Читать книгу Blue & White Japan - Amy Sylvester Katoh - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

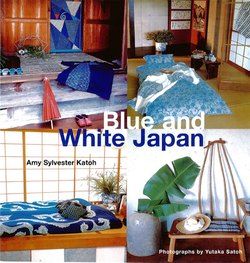

ОглавлениеLiving with blue and white means the focus is on simplicity. Here, peace prevails in the entrance-way of the Sanshiro Ikeda house, moved from Toyama Prefecture twenty-five years ago and faithfully restored in Matsumoto. The lines of the alternating slats of dark wood on the sliding door are repeated in the bamboo pattern of the hemp-fiber noren curtain created by the late Keisuke Serizawa, stencil designer, dyer, and Living National Treasure. On the massive chest are an old quilt and a furoshiki, wrapping cloth.

Rags and riches fill the entrance of the Kupciunas house. Calligraphy on a scroll of washi, Japanese handmade paper, by Naoaki Sakamoto of Paper Nao. The ragweave slippers are from Wajima. A Thai horse looks on.

Entrances not only welcome visitors, they also reflect the taste of those who live within. They are considered the face of the home. What better place to introduce a blue and white sensibility? Blue and white has its own energy and it conveys a message of simplicity and order. Start with basic materials-an Imari umbrella stand, a favorite porcelain hibachi brazier, some antique textiles-then use them in fresh ways to add texture and character to otherwise anonymous spaces. Try wrapping a basket of flowers and branches in an old futon cover of patched indigo. Add a touch of whimsy to an entranceway floor with an arrangement of ragweave sandals and heavy workman's footwear. Consider using noren, the split curtains traditionally hung in shop doorways, to delineate space and serve as creative door dressing. Then, in the Japanese way, change them with the seasons: sheer fabrics for summer, thick cotton indigo in cold weather. The entrance is a place to make a statement about what you love and what gives you energy. Share that energy with all who enter by making it an expression of your individuality. Blue and white is the message. The entrance is the place to communicate it.

Wooden puppet's feet, workman's footwear, and old ragweave sandals join forces.

A floor-to-ceiling indigo bamboo grove with openings cut for arrangements of hydrangeas in front of a sculpted concrete staircase and a child's kimono.

Harumi Nibe, in a tie-dyed indigo hat by Ryoko Kodama, greets guests with her Labrador, Tokiwa Gozen. Next to her, a blue and white hemp curtain fragment draped over a freshly cut bamboo lintel serves as a new take on traditional noren. Transplanted to Tokyo from Shikoku, Nibe-san is a flower and food artist who brings the rich flavor of country sensibilities to whatever she does. Her style is imbued with the Japanese appreciation for rustic and natural things.

Gossamer noren cover a storage cupboard in the display room of Kosoen, an indigo dyer's workshop in Ome, Tokyo. Above the cupboard, a rice-straw bale of fermented indigo sits next to rolls and skeins of undyed cotton thread. On the floor, an old back basket filled with lilies. In the next room are the indigo vats.

A converted temple in Sakakitamura, Nagano, is home, workplace, and showroom for Kibo and Keiko Nomoto, potter/indigo dyer and textile artist respectively. Provisions for going out include an indigo traveling coat, paper umbrella, and covered clogs. Keiko Nomoto's own indigo patchwork collage brightens the wall.

Artful doors. Handsome definers of space that invite us to enter a house or a room, noren can also turn a doorway into a frame for a fluid work of textile art.

Noren are usually dyed with indigo and made of cotton, and sometimes of hemp. They are suspended from a bamboo pole across the front of traditional Japanese shops, where they serve to announce both the name and crest/symbol of an establishment and that it is open for business. When the shop is closed, the noren is removed.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, streets were lined with shops whose vibrant noren were a compelling testament to the dyer's art. While modern stores do not usually hang noren above their entrances, enough noren- graced doorways still exist to offer practical art opportunities to indigo dyers and designers who seek a canvas on which to exhibit their talents.

Noren in banana fiber and indigo, spun, woven, and dyed by Toshiko Taira of Okinawa, who has led the movement to preserve the ancient craft of banana-fiber textiles, bashofu.

Tie-dyed indigo noren hanging in the doorway of the Kakinoki antique shop in Tokorozawa.

Sheer magic. An appliqued noren of indigo mosquito netting by Kazuko Yoshiura.

Straw cushions on the bay-window seat are favorite spots for tea. Shisa, temple dogs or lions, by Joga Shima, and a large blue and white covered bowl by Kyoshi Matsuda are dwarfed by the massive wall of local travertine in the fireplace.

