Читать книгу Traveling with Sugar - Amy Moran-Thomas - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

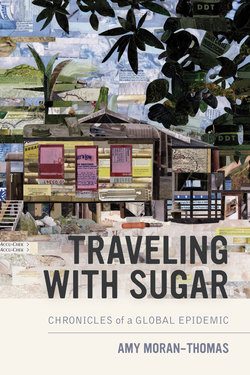

ОглавлениеApproach

Emergency in Slow Motion

Sugar . . . has been one of the massive demographic forces in world history.

—Sidney Mintz, Sweetness and Power

A lot of people, countrywide, in the whole entire world, here in Belize and Dangriga, are traveling with sugar.

Diabetic is a dangerous thing . . . It’s like cancer . . . It makes you get weak, it makes you get blind, because of the sugar in your eyes and the pressure . . . It makes you get slim, especially if you don’t know . . .

That is the most [serious] thing that is hampering the whole entire world. The diabetic sugar . . .

The whole of your family can get the diabetic. You have to look out [even] if you don’t catch it—maybe your children later on to come . . .

—Anne, expanding on living with diabetic sugar in Belize

I have never seen a good stand-alone picture of “diabetes.” If not for Mr. P’s storytelling, I might never have glimpsed it at all. He was paging through a family album on the kitchen table in his home on Belize’s south coast, showing me pictures of his wife. He smiled back at the old photos of her as a Garifuna teacher standing firm beside a rural schoolhouse. We watched as on the pages she became a mother, then a grandmother. The next time Mrs. P appeared in the album, she was suddenly on crutches. “Sugar,” Mr. P said simply as he paged forward in time, the photographs sharpening in color and filling with grandchildren. In a family Christmas picture his wife’s entire right foot was missing. At one wedding, both of Mrs. P’s legs were gone below the knee. We watched her disappear a piece at a time from the pictures, until she was absent altogether.

Later, that scene kept looping in my memory: Mr. P turning the album’s pages carefully so as not to crinkle its plastic sleeves, the photographic record of loss a surreal counterpoint to the stories he told about raising a family and caring for the generations to come. About the harrowing parts, he only ever repeated, “Sugar.” Back then, I didn’t know about the dozens of different cellular pathways and blood capillary injuries by which you can lose a limb to diabetic sugar’s wears. But I could never forget how he narrated a series of slow losses that somehow had come to feel inevitable.

At the time, I thought I would be writing about another health topic altogether. Early in graduate school, I went for a preliminary visit to Belize to lay foundations for what I thought would become an anthropology project about people’s perspectives on worm control programs. Mr. P had obligingly shown me the apazote leaves in his garden, which could be added to a pot of stew beans for worm treatment. But clearly, intestinal parasites seemed a minor footnote to him, in contrast to the pink housedress still floating on a hanger near their kitchen window. The more people I talked with, the more it appeared that the pressing health issue on many people’s minds was not parasites, but rather the shape-shifting disease of diabetes.

The worms I had initially planned to write about are so easy to visualize. Public health campaigns focused on parasites often put cartoons of their targets on T-shirts and sponsor museum exhibits that display worms in glass bottles of formaldehyde. Fascinated viewers frequently do not read the captions; they just stare at the grotesque-looking specimens. Diabetes, in contrast, is strangely ineffable. You can’t show it to anyone in a jar. It has no totem: no insect vector to put on letterhead like malaria-bearing mosquitoes, no virus to blow up under a microscope and target like Ebola, no tumor to visualize fighting like cancer, no clot to bust like a stroke. It eludes any single, self-evident image.

As Mr. P showed me, in order for most pictures of diabetic sugar to mean much at all, you need to know something about their before and after in time and place. Yet traces of diabetes were everywhere in Belize, once people taught me to pay attention to the quiet, constant presences that so many lived with. I began to glimpse the negative spaces of what was missing: Bodies that sometimes slowly stopped healing. Potent medicines and devices that sometimes slowly stopped working. Specters of lifesaving technologies that existed somewhere else in the world. Memories of former vegetable gardens and lost homelands. Loved ones changing in photograph albums. Missing limbs, failing organs. An empty dress left hanging to outline an absence.

I didn’t know how to read those signs when I first walked Belize’s southern coast, observing what washed up along the tideline. But like my interviews about the health of people and places, the tide arriving from the deep ocean presented a knot of entwined lives I didn’t know how to untangle: the last nylon strings of “ghost nets” that now make up half of the ocean’s plastic debris, long abandoned by fishermen but still catching life until they unravel; curds of broken Styrofoam in clotted algae; hunks of dying coral from the heat-bleached reef; thin gleaming strips of brown seaweed that looked as if they’d been unspooled from the reels of an old cassette tape. Odds were that most of the bright microplastic shards had once been food containers, perhaps ejected from passing cruise ships decades ago in order to be worn down to such confetti-sized slivers. I watched as local women deftly swept the day’s debris from their stretch of beach, treating the sand underfoot like the floor of a well-tended kitchen.

