is silent on the matter of purgatory and specifically counsels the dying not to think on “on thy richesse.” But Whittington must above all else think on his riches: partly because, as a former civic leader and substantial business owner, he has an obligation to dispose of them well; partly because these riches, acquired through mercantile trade, put his salvation in peril if he does not think about them. “As in the myddel of a joynyng of stones a paele [staff], or a stake, ficchid [fixed] is, so bitwen the myddel of biyng and silling he shall ben anguysht with synnes,” declares Ecclesiasticus 27:2.7 If Whittington is finally to “legge” the “stoon” of his soul “in þe walle of þe citee of heven slighliche [carefully], with-owte eny noyse or stryf,” as Visitation E puts it,8 his preparation of this stone demands that he continue, until the last minute, to engage with the world.

In relation to the book of almshouse ordinances the frontispiece prefaces, the mixed religious, social, civic, and financial concerns signified by Whittington’s urgently pointing hand take us most obviously to the text of the ordinances themselves. Greeting “alle the trewe people of Cryste,” the ordinances indeed open with a kind of gloss on the image, in the form of a sententious statement of the devout pragmatism that brought the almshouse into existence:

The fervent desire and besy intension of a prudent, wise, and devoute man shold be to cast before [plan in advance] & make seure the state and th’ende of his short lyff with dedes of mercy and pite. And namely to provide for suche pouer persones whiche grevous penurie and cruelle fortune have oppressed and be not of power to gete their lyvyng, either by craft or by eny other bodily labour. Whereby that, at þe day of the last Jugement, he may take his part with hem [those] that shalle be saved. This considering devoutly, þe forsaid worthy & notable marchant Richard Whityngon, the whiche, while he leved, had right lyberalle and large handes to þe nedy and pouer people, charged streitly in his deth bed … to ordeyne an house of Almes after his deth, for perpetuell sustentacion of suche pouer people.9

Here Carpenter and his fellow executors, who voice the entire document as the fulfillment of Whittington’s “comendable wille and holsom desire,” represent the almshouse in the exemplary terms often used of the Whittington charity.10 The ordinances then go on to spell out, among other things, the almshouse’s physical extent and design, the moneys to be spent in the maintenance of the bedesmen, the prayers they must say each day for Whittington and his wife, and the behavior required of them as they live in Whittington’s foundation, in order that they may be worthy “after the ende of this liff” of the “hous of the kyngdom of heven whiche to pore folk is promist.”11 Following an old solution to the problem of merchant salvation, the ordinances show Whittington “slighliche” preparing his own soul-stone by preparing those of his poor beneficiaries, so that “at þe day of the last Jugement he may take his part with hem that shalle be saved,” smuggling himself into heaven with the “pore folk” who are its most legitimate heirs.

But simply because of the position of Abell’s elegant and thoughtful deathbed scene at the front of this apparently utilitarian text, Whittington’s pointing hand also directs us toward the other half of the frame, at the end of the book. Here the translator has written a brief envoy, in the form of a Chaucerian rhyme royal stanza, dedicating the translation and the book that contains it to the trustees of the Whittington estate and wardens of the Mercers’ guild for whom it was made, who in 1442–43 were John Olney, Geoffrey Feldyng, Geoffrey Boleyne, and John Burton (Figure 2):

FIGURE 2. Envoy.

Ordinances for Whittington’s almshouse, folio 15r. Courtesy of the Mercers’ Company.

Photograph by Louis Sinclair.

Go litel boke, go litel tregedie,

The[e] lowly submitting to al correccion

Of theym beyng maistres now of the Mercery,

Olney, Feldyng, Boleyne, and of Burton,

Hertily theym besekyng [beseeching], with humble salutacion,

The[e] to accepte and thus to take in gre [look with favor],

For ever to be a servant within þeire cominalte [community].12

The stanza’s points of literary reference are, of course, the envoy to Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, which has the same first line and directs the “bok” to be a humble “subgit” to “Virgile, Ovide, Omer, Lucan, and Stace,” before asking John Gower and Ralph Strode “to vouchen sauf, ther nede is, to correcte” the poem; and that of John Lydgate’s Troy Book, whose author tells his book to “submitte to … correccioun” and “put þe in þe grace” of its dedicatee, Henry V.13

As they close, the English ordinances may seem to move outside the discourse of theology, drawing on a secular poetics as they submit their account of the almshouse to the foundation’s new “conservatours” and inviting the reader to view Whittington’s charity through an overtly Trojan lens.14 However courtly their settings, Chaucer and Lydgate’s glittering cities offer ready parallels to fifteenth-century London: a city ruled by the urban laity and shaped in significant ways by the Whittington estate. If poets rebuild the Old Troy, Whittington, his executors, and Mercers build the new: “Troynovaunt,” the name by which late medieval Londoners proudly called their city.15 Together, the frontispiece and the envoy direct themselves toward the future as they memorialize the past, using image and word to preserve in cultural memory the protecting aura of the receding charismatic presence of the founder, Whittington, by enrolling him perpetually in a house of fame.16 More, this house of fame is not built, as in a literary text, with words but with solidly supported mortar and stone.

But in describing the ordinances as a “tregedie,” the envoy also does something more searching, by acknowledging the indissoluble connection between Whittington’s deathbed and Fortune: a theme Maura Nolan shows was a central preoccupation of fifteenth-century vernacular public culture and that we will see had important theological, as well as ethical, resonances in a city given over to trade.17 Richard Whittington is memorialized as a tragic hero, a great but imitable man who through his charitable bequests countered “the dedes of Fortune, that with an unwar [unanticipated] strook overtorneth realmes of grete noblye,” as Chaucer, scion of a London merchant family, puts it in his Boece.18 Merchants had a special relationship with the concept of fortune, both practically in the day-to-day business of speculation and in coping with the vagaries of a market economy. Theorized as “risk,” the concept that differentiates legitimate trade from sinful usury, fortune was also central to the theological justification of their business. It is fortune that entitles merchants to profit from objects bought and later sold unaltered, because the act of storing these goods is “accompanied by the risk” of damage, fire, or robbery, subjecting them to the general “uncertainty about what may happen in the future,” as the Franciscan theologian Alexander of Hales puts it in his discussion of the temporal dimension of mercantile activity.19