The best rooms have a certain serenity and clarity of purpose. To the Japanese way of thinking, a main room where guests may visit has to be versatile and beautiful. It should also provide a feeling of well-being. Translated into a Western setting, this means the sort of uncluttered living room where you can put your feet up if you feel like it, throw a party when the spirit moves you, or just sit quietly by the window and daydream, yet always feel refreshed and sustained by things you love. Nestled on a hill in Okinawa overlooking the East China Sea, the room at left meets all these criteria. It is a living room where one is meant to live simply and well. The ever-changing blue and white of sea and sky are an evolving mural, so furniture and other decorative elements have been reduced and downplayed. Instead, the soaring windows provide a spirited sense of place through the use of local craftsmanship in the construction and the addition of blue and white Okinawan textiles and ceramic accents. Used in tandem with other things, blue and white lends a room a relaxed elegance, making it a room to remember.

A pile of antique textiles waiting to be used.

Country blues and whites in a mountain house in Kobuchizawa. Stretched along the sofa back is a 19th-century horse trapping. Quilted pillows in homespun cotton by Kazuko Yoshiura add comfort. An old, checkered fighting-dog blanket from Shikoku is under the table. Dogfights are now out lawed.

Mood indigo in Haruri Ginka Gallery in Kawagoe. Under beams hung with dyed mosquito netting, a mysterious wooden llama sculpture by Hideki Maegawa shoulders an old yukata robe made of patched tenugui hand towels, while overseeing other whimsical Maegawa creations: tables and benches of old ships' timbers and other found objects, which he uses to create original furniture for living and laughing.

A quirky sculpture by Seiji Nibe and a banner with a design of carp climbing a waterfall, a traditional symbol of strength and bravery, add panache to the entranceway of an apartment.

A living room that welcomes friends to sit down, relax, and share stories among the owners' favorite things-books, family photos, rustic New England footstools, and, of course, blue and white pillows and floor cushions. The lamp on the right is by lsamu Noguchi. An indigo patchwork quilt does double duty as a rug, and a large lacquered tub, bought at a flea market years ago, serves as a coffee table.

18th-century Japan in the 20th-century folk-art museum house of Sanshiro Ikeda, collector of furniture and crafts from Japan, England, and Korea. Here, a child's oak school desk and chair, an Imari vase, and a striped indigo textile with a family crest form a serene still life.

Blue and white details

Simple things well arranged offer quiet inspiration. It is on details that the eye lingers-the enigmatic blue of a long striped textile against a sand-colored wall, the velvety white of a flower in a small Imari vase, the contrast of a checkered textile against richly worn wood. There is no substitute for attention to details in the creation of understated, relaxed style. Using blue and white ceramics that are more lovely than priceless, textiles that have individuality and charm above pedigree, adds intriguing character to a house. For fine-art devotees, imperfection is a flaw, but for those who love Japanese blue and white, a neatly mended antique cloth and a chipped plate carefully repaired and handed down through generations have stories to tell. They are intriguing because their lumps and bumps and mends reveal they are truly valued and cherished. Living with such objects is a joy. A tray of mismatched sake cups, a collection of porcelain shards, a favorite basket of fabric bits and pieces-all of these will brighten a room and evoke a warm response. A Japanese blue and white textile or ceramic has its own integrity, yet it interacts harmoniously with other objects and gives nourishment to all.

A contemporary bamboo basket from Shiga Prefecture filled with blue and white ceramic scroll ends.

Calligraphy practice on an antique glass-covered basket among scattered zabuton covered in vintage kasuri patterns. A ragweave farmer's vest in blue and white with red accents waits to be slipped on as the afternoon grows cooler. On the table, the dish and brush holder are old lmari, while the teapot and cup are contemporary.

Floor cushions

No house in Japan should be without zabuton, versatile floor cushions that can create an instant seating area and then be stacked away once guests depart. Zabuton are traditionally filled with kapok or cotton padding.

Zabuton covered in blue and white kasuri, ikat or patterned cotton, and modern textile adaptions of old indigo designs in between.

A giant red carp splashes up from a colorful textile on the sofa in the Hoksbergen living room. In front, a clever table constructed of lunch delivery boxes and glass. Below, a clouds-and-waves porcelain hibachi features a playful dragon.

Something old, something new around the irori, a sunken open hearth, in a Yamanashi country house. The splendid heart-stopping cushions of indigo crosses on white hemp are by Takumi Sugawara, perhaps the most original tsutsugaki, freehand design, textile artist working today.

Waves and carp plaster design by Hitoshi Kutsukaki on a roof gable in a Karuizawa house; stone gods on ragweave obi sash; a striped horse rein used as edging for tatami; Meiji-era (1868-1912) glass lamp shade and lmari electrical fixture at Kakinoki Antique Gallery.

All in the details. Japan, blue and white and otherwise, is an aggregate of details. Fine lines in small places, moods, moments. Focus with a Western eye on the grand picture and you may miss the quiet corners where the Japanese eye for particulars shines through. Look at the unheralded surfaces: the plasterer's roof gable, the tatami edging, the electrical outlet, the brush stroke on a piece of porcelain, the worn grain of a wooden tray. Peek at the under-kimono if you can. That is where the spirit is revealed.

Handmade blue and white rope in an open-weave basket.