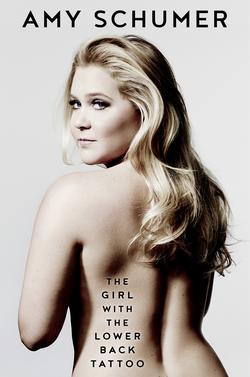

Читать книгу The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo - Amy Schumer, Amy Schumer - Страница 12

Dad

ОглавлениеWhen I was fourteen my dad shit himself at an amusement park.

It all went down one fine summer morning when he took Kim and me to Adventureland, which is exactly what it sounds like: an amusement park filled with adventure, as long as you’ve never been on an actual adventure or to an actual amusement park. I’d fantasized about the trip the whole week, dreaming about my two favorite rides: the pirate ship and the swings. Granted, they were two of the tamer rides at the park, but for me, they were at the absolute outer limit of my comfort zone. I liked the rides that gave you that feeling of weightlessness that shot from your stomach right down to your vagina when the ride dropped, but I’d never enjoyed a ride that went upside down or spun around until I puked, and I still don’t. I guess you could say I have a low tolerance for fear in general.

The movie Clue terrified me beyond belief as a child. I slept with a pillow on my back because the chef in that movie was stabbed in the back with a huge kitchen knife. Not gonna happen to this gal; just try to get a knife through this pillow, I thought. As if a murderer would enter my bedroom at night intent on stabbing me in the back, see that there was a pillow there, and cancel his plans. I used a similar tactic after hearing about (but not seeing) the movie Misery. I slept with pillows covering my legs in case Kathy Bates got a late-night urge to drive out to Long Island, break into my home, and beat my legs with a mallet. Maybe this is why I always slept with (still sleep with) all my scary-looking horror-show stuffed animals. For protection.

Suffice it to say, I was a major scaredy-cat. In fourth grade, I had a talk with the school psychologist about all the things that actively terrified me. I wasn’t sent to see him by a concerned teacher, I actually asked to see him. I was probably the only nine-year-old in history who requested time with a shrink. After our session, he handed my mom a list of all my fears. This list included earthquakes and tapeworms, which didn’t usually come up much where I lived, but my brother was learning about them in school and he couldn’t resist the urge to convince me I was nothing more than a sitting duck who was 100 percent going to get eaten alive from the inside by a worm. Highest (and most memorable) on the list, however, was the specific fear that I’d accidentally churn myself into butter. This was inspired by a creepy antique children’s book called Little Black Sambo, which is one of those stories from the simpler, more racist times of yore when people wrote frightening, insulting tales to help children fall asleep at night. It was highly popular back in the day and has since been rightly banned or taken out of circulation. But my mom had a copy lying around. It’s about a boy who goes on an adventure and ends up getting chased by tigers, who circle and circle around a tree so fast that they churn themselves into a pool of butter, which the boy then takes home for his mother to use to make pancakes. Like ya do. Anyway, I was always riddled with fear that I’d somehow be transformed into melted butter, which now doesn’t really sound like that much of a bummer. It sounds more like how I’d like to spend my last twenty-four hours on this earth.

Anywhoozle, the morning my dad was going to take us to Adventureland, I woke up and got dressed in denim shorts that stopped just above the knee (crazy flattering) and a long T-shirt with the Tasmanian Devil on it, to let people know what was up. The shirt had to be knotted at the side because it was the early nineties and that’s how you rocked out then.

It was not usual for my dad to take us on fun outings, but our parents had recently divorced, so we’d started spending solo time with him. This way, we could sneak in some fun, and he could sneak in feeling like a parent. He picked us up in his little red convertible around ten a.m. (even after he lost everything, he still always drove a convertible). I sat in the front because the back was too windy, and I convinced Kim that she’d like it better. It was about a forty-minute drive from our house, but it felt like four hundred because of the anticipation: the dozen or so rides, the limitless Sour Powers, and the arcade games just inside the park!

My dad always made me feel super loved and did the best he possibly could, but when I was a kid, his identity confused me. He wasn’t the golf-playing, beer-drinking family man I saw on TV or in my friends’ kitchens. He wasn’t so easily labeled – or so easily understood. When he was younger, he’d been a wealthy bachelor living in 1970s New York City – when it was also in its prime. He’d shared a penthouse with his best friend, Josh, who was a well-known actor at the time. He did drugs and slept with girls and enjoyed every moment of his life. When he met my mom, he said good-bye to that lifestyle. Kind of.

Throughout my childhood, he was always in shape – tanned and well-dressed. He was an international businessman, frequently traveling to France, Italy, Prague, and I’d know he’d returned home from a trip before I saw or heard him as his smell was so potent and gorgeous. I thought it was a mixture of expensive European cologne, a faint smell of cigarettes, and something else I didn’t yet recognize but later discovered was alcohol.