Ending on its elegiac Trojan note, the envoy invites us to imagine Whittington staring down from heaven, with Chaucer’s hero Troilus, at “this litel spot of erthe that with the se / Embraced is,” learning to “despise / This wrecched world” as “vanite / To respect of the pleyn felicite / That is in hevene above,” and so completing the realignment of his interests from the earthly to the heavenly, the fortunate (“wrecched world”) to the felicitous (“pleyn felicite”), in a manner not possible while he was still alive. But where Troilus, representative of a different theological economy, can “lough right at the wo / Of hem that wepten for his deth so faste,” 20 Whittington needs the tears that Troilus despises, and the vigorous continuance of mercantile activity that the names of the “maistres now of the Mercery, / Olney, Feldyng, Boleyne, and of Burton” represent. At least in the minds and prayers of its living inhabitants, Whittington’s soul remains perpetually connected with the ever-changing fortunes of his institutions and of his city.

In a world more complicated by trade, profit, and the temporal rewards and spiritual dangers they bring than the Visitation of the Sick can acknowledge, how does a merchant die a good death? In early fifteenth-century London, a city built and constantly rebuilt on the profits of trade, this was a question not only for the superrich like Whittington but for inhabitants from almost all the diversity of professions necessitated and sustained by urban living: a question indeed pressing enough to be a matter of institutional concern to governors of the city itself. As this chapter argues, it was also a question whose answers had developed as fast as the cityscape, and in conjunction with it. According to Piers Plowman, a late fourteenth-century poem with close ties to London, a merchant who would be saved must use his winnings to “amende mesondieux” (hospitals) and repair broken roads and bridges, and assist in maintaining Christian community by providing several categories of the needy with the means to prosper:

Marien maydenes or maken hem nonnes;

Povere peple and prisons fynden hem hir [them their] foode,

And sette scolers to scole, or to som oþere craftes;

Releve Religion and renten [endow] hem bettre.21

Helping young women, the poor, prisoners, students, and monks to live as they ought, merchants exercise the corporal works of mercy discussed in the last chapter in specifically financial ways.

Fifty years later this solution was still relevant, as the Whittington almshouse shows. But just as the role of the layperson on and around the deathbed changed as spiritual responsibility passed into the hands of the laity, so answers to the problem of merchant salvation changed also. In its investments in a purgatorial economy, the almshouse, which is discussed in the next section of this chapter, is a traditional mercantile death project, although with contemporary updates and the conscious exemplarity that is a feature of all the Whittington projects. But this is not true of other institutions developed in Whittington’s name, including the college of priests founded next to the almshouse: an institution only loosely related to “Religion” in the monastic sense in which Langland uses this term. Langland imagines merchants “in þe margyne” of Christian society.22 Under what was almost certainly the careful moral and intellectual as well as legal guidance of John Carpenter, who as common clerk amassed a private library of theology, ethics, and advice literature that Caroline Barron calls “one of the most extensive … to be found in fifteenth-century London,” the Whittington institutions place merchants and their associates at the center, taking charge of their own and others’ religious education in just the way that Visitation E suggests a privileged layman should.23

Yet if reformed religiosity provided part of the backdrop to the merchant “good death,” it had too little to say about the immersion in fortune that was merchant life, or about the temporal in general, to provide a comprehensive guide to the concerns raised by wealth for dying merchants like Whittington, for whom Carpenter had spiritual responsibility as executor. Nor, in particular, could it address many of Carpenter’s wider concerns as a professional and deeply devout common clerk, responsible for the good governance of a city whose corporate survival depended on its ability to outlive the individual bodies of its members, “dying generations” all.24 The third section of the chapter thus considers some other possibilities enabled by the intimate relationship between mortality and temporal and spiritual government I am arguing to be a strong thread of late medieval death discourse, linked to Carpenter and the seat of city government, the Guildhall, with its cadre of legally trained lay clerics. These possibilities include the purely administrative solution Carpenter offers to the problem of death in the Liber albus and the formal concern shown in his will for the decorous ritual commemoration of London’s wealthy dead: part of a strong ethical commitment to the city’s past balanced by the will’s equal commitment to its future. They also include a Christian humanist strand of thinking about living and dying well, known to Carpenter through his personal copy of Petrarch’s De remediis utriusque fortunae and somewhat distinct from the “reformist” discourse that has held center stage to this point.

The great early fifteenth-century London manifestation of this second strand of death discourse, the subject of the final section of the chapter, was the Daunce of Poulys or Dance of Death, a civic art project for which Carpenter, probably acting in his capacity as common clerk, seems to have been responsible. An idealized image of Christian London, the sequence of individualized deaths of which the work consists takes us back generically to the tragic and thematically to the fortunate. For while the Daunce of Poulys is in some ways aligned with the laicized reformist religiosity of Visitation E, its reach is not only toward the transcendent but also toward the living, the social, the corporeal, and the material—with what dies in a death, as well as what was believed to survive it. Through this dual purpose, the work can engage more closely than other kinds of reformist religiosity with the issues surrounding worldly engagement itself. In the process, it provides a tool not only of self-government and the government of the household but of civic government, reinforcing a view of the city as a dance in which all the estates of society join together even as their carefully articulated professional identities remain separate. Opening with the good death of a privileged man and its institutional and literary consequences, the chapter ends with a representation of the good death of London as a whole.

The Whittington Almshouse

Come ȝe, the blessid of my fadir, take ȝe in possessioun the kyngdoom maad redi to ȝou fro the makyng of the world. For Y hungride, and ȝe ȝaven [gave] me to ete; Y thristide, and ȝe ȝaven me to drynke; Y was herboreles [shelterless], and ȝe herboriden me; nakid, and ȝe hiliden me; siik, and ȝe visitiden me; Y was in prisoun, and ȝe camen to me.