SHORELINES

These are some of the shorelines of sugar to which the stories ahead will keep returning.1 On a nearby wooden porch worn gray by brooms and sand, I used to sit sometimes with Cresencia and her Aunt Dee in the afternoon when it was too hot to walk anywhere. They would laugh about how I looked even whiter when sweating out beads of sunblock and invite me to stretch with them along the steps, trying to catch a little breeze from the sea. Dee liked to show me the latest foil punch card of tablets from her small bucket of “sugar pills”—an old joke that stayed funny both because they were pills for her sugar, and because she honestly could never tell whether the clinic’s diabetes medications were working better than a placebo. Cresencia had stopped taking insulin injections for carefully weighed reasons after the hospital had last given her up for dead. But from the porch, you could see the tree where a meal of lavish Garifuna dishes had once been buried in the sand as part of an emergency chugú, offerings for the ancestral spirits who had revived her from what her physicians were certain would be an irreversible coma.

Not far from there, on a sunny overgrown highway parallel to the coast, a teenager with type 1 diabetes named Jordan used to walk in a determined half delirium, trying to reach the hospital before diabetic ketoacidosis set in. It was also along this coastline that a legendary healer with diabetes named Arreini used to send me with a tub to hang her sopping laundry after we finished at the washboard, little chores that were part of the daily test and price of being an old midwife’s student. If I didn’t use enough extra clothespins for her heaviest shirts to stay on the line in the stiff sea wind, she would snap at me, “Merigan!” (American), and I was not allowed to ask her any more questions for the night.

Somewhere far across this water lay the sugar islands from which her ancestors had come, and toward which this story will slowly wend back in trying to understand the sugar now rising in her family’s bodies. It was also in Arreini’s seaside kitchen where I met her daughter Guillerma when she was hoping to receive dialysis to clean her blood—even though such intricate technologies from abroad were nearly impossible to procure at that time, much less maintain. Some of these friends have thrived for many years past medical predictions. Other people I knew dealt with limbs that eroded from diabetic sugar and eventually required amputation. Many of their heaviest losses happened between my irregular trips back, although over the past decade I have also known many people whose injuries were painstakingly mended.

Most everyone in Belize had somehow witnessed the long list of strange ravages caused by diabetes: blindness, renal failure, bone disease, deadened nerves and numb limbs, pain shooting through limbs or stinging like needles, hunger that did not stop when you ate, thirst that lasted no matter how much water you drank. Whenever I thought I finally knew what diabetic injuries looked like, it seemed I would encounter some new manifestation. Like a dream or a nightmare that kept revealing more images. Once, a friend called me to come over after midnight, but there was nothing either of us could do. We stood watching her mother, Sulma, running through the house as it got harder to catch her breath or even breathe, after years of diabetes complications had contributed to organ failure. Her children had saved up to buy her an oxygen tank, but it cost one hundred dollars and had already run out. Sulma thrashed through the kitchen like someone trying to claw toward the surface, only there was no water. It looked like someone drowning in the open air.

“Far from being a disease of higher income nations, diabetes is very much a disease associated with poverty,” Jean Claude Mbanya of Cameroon has argued, writing as president of the International Diabetes Federation. “The global community still has not fully appreciated the urgent need to increase funding for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), to make essential NCD medicines available for all and to include the treatment of diabetes and other NCDs into strengthened primary healthcare systems. The evidence for the need to act will soon be overwhelming.”2

The president of the Belize Diabetes Association, Anthony Castillo, once told me how strangers often tell him he doesn’t look like he has diabetes. He laughed about this: “Well, how are you supposed to look? Is there a look?” And it’s true that if you went by the pictures that tend to show up in international papers, it would be easy to mistake globally rising diabetes for a well-understood, generally mild affliction simply linked to excess. When international media coverage of diabetes appears at all, it often implies individual misbehavior—as if people with diabetes simply cause their own conditions—like the upsettingly typical Economist headline “Eating Themselves to Death.”3

These commonplace news stories and assumptions probably would not upset me so much now, if I had not once accepted some version of them myself.

A GLOBAL EPIDEMIC AS SEEN FROM BELIZE

Although it took me awhile to realize, I was one in a long line of outsiders who traveled to places like Belize assuming that infectious diseases must be the country’s key health issues. Contagious conditions could be serious matters too—the Stann Creek District, where most of this book is anchored, was experiencing one of the highest HIV/AIDS rates in Belize, and Belize had the highest rate in Central America.4 Yet as Garifuna anthropologist Joseph Palacio observed of HIV/AIDS in Belize: “It is a disease that is killing our people. But there are other diseases that are not receiving as much attention. They are diabetes, hypertension, and glaucoma. There is hardly one of us over 40 years of age, who does not have one or more of these public health problems.”5

During my initial visit to Dangriga, I asked a prominent Garifuna physician for feedback on my proposed project. He urged me to focus on diabetes and its many chronic complications instead of parasitic worms. He also offered to mentor the project if I came back to spend a year in Belize, getting to know people who were interested in being interviewed about their experiences and trying to learn something about the ways they were making sense of what was happening.

Many doctors worldwide are also confused by the ways diabetes is now changing. Type 1 (about 5 percent of the world’s cases) used to be commonly called “juvenile diabetes,” while more gradually developing type 2 was labeled “adult onset diabetes” (about 95 percent of cases). They are both rising steeply. Over one million children and teenagers worldwide are now estimated to have type 1 alone.6 But today, more children are also developing type 2, and more adults type 1. In untreated versions of either type, high or low blood sugar wears on the blood vessels carrying it. These vascular complications can accrue into severe injuries over time, including organ damage and limbs with circulation so limited that even tiny ulcers might end in amputation. Some researchers today propose to frame types of diabetes instead more like gradations on a spectrum, offering new labels: severe autoimmune diabetes; severe insulin-deficient diabetes; severe insulin-resistant diabetes; mild obesity-related diabetes; and mild age-related diabetes.7 Many of the first people I met in Belize, though, simply called it all sugar. I framed this project’s scope accordingly.

