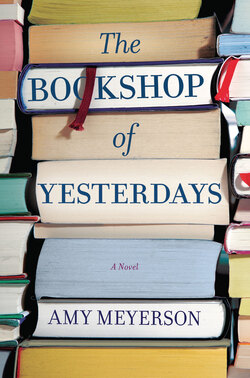

Читать книгу The Bookshop Of Yesterdays - Amy Meyerson - Страница 10

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

The following morning, Mom was already in the kitchen when I wandered downstairs in search of coffee. Blueberry muffins cooled on the island that divided the kitchen from the dining and living rooms. I knew the fridge was also stocked with foods she remembered me liking as a teenager. Cool Whip and strawberries, bologna, chocolate milk—foods, if you could call them that, I hadn’t eaten in years.

“Where are the other twenty guests?”

“Miranda.” Mom dropped her oven mitts and rushed to me. It was only 7:00 a.m., but she was already dressed in black pants and a coral blouse, her curls set to frame her face, her eyes bright with mascara and brown eye shadow.

“I’m so sorry, Mom.” As conflicted of a hugger as Dad was, Mom was the opposite. She always hugged me like if it was up to her she’d never let me go.

“I’m okay,” she said, like she wanted it to be true.

“Is there anything I can do?”

She pointed to the table. “Sit.”

Mom served me a muffin and a cup of coffee like she was my waitress. She sat across from me, watching as I broke the muffin in two. Steam rose from its center.

“It’s good to have you home.” She reached across the table to brush a matted curl from my forehead.

“Thought any more about coming to the funeral with me today?” I asked casually as I picked at my muffin. “It might offer you some closure.”

“I got closure years ago.” She stood and headed to the sink, where she began scrubbing the muffin pan.

I finished eating and brought my empty plate to the sink. I stood beside her in the too-close way she liked. “I worry you might regret it, if you don’t go.”

She turned off the faucet and put her cold, wet hand on my cheek. “How’d I end up with such a sweet daughter?” She returned her attention to the mixer in the sink, “Really, honey, I’m fine.”

* * *

Forrest Lawn was a half hour drive from my parents’ house, so I gave myself forty-five minutes to get there, just in case. My parents loaned me their car and waved goodbye from the driveway.

I rolled down the window before I left. “You’re sure I can’t convince you to come?”

“Miranda, go,” Dad said, too forcefully.

“We’ll see you when you get back,” Mom added.

I watched her as I reversed out of the driveway, waiting for a crack in her facade that would reveal the pain she’d covered with foundation and blush. She shooed me on as though I was dressed up for prom rather than her only brother’s funeral.

When I arrived at Forrest Lawn, the cemetery’s wrought-iron gate looked like it belonged on the east coast, harboring an exclusive country club. Despite leaving early, I was late. Twenty-two minutes late to be exact, late even by LA standards, where everything started ten minutes after it was supposed to on account of the pesky traffic.

“The Silver funeral?” I asked the guard. He pointed up Cathedral Drive toward a hill in the far corner of the property, away from the famous names that lined the more prominently located gravestones.

A crowd of forty people was gathered around the open grave. They were younger, hipper and more diverse than I would have expected, dressed in black jeans and T-shirts, tight dark jersey dresses. I tugged at the collar of my knee-length black dress, feeling acutely conservative and undeniably east coast.

I stood behind the row of people that lined the grave, searching for someone I recognized. I didn’t know whom I expected to be there. My grandparents had died before I was born or old enough to remember them. Mom and Billy didn’t have other siblings. Their uncles had died on the beaches of Normandy and in the Pacific. No cousins or extended family to speak of. No lifelong friends that had been stand-ins for family. Still, I scanned those young faces hoping for someone familiar, perhaps an old girlfriend of Billy’s that I’d forgotten about or Lee the manager or one of the pretty girls who had worked at the café in Prospero Books, now in her forties. Only a few faces looked older than my own. A plump woman in her sixties with plastic-framed glasses and a wiry man with a white goatee and bifocals. The only other person who stood out was a man in a pinstripe suit who, like me, hadn’t gotten the memo on funeral casual.