I never knew my dad to be a big drinker. I never saw him and thought he was even a little buzzed. If you don’t know the signs, then they can’t be there. I remember coming home from school and seeing him passed out naked on the floor, but not putting two and two together. I remember that he once apologized to me for missing a volleyball game that he was at, but I just thought, Oh, forgetful Dad! I knew he smelled like scotch, but I thought nothing of it. (To this day when a guy I’m with is really hungover or drunk, the smell reminds me of my dad, as I warmly cuddle him closer. When I tell the guy, he laughs, thinking I’m joking.)

I only later found out that my dad was as serious an alcoholic as they came. He needed to go to detox several times when we were children. To his credit, he was clever with his addiction. He only drank when he traveled or when we slept, so … all the time and every night. The only thing that slowed down his drinking was multiple sclerosis.

He was diagnosed when I was about ten and was soon in the hospital for a while since the disease hit like a tidal wave. It started with a tingle in his feet and fingers and grew to complete numbness and pain in his legs. When he finally got out of the hospital, he kind of went back to normal. I didn’t think about his illness and no one brought it up again. I loved my dad, but like any self-obsessed teen, I wasn’t worried with his mortality. Even though I saw him lying in the hospital bed in pain, I still thought of him as invincible. The morning he picked us up to go to Adventureland, I had pirate ship rides on the brain and can’t say I was too concerned about his health.

When we pulled up to the gates of the park, we ran to the high-flying swings and got in line. It was a little chilly, so it wasn’t too busy, which meant that we got to go on the ride two or three times in a row before moving on. I loved those swings because I could pretend I was fearless and twist my chair around and around before they shot up in the air to begin the ride, spinning me high in the sky.

I wanted to beeline to the pirate ship, but Kim wanted to go on the big scary roller coaster. We had all day, so I said fine, even though roller coasters brought me zero joy. Being jolted around and the yelling and the possibility of dying didn’t – and still doesn’t – do it for me. I hated creeping up the hill at a painfully slow pace only to shoot down and hear the screams of all the people filled with regret for coming aboard. But Kim liked them. And I liked Kim. And since I was the big sister, I wanted her to always think I was brave, so I pretended it was no big deal and got in line.

But to be honest, I also wanted to wow my dad. He knew I was a complete chickenshit, and I thought he might notice and say something like “Hey, Amy … you going on that ride was very cool and interesting.” He loved things like skydiving, which I eventually did when I was older, also to try to impress him, even though I hated every single second of it. So there we stood in a long line that felt like it was moving too fast. I hunched over a bit, hoping I wouldn’t meet the height requirement for the ride, but no such luck. I continued to hope that the roller coaster would close down for the day right before we got up to the front, or that there would be a lockdown on the park for a missing kid. There were thousands of kids there. Couldn’t just one of them get lost? But alas, no, we were next.

“Do you want to sit in the front car?” the six-year-old-looking kid operating the ride asked us.

“YES!” Kim yelled.

I looked at my dad, who was giving me a most-likely-sarcastic thumbs-up. “Yeah,” I added, even though Kim had already hopped in the front.

“I’ll be watching you girls!” he said ecstatically.

We waved to my dad as we started creeping up Suicide Mountain, or whatever the roller coaster was called.

I don’t remember much of the next two minutes, but finally the car stopped and I opened my eyes. The only silver lining was that I didn’t get physically hurt, and it was a great way to practice dissociating – something my siblings and I all perfected by our early teen years. We climbed off, and Kim was thrilled. She’d had the time of her life.

I can’t speak for the other maniacs on that ride, but for me, the roller coaster was traumatic. When I walked down that ramp I felt as though the president should have been at the bottom waiting to give me a medal for valor. But there was no medal; just my dad, smiling at us.

“There’s no line!” Kim shouted. “Let’s go again!”

And so we went, and we went and we went. Each time my dad cheered us on from the bottom. We must have ridden that thing five times when we reached the end of the ride and he wasn’t there.

“Where’s Dad?” Kim asked.

I told her, “He’s probably getting us candy or something.”

While we waited for him, we rode the ride again and again and again. After the twelfth go I was feeling real ready to get on that pirate ship, which was the main adventure I wanted to have in this land. Kim was raring to go again, but I had to stop. I thought it might be nice to take a break and maybe have kids someday, and I was sure Dad would meet us when he was done doing … What was he doing?