By the time I returned to live for a year in southern Belize in 2009–10, I had read everything I could find about diabetes. There was an odd dissonance between the tenor of U.S. public health conversations at the time, where the topic was still often assumed to be minor background noise, and statistics I could not really fathom. For instance, the International Diabetes Federation estimated that diabetes annually killed more people worldwide than HIV/AIDS and breast cancer combined.8 Somehow, I typed abstract numbers over and over into research proposals back then without grasping the implication that a significant number of the people I was getting to know were going to face untimely deaths.

This book is set in Belize, but it also signals a global story. Diabetes takes specific shape in each life, family, and nation—but it’s also spreading and causing unevenly patterned injuries and deaths in nearly all countries in the world today. Belize was dealing with the situation about as well as a very small country with limited resources initially could manage. Most health workers and policy makers I encountered in Belize cared greatly about trying to address the rising issue of diabetes. The uneasy scenes in this book show just how complicated a global problem diabetes is—even for a small country labeled “middle income” by the World Bank’s relative standards, where so many community leaders and caregivers are working hard to respond. Many health officials and doctors in Belize actively encouraged critical dialogue, and were trying to expand discussions about the next steps against a growing epidemic in which their offices and many others have some role to play in future policies. But the fact is that the food systems and agricultural toxicities contributing to diabetes are domains far beyond the purview of any Ministry of Health alone. Even the wealthiest governments in the world have not managed to bring diabetes under control.

National headline, August 2010.

Belize is so beautiful that its reputation as a vacation spot for Europeans and North Americans can saturate even academic visions and distract from serious life struggles. The country’s name often brings cruise ship brochures to mind. But many citizens, of course, also struggle with material constraints and social issues similar to those in neighboring countries, as much careful anthropology in Belize has shown.9 Still, I have received enough questions over the years from audiences who have not taken social struggles in Belize seriously that it is worth reprising a thumbnail sketch of resource context: Belize is somewhere toward the lower economic range of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. It is among the countries where the average income is more than four thousand dollars but less than five thousand dollars, according to World Bank estimates of GDP per capita in 2016. For a sense of regional reference, the other five countries listed in that income range include Jamaica, Guyana, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Paraguay.10

The Stann Creek District has the highest rate of diabetes in the country, nearly double the national average.11 I talked with all kinds of people across Belize’s tiny and diverse population. But as I began to be introduced to families dealing with diabetes, I ended up meeting a disproportionate number of Garifuna people (more properly, in plural, Garinagu). Both Black and Indigenous,12 Garinagu make up some 5 percent of Belize’s overall population but represent the majority of residents in Dangriga. They number among the world’s surviving speakers of a Carib-Arawak Kalinago language and widely consider themselves a “nation across borders,” as Joseph Palacio puts it,13 with thriving communities across Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, Nicaragua, and U.S. cities from New York and Los Angeles to Chicago. “Certain diseases are known to have high incidence among the Garinagu relative to the wider population,” the National Garifuna Council (NGC) of Belize wrote in its statement on health. “These include diabetes, hypertension, hepatitis, cataracts, and glaucoma. There is urgent need for studies to be carried out as well as the provision of treatment.”14

Wading with patients across washed-out roads knee deep in mud to keep doctor’s appointments, or traveling by canoe alongside everyone else when Tropical Storm Arthur washed out Kendall Bridge (which cut off the single road that linked southern Belize to the rest of the country and its only tertiary care hospital), I saw how realities often labeled “environmental” in the keywords of an academic journal were already part of the terrain that people with diabetes were negotiating in life. Nurse Suzanne recalled floating from rooftop to rooftop a few days after Hurricane Iris to deliver diabetic pills and insulin. The rough boat ride through floodwaters made her seasick, but she had heard how many families—on nearly every rooftop—had at least one person going into a coma or other diabetic emergency on top of their houses.

Once, I rode through the Maya Mountains in the back of a slow-moving ambulance with Paulo and his young daughter Elisa, wondering about tipping points. Elisa’s pharmaceutically induced high blood sugar was a secondary concern to the fact that her skin was “coming unglued,” which may also have been a side effect of the steroid medicines. We never knew for sure. There was no IV rack, so Paulo and I took turns holding the bag until our arms shook. None of us had been inside an ambulance before. We had imagined speeding to Belize City, but instead we told each other jokes about wishing bus drivers would travel this slowly along the precipitous highway.

Years later I followed behind Paulo as he chopped dense jungle plants away to clear Elisa’s grave, the surrounding vegetation’s growth a ruthless account of the years I had been gone. I have never felt more responsibility than when I learned that her mother, Angeline, had waited three years for me, and together we made the trip to see her daughter’s grave for the first time. Afterward, Angeline handed me a photo of herself kneeling with open arms as Elisa took her first baby steps. The fact that the picture’s chemical exposures had outlasted Elisa’s seemed to dissolve all the words we tried to say. I gave them an image in return, an ornament engraved at a Pennsylvania Christmas shop. They cut the ribbon off and nailed it to the dash of their pickup truck.

