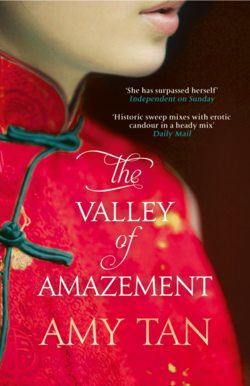

Читать книгу The Valley of Amazement - Amy Tan - Страница 10

CHAPTER 3 THE HALL OF TRANQUILITY Shanghai 1912 Violet—Vivi—Zizi

ОглавлениеWhen I stepped down from the carriage, I saw the gate of a large house and a plaque with Chinese characters spelling “Hall of Tranquility.” I looked up and down the street for a building with the American flag.

“This is not the right place,” I said to Fairweather.

He returned a look of surprise and asked the driver if it was indeed the correct address, and the driver affirmed that it was. Fairweather called for assistance from those by the gate. Two smiling women came forward. One of them said to me, “It’s too cold for you to stand outside, little sister. Come in quickly and you’ll soon be warm.” Before I could think, they grasped me at the elbows, and pushed me forward. I balked and explained we were going to the consulate instead, but they did not let go. When I turned to tell Fairweather to take me away from there, I saw only shimmering dust floating through the sun’s glare. The carriage was moving at a brisk pace down the road. Bastard! I had been right all along. It was a trick. Before I could think what to do, the two women locked their arms in mine and moved me forward more forcefully. I struggled and shouted, and to everyone I saw—the people on the road, the gatekeeper, the menservants, the maids—I warned that if they did not obey me, my mother would later have them jailed for kidnapping. They gave me blank-faced stares. Why didn’t they obey? How dare they treat a foreigner this way!

In the main hall, I saw red banners hung on the walls. “Welcome Little Sister Mimi.” The characters for mimi were the same ones used in my mother’s name for “hidden.” I ran to one of the banners and pulled it down. My heart was racing and panic choked my throat. “I’m a foreigner,” I squawked in Chinese. “You are not allowed to do this to me …” The courtesans and little maids stared back.

“How peculiar that she speaks Chinese,” a maid whispered.

“Damn you all!” I shouted in English. My mind was racing and all in a jumble, but my limbs were sluggish. What was happening? I must tell Mother where I am. I needed a carriage. I should notify the police as soon as possible. I said to a manservant, “I will give five dollars if you carry me to Hidden Jade Path.” A moment later, I realized I had no money. I became more confused by my helplessness. I guessed they would keep me here until five o’clock, when the boat would have sailed away.

A maid whispered to another that she thought a virgin courtesan from a first-class house would have worn nicer clothes than a dirty Yankee costume.

“I’m not a virgin courtesan!” I said.

A squat woman of around fifty waddled toward me, and by the watchful expressions on everyone’s faces, I knew she was the madam. She had a broad face and an unhealthy pallor. Her eyes were as black as a crow’s, and the hair at her temples had been twisted into tight strands that pulled back her skin and elongated her eyes into catlike ovals. From her lipless mouth, she said, “Welcome to the Hall of Tranquility!” I sneered at how proudly she said the name. Tranquility! My mother said that only second-class houses used good-sounding names like that to convey false expectations. Where was the tranquility? Everyone looked scared. The Western furniture was shiny and cheap. The curtains were too short. All the decorations were imitations of what they could never be. There was no mistaking it: The Hall of Tranquility was nothing more than a brothel with a sinking reputation.

“My mother is a very important American,” I said to the madam. “If you do not let me go this instant, she will have you convicted in an American court of law and your house will be closed forever.”

“Yes, we know all about your mother. Lulu Mimi. Such an important woman.”

The madam beckoned the six courtesans to come meet me. They were dressed in bright pink and green colors, as if it were still Spring Festival. Four of them looked to be seventeen or eighteen, and the other two were much older, at least twenty-five. A maid, no more than ten, brought steaming towels and a bowl of rose water. I knocked them away and the porcelain smashed onto the tile with the bright sound of a thousand tiny bells. While picking up the slivers, the frightened maid apologized to the madam, and the old woman said nothing that would assure her that the damage was not her fault. An older maid gave me a bowl of osmanthus tea. Although I was thirsty, I took the bowl and threw it at the banners with my name. Black tears ran down from the smeared characters.

The madam gave me an indulgent smile. “Ayo! Such a temper.”

She motioned to the courtesans, and, one by one, they and their attendants politely thanked me for coming and adding prestige to the house. They did not appear genuinely welcoming. When the madam took my elbow to guide me toward a table, I yanked back my arm. “Don’t touch me.”

“Shh-shh,” the madam soothed. “Soon you will be more at ease here. Call me Mother and I’ll treat you just like a daughter.”

“Cheap whore!”

Her smile disappeared and she turned her attention to ten plates with special delicacies that had been set on a tea table. “We’ll nourish you for years to come,” she said, and blathered on with other insincere words.

I saw little meat buns and decided I would spare the food from being destroyed. A maid poured wine into a little cup and set it on the table. I picked up the chopsticks and reached for a bun. The madam tapped her chopsticks on top of mine and shook her head. “You must drink the wine before eating. It is custom.”