At that point in time, I hadn’t yet realized how funny my dad is. Most of the things he did or said flew right over my head, and everyone else’s for that matter. His sense of humor was so dry that days would pass before people realized he’d insulted them. He threw out perfect one-liners under his breath while talking to waiters or bankers or my mom – and no one heard them but me. Once my grandma was talking to him, and she said, “If I die …,” and he corrected her slyly: “When …” He was even dark with us as children. I remember walking into the kitchen one time and seeing him pretending that I had just caught him in the act of putting our dog, Muffin, in the microwave. He had a way about him that made it seem like nothing could ruffle his feathers or surprise him.

So that day while Kim and I sat on a bench and waited for my father, I saw a new side of him. We waited and waited. I put stupid braids in Kim’s hair and made her give me a hand massage until he finally reappeared. When he walked up to us, the first thing I noticed was his expression; he was panicked and defeated at the same time. The second thing I noticed was that he didn’t have pants on.

Kim didn’t observe any of this because she immediately asked, “Can we get fudge?!”

“Sure,” my dad answered.

He and I looked at each other. I was speechless. His T-shirt, which was soaking wet along the bottom half, was long enough to cover his underwear, but his pants were long gone.

“We need to go, Aim,” he told me very calmly.

I thought about asking something reasonable, like “Where are your pants, Dad?” But he looked in my eyes and communicated that I shouldn’t ask any questions. I went into the country-store-themed shop and got Kim her fudge, and then we all walked briskly to the car. I didn’t look to see if anyone was staring. I only watched ten-year-old Kim, who was fully enthralled by every bite of her treat. Does she really not see that he’s pantsless? I know it’s called Adventureland but I don’t think those adventures involve men over forty dressing like Winnie the Pooh after a wet T-shirt contest.

We’d just gotten very close to the car when a breeze hit and sent the smell my way. It was shit. Human shit.

It was then I realized, Oh, my dad shit his pants. Okay. I quickly leveraged this opportunity to look like a selfless and charitable sister. “You can get shotgun this time, Kimmy!” I was quick on my feet.

“Really?!” she answered. She was so excited to get this privilege that it kind of broke my heart. Amusement park fudge AND shotgun? She couldn’t believe her luck. Little did she know she wouldn’t be able to enjoy eating that fudge for much longer, or possibly ever again.

We climbed in the car, me in the back, Kim up front with my dad. As he put down the top, I looked in the side mirror and saw Kim’s nostrils start to flare. She’d picked up the scent. The most silent car ride of my life began. The fudge sat in Kim’s lap for the rest of the ride and her head slowly crept further and further in the direction away from my dad. The entire top was down on the car, but she still felt the need to hang her little head out the side. She looked like a golden retriever by the time my dad pulled up to our house to drop us off.

I was so impressed with her for not saying anything. What a good girl, I thought. She kissed my dad on the cheek and thanked him and ran into the house, her face the same exact hue as Kermit the Frog. I hopped out and held my breath to kiss him. I started to walk up our driveway when he called to me.

“Aim!”

I turned and answered, “Yeah?”

He took a breath and said, “Please don’t tell your mom.” I nodded.

The saddest realization I’ve had in my life is that my parents are people. Sad, human people. I aged a decade in that moment.

THE SECOND TIME my dad shit himself in my presence, I didn’t have a roller coaster to keep me from witnessing it. It was right in front of me. Well, more to the side of me.

It was four years later, the summer before I left for college, right before I got on a plane to Montana to stay with my older brother, Jason, for a couple weeks. I worshipped Jason and was always trying to hang out with him. He is almost four years older than me, and as far as I was concerned, he should have won People magazine’s most intriguing person of the year, every year. He was a basketball prodigy in his early teens but suddenly quit in high school because he didn’t want to live up to other people’s expectations anymore. He was curious about things like time and space, and genuinely considered living in a cave for months and being nocturnal. He became an accomplished musician without telling anyone. He didn’t go to his senior year of high school, choosing instead to earn the credits needed for graduation by driving cross-country and writing about it – somehow convincing the principal of our high school and our mother that this was a great idea. I know this is sounding like that Dos Equis ad that glorifies the eccentric old guy with a beard, but the point is I have been crazy about Jason since I was born and I always wanted to be a part of whatever unusual existence he was living. So I went to hang out with him any chance I had.

At this particular time, my dad was on a kick of wanting to do “dad stuff” for me, so he asked if he could drive me to the airport. When you have MS “dad stuff” becomes playing bingo or giving you rides places. It was midafternoon when he picked me up to head to JFK.

When we got there, I pulled my giant suitcase out of the trunk of his car and navigated the airport entrance without his help. This must have looked strange to other people, seeing this strapping man watch his eighteen-year-old daughter lift and tote her giant suitcase all by herself, but they didn’t know he was sick. I didn’t really understand the symptoms of the disease, but I did know that it slowed him down, that even if he looked normal he could still be in a lot of pain, unable to do the small physical acts he used to do with ease.