Elisa’s real name is written on that ornament, but not in this book. One difficult decision in finalizing this project was that most of its contributors requested that I use their actual names. “But then it wouldn’t be true,” one research contributor protested, when I asked for her input choosing a pseudonym. Others did prefer to create new names, as Belize is such a small place.15 For this reason, I have mostly stuck with typical anthropological conventions of changing people’s names unless they are public figures whose names have been previously published, changing place names except for district capitals, and at times blurring particular identifying details. Still I remain uneasy about these trade-offs, wanting to recognize people’s intellectual contributions to this project.

On the other hand, most everyone I met in Belize has more than one name. When Antonia later told me to call her Beh, she said that when I first arrived at her door with a nurse asking for her by her legal name, she knew we had not been sent by friends. Her neighbor Kara had not even known her own legal name until she went to vote for the first time and discovered that in the state’s eyes her name was Roseanne. Her mother had chosen to call her children by one set of names in real life and to write another name on official documents for them to claim one day or not as they saw fit. I offer this book’s names in something of that spirit, an extra name that could be opted into or plausibly denied by each of these individuals as lives change over time. It also remains a way of asking readers to engage with the larger health and social issues being described, but to respect the privacy of individuals unless they have reached out first.16

The slow time-lapse stories unfolding in Mr. P’s album were also shaped by a gradually changing landscape. Erosion touched human bodies as well as their environs, atmospheres, and infrastructures. They all wore down in ways that were materially connected. In fact, Mr. P and I first started up our conversation while standing in the doorway of a stranger’s barn, watching the broken-down yellow school bus we’d been traveling on get pulled up a hill backward by another school bus. That road strained many engines, and bad weather chronically worsened already rough terrain. That particular afternoon, the hours sitting around the farm where our bus broke down felt like the opposite of a crisis. But that same trip for someone urgently needing medical care would have been a very different matter. One woman recalled how her surgeon planned to cut below the knee, but the vehicle carrying two necessary bags of blood sent by a loved one got stuck in flooded roads after a storm. The infection moved faster than the ambulance. By the time the blood delivery arrived, the surgeon had to cut above.

TRAVELING WITH SUGAR

One of the first expressions I heard for diabetes when I arrived in Dangriga was “traveling with sugar.” Sugar is a very common phrase for diabetes—though “traveling with sugar” is not a set label, just one possible translation. In Belize’s English Kriol, to “travel with” has long been a term for living with chronic disease.17 This striking turn of phrase stayed with me as I saw how trips in search of care were a significant part of how many people with diabetes spent time, often traveling by slow public transportation to far-flung clinics, hospitals, temples, or other destinations in search of materials “to maintain” themselves and support their family members. “Traveling with sugar” also echoed common reflections that living with diabetes could feel like being on a strange trip or a very long road, chronic routes that people had to navigate for themselves without knowing where it all might end up.

In Garifuna idiom, one could also “travel” in a spiritual sense, through forms of inner reflective work or metaphysical communication with visiting ancestors. That is why expressions like “to take a trip” or “to get a passport” can double as Garifuna euphemisms for death.18 I remember stopping by Ára’s house on the night before she died, its familiar rooms suddenly filled with children who had made the trip from Chicago when they heard the news. They told the nurse I was accompanying not to worry about checking Ára’s sugar unless she woke up again. “She is traveling now.”

If some of the people I met were traveling with sugar, I was trying to travel part of the way with them: to be worthy company in moments when people invited me somewhere, to write down what they offered up, to ground my questions, and to learn what I could from faraway libraries or locations abroad that might fill in some blanks about the deep divides between us and the uneven conundrums people faced. Foods, technologies, and medicines were also traveling. Like the movement of people, objects’ mobility could be capacitated or curtailed by larger infrastructures. Some of the most profound “travels with sugar” were the first journey across a room on a new prosthetic leg or learning to travel on one’s hands, people teaching each other to move again as bodies and worlds change.

An ambulatory anthropology of sugar draws attention to how differently we each circulated through the same infrastructures, and how my own comings and goings contrasted so starkly with the mobility of others. Sometimes, but not always, I could borrow a pickup truck and offer rides to the hospital for emergencies. I accompanied hitchhiking friends to doctors and glimpsed the terrible frustration along certain junctures as air-conditioned resort vehicles sped by, but I have also been a passenger in precisely such private vehicles that passed by good friends. There was no eschewing the tourist infrastructures I moved through and no avoiding their troubled histories and ongoing implications they carried. And, of course, traveling with sugar can mean all of this too, trailing charged colonial legacies: travel with money, pleasure, illicit gains.

Tourists were hardly the only ones coming and going. “Garifuna people, we travel,” Antonia told me emphatically. “We traveled from Africa.” For many proud members of the Garifuna diaspora, traveling is an important idea far beyond health alone. It signals a deep history of fierce persistence against ongoing dispossessions and today includes a diasporic community of more than three hundred thousand strong around the world. “Travelling the ocean under British control” is the first theme that Joseph Palacio highlighted in his oral history work, when he italicized the word to signal its meaning as both a specific historical practice and a more abstract ideal of active navigation through a matrix of oppression.19 “I Have Traveled” (Áfayahádina) is a well-known Garifuna song that describes the composer’s good fortune: “While she has traveled and seen the world, she chooses to remain in her home village.”20

Others wished for such luck. Reliance on medical technologies like dialysis often thwarted people’s plans to eventually return home. Some in U.S. cities even considered themselves in medical “exile,” stranded abroad with diabetes and its complications. Still others in Belize who were more tenuously connected to kin networks abroad nonetheless lived with full details of the medical specialists they could not reach. Even a modest job in a U.S. paper cup factory could open a world of retirement resources to be leveraged back home later, such as when one woman in Dangriga had her specialty diabetes prescription pills (unavailable in Belize for any price) delivered monthly via FedEx from a CVS Pharmacy in Chicago.