The crowd shifted as a guy in a hooded sweatshirt and faded black pants walked toward the microphone behind the grave. He swept a mop of hair away from his face, his eyes downcast as he dug into his back pocket to retrieve a sheet of notebook paper.

“This is a Dylan Thomas poem that Billy liked.” He cleared his throat before reading “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” As he read about fighting the dying light, I studied Billy’s tombstone. The dark granite listed his name, Billy Silver, his birth in 1949, his death three days ago. Thomas Jefferson once wrote that the life and soul of history must remain forever unknown. Only the facts—the eternal facts, he called them—were passed down to subsequent generations. These were the external facts of Billy’s life, stripped of any details that made him someone to remember. Why wasn’t he buried with my grandparents in the Westside? Why did he choose to be buried here, between the equally anonymous gravestones of Evelyn Weston and Richard Cullen, in what appeared to be the singles’ corner of Forrest Lawn, wallflowers even in death?

Billy’s friend finished reading the Thomas poem and stared solemnly at the crowd. His gaze circled the rows of people, until it stopped on me. His eyes were clear and so unnaturally blue they caught my breath. They were stunning but cold, making me feel like even more of an interloper than I already did. What was I doing here? I’d told myself I’d come home out of duty and decency and grief. Really, it was because of the card my uncle had sent, the prospect of another one of his scavenger hunts. I didn’t belong here. I didn’t deserve to be beside these sad, beautiful people, commemorating someone I’d practically forgotten.

“You want one?” The girl beside me held a plastic cup in my direction. She was younger than I was, Latina, her sinewy arms covered in ink drawings and Spanish calligraphy. “There’s whiskey or whiskey. I’d recommend the whiskey.” I took the cup and watched as she poured liberally into it.

The older man with the goatee walked behind the microphone, holding his red solo cup toward the crowd. He shut his eyes, and began singing, “Oh Danny Boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling.”

The plump woman in her sixties arrived at the goateed man’s side, and threw a freckled arm around his shoulders, swaying his body with hers as she joined in the old hymn. When they finished singing, the man angled his glass toward the open grave, then the sky, before bringing the cup to his lips.

“‘To the nights we’ll never remember with friends we’ll never forget,’ as Billy used to say,” the girl said, angling her cup toward mine. “You from the neighborhood?”

“What neighborhood?”

“Silver Lake. I haven’t seen you around.”

“No, I’m Billy’s niece.” It sounded like a foreign word—niece—all accented and blunt. Still, I was Billy’s niece. He’d sent me a sign before he died. He’d been thinking of me. We remained something to each other. “How did you know my uncle?” I asked, emboldened by the fact that I was family and these people weren’t.

“I work at Prospero.”

“Prospero Books,” I said longingly. I couldn’t remember the last time I’d said the name aloud and it still hit me with the amazement it had when I was a kid, the sorcery of Prospero, the magic of his books.

The whiskey changed the mood, and everyone started chatting energetically. Laughter carried across the open terrain. The man in the pinstripe suit announced, “If you’d like to continue the reverie, we’ll be convening at Prospero Books.”

“It was nice to meet you.” I waited for her to add, I’ll see you at the store, but she nodded and made her way toward the wild-haired man who had read the Dylan Thomas poem. She whispered to him and they turned to look at me, an inscrutable expression on their faces, or maybe it wasn’t inscrutable; maybe I didn’t want to decipher the hard truth of their stare.

I sipped my whiskey even after there was nothing left in the cup, watching everyone walk toward the mass of cars collected on the side of the road.

“You wouldn’t happen to be Miranda?” The man in the pinstripe suit approached me, his hand extended. He was older than he’d appeared at a distance, his sandy hair lightened with peroxide in place of youth. “I was hoping to see you here. I’m Elijah Greenberg, Billy’s lawyer.”

I was about to ask him how he knew I’d be here. Billy must have told him about me. He must have known about The Tempest, the quest that lay ahead.

“I’m so sorry about Billy.” He escorted me toward the two cars left on the side of the road. “Are you coming to the celebration?”

“The celebration?”

“Of Billy’s life. Strange way to put it, I know. That’s how Billy wanted it. ‘I don’t want any of this sad business,’” he said in a deep voice that I assumed was supposed to be Billy’s. “‘That shouldn’t be your last memory of me.’”