(Matthew 25:35–36)25

The almshouse, the late medieval successor of the hospital, Langland’s “mesondieux,” has links to almost all the deeds Christ describes as criteria for salvation and, perhaps for this reason, had special attraction for late medieval English merchants. As R. M. Clay demonstrates in her classic study of medieval hospitals, it was the “old merchant princes” or prominent townsfolk who were responsible for most of the houses for the poor built in the late medieval period.26 The Whittington almshouse has been evoked in discussions of changing attitudes toward the poor in late medieval England, as evidence of an increased desire for social control inherent in alms being given only to the “deserving” poor; and, indeed, the ordinances emphasize that only “discrete and humble” poor should be admitted to the house.27 But more significantly, the ordinances’ main emphasis is that the community should be made up primarily of those Londoners who have been brought low through no fault of their own but by fortune’s whim. The house is “namely [especially] to provide for suche pouer persones whiche grevous penurie and cruelle fortune have oppressed and be not of power to gete their lyvyng either by craft or by eny other bodily labour,” whose difficult lives might be described through the language of “tregedie” used in the ordinances envoy.28 Working daily in a culture of exchange, competition, and speculation, London merchants knew well the ups and downs of fortune. As was also true of the gifts of money and food to those who got behind on their payments serving time in Ludgate, the debtors’ jail, another popular civic choice of almsgiving, there is a significant element of recognition between the “merchant prince” founders of almshouses and their inmates.

The efficiency of the almshouse form as a way of fulfilling the corporal works of mercy may in part explain its attraction for London merchants and merchant guilds. But almshouses also have a specific relationship to issues of mercantile profit and Christian morality. As the anxiety expressed by Piers Plowman about mercantile salvation suggests, the figure of the merchant had long been disruptive of traditional estate models of medieval society, not least because he was associated with the sin of usury: the sin of “selling time” or “making gold breed” through buying goods and selling them at a profit. Providing for the poor was a particularly effective means by which merchants could raise their moral profile. In order to be both just and merciful, the successful merchant, such as Whittington, needed to recirculate his enormous wealth back into the common good, because, as theologians such as Aquinas argued, “according to natural law goods that are held in superabundance by some people should be used for the maintenance of the poor.” Riches not put back into public circulation are tantamount to stolen goods: “It is the bread of the poor which you are holding back; it is the clothes of the naked which you are hoarding; it is the relief and liberation of the wretched which you are thwarting by burying your money away,” he adds.29 The institution of the almshouse by Whittington’s executors gave concrete form to the idea that the wealthy merchant is a mere steward of his property and riches in the same way bishops, abbots, and monks are stewards of the collective Christian wealth of the great monastic and secular religious foundations. As the author of the early fifteenth-century Dives and Pauper has the Pauper figure explain, “alle þat þe ryche man hat pasynge hys honest lyvynge aftir þe degre of hys dispensacioun [disposable wealth], it is oþir mennys & nout hese [not his], & he schal ȝevyn wol harde rekenyng [a very strict accounting] þerof at þe dom [Judgment]…. For riche men and lordys in þis world ben Godys balyys [bailiffs] & Godys revys [reeves] to ordeynyn [provide] for þe pore folc & for to susteynyn þe pore folc.”30 The almshouse foundation redistributes Whittington’s surplus wealth back into the London community by means of “visible participation in an economic logic … that had both a sense of civic solidarity and mystic unification.”31 The Whittington almshouse thus fits into a traditional pattern, one with its origins in patristic and scholastic work on the “problem” of excess wealth, private property, and mercantile exchange.

However, although much of the theological logic expressed by the Whittington almshouse had been worked out in full by the thirteenth century, in several respects it remains a consciously innovative project: one indeed typical of Whittington projects in the thoroughness with which it rearticulates existing institutional and ethical models along specifically fifteenth-century lines. According to the ordinances this is true, first, of how it understands and treats its beneficiaries. On the one hand, the inhabitants of “goddeshowse or Almeshous or the Hospitall of Richard Whittington”—”of men alonly [only] or of men or wommen to giddre after the sadde discrecion & good conscience of Th’overseers”32—are enjoined to behave as traditional recipients of charity, living like members of any semireligious community and praying often for their founders. “Nedye, devowte and honeste in Conversation and Lyvinge,”33 they are to reside in the house, wear its uniform, eat meals together, submit to fines if they misbehave, attend several services a day, and say prayers, alone and together, for their benefactors—including Whittington and his parents, his wife, Alice, and her parents, and Whittington’s own early patrons, Richard II and Thomas of Woodstock.34 After compline, the whole community must gather at the tomb of Whittington and his wife in the church to “sey for the soules of alle cristen people” the De profundis and other prayers, ending with “God have mercy on oure founders soules and alle cristen,” said “openly in Englissh.”35 Besides being under the pastoral care of the college and its master, the bedesmen are under the moral, as well as practical, control of their own tutor, chosen by the “conservatours,” first the executors, later the “maistres,” of the Mercers’ guild. Exercising the quasi-sacerdotal role of teacher by word and example, the tutor is charged to be zealous “to edifie and norissh charite & peas amonge his felawes and also to shew, with alle besinesse bothe in word and deed, ensamples of clennesse and vertue.”36 A good deal is done, that is, to ensure that these “pouer persones” on whose prayers Whittington’s soul depends and for whose own souls he still shares responsibility from beyond the grave act the role of the patient poor as they should.

On the other hand, the detailed arrangements made for the bedesmen are also suggestive of a concern to emphasize their personal spiritual responsibility, to treat them as agents, not patients. Not only do they have freedom to move around the city and spend most of their time as they please, their individual living arrangements are not monastic or semireligious but collegiate or, perhaps, Carthusian. While it is the duty of any bedesmen “myghty and hole of body” to minister to the “seke and feble” in any way that may be necessary, each bedesman lives alone, with a fireplace, latrine, and other domestic appurtenances. Moreover, the almshouse is expected to provide various kinds of space for contemplative retirement: “Also, we woll and ordeyn that every persone of hem now Tutor and pouer folk and successours have a place by him self within the seid Almeshous. That is to sey a Celle or a litell house with a chymene and a pryvey and other necessaries in the whiche he shalle lyegge and rest…. Whan they be in hir forseid houses or Celles aforeseid and also in the cloistres and other places of the seid almeshouse have hem self quietly and pesably, without noise or disturbance of his felawes, and that they occupie hem self in prayer or reding or in labor of hir hondes or in som other honest occupacion.”37 Apart from enjoining them to use the very simple Psalter of Our Lady (“thries L [three times fifty] Ave maria with xv pater noster and iij Credes”)38 in praying for their patrons, the ordinances do not lay out any spiritual regime for the bedesmen, who in practice included “pouer folk” from a range of social backgrounds, unsuccessful members of the Mercers’ guild, retired choristers and lay clerks from St. Michael’s, and others, some of them with very limited literacy.39 But alongside the well-established arrangements for a traditional, disciplined lay community of the poor, these more novel arrangements build into the institution a set of assumptions about the need for individual spiritual self-government that we have seen to be a hallmark of the death discourse of the period. Whittington’s role as paterfamilias of the almshouse and its inhabitants is not only to care for their temporal and eternal needs but to give them the chance to exercise care over their own souls, to take responsibility not only for maintaining the communitarian values of peace, love, and “cheritee,” but for themselves.