Traveling organizations like the Belize Diabetes Associations of New York and Miami coordinate with wider networks from across the Caribbean and Central America to bring care teams to Belize each year. Many individuals who contributed to this said they considered these kindred transnational communities as the publics—along with caregivers and families living with diabetes elsewhere in the world—that they hoped this project might reach. Accordingly, I have placed certain reflections meant for academics alone in footnotes and online, trying to find language that might also travel.21

Of course, the word sugar already contains many journeys and histories. One version of how sugar’s pivotal episodes altered the course of Garifuna history might go like this: Columbus planted sugarcane on what became the Dominican Republic in 1492.22 By 1505, the first slave ships arrived.23 The Caribbean archipelago at that time was one of the most heavily populated geographies on earth. By the late eighteenth century, some 90 percent of the Kalinago population and other Indigenous peoples of the Antilles had been exterminated by military campaigns and European epidemics, as island after island was converted into sugar plantations.

By the late eighteenth century, the last Indigenous-controlled sovereign territory in the Caribbean was Saint Vincent, an island strategically chosen as a fallback point because its mountainous geography allowed for fierce defense. It also became home to a growing community of mixed Indigenous and African ancestry (including men and women who escaped boat by boat from the sugar economies of surrounding islands), which colonial authorities soon labeled “Black Caribs.” This group that came to call themselves Garifuna24 defended their land against European invasions for nearly two hundred years, winning a long series of wars against the British. In 1796, the British military finally managed to exile the majority of the Garifuna families from their land, which they had called not Saint Vincent but Yurumein, “Homeland.” This violent dispossession occurred because the English wanted their land for a sugar plantation.25

There are at least two plants relevant to the topic of global diabetes that were growing on Saint Vincent on the day of Garifuna exile, both of which British companies would later sell back to the descendants of those Garifuna people who were packed into the hold of the warship called Experiment and its fleet. The primary one was sugarcane. But another was a weedier specimen with tiny pale flowers that the British had bioprospected from Turkey long ago—Galega officinalis, the botanical source for metformin, which is today the most widely prescribed diabetes pharmaceutical in the world.26

Westindische Inseln, 1848, with mainland Belize mapped as an insulin (island) of the British Empire.

An estimated three-quarters of the Garifuna population died during this forced removal from Saint Vincent to Central America, especially while being held captive on the isle of Balliceaux. Many of their ancestral crops were also lost during this time, although survivors managed to keep cassava plants alive in the ship’s hold, watering them with their sweat.27 But the majority of their medicines, foods, and vegetables fell into possession of British planters, who sent samples back to London for agricultural exhibits and testing by pharmaceutical companies. The British called this the Garifuna people’s “transition.”

In public health, the term epidemiological transition is often applied to explain the rise of chronic conditions (such as diabetes) in the late twentieth century.28 In contrast, this book aims to craft a troubled, interrupted, and slowed-down version of this transition story: one that approaches the uneven distributions of diabetic sugar in relation to the ongoing effects of colonial legacies and modes of knowledge making. To do so, it builds on the arguments of numerous scholars who have considered the interrelations between colonial violence and rising diabetes elsewhere in the world, and considers ethnographic realities in relation to these shape-shifting histories.29

No one factor alone can explain the way the odds have gradually been stacked against healthy agriculture in places like Belize. But if you take a step back and play the history over again slowly, there is a before and after to how food systems have changed. For Garinagu, some of the relevant episodes upon arrival in Belize could include many small incidents: The colonial creation and subsequent neglect of Garifuna land reserves. The year the farming demonstrators got defunded. The year the government stopped selling the variety of rice that people knew how to grow.

Many tracts of land have been sold to foreigners to cover diabetes medical bills. The changing kinds of foods sold in local grocery stores also each had a history. More recent shifts only compound much longer histories of dispossession: Back in the 1790s, British authorities had dispatched natural scientists to define racial markers in hopes of disproving the Garifuna’s dual ancestry as both Black and Indigenous in an effort to deny them legal rights to their ancestral territory. Even today, Garifuna people still struggle to be legally recognized as Indigenous by the state—part of a new era of land sovereignty struggles and agricultural transformations that this account explores, in relation to nutritional changes and gradually rising diabetes rates.30

For all that has changed since the days of Saint Vincent, there are certain disturbing continuities over the centuries: sugar remains a primary sign of violence and uneven injuries, and industrial profit continues to accumulate around preventable deaths and patterned land dispossessions. In this sense, the struggles with diabetes described in this book could be read as only the latest chapter in five hundred years of traveling with sugar.

In Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History,31 Sidney Mintz famously argued that the rise of a British “sweet tooth,” related to changing factory labor that drove global demands for sugar, could only be fully understood as part of a global system that relied on the exploitation of land and labor on sugar plantations in the Americas. Yet Mintz actually began his investigations on this matter with a much more granular mode of anthropological storytelling about Caribbean sugar: the individual life history, which narrated the experiences of one person’s trajectory working in cane. This approach revealed social dynamics without assuming any individual was modal or “representative” of a given population.32 Mintz’s later account of sugar as global commodity in Sweetness and Power was an attempt, he said, “to trace backwards” the norms he encountered in the course of individual life history work.