I wanted to go, but I could still hear the girl’s tone as she’d said, “Nice to meet you,” like she wouldn’t be meeting me again. I could picture her facial expression, and that of the big-haired man as they regarded me from afar, the absentee family arriving too late. I couldn’t stand the thought of their continued disapproval, no matter how much I wanted to go to Prospero Books.

“My parents are expecting me home,” I said.

“Why don’t you come by my office tomorrow?” He handed me his card. “There’s the matter of the will to discuss.”

“The will?”

“Your inheritance.”

“My inheritance?”

Elijah unlocked his car and opened the driver side door. “How’s ten tomorrow morning?”

I nodded, speechless. Curiosity spread through me like a fever. Delirium. Euphoria. The feeling of Billy. My instincts were right. First Billy called me home with the card, The Tempest. Now, the next clue was waiting for me in Elijah Greenberg’s office, in the form of my inheritance.

* * *

By the time I found my way back to the I-5, it was after seven on the east coast. Jay was either home, resting up for another early morning of soccer camp, or at the bar around the corner from our apartment, drinking off eight hours of cocky teenage boys. I decided to take my chances.

“Hey, babe,” he answered on the fourth ring. Jay had never called me babe. Sometimes he called me M or Mimi after he heard Dad’s nickname for me. Never babe or hon or dear, endearments manufactured for the masses.

“Hey yourself,” I said.

“I just finished cleaning the kitchen. It will still be to your standards when you return.” The apartment had taken on new levels of cleanliness when I’d moved in. OCD clean, Jay called it, a habit drilled into me by Mom, who believed company-ready should be the natural state of any household.

Jay sighed as he flopped audibly onto the couch. I heard the television turn on, and bit my tongue before starting in on that fight again. Jay did everything with the television set to soccer, or when there wasn’t a match, to football, baseball, basketball, even hockey if he was so desperate. The only time he didn’t have sports on was when we were having sex.

“This a bad time?” I asked coldly.

If Jay intuited that I was annoyed, he decided to play dumb. The television blared in all its glory. “Trevor was out sick today, so I was on my own. Who gets sick on their second day of work? I want to get him a job as my assistant coach. With this bullshit, no way the school’s going to hire him.”

I didn’t want to talk about Jay’s friend Trevor.

“As long as you keep putting out a winning team, they’ll do what you want to make you happy.” I slowed down again when I reached downtown, about a half mile from the entrance to the 10. I shouldn’t have called. Jay was in his I-want-to-chill-at-the-end-of-a-long-day mode, which barely included me when I was home and not at all when I was a phone call away. It was something we were working on, breaking him of his single habits and me of mine, although most of mine were stored in a warehouse somewhere in South Philadelphia.

“Sorry, I’m being a jackass. The funeral was today, right?”

“Just coming from it. I didn’t know anyone there.”

“Did you expect to?”

“No. It still upset me that I didn’t.”

“Well, there’s no reason why you would have known anyone. That shouldn’t make you upset,” he said. Soccer fans screamed through the car’s Bluetooth.

“Turns out I was right, though. My uncle left me something in his will.”

“So I guess this means you won’t be coming home tomorrow?”

“Who said I was coming home tomorrow?” I shook the steering wheel as though it might make traffic move, but I was trapped on the freeway, hostage to our conversation.

“I figured after the funeral you’d come home.”

“Didn’t you tell me not to rush back?”

“Was that me?”

“I believe your exact words were ‘take the time you need.’”

“For which you called me a sentimentalist,” he retorted.

“Touché,” I said, and Jay laughed. “A few more days. Billy’s lawyer will give me the next clue. I’ll figure out what Billy wants to tell me about him and Mom, and I’ll be home before you can even miss me.”

“I already miss you.”

“Well, then, before you can go back on your word to keep the apartment in tiptop shape. The end of the week at the latest,” I promised.

* * *

Mom insisted on going with me to meet Elijah.

“I can go alone,” I said as she handed me a French omelet. I’d told her that Billy had left me something in his will, not that he’d already given me a clue, nor about the hunt that lay ahead. “If it’s going to be difficult for you, I’m happy to go on my own.”