I quickly swallowed the foul liquid, then reached again for a bun. With two claps and a wave of her hand, she wordlessly signaled that the food be taken away. I thought she intended that I eat in another room.

She turned to me and said, still smiling, “I’ve made a hefty investment in you. Will you work hard to be worth the burden of feeding you?”

I scowled, and before I could call her foul names, she delivered a fisted blow to the side of my head next to my ear. The force of it nearly snapped my head off my neck. My eyes watered and my ears rang. I had never been struck before.

The woman’s face was contorted and her shouts were faint, distant. She had deafened one ear. She slapped my face and more stinging tears rose. “Do you understand?” she said in her faraway voice. I could not gather my senses long enough to answer before more slaps followed. I threw myself at her and would have pummeled her face if the arms of the menservants had not pulled me away.

The woman slapped me again and again, cursing. She grabbed my hair and yanked back my head.

“You brat, I’ll beat that temper out of you even after you’re dead.”

She then let go and shoved me so hard I lost my balance, fell to the floor, and into a deep dark place.

I AWOKE IN a strange bed with a quilt on top of me. A woman hurried toward me. Fearing it was the madam, I wrapped my arms around my head.

“Awake at last,” she said. “Vivi, don’t you remember your old friend?” How did she know my name? I unlocked my arms and opened my eyes. She had a round face, large eyes, and the questioning look of one raised eyebrow.

“Magic Cloud!” I cried. She was the Cloud Beauty who had tolerated my antics when I was a child. She had come back to help me.

“My name is now Magic Gourd,” she said. “I’m a courtesan here.” Her face looked tired, her skin was dull. She had aged a great deal in those seven years.

“You have to help me,” I said in a rush. “My mother is waiting for me at the harbor. The boat is leaving at five o’clock, and if I’m not there, it will sail away without us.”

She frowned. “No words of happiness for our reunion? You’re still a spoiled child, only now your arms and legs are longer.”

Why was she criticizing my manners at a time like this? “I need to go to the harbor right away or—”

“The boat has left,” she said. “Mother Ma put a sleeping potion in your wine. You have been asleep most of the day.”

I was stunned. I pictured my mother with her new trunks stacked on the dock. The tickets had gone to waste. She would be furious when she learned how cleverly Fairweather had tricked her with his greasy words of love. It served her right for being in such a rush to see her son in San Francisco.

“You must go to the harbor,” I said to Magic Gourd, “and tell my mother where I am.”

“Oyo! I am not your servant. Anyway, she is not there. She is on the boat and it is already sailing to San Francisco. It cannot turn back.”

“That’s not true! She would never leave me. She promised.”

“A messenger told her you had already boarded and that Fairweather was looking for you.”

“What messenger? Cracked Egg? He did not see me go in or out of the consulate.” To everything Magic Gourd said, I countered senselessly, “She promised. She would not lie.” The more I said this, the less sure I was.

“Will you take me back to Hidden Jade Path?”

“Little Vivi, what has happened is worse than you think. Mother Ma paid too many Mexican dollars to the Green Gang to leave even the smallest crack for you to slip through. And the Green Gang made threats to everyone at Hidden Jade Path. If the Cloud Beauties help you, they would be disfigured. They threatened to cut all of Cracked Egg’s leg muscles and leave him in the streets to be run over by horses. They told Golden Dove the house would be bombed and that you would suffer the loss of your eyes and ears.”

“Green Gang? They had nothing to do with this.”

“Fairweather made a deal with them in exchange for settling his gambling debt. He got your mother to leave so they could take over her house without interference from the American Consulate.”

“Take me to the police.”

“How naive you are. The chief of the Shanghai Police is a Green Gang member. They know about your situation. They would kill me in the most painful way possible if I took you away from here.”

“I don’t care,” I cried. “You have to help me.”

Magic Gourd stared at me openmouthed. “You don’t care if I’m tortured and killed? What kind of girl did you grow up to be? So selfish!” She left the room.

I was ashamed. She had once been my only friend. I could not explain to her that I was scared. I had never shown fear or weakness to anyone. I was used to having any predicament solved immediately by my mother. I wanted to pour out to Magic Gourd all that I felt—that my mother had not worried enough for me, and instead she became stupid and believed that liar. She always did, because she loved him more than she loved me. Was she with him on that ship? Would she return? She had promised.

I looked around at my prison. The room was small. All the furniture was of poor quality and worn beyond repair. What kind of men were the customers of this house? I tallied all the faults of the room so I could tell my mother how much I had suffered. The mat was thin and lumpy. The curtains that enclosed the frame were faded and stained. The tea table had a crooked leg and its top had water stains and burn marks, making it suitable only for firewood. The crackle-glazed vase had a real crack. The ceiling had missing plaster and the lamps on the walls were crooked. The rug was orange and dark blue wool woven with the usual symbols of the scholar, and half of them were worn bare or eaten by moths. The Western armchairs were rickety and the cloth was frayed at the edge of the seats. A lump grew in my throat. Was she really on the boat? Was she worried sick?