The realities of diabetes examined here might be considered living sequelae of the transformations that Mintz described, sugar out of place in modern history. In what follows, I try to bring these two ways of approaching the anthropology of sugar—individual life histories, and global histories of racial capitalism33—together in the same book. Talking with people and thinking with their own insights into their conditions, as my teachers João Biehl and Adriana Petryna show, “compels us to think of people not as problems or victims, but also as agents of health”34—and co-envisioned ethnography as an “open system” for public exchanges that may continue long after books end.35

In juxtaposing life histories with global stories of commodities in systems, the aim is an ethnographic version of world systems theory that stitches together glimpses of global processes and infrastructures with their living consequences for people. There is, inevitably, some trade-off in depth when trying to assemble bits and pieces from this broad scope, at times only gesturing toward enormous literatures with deep relevance—anthropologies of environmental change and food studies, ethnographies of medicine and global health, social studies of science and technology, settler colonial and postcolonial histories, debility and disability studies, work on maintenance and infrastructure, and Belizean and Garifuna cultural histories, among others. While a more narrow framing might make academic analysis easier, it would not do justice to the stories of individuals who are dealing with elements from all these intersecting arenas in trying to live with the erratic sugar in their bodies.

I approach such fraught storytelling guided by Mintz’s insight that none of us exists outside the global legacies of sugar—to the contrary, he argued, we are each related in ways that we might not understand. In this view, the uneasy position of my own whiteness is not something to be disclaimed. It is a constitutive part of the global legacies of sugar in question, and a role I occasionally perform as narrative foil.

Whatever else the diabetes journeys recounted in this book suggest, they are also haunted by thwarted and incapacitated travels: life-giving mobility that got occluded or made unthinkable for others, even while often available to me. It is painful to recognize that after all these years of trying to share connective experiences and find commonality with the people who appear on these pages, the places where our paths diverged may be more illuminating than any of the junctures where they joined up for a short while. The unjust gap between my “travels with sugar” and those of others also sheds light on chronic infrastructures much bigger than any of us—ones that you are somehow positioned by too.

In an aging world system, there are “remainders of violence”36 at play with power of their own, exceeding anyone’s conscious intent. But exactly what that meant (or might come to mean) for this story was not easy to name. The more that people taught me about their actual ways of living with sugar, the more these suggestive parallels with bloody histories seemed to both provoke and defy easy conjugation.

Sweetness and . . .

What?

ERRATA: METHODS AND MISTAKES

I have always been unsettled by errata: strange little scraps of text appearing at the edge of feature news stories and journal articles, like misplaced footnotes that set straight some error from a past edition gone by. The irony of errata is a fundamental one: by definition, corrigenda are uncorrectable corrections. The flawed template has already gone to press; revisions are no longer possible. All that is left to do is append, painstakingly detailing these mistakes and noting how they might be written otherwise for future versions. Errata are always details out of time and out of place, residues of errors coming to public awareness at least one issue too late. Yet it matters, not just technically but somehow ethically, to note for the record any mistakes observed too late to actually be fixed.

These thoughts about acknowledging unresolvable past errors stayed close in mind as I learned more about painful colonial histories and their material legacies across the Caribbean and Central America. But as I set out to do ethnographic work in Belize, a more immediate scale of concerns also began to take over my daily routines and attention. In addition to meeting people around town and visiting the local hospital, I also began going on home visits with caregivers from a local clinic. Those home visits often felt like observing not only a healthcare system, but also its gaps—diabetic sugar was part of people’s domestic worlds in ways that far outpaced its “medicalization.” I was very careful to repeat again and again that I was not a physician or a nurse (although people still called me both constantly). On these routes, I worked to act within the parameters of what a volunteer would be permitted to do in a U.S. caregiving situation; by way of a guideline, I would only participate in errands and practices that an amateur would be allowed to perform in U.S. homecare, terms that I knew from working in home care during college. But I sometimes found it unsettling how much expertise and medical power people were at times willing to allot to me. I was asked to do things like remove stitches and give insulin injections—which, of course, I did not do—but I had to draw firm lines about the medical forms I was not willing to wield. The mere fact of being asked to assist with these technical tasks when stopping by people’s homes was a discomforting window into what they were facing: many of those diagnosed with diabetes also worried that they lacked sufficient expertise to safely inject themselves or their family members with insulin at home. Yet that was what therapeutic “adherence” often required.

During this time, I tried to mark myself as an anthropologist by avoiding certain symbols of the medical profession—for example, I decided not to wear scrubs as an everyday uniform when accompanying nurses or doctors on home visits, even though I was asked to do so once by a clinic director, worrying this would deepen people’s confusion about my role. Meanwhile, other things I had used in the past to mark myself as an anthropologist—such as a notebook, clipboard, or paperwork—are all signifiers that anthropology shares with medicine. These items seemed to confuse people more about my connection to the healthcare system, rather than clarify my purpose. So my digital tape recorder became important to me during this time, as a marker of “not-doctor.” The tape recorder often made conversations more awkward but felt like an important tool to try to make sure that people were telling me things as a storyteller.