The second innovative feature of the Whittington almshouse also concerns laicization, for the institution is well known among historians of philanthropy as one of England’s earliest “secular” charitable institutions, whose creation and administration remained in lay, not ecclesiastic, hands.40 The ordinances give various roles to the nearby college of priests and its master, who say daily services in St. Michael’s Paternoster, lead the prayers for the souls of the benefactors, and have the right to fill every seventh vacancy at the almshouse.41 But whereas before the fifteenth century most hospitals for the poor were under direct supervision by clergy or Augustinian canons,42 here full control of the almshouse remains, first, with John Carpenter as lead executor, later with the “conservatours” (the Mercers’ guild).43 Ecclesiastical involvement in the day-to-day running of the almshouse is kept to a minimum.

As with most projects connected to the Whittington estate, the specific arrangements that allowed the almhouse to retain its lay status were the business of John Carpenter, whose prompt pursuance of a charter of incorporation for the almshouse provided one of the legal instruments by which Whittington’s private riches were translated, as the theology of almsgiving demanded, into communal wealth. In 1432, soon after finally settling its endowment, Carpenter obtained a foundation charter for the almshouse from the Crown, making it into a legal “person,” empowered to hold property in perpetual succession: one of the first nonreligious institutions in England to use this juridical tool.44 Carpenter’s incorporation protected the almshouse from the possibility that the Mercers might one day seek to sell it piecemeal, or that its moneys might be alienated by a sovereign strapped for funds. Allowing the almshouse to dispense with the expensive need for the license usually required when wealth passed from private individuals into the hands of a perpetual body, this “mortmain” arrangement also allowed the almshouse to profit from the good deaths of future merchants, duly dispersing their own winnings to the poor through this institutionalized form of the works of mercy.45 Finally, it allowed Carpenter to invest the bedesmen with a measure of formal control over the institution’s legal status, as expressed by the keeping of the charter of incorporation and the common seal within the house itself: “We wille and ordeyne also that the seid Tutor and pour folke have a comyn chest and a Comyn seale in whiche chest thei shalle putte the said Seal. Also their chartres, lettres, privilegis, Escrites, and Tresour of theire seid house and other thinges whiche shalle seme to the seid Tutor and pouer folk expedient for the commyn profit of the seid place; whiche chest we wille be put in a secreet and a sekir [secure] place with ynne the boundes of the seid hous.” The chest was to have three keys: one held by the tutor, one by the eldest member of the house, the third by “oon of the othir felawes of the seid Almeshous every yere to be new chosen by us while we lyve, and after our discesse by the maisters of the Mercerie.”46 This system parallels similar arrangements not only at the London Guildhall and at Oxford and Cambridge colleges but also at the Whittington college of priests, emphasizing the separateness of the two institutions from a jurisdictional point of view, and thus the exclusively spiritual nature of the care exercised by the members of the college over the bedesmen next door. In 1410, only a little over a decade before the almshouse was founded, a set of polemical Lollard petitions had been presented in the House of Commons arguing that almshouses should be placed under the “oversiht of goode and trewe sekulers,” since “preestes and clerkes … have full nyh [very nearly] distroyed all the houses off almesse withinne the rewne.”47 Although the Whittington almshouse was created with private money, not through the ecclesiastical disendowment advocated by the Lollard petitions, and although it is far from expressing their virulent anticlericalism, Carpenter’s careful legal arrangements appear to reflect a similar view of how institutions of this kind should be managed.

As an engine of prayer and exclusive mausoleum for London’s richest citizen, the Whittington almshouse is in another sense an explicitly anti-Lollard project, for the Lollard understanding of how almshouses should work is aggressively antihierarchic and communitarian. According to the seventh of the “Twelve Conclusions,” presented to Parliament and nailed to the door of St. Paul’s and Westminster Abbey in 1395, in contemporary England “special preyeris for dede men soulis mad in oure chirche preferryng on be name [one by name] more þan anothir”—a system on which “alle almes houses of Ingelond ben wikkidly i-groundid”—represents a “false ground of almesse dede.” Instead of being the economic product of a private arrangement founded in mutual self-interest, “þe preyere of value” should spring “out of perfyth charite” and “enbrace in general alle þo [those] þat God wolde have savid,” not small groups of privileged individuals.48 The daily prayers said at the services in St. Michael’s and at the Whittington tombstone enfold “the soules of alle cristen people”—a broader formulation than the Lollard “alle þo þat God wolde have savid”—and by enriching the city’s liturgical round, more generally “augment the divine cult” to the same end.49 But a key feature of all the Whittington death projects as articulated by Carpenter and his fellow executors is their repeated linkage of works of charity with his exemplary and singular name. During the 1420s and 1430s, the Whittington arms appeared as a sign of his charity in buildings all across the city, from the almshouse and college themselves to various locations at the Guildhall, to a chantry chapel at St. Paul’s, to the south gate of St. Bartholomew’s hospital, where they were placed near a stained glass window representing the seven works of bodily mercy.50 These emblems serve a hortatory function, as signs of the enduring, virtuous presence of a figure who was represented as effectively London’s new founding father. But they also appeal, mutely, for the prayers of London’s citizens, turning the entire community, from one perspective, into a giant chantry or almshouse dedicated to the salvation of a single individual.