“I’m coming with you,” she said. “End of discussion.”

She took off her apron and disappeared upstairs to get ready. I watched her go, feeling like a teenager about to get caught for going to a party or getting a clandestine tattoo. Jay was right. I should have told Mom about the clue before I came home, before Billy became something I kept from her.

Elijah worked on Larchmont, so Mom and I sat in I-10 traffic, crawling our way east. I watched her eyes shift between the rearview and side mirrors to the congested road ahead. She rubbed her cheek the way she did during suspenseful scenes in movies.

“Miranda, please stop staring at me like that. Really, I’m okay.”

I continued to watch her more furtively, sneaking sideways glances that she likely saw. Despite her best efforts, she wasn’t okay. I didn’t understand why she wanted to hide her feelings. I braved a lingering look at her and thought, not for the first time, that I didn’t really understand my mother at all.

Mom exited the highway and headed north on La Brea past furniture stores and lighting warehouses.

“The funeral was pretty weird yesterday,” I said, realizing she hadn’t asked me about it.

“Billy always was a bit eccentric,” she said distractedly.

“I keep remembering things about him.” I circled my way toward the conversation I wanted to have with her. I needed to tell her about The Tempest before we got to Elijah’s office and he did the job for me. “Remember the time he built a simulator in our backyard to teach me about hurricanes? Or when he set up the sprinklers to create a rainbow?”

“He was always good with you,” she said almost forlornly, almost like she missed him.

“We were so close, then we just stopped seeing him.”

“We were close.” Mom paused to collect her thoughts. The massive storefronts narrowed to boutiques, cafés and frozen yogurt shops. When she stopped at a light, she added, “But Billy was unreliable. He was always running off. I wouldn’t know if he was alive or dead, if he was coming to dinner, if he’d left the country. I was worried all the time. It got to be too much.”

“What does that mean, ‘it got to be too much?’”

Mom leaned over me to read the names of the streets that ran perpendicular to Larchmont. “Keep an eye out for Rosewood.”

I wanted to tell Mom that she couldn’t weasel her way out of the conversation that easily, to remind her of Prospero’s words—You must now know farther—to let her know that Billy was intent on revealing the past to me, and I wanted to hear it from her first. Mom never responded to anything that smelled remotely of a threat. If she didn’t want to talk to me about what had torn them apart, nothing I could say would change her mind, not even if I told her that Billy had planned something for me.

A few blocks later, we found Rosewood and parked outside the law offices of Elijah Greenberg. June Gloom sat heavy in the sky, dreary and somber. Throughout June in Los Angeles, the morning’s haze promised an overcast day, but without fail, it burned off, and when the afternoon became sunny, it was all the more spectacular for the bleak morning. Today, however, as I studied the sky, I didn’t see a hint of a beautiful day to come.

Elijah guided us into his office where we sat in firm leather chairs as we waited for him to find the right file among a large pile of files on his desk. Mom absentmindedly tapped her foot, shaking her leg so violently I could feel the vibration in the seat beside her. I put my hand on her knee to calm her. She flinched, turning to me with an expression of fright I hadn’t expected.

Elijah opened a folder in slow, deliberate motion. “As you know, Billy was the sole proprietor of Prospero Books.” This caught my attention. I edged forward, curious to see where this was headed. Elijah cleared his throat and read from Billy’s will. “‘I, Billy Silver, hereby bequeath my property, 4001 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, California, subject to any mortgages or encumbrances thereon, to Miranda Brooks.’” Elijah handed me a set of keys. “The property includes the bookstore and an apartment on the second floor. I’ve had it prepared for you.”

The keys were cold and smooth, their notches worn from use. I’d expected a map or one of Billy’s riddles, but the keys to Prospero Books? I was a middle-school history teacher. I didn’t know anything about running a business, let alone a business as specialized and important as a bookstore. But I couldn’t focus on those pragmatic concerns. Prospero Books. I could still remember its sweet and musty smell, its feeling of springtime throughout the year. After all these years, I would get to return to that smell, that feeling, again.