I was still wearing the hated blue-and-white sailor blouse and skirt, “evidence of my American patriotism,” Fairweather had said. That evil man was making me suffer because I hated him.

At the back of the wardrobe, I spied a tiny pair of embroidered shoes, so worn there was more grimy lining than pink and blue silk. The backs of the shoes were crushed flat. They had been made for small feet. The girl who wore them must have wedged her toes in and walked on tiptoe to give the effect of bound feet. Did she rest her heels on the backs of the shoes when no one was looking? Why had the girl left the shoes behind instead of throwing them away? They were beyond repair. I pictured her, a sad-faced girl with large feet, thin hair, and a gray complexion, worn down like those shoes, a girl who was about to be thrown away because she was no longer of any use. I felt sick to my stomach. The shoes had been placed there as an omen. I would become that girl. The madam would never let me leave. I opened the window and threw them out into the alley. I heard a shriek and looked down. A ragamuffin rubbed her head, then grabbed and clutched them to her chest. She stared at me, as if guilty, then ran off like a thief.

I tried to recall if Mother had worn a guilty expression as I was leaving her side. If so, that would be proof she had agreed to Fairweather’s plan. When I had threatened to stay in Shanghai with Carlotta, she might have used that as an excuse to leave. She might have said to herself that I preferred to stay. I tried to remember other fragments of conversations, other threats I had made, promises she had given, and protests I shouted when she disappointed me. In those pieces was the reason I was here.

I spied my valise next to the wardrobe. The contents would reveal her intentions. If they were clothes for my new life, I would know she had abandoned me. If the clothes were hers, I would know she had been tricked. I slipped over my neck the silvery chain with the key to the valise. I held my breath. I expelled it with gratitude when I saw a bottle of Mother’s precious Himalayan rose oil perfume. I petted her fox stole. Underneath that was her favorite dress, a lilac-colored one she had worn on a visit to the Shanghai Club, where she had boldly strolled in and seated herself at the table of a man who was too rich and important to be told that women were not allowed. I hung this impertinent dress on the wardrobe door and placed a pair of her high-heeled shoes below. It gave the eerie appearance that she was a headless ghost. Below that was a mother-of-pearl box with my jewelry: two charm bracelets, a gold locket, and an amethyst necklace and ring. I opened another small box, which contained lumps of amber, the gift I had rejected on my eighth birthday. I lifted out two scrolls, one short, the other long. I unwound the cloth wrapper. They were not scrolls after all, but oil paintings on canvas. I put the larger one on the floor.

It was the portrait of Mother when she was young, the painting I had found just after my eighth birthday, when I rifled her room for a letter she had just received that had upset her so. I had had only enough time for a glimpse before putting it back. Now, while examining it closely, I felt a peculiar discomfort, as if I were staring at a terrible secret about her that was dangerous for me to know—or perhaps it was a secret about me. Mother’s head was tilted back, revealing her nostrils. Her mouth was closed, unsmiling. It was as if someone had given her a dare and she had taken it without hesitation. Although, perhaps she was also frightened that she had done so and was trying to hide it. Her eyes were wide open and her pupils were so large they turned her green eyes black. It was the stare of a fearful cat. This was who she was before she had learned to disguise her feelings with a show of confidence. Who was the painter enjoying her state of fright?

The painting was similar in style to that of European portraits commissioned as novelties by rich Shanghainese, who had to have the latest luxury that the foreigners enjoyed, even if they were renderings of other people’s ancestors in powdered wigs and their beribboned children with spaniels and hares. They were popular decorations in the salons of hotels and first-class flower houses. Mother had mocked those paintings as poorly executed pretensions. “A portrait,” she had said, “should be that of a person who was breathing at the time it was painted. It should capture one of those breaths.”

She had held her breath when this portrait was done. The longer I looked at her face, the more I saw, and the more I saw, the more contradictory she became. I saw bravery, then fear. I recognized in it something vague about her nature, and I could see she had already possessed it when she was a girl. And then I knew what that was: her haughtiness in thinking she was better than others and smarter than them as well. She believed she was never wrong. The more others disapproved of her, the more she showed her disapproval of them. We ran into all sorts of disapproving people while walking in the park. They recognized her, “The White Madam.” Mother would give them a slow appraisal head to toe, then a sniff in disgust, which always sent me into near fits of giggles as the recipient of her stares and rebukes came undone and retreated speechless.

Usually she gave no further thought to people who had insulted her. But the day she received the latest letter from Lu Shing, she had a festering anger. “Do you know what morals are, Violet? They’re other people’s rules. Do you know what a conscience is? Freedom to use your own intelligence to determine what is right or wrong. You possess that freedom and no one can remove it from you. Whenever others disapprove of you, you must disregard them and be the only one to judge your own decisions and actions …” On and on she went, as if an old wound still festered and she had to cleanse it with venom.

I looked hard at the painting. What conscience did she have? Her right and wrong were guided by selfishness, doing what was best for her. “Poor Violet,” I imagined her saying. “She would be taunted in San Francisco as a child of questionable race. Much better that