However, the third and most innovative feature of the Whittington almshouse, its close ties to an ambitious college of secular priests, goes a long way toward addressing Lollard attacks on private charity, even as it associates the institution with what became one of London’s most powerful engines of reformist orthodoxy. Whittington college, which was run under the same general structure of lay oversight as the almshouse, was envisaged partly as a place of prayer for the souls of Whittington and his wife, composed like a large chantry chapel of “five or six perpetual chaplains” under a master, partly as an adjunct and spiritual support to the almshouse as it carried out its fundamentally similar purpose.51 But it was stipulated from the start that the priests be highly educated as well as virtuous (“viris bene literatis et virtuosis”) and that the master, ex officio rector of the parish and obliged to be resident, be a doctor of divinity (“in sacra theologia graduatum”), thus adding St. Michael’s Paternoster to the growing group of London parishes in the spiritual care of advanced graduates of Oxford or Cambridge, who, especially from the 1430s on, formed part of the church’s first line of defense against Lollardy in the nation’s capital.52

It appears to have taken some time to find a master who met this qualification.53 A few years after its foundation, however, the college was fortunate enough to attract—perhaps through Carpenter’s well-connected relative also called John Carpenter, master of the hospital of St. Anthony’s of Vienne on Threadneedle Street, later bishop of Worcester54—the first in a tightly knit series of three brilliant masters, all from outside London, who successively positioned themselves at the center of efforts to promote the religious education of lay Londoners, not just in their immediate environs but throughout the city.55 This was the vigorously evangelical Reginald Pecock, always anxious (as he states in his Donet) to be “a profitable procutoure to lay men” by communicating religious truth through his own vernacular books, some of which may have been written while he was at the college and which are shot through with references to the spaces and rituals of London and to the Mercers themselves.56 Pecock’s defense of orthodoxy against the biblicism of the Lollards, with their seductive claim (as he puts it in The Repressor of Over Much Blaming of the Clergy) that “whate ever Cristen man or womman be meke in spirit … schal without fail and defaut fynde the trewe undirstonding of Holi Scripture,” worked by promulgating a carefully stepped program of education aimed at the universal human faculty of the reason and thus in principle accessible to the laity, as to others.57 Although Pecock does not specify its intended readership in detail, the title of one of his books, the Pore Men’s Mirror, written for “þe persone poorist in haver [possession] and in witt,” exploits his public position as the curate of poor bedesmen and could have been designed for reading at the almshouse.58 Whether or not this is so, the premise of his entire vernacular oeuvre, that individual laypeople at all levels of wealth and education need to be equipped to understand church doctrine and ethics for themselves, is congruent with the principle of lay spiritual self-governance represented by the almshouse’s architecture, regime, and institutional arrangements. The theological controversies that finally brought him down derive from his later years as a bishop in the 1450s, by which time his emphasis on lay spiritual self-care may have been coming to seem radical.59 But in much of his surviving work Pecock writes as a Londoner and master of the college, working within the nexus of the alliance between civic authority and priestly learning that Whittington’s project enabled.

Both Pecock’s successors, Thomas Eborall (Eyburhale), master from 1444, and William Ive, master from 1464, were also concerned with the defense of orthodoxy. Eborall was a member of a 1452 commission to examine for heresy works belonging to Andrew Teye; according to a note in one manuscript of the Wycliffite New Testament, “doctor Thomas Ebborall and doctor Yve” were both asked to “oversee and read” the book “or þat [before] my modir bought hit.” Eborall also defended himself and other London rectors against the attacks his predecessor, Pecock, launched against the powerful civic preaching culture of the 1440s: the first of a number of incidents, shortly after Carpenter’s death, in which the anti-Lollard orthodoxy embodied by the college and, more generally, the city’s educated secular clergy turned on itself.60 Ive was involved in the later investigation of Pecock’s theology that led to the latter’s condemnation for heresy, as well as in the defense, with Eborall and others, of the orthodox view of Church custodianship of Christian possessions against a strong challenge from the London Carmelites.61 Surviving items from Eborall’s library show his self-understanding as an upholder of civic orthodoxy and interest in the craft of preaching and in vernacular instruction, two other concerns shared by both men.62 Eborall owned a copy of the fourteenth-century compilation Pore Caitif, as did Carpenter’s friend John Colop: the devout stationer at the heart of the scheme to circulate books of vernacular theology among the laity for “common profit” through deathbed bequests, who lived his last years on Whittington’s properties next to the college. Like the Pore Men’s Mirror, Pore Caitif, which offers to “teche simple men and wymmen of gode wille the right way to hevene … withouten multiplicacion of many bokes” by providing a stepped spiritual education beginning “atte grounde of helthe, that is Cristen mennes bileve,” is of clear relevance to the officially poor almshouse bedesmen.63

Through its sister foundation, the college of priests, the spiritual reach of the almshouse was thus broader than its private focus on Whittington’s soul would suggest, reaching out beyond the carefully selected group of poor folk in the almshouse and the parish of St. Michael’s Paternoster to become a spiritual resource for the entire city. Its members supposedly especially learned and chaste, the college became part of a larger movement, headed by substantial lay Londoners such as Carpenter and the other Whittington executors, to nurture and reform pastoral care in the city, to affirm orthodoxy, and to combat heresy by sustaining the “trewe preestis” the author of the E Visitation imagines as worthy to hear a dying person’s confession. The heart of the reformist religious and literary culture of the city from its inception into the second half of the century, Whittington college represents an extraordinary public answer to the charge of spiritual selfishness leveled against “wikkidly i-groundid” almshouses by the “Twelve Conclusions,” to the call for a disinterested, “parfyth charite” that accompanied the charge, and to Wycliffite radicalism itself. Here, the legitimate but perilous financial surplus at the heart of the merchant enterprise finds its ambitious charitable outlet not in the bodily works of mercy but the spiritual ones, not only in prayers but in preaching. Whittington’s money is poured out not prudently, for the benefit of his own soul and the souls of his bedesmen, but evangelically and in “parfyth charite,” to enrich the intellectual and spiritual fabric of the whole of London.