I looked over at Mom, sitting erect beside me, alert as prey being stalked. Her eyes darted across the will, reading it upside down. She was so still that if I touched her she might have shattered into a thousand pieces.

“Mom?”

She shook her head. “It’s okay. Let’s keep going.”

Elijah closed the file and opened the desk drawer beneath his computer. “In addition to the store, he also asked me to give you this.” He handed me a copy of Jane Eyre.

The cover depicted Jane’s silhouette, her profile dark against the beige background. I ran my finger along the contour of her face. I’d read the novel in high school, again in college, had logged the love between Jane and Mr. Rochester as one of literature’s best, even if Mr. Rochester was by all modern accounts a bit of a creep. If it had been one of the Boxcar Children books, a copy of The Westing Game, it would have reminded me of the afternoons I’d spent in Prospero Books drinking hot cocoa from an oversize mug as Billy read over my shoulder, together trying to reason the clues Mr. Westing left for the tenants of Sunset Towers. But Jane Eyre? I’d never read it with Billy. I had no idea why he would have left it for me now.

I angled the book toward Mom, and she leaned over to see the title. Her face remained stoic. I couldn’t tell if the title meant anything to her, either.

The novel’s spine was split in several places, and the middle bulged awkwardly where an antique key was nestled between the pages. On the page behind the key, a few sentences were highlighted.

One does not jump, and spring, and shout hurrah! at hearing one has got a fortune; one begins to consider responsibilities, and to ponder business; on a base of steady satisfaction rise certain grave cares, and we contain ourselves, and brood over our bliss with a solemn brow.

Did Billy know I would feel bliss, that I would rush into excitement? Fortune. Responsibilities. Grave cares. A solemn brow. Was he reminding me that my new fortune arrived because of his death? I skimmed the text around the highlighted section and remembered: Jane did not jump and spring and shout hurrah! at hearing she’d inherited a fortune from her uncle, John Eyre. Her uncle! Her father’s brother whom Jane didn’t know. Instead, Jane expressed her dismay that she couldn’t have a fortune without her uncle’s death, that she’d dreamed of connecting with him and now never would. But Jane’s uncle had searched for her. He’d been unable to locate her before he died. Billy hadn’t gone looking for me until he was already dead. If he had, in the modern age of the internet and Facebook, he would have found me easily. If he’d thought of me, why hadn’t he come looking? Why did he wait until we no longer had a chance to reconnect?

“Is that it?” Mom asked Elijah with the impatience of a student I’d held after class.

“Well, there are several details about the store to discuss. If you’re in a rush, Miranda and I can set up another meeting.”

“That would be great.” Mom motioned me out.

“I’ll call you,” I told Elijah. As I stood, the cover of Jane Eyre fluttered open. I noticed something written inside the front cover. Cursive writing, nearly faded: Evelyn Weston. I could picture that name in all caps, carved into the gravestone beside Billy’s. So, Billy hadn’t been buried alone, after all. But who was Evelyn Weston?

* * *

On the I-10 West, Mom drove in the far left lane five miles below the speed limit. Cars passed us on the right, drivers honking their horns and raising their fists as they raced past.

“You want me to drive?” I asked, knowing she wouldn’t let me.

“I’m fine.” She slammed the gas pedal, and the car lurched forward with nervous energy.

“I can’t believe Billy left me his bookstore.”

“It’s inexcusable,” Mom said as she pulled onto the ramp for the Bundy Drive exit. “Putting that kind of burden on you.”

“It’s not a burden. I loved Prospero Books.”

“Loving something and being responsible for it are two very different things.” She gripped the wheel so forcefully her knuckles turned white.

“Why do you think he left me a copy of Jane Eyre?”

“I have no idea.” The gift seemed to anger her regardless of whether she knew what it meant.

“Was it an important book to Billy?”

“I just told you I have no idea.” Mom turned on the radio to a top forties station, a type of music I knew she didn’t like. We listened to syrupy vocals and catchy rhythms until Mom pulled into the driveway of our Spanish Revival. “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to snap at you,” she said as she stopped the car. “I don’t think Billy considered how much this would hurt me.”