My dad accompanied me as I juggled my bags and checked in, and everything seemed fine. It was pre-9/11 so he could walk me to the gate, and that’s exactly what he wanted to do. He kept saying, “I’m going to walk you to the gate.” I think it was a big deal for him, because he never did stuff like that for me. That was a mom-type job. But I was glad for his company, because even though my list of fears had definitely gotten smaller by this point in my life, I was still pretty terrified of flying.

We both went through security, shoes on – the good ol’ days – and started walking down the long hall to my gate. That particular terminal was under heavy construction at the time, so we had to be careful where we walked. We still had a ways to go when my dad took a sharp right turn and beelined it to the side of the hall. I stopped walking and turned to see what he was doing. He shot me a pained look, pulled his pants down, and peed shit out of his ass for about thirty seconds. Thirty seconds is an eternity, by the way, when you’re watching your dad volcanically erupt from his behind. Think about it now. One Mississippi. That’s just one.

People quickly walked past, horrified. One woman shielded her child’s eyes. They stared. I yelled at one chick passing by, “WHAT?! Keep it moving!”

After he had finished, my dad stood up straight and said, “Aim, do you have any shorts in your bag?”

I opened my suitcase and grabbed a pair of lacrosse shorts. I handed them over, thinking, Damn, those were my favorite. He threw his pants in the trash and put the shorts on. I went in for a top-body hug good-bye. I didn’t cry, I didn’t laugh, I just smiled and said, “I love you, Dad. I won’t tell Mom.”

I started to walk away from the whole scene when I heard, “I said I’d walk you to the gate!”

I turned around to see if he was joking; he was not. To the gate we walked. I was mouth breathing and shooting dirty looks at anyone who dared to stare at him. Once we got to the very last gate in the goddamn terminal, at the end of a very long hall, he kissed me good-bye and left.

Normally when I would board a plane, the first thing I would do was worry about how scary takeoff would be and try to think of ways to distract myself from the anxiety. But that day, I sat on the plane thinking about nothing. My mind went blank. It was too painful. I didn’t think about my fearless father, who was dealing with a mysterious disease. He used to breeze through the airport in a cloud of expensive cologne and flashy watches, and now he’d been transformed into this anonymous, helpless guy who lost control of his bowels in the airport while his teenage daughter watched. He didn’t wince or let me see him sweat even once. I mean, he was drenched in sweat. Physically he was being taken over by MS, yet on the inside he was still as brazen as ever. But I didn’t think about any of that. I just stared out the window for five hours, fully numb, until I got off the plane in Montana and hugged my brother longer than he would have liked.

I tried to talk about these two shitting incidents onstage. So many parts of these stories are so disturbing that they make me laugh – because it’s too much to digest any other way. The image of Kim’s head leaning out of the car, the image of me standing next to my pantsless father and the trolley that carted people around Adventureland. I look at the saddest things in life and laugh at how awful they are, because they are hilarious and it’s all we can do with moments that are painful. My dad is the same way. He’s always laughed at the things that are too dark for other people to laugh at. Even now, when his memory and mental functioning have been severely impaired by his MS, I’ll tell him his mind is a pile of scrambled eggs and he will still laugh hysterically and say, “Too true, too true!”

My dad never shows any sign that he pities himself. He never has. He’s not afraid to look dead-on at the grim facts of his life. I hope I’ve inherited this quality of his. I’ve only seen him cry once about his disease, and that was very recently – when he learned he’d be getting stem cell treatments that would help him feel a lot better, and maybe even help him walk again. That day, he sobbed like a baby. But never before.

I have wonderful early memories of spending time with him at the beach. We were beach bums, and he was a sun worshipper. If it was January and the sun was shining, he’d douse himself in baby oil and sit outside in a lawn chair. He was tan year-round. And if it was summer, we’d get in the ocean early in the morning and get out after the sun went down. We’d body-surf together; that was our thing. All I wanted to do was take a wave in further than him, but it never happened. I even cheated, standing up and running a little to catch up, but no, he always won.

The most joy I remember feeling as a kid was when a storm was coming and the waves were big. Other people were scared and stayed out of the water, but not us. Not even when the ocean was angry and pulling us sideways. We would have to get out and walk half a football field on the beach before it swept us all the way down the shore again. We swam out against the current and caught the best waves of the day. Nothing kept us out – not rain, not my mom yelling, nothing. I can still picture him looking young and healthy and strong, with his bronzed skin and his black hair soaking. For some reason, I wasn’t afraid. Maybe it was because I was with him. Next to him, I was invincible.