The London Guildhall

The Whittington almshouse and its neighboring college thus offer one careful answer to the question of how a London citizen should die. The answer is grounded in traditional theology and institutions in ways that had come under fierce reformist criticism a generation earlier: in Whittington’s responsibilities to enrich his parish church; his responsibility to recirculate his wealth to the poor from whom, ethically speaking, it had been borrowed; the spiritual benefits of posthumous works of mercy; and the efficacy of the prayers of his beneficiaries, both bedesmen and priests at the college in their capacity as chantry priests, in speeding him through purgatory. On this ground, however, Carpenter and the other executors built an innovative foundation that affirmed two specifically contemporary religious ideals: the responsibility even of poor Christians of limited education to see to their own spiritual destinies; and that of the wealthy lay paterfamilias to concern himself with the spiritual, as well as temporal, governance of his household, in this case very widely construed as comprising, potentially, the whole populace. Through the writings of Pecock, the preaching of Eborall and Ive, and the responsibility all three men took for the city’s orthodoxy, part of Whittington’s surplus wealth was translated into works of preaching and teaching still visibly under his auspices. The Whittington arms became a marker not only of the city’s prosperity and of its concern to yield a spiritual account of that prosperity through the institution-building performance of the works of bodily mercy but of a zealous reformist orthodoxy.

Despite the absence of specific attention paid the problem of merchant wealth in Visitation E and its manuscript companions, a general affinity between the Whittington almshouse project and the theological and pedagogical priorities of these works is unmistakable. Indeed, one of the three copies of Visitation E that I discussed as household miscellanies in the previous chapter, Bodley 938, copied by one of the scribes of John Colop’s “common profit” book, Cambridge University Library MS Ff.6.31, has at least this indirect link to the almshouse. Many of the shorter works in Bodley 938, such as the Schort Reule of Lif, the expositions of the Paternoster, and Visitation E itself, make obvious sense within the ambit of the almshouse.64

In discharging his religious responsibilities as Whittington’s executor, then, Carpenter worked within an ethical paradigm in which virtuous acts are understood in relation to their final, eternal, purposes. This is clearly true of the almshouse and college, directed at the salvation, by more than one means, both of Whittington and of the citizenry of London. It is true of the other large project associated with the Whittington foundation: the library it was used to create at the Guildhall, within the complex that housed the city government, which collected mainly religious materials for the use of the city’s secular clergy and educated lay citizens. Carpenter took a special interest in this library, administering it personally and leaving it an unknown number of books in his will with twenty shillings to the bishop of London, Robert Gilbert, only if he had the will proved without taking a formal inventory of “goods and chattels.”65 It is true of a number of smaller projects—for example, Carpenter’s reestablishment, through the Whittington estate, of a decayed chantry chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary facing St. Paul’s at the northeast corner of the churchyard and situated above a charnel containing centuries of remains of London citizens and the tombs of three mayors.66 In an extended sense, it is even true of the Whittington estate’s contributions to secular building projects, such as the major expansion of the Guildhall itself that made its main hall, home of the city’s Court of Husting, one of the largest in the country, second only to Westminster. Signed as a Whittington project by the incorporation of his arms into the stained glass windows of the new mayoral courtroom, the new building had as its “public face” an elaborate porch at its south end, graced with sculptures of Christ as ruler, overseeing Law and Learning as they in turn oversee female figures representing the cardinal virtues trampling their contrary vices.67 Mayoral justice, its role the maintenance of Discipline, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance, thus becomes a manifestation of divine justice, whose end is not civic but eternal order;68 Whittington, as always under the posthumous auspices of his great promoter, Carpenter, affirms the city’s identity as a representation not only of Troynovaunt but of the city in which he hopes to lay his own stone, once it has been sufficiently polished through penitential almsgiving, the New Jerusalem.

Yet Carpenter’s engagements with the questions surrounding the civic good death did not end with his activities as Whittington’s executor, or even with the scrupulous arrangements he made for his own death, as reflected in his will. As London’s common clerk for over twenty years, the heart of the city’s government and the head of the cadre of clerks that constituted a key part of its staff, he also had other opportunities to engage with the ideas and ideals associated with death, and to use them toward the city’s institutional, moral, spiritual, and artistic enrichment, as well as, more concretely, its perpetuation. As we saw, the envoy of the English translation of the almshouse ordinances represents Whittington’s death as a “tregedie” and in so doing imagines the foundation under the complex sign of Fortuna. Fortuna was the threatening benefactor of a city of enormous wealth, divided into competing, loud, and often violent interest groups: a city still struggling to replace the population lost in the decimation of the fourteenth-century plagues; worried about storms at sea, price competition, and international shipping routes; worried, also, about the eternal implications of its worldly success; and all too aware that its liberties, granted by William the Conqueror, were held at the pleasure of the Crown.69

Just as the eternal fate of Whittington was the spiritual responsibility of Carpenter and his fellow executors, so the worldly fate of London was the professional responsibility of Carpenter and his fellow Guildhall clerks, a well-salaried and educated group whose office, in existence in some form since the early days of the city commune, saw to the day-to-day running of the city and its court, and the copying and preservation of the documents on which its power and longevity depended.70 Unlike the mayor and sheriffs, who were all elected annually, the city clerks had career tenure: as record keepers and senior officials, the clerks worked in the newly enlarged government building and constituted the city’s institutional memory.71 In this sense they differed from the royal clerks such as Thomas Hoccleve, whose concerns are often seen as typifying the “emergent bureaucratic class” of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, whose Westminster offices were no longer physically part of the king’s household, whose professional ambitions and hopes of patronage often went unrealized as a result, and whose salaries were constantly in arrears.72 As a short poem by Hoccleve, which begs Carpenter’s help in managing his messy financial affairs, allows us to infer, the city clerks’ relationship to power and money tended to be practical and managerial, focused on the smooth running of a mercantile community that by definition could not take Boethius’s advice and step off fortune’s wheel:

See heer my maistre Carpenter, I yow preye,

How many chalenges [claims] ageyn me be;

And I may nat delivre hem [pay them] by no weye,

So me werreyeth [wars against me] coynes scarsetee,

That ny [near] Cousin is to necessitee;