I twisted the antique key I’d found in Jane Eyre between my fingers. It was oxidized almost completely black. It had to open an old safe or jewelry box tucked away in the other part of my inheritance, Prospero Books. And it had to have something to do with the name left in cursive font in the front of the novel.

“Do you know who Evelyn Weston is?”

Mom jolted. “Where’d you hear that name?”

“At Forrest Lawn. Billy was buried next to her.”

“You saw Evelyn’s grave?” Mom appeared nervous, suddenly frantic.

“Was she Billy’s wife?” It was the only logical reason he would have been buried beside her.

“She was,” Mom whispered as she stared at our familiar white house. The lines around her eyes were more pronounced than they’d been last time I’d seen her. Everyone said I looked like Mom. We had the same curly hair, same narrow builds. Her face was longer and narrower than mine; her speckled brown eyes were more golden than mine had ever been. I’d never be as pretty as Mom.

“Was she someone he met after us?”

Mom turned toward me, confused. “You said you saw her grave?”

“I didn’t look at it very closely. I don’t remember anyone ever mentioning her.”

“He was married to her before you were born. She died a long time ago.”

“And Billy never remarried? He never had a family?”

“He only ever wanted Evelyn.”

“Why’d he name the bookstore Prospero Books? Did it have anything to do with me?” As a child, I thought Prospero Books was named for me, an homage to my namesake, like Prospero Books lived and breathed with me, like when I wasn’t there, it ceased to exist.

“It was open before you were born.” Her tone remained even.

“Did you name me after the bookstore?”

“I named you after Shakespeare.”

“You and Billy just happened to pick the same play?”

“It was Evelyn’s favorite play.” She smiled, shrugging off her sadness. “How much of a disaster do you think the kitchen’s going to be after your father has had free rein of it all afternoon?” Mom patted my leg and stepped out of the car into the bright afternoon.

I watched her navigate the pathway to the front door, piecing together the details I’d just learned. Billy had a wife before I was born. Her name was Evelyn Weston. She loved The Tempest. I was named for Shakespeare’s Miranda and for Evelyn’s. Evelyn Weston must have also loved Jane Eyre. Mom had to know this. Even without seeing Evelyn’s name in the novel, Mom had to know why Billy left it to me. I didn’t know how it hadn’t occurred to me before. Mom was keeping a secret.

* * *

“Don’t expect your mother’s cooking,” Dad warned as he put the eggplant parmesan into the oven. “Will you let her know dinner’s almost ready?”

I found Mom outside, holding a pair of shears as she decided which flowers to cut for the table. Behind her, the sky was ignited a rich orange lined in pink. I couldn’t see the setting sun, but it left its legacy across the sky.

“Tonight’s an amaranth night,” Mom said, watching the sky. “Amaranth’s not right.”

“It’s carmine. And cerise,” I said. Being raised by Mom, I could name more colors than most people knew existed. That was my skill as the daughter of a decorator, but I didn’t want to talk about shades of pink, the glorious hues of Southern California sunsets. “Dad says dinner’s close.” I snuck a final glance at her, trying to remember when she’d become that way, hesitating before she responded in conversation, when she’d fallen into the habit of covering her mouth as she laughed, when she’d replaced her red nail polish with nude, her crimson lipstick with vitamin E stick. She still listened to Jefferson Airplane and Fleetwood Mac, still meditated for ten minutes each morning, but at some point, everything she owned had faded to muted shades of pink.

When my parents met, they were both living in New York in lives they’d retired before I was born. Mom was twenty with ironed hair and bright miniskirts. She was the lead singer of the Lady Loves, an all-girl band that had a residency at a club in the East Village where Dad represented the owner. When the owner had introduced them, Mom had looked at Dad’s extended hand like it was covered in mud. He’d followed her eyes down his suit and tie to his loafers.

I enjoyed your set, Dad said, putting his hand away.

You like rock? she said with the disdain only a twenty-year-old could muster.

Jesus, Suzy. The guy’s trying to give you a compliment. Cut him some slack for fuck’s sake, the owner said.

Fuck you, Harry. Mom grabbed one of the amps and stormed offstage.

Don’t let her get to you, the owner said to Dad. Suzy thinks ’cause she’s a musician she has to act like an asshole every now and again.