It became apparent that there was also a local notion of research ethics circulating. This was explained to me by my language teacher on my first day in one Maya village where I worked. She told me the last anthropologist who had worked in their village had not “given back,” and as a result he had met a bad fate. (And it happened that this professor was suddenly killed at a young age.) This was how some people in the community read his death, and she kindly said that she wanted to warn me from the beginning, so I could go forward only if I felt comfortable with the risk. Her tone was nothing like a threat—more like a disclosure of the risks this research could entail for me. Was this also a version of informed consent? If something happened, it would not be her acting, she explained—it was not like the metaphysics of obeah or human-directed witchcraft. The language and cultural knowledge itself had a force that could take lives as collateral for upholding the ethics and reciprocity of our relationship.

But less righteous lethal forces were also at work. The stakes of negotiating different ethical fields felt much greater once people I knew started dying. Once in a while, I would go to visit someone for an interview and find out they had died. In addition to wider circles of less intensive interaction (people I interviewed once or twice), there were fifteen people I began visiting once or twice a week, every week, for a year—the kind of gradually built relationship in which you really get to know a person. Thirteen of the fifteen have died since then. I had not at all expected this intensity in advance, and because these events became personally overwhelming, they also changed the kind of impressions I gathered. Sometimes writing my daily fieldnotes felt like attempting to cast death masks of people in their final moments, trying to capture something dignified about their lives before they were gone. At one point I tried to think of these as tributes or memorials; but they are also something more uncomfortable than that.

At this time, I also began paying more careful attention to the Garifuna death rituals that were happening around me. Messages received from the dead were part of how people situated their diagnoses from the hospital. Many Garifuna rituals centered around a notion of feeding the dead by cooking enormous feasts for ancestors that are thrown into the sea or buried in the sand. Since I was studying diabetes, this use of food seemed important because it often involved the very dishes that people living with diabetes were commonly advised not to eat—white rice, rich soups with coconut milk bases, desserts, and rum. The same foods being used to keep memories of the dead alive had become dangerous for the living.

I felt a deepening sense of undirected anger and ineptitude as numerous people with diabetes I had known died preventable deaths in the fatal fictions of “noncompliance.” Through experiences such as sitting with a mother who asked me to take a turn holding her son’s dead body, I came to understand something more about the ways a lost sense of security might become a chronic imprint or bodily change in someone. Shortly before I left, someone tried to break into the room next to where I was sleeping one night. I later learned that the thief had most likely been a child; nearby that night, someone else reported a break-in where the footprints in the sand looked too small to belong to an adult. Only ham and a loaf of bread were stolen; a laptop was left untouched. Afterward, I thought often of the little ham thief. What does it mean for a child’s hunger to coexist in plain sight of tourists’ luxury resorts? What happens when such profound inequalities take root over time? It was a context in which being any kind of white person left one with an unshakable sense of complicity, crucial not to disregard and impossible to escape.

I did not know how to process that sense of underlying danger and inequality. Here I was trying to understand medicine in the context of Garifuna notions of death while also becoming paranoid about my own. I lost twelve pounds in four days to an acute illness in April, then got pneumonia. And shortly after someone had tried to break into the nearby window, I found out that I was—by sheer coincidence—working in a clinic built on the exact place where an earlier white anthropologist who worked in the village had lived. I did not find out until late in my research that he was murdered in Belize. The figure of the killed anthropologist was therefore a disciplinary legacy in both places where I worked, which I came to feel unwittingly but inescapably connected to somehow. Just by choosing to stay in the midst of bad omens, I found myself also touched by a kind of Thanatos, which felt entwined with the offerings to the ancestors and other dead unfolding around me.

At some point, this unsettling context of my fieldwork became more than the methodological realities of my research, but also a central heuristic through which I was coming to understand the things I saw in Belize: medicine in the communities where I lived; the way people I knew there sometimes thought of their illnesses as inevitable and the imminence of death as intractable; the way this intimacy often became part of how they communicated with their ancestors through rituals, food, and songs; and the way people bore their losses, by redefining love and communication as something that only grew more powerful in the face of death. Maybe this was participant observation in a way too: I came not just to observe but also to partially participate in an intermittent reckoning with death.

For me, these methods came to feel like a postscript of obsessively studied mistakes—some of which I observed in global institutions’ policy documents, occasionally witnessed and at times felt complicit in, or myself felt mistaken for engaging with in the first place. Of course, to some extent errors are part of human relationships themselves and therefore inherent to anthropological research, perhaps even part of the conditions for ethnographic possibility and its “troubled knowledge.”37 Carl Jung believed that “mistakes are, after all, the foundations of truth,” while Salvador Dalí wrote of mistakes, “Understand them thoroughly. After that, it will be possible for you to sublimate them.”38 Yet that does not change the fact that I still considered or experienced certain events as mistakes, whether witnessed or my own. Many of their consequences are unfixable. But I like to think that maybe they can be appended in a limited way through what I write about them now.

If the following chapters started out with methods from the classic anthropological genre of life histories, many slowly turned into death histories—a painfully apt term I owe to Jim Boon.39 Some of these stories are just fragments someone wanted to share. But others, more sustained collaborations with those I at times came to think of as friends, are perhaps more like elegies.40 Garinagu have always written beautiful elegies, sung on disquieting scales across porches and in living rooms as well as ancestral temples. As Roy and Phyllis Cayetano describe, in such Garifuna lyrics, “people and events can be recorded in songs like little pictures which become public property and remain, long after the former becomes a matter of history.”41

There is a certain sense in which my writing now feels like a partial mirror held to such gestures of memory. Just looking at my field notes when I work at night, hearing the voices of dead friends from Belize in interview tapes, and looking at pictures from this project became an experience of constantly encountering ghosts and trying to find ways to engage the dead and their memory. The attempt feels heavily borne because of my sense of helplessness and complicity in being unable to prevent their deaths.42 Yet at this point, finding a way to tell these stories feels like part of my own ethical response to what I saw—maybe the only one still available. Trying to write feels not only like a postscript to the ethical dilemmas I encountered during fieldwork, but also like a gesture toward appending the lives of these untimely dead. These chapters are offered as corrigenda in the (hugely insufficient) sense of a place where they might still be alive.