For why [for which reason] unto yow seeke I for refut [refuge],

Which þat of confort am ny destitut.73

The royal clerks at the Chancery and the Privy Seal are notable, among other things, for their consolidation and elaboration of a Chaucerian and broadly secular poetics, in response, so Ethan Knapp argues, to their precarious career of dependence on the turbulent dynamics of the court.74 The intellectual and literary culture of the two groups overlapped, not least in their joint concern for the relationship between permanence and impermanence, textuality, fortune, and death. Nonetheless, the writing, book ownership, and poetic patronage associated with the city clerks at the Guildhall has a different, institutionally more grounded and philosophically confident flavor.75

The best-known product of the textual culture of the early fifteenth-century Guildhall, giving one account of its attitude to such themes, is Carpenter’s main surviving written work, the massive Liber albus: a compilation of the city’s customs produced in 1419–21, early in his career as common clerk, some two years before he was appointed Whittington’s executor.76 Perhaps produced in emulation of the Liber Horn, by Andrew Horn, the early fourteenth-century city chamberlain who was Carpenter’s most ambitious predecessor in the Guildhall bureaucracy, the Liber albus is an exhaustive attempt to organize all the archival material surviving since the founding of London; to set down the customs of the city, as they pertain to the distribution and passing on of power in the city’s government; and to detail the history and duties of the elected governors and officials who make up the civic hierarchy. Before this project was undertaken during Whittington’s final term as mayor, Carpenter notes in his prohemium, many of the city’s customs had been written down “without order or arrangement,” or in some instances not at all, rendering them constantly vulnerable to the unexpected and irresistible power of death. Because “the fallibility of human memory and the shortness of life do not allow us to gain an accurate knowledge of everything that deserves remembrance,” unless knowledge is recorded in highly codified form, and because death often comes suddenly to the “aged, most experienced, and most discreet rulers of the royal City of London,” causing disruption to their successors, it is crucial to have in writing the details of the city’s elaborate ritual and legal life.77 Civic violence, such as had broken out on several occasions during the 1380s, threatens from within; impingement on the city’s liberties, especially on the part of church and Crown, threatens from without. If London, whose nickname Troynovaunt signifies its perpetual peril as well as its glory, is to stave off the fate of its ancestor, proper procedure must be visibly and repetitively followed in elections, legal proceedings, and the many processions through the city by which the mayor and his retinue physically affirmed its prerogatives. According to the Liber albus, given the deaths of the individual bodies who take part in these rituals, only a depersonalized, abstracted, and scrupulously cross-referenced set of written records can ensure the perpetual survival, across a series of “dying generations,” of the city as a corporate body.

Taken on its own, the Liber albus suggests a potent but also a narrow and secular understanding of death as a civic theme and of Carpenter’s professional relationship to that theme. Yet it is clear from the rebuilt Guildhall itself, with its theological library, its college of priests, and its iconographic representation of the heavenly roots of mayoral justice over its south porch, that the group of lay city clerks headed by Carpenter had a more capacious sense of civic textuality than this book suggests. If we look at a second document that reflects a different aspect of the textual culture of the city clerks, Carpenter’s will, written twenty years after the Liber albus, presumably in the early 1440s, we get a broader picture of his concerns and those of his most important textual community. In the process, we also encounter a discourse of death that has somewhat different roots from the reformist discourse associated with The Visitation of the Sick and similar texts, one whose combination of worldly and transcendent interests, shaped by early Christian humanism, makes it peculiarly suitable to the mercantile civic culture of London.

Aside from detailing his funeral arrangements and listing moneys and goods to be given to his wife, Katherine, his relatives, and his extensive household, Carpenter’s will mainly consists of gifts, mostly in the form of books, to two groups: rectors and other secular ecclesiasts and past and present city clerks.78 The gifts to ecclesiasts begin with a general bequest of “good or rare” Latin theological books selected from his collection by Reginald Pecock, then master of Whittington college, and William Litchfield, preacher, writer, and rector of All Hallows the Great, to be chained in “the common library at Guildhall, for the profit of the students there, and those discoursing to the common people.”79 Other books go to individuals, specifically to activist secular clergy of the older generation.80 Carpenter’s relative, the future bishop of Worcester, John Carpenter, receives a book on architecture.81 William Byngham, rector of St. John Zachary and founder of a school at Cambridge (later Christ’s College) meant to remedy the “grete scarstee of maistres of Gramer,” receives Roger Dymock’s response to the Lollard “Twelve Conclusions,” with its careful defense of the theology of the almshouse. John Neel, master of the hospital of St. Thomas of Acres in Cheapside, receives one of two copies of the pseudo-Aristotelian Secreta secretorum and Innocent III’s De miseria conditionis humanae: these contrasting but (in a hospital context) equally useful books on bodily and moral regimes, the first remedial, the second ascetic, had been, with “other notable things,” left to Carpenter by his own predecessor at the Guildhall, John Marchaunt.82 Pecock, Litchfield, Carpenter, Byngham, and Neel were all involved in initiatives to establish and staff choir and grammar schools, with a particular eye to raising the level of liturgical training of London’s choristers and lay clerks, many of whom sang in chantry chapels like the one Carpenter endowed at the Guildhall for the salvation of his own soul, with four choristers (“Carpenter’s children”) under a tutor.83 Like many of Carpenter’s labors for the Whittington foundations, especially the almshouse and the chantry chapel at the St. Paul’s charnel, the networks suggested by these names and gifts speak to an interest in the educational and liturgical life of the city: a concern to promote religious orthodoxy, the correct performance of the divine cultus, and the prayerful commemoration of the city’s dead that both parallels and supplements the concern for civic ceremonial displayed in the Liber albus.