From the first time Mom spoke to Dad, that was it. He went to see the Lady Loves every Friday night. He liked to watch Mom sing, waiting for the moment when she forgot she was onstage, forgot her tough facade, and her face softened as the sweetness of her voice consumed her. It happened during every performance. In that moment, he saw that she was still young, that she hadn’t yet been hardened by life.

There was nothing noteworthy about the night Mom sat at his table. After she finished her set, she pulled up a chair and tied her hair away from her face. Her features were small and girlish. She didn’t smile, but Dad could tell she wanted to.

How many ties do you own? she asked Dad.

The question startled him, and he adjusted the knot on his wool tie. He owned so many ties he rarely wore the same tie twice. No one had ever asked Dad about his collection. As far as he could tell, no one had ever noticed.

About two hundred, he admitted.

Why would anyone need two hundred ties?

They wouldn’t.

So why do you own so many?

Dad didn’t know how to explain it to her. His parents and younger brother had died when he was in college. His uncles had been killed in the war before he was born. His grandparents were long gone. He had childhood friends, law school buddies, others at the firm, a steady stream of girlfriends, but no one he could count on to give him a birthday present each year, to make plans every Thanksgiving. So Dad bought himself ties for Christmases and promotions, a reminder that he could look after himself.

It would be weirder if I owned two hundred pairs of shoes, he said.

Mom giggled and ran off to help her band pack up. From the first time Dad made her laugh, that was it for Mom, too.

* * *

When I went back inside, Dad was sitting at the dining room table, trying to fold linen napkins into Mom’s perfect origami.

“Here,” I said, taking them from his hands. I showed him how to fold it into three long strips, to tuck one side up and then the other into a perfect envelope.

“You make it look so easy,” he said, and disappeared behind the island into the kitchen.

Dad rummaged around the cabinets, banging pans as he put them away. I took out my phone and typed “Evelyn Weston,” stopping when I couldn’t think of anything else to add to my search. Several Evelyn Westons popped up with LinkedIn, Twitter and current IMDB pages. The Evelyn Weston I was looking for had died long ago, in an era before social media and the twenty-four-hour news cycle. I’d have to find out about her the old-fashioned way, by talking to people instead of devices.

Dad returned with two wooden candleholders. The candles sat crookedly in the bases.

“Turns out I’m not a whittler.” When Dad retired, he’d needed a hobby. He’d never been particularly handy. Anything more complicated than changing a light bulb had required the aid of a handyman. Now, suddenly in his mid-sixties, Dad was determined to become a craftsman. Mom had suggested he take a class, but Dad insisted that part of being a craftsman was being self-taught, so he bought books and magazines, watched YouTube videos. He started with a rocking chair, then quickly downgraded to a box. “Did I show you the bookshelf I made? I’m staining it now. If you didn’t know, you might actually think someone had paid for it.”

“Did you know Billy’s wife, Evelyn?” I asked more abruptly than I’d intended.

“Your mom told you about Evelyn?” He sounded surprised without being alarmed. Then again, Dad was good at containing his emotions. He’d had practice for years as a lawyer.

“She said she named me after Evelyn, after her love of The Tempest.” I fudged it a little. If Dad thought Mom told me more than she had, he might tell me more, too. “Were she and Mom close?”

Dad reached for the candleholder, worrying the wood with the pad of his thumb. “Since they were in kindergarten.”

“They grew up together?” Dad nodded, his attention still focused on the unstable candleholder. “How’d she die?”

He peered over at me. “Why are you asking?”

“I didn’t know Billy was married. I’d never even heard the name Evelyn before today. Do you know how she died?”

“Evelyn had a massive seizure.”

“Was she epileptic?”

“I don’t think so.” Dad looked through the French doors toward Mom in the garden, inspecting the soil beneath her rosebushes. “Why don’t you go see what’s taking your mom so long.”

“She said she’d be in in a minute. What was wrong with Evelyn?”

The oven timer went off, and Dad sprung at its chime. Of course he wasn’t going to tell me about Evelyn. He and Mom were a unit, inextricably close, and sometimes it had made me jealous how coupled they were. Of course, if Mom had a secret, Dad did, too.