But I cannot write about normalized death from the outside; there is no outside. I could only study the unequal systems I was caught in together with others and note our vastly different positions within them. Many understood the imminence of their own deaths much better than I did at the time, testing me as a channel to an imagined public record or wider stage with agendas of their own. Gestures of transformation pressed against the jagged edges of things that none of us could change, the playful and painful bound together. I never managed to shed the contradictory roles that have been part of playing the role of ethnographer since colonial times, though I tried to perform them more collaboratively: aspiring mediator, tolerable resource boon, academic authority, implicated naïf.

In some especially tense moments, I sometimes found my face freezing into an overwrought smile in an effort to appear at least well intentioned in my foolishness. Garinagu men wear masks with smiles like these when they dance the Jankunu dance around Christmas, with seashells stitched to their knees. They make the white masks out of cassava strainers painted pale pink and decorated with forced frozen smiles, satirizing the colonial absurdity of slave-owning white people and uniformed soldiers.43 Above their whiteface the dancers wear hats decorated with garish paper flowers and bits of mirrors. But maybe these Wanaragua masks also capture more than they mean to, or at least something they do not purport to be rendering. There is a certain helpless white smile of someone who wants to be good but does not know how to face the violence of the past they are tied to, which resembles both the mocking Jankunu mask and my strained smiles in those moments. (Upon meeting a stranger, many old Garinagu women will stare down your cursory smile and not return it until they know you well enough for you to deserve it. I admired the wounding honesty of this habit.)

Masked character in Jankunu (Wanaragua) performance.

I have learned a great deal from the writings of anthropologists who work to unmask systems of structural violence. But for my own project, I gradually felt a more disquieting truth when acknowledging that I did not even know how to unmask myself.

SLOW CARE

Many of the individuals I met in Belize came to number among the millions of worldwide deaths now attributed to diabetes each year.44 Somehow, the slow-moving quality of chronic conditions like diabetes—what U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon once called a “public health emergency in slow motion”—seems to make it only more daunting to imagine reversing its spread in the future.45 A range of disturbing statistics suggests that today’s policy approaches have not slowed the rise of global diabetes rates or mortality; to the contrary, these figures appear to have accelerated worldwide each year they have been tracked. According to the latest projections of the International Diabetes Federation, the condition “affects over 425 million people, with this number expected to rise to over 600 million within a generation.”46 No health institution that I am aware of predicts that current interventions might be able to curb the problem on a population level. In this light, there is global resonance to what was probably the single thing I heard repeated most often by the Belizean and Garifuna individuals with diabetes who contributed to this project: “It is my children I’m worried about.”

Every story in the rest of this book is really the same story that Mr. P taught me to see—chronic strains that slowly cause bodies to fall apart and the people trying to keep each other together. In fact, each chapter retells that same story again, from a different angle. When it comes to diabetes, this repetition is no narrative accident. Fatigue and relentless repetition are the defining features of what makes diabetic sugar harrowing—people trying to stave off bodily loss and failing organs day in and day out, year in and year out, over and over again, utterly foreseeable, likely coming anyway.

It was only people’s work of maintenance, caring for each other in the face of all this, that never stopped surprising me. When one new mother told me that her dream with diabetes was to try to maintain for her kids, I paused expectantly, waiting for her to finish. She shook her head. “And so I must work hard to keep myself,” she said. I waited with my pen poised for her to complete the sentence—to keep herself healthy, to keep herself going? But as we sat in silence, I realized that she meant the expression simply as it was—to keep herself, all of herself: the feeling in her nerves, her fingers and feet, eyesight, life. I closed my notebook.

A slow epidemic both is and is not like other forms of violence.47 It plays with time. It breaks down stories, as Rob Nixon memorably wrote in his description of “slow violence”48—and unevenly wears on different bodies, Lauren Berlant emphasizes of “slow death.”49 But writing can play with time too—allow for taking a step back and making visible processes and their errata over a “long arc,” as people and places intimately shape each other. If the slow violence of sugar continues to saturate many of these stories, its harms demanded the kinds of practices I often saw in Belize, which I came to think of as slow care—ongoing and implicating joint work in the face of chronic debilitation.50 That is not a caveat. It is the guiding frame for the rest of this book.

Galega officinalis, the plant source that became the blockbuster diabetes drug metformin, at the Kew in London.

Looking back at these families’ survivance51 with diabetes unfolds the small moments that make up this epidemic—allowing a chance to pause and reflect on how these realities came to be, and to try learning from the moments of remaking and recovery already underway. Their struggles bring to life Mintz’s argument that the point of drawing out social histories of sugar is to remind each other that “there is nothing natural or inevitable about these processes.”52 In contrast to how bleak many global projections can make the situation feel, the Belizeans profiled in this book taught me to approach the rise of epidemic diabetes not as a settled past or an inevitable global future—but instead (as an anthropologist once wrote of co-envisioned struggles elsewhere) more like “a story we are all writing together, however we appear before one another—ready, set, go.”53