The gifts to clerks, which provide a unique glimpse into the reading culture of the educated laymen in charge of London’s legal, financial, and textual resources, go to nine members of the offices of the common clerk and the city chamberlain, households long closely associated with one another. For the most part, these are works of moral philosophy and theology, in some cases written within the genre of the Fürstenspiegel or Mirror for Princes tradition, including several dating from the previous seventy-five years. Two chamberlain clerks, William Chedworth (brother to the bishop of Lincoln and one of Carpenter’s executors) and Robert Langford (Chedworth’s successor),84 respectively receive copies of Julianus Pomerius’s fifth-century De vita contemplativa, on the relationship between teaching, contemplation, and the practice of virtue, and “a book of mine called Speculum morale regium made for a sometime king of France.” This is probably the mirror for princes written for Charles VI in the 1380s by the late fourteenth-century Dominican archbishop of Sens, Robert Gervais, “useful for observing how a king or governor may be excellent and famous and virtuous and glorious and for contemplating the summit of the rule of kingly majesty and its function and reward.”85 Like Alain de Lille’s late twelfth-century Anticlaudianus, left to Carpenter’s former clerk and family friend Richard Mordan, and Christine de Pizan’s Livre du corps de policie, with its vigorous interest in the role of the merchant class in the calamitous politics of early fifteenth-century France, left to another former clerk, Richard Lovell, these texts are in different ways concerned with the place of virtues in the ordered polity and in “imagining the perfect ruler.”86 Accordingly, they suggest in general terms the moral seriousness with which Carpenter and his fellow clerks understood the theological theory of civic authority displayed iconographically on the south porch of the Guildhall, with its positioning of Learning and Law between the cardinal virtues below and Christ above, and the claims for the religious role of city government this iconography implies.

The books given to a third chamberlain’s clerk, Richard Blount, are suggestive in more specific ways, since they include not only more works broadly in the “advice to rulers” tradition—Carpenter’s other Secreta secretorum, bound with Petrus Alfonsi’s exempla collection Disciplina clericalis—and a set of practical civic texts but also a book of ethical writings whose focus is as much on the self as on the civic. Blount is offered lifetime use of “all my books or quartos of the modes of entry and engrossing of the acts and records as well according to the common law of the realm as the custom of the city of London”—a loose gathering of texts like those Carpenter had shaped into the Liber albus—provided these books revert to the “chamber of the Guildhall of London, for the information of the clerks there” after his decease.87 But he is also given outright another book, “my little book De Parabolis Solamonis, Ecclesiasticus, Seneca ad Callionum, De remediis utriusque fortunae, and De quatuor virtutibus cardinalibus”: perhaps a compilation containing glossed copies of two biblical wisdom books, Proverbs and Ecclesiasticus, and a cluster of three closely related works of moral theology or philosophy, two ancient, one modern.88 The ancient works, Martin of Braga’s brief account of the role of the cardinal virtues in the life of the ruler, Formula vitae honestae, and the De remediis fortuitorum bonorum, were widely assumed to be by Seneca. The modern work, by far the longest text in the book, is the De remediis utriusque fortunae: the most widely circulated of the writings of Francis Petrarch, of special interest here for its explicitly theological deployment of the concept of fortune to structure a set of reflections on ethical living in the face of change and death.89

Represented as a response to the pseudo-Senecan De remediis fortuitorum bonorum and its failure to consider remedies for anything other than the “bad face” of fortune, Petrarch’s De remediis was written for the once powerful and still wealthy Azzo da Correggio, deposed lord of Parma and governor of Verona, whose “very circumstances … illustrate abundantly the ups and downs of Fortune,” as well as for the “many strung up on the rack of Fortune, many showered with riches, and many being whirled around on her wheel with great force.”90 The treatise, a long series of brief dialogues between Reason and Joy and Hope on the one hand, Sorrow and Fear on the other, is in two parts, both of which represent the “unpredictable and sudden changes” of human affairs as an “ever present war with Fortuna, in which only virtue can make us victorious.”91 The first, in which Reason counters Joy and Hope’s expressions of pleasure in beauty, long life, wealth, position, health, prestige, political success, and so on with the Stoic reminder that all such worldly goods are passing, focuses intently on the spiritual and existential problems attendant on good fortune. Many have “endured losses, poverty, exile, imprisonment, torture, death, and grave illnesses worse than death,” but Petrarch has “yet to see one who could bear well riches, honors, and power.”92 The second, in which Reason seeks to dissuade Sorrow and Fear from reacting negatively to various misfortunes—from loss of social standing, poverty, and sickness to cramped quarters in which some are forced to live—with variations of the same reminder that lack of worldly goods is in reality lack of nothing, focuses on the myriad ways in which good fortune is subject to natural decline, sudden reversal, and a constant sense of insufficiency.93 As a whole, the work, which we might understand as a humanist extension of the mirror for princes tradition, aims to teach those who are in any number of senses rulers to keep themselves at an emotional remove from the world, arguing that such a steadfast rational and virtuous attitude to fortune is what makes good government possible.

The De remediis culminates in an extended memento mori, which is presented as an antidote to both unreasonable pleasure in prosperity and unreasonable pain in misfortune at once.94 This resolution to the problem of fortune is influenced not only by Stoics such as Seneca and Cicero, who encouraged melete thanatou as a means to detach from the external world, but also by the early writings of Augustine, for whom meditatio mortis is similarly the key to attaining virtue, the reorientation of cognition from self and world toward the true apprehension of God.95 In Petrarch’s treatise, Reason argues that “death calls not for fear but for contemplation,” because only in constant meditation on mortality can humans know themselves as temporal, created beings: “The most harmful of all human ills is to forget about God, yourself, and death. These three are so intimately connected that one can hardly consider them separately.”96 Meditation on death encourages a religiously correct and philosophically dispassionate attitude toward wealth and prosperity, as borrowed, not owned—the status, as we have seen, of merchant wealth in particular, according to Dives and Pauper.97 At death, riches “will return to whence they came, namely, Fortune’s hands. And from there they will pass again and again, from one to the other, and never stay with anyone for long” because “all this time you have had the use of someone else’s goods. Nothing of your own is being taken away from you, but only what you borrowed and are finished using is being called back.”98 In dying, humans join a great mortality community, as “those who stand around your bed, those who you saw before, those you heard of, read about, or could have known, and all those others, either born before or to be born, any place, any time, in the future, they all have taken or shall take this journey.”99 The daily contemplation of death is presented here, at the culmination of the work, as the ultimate means by which to counter both of fortune’s two faces, the good and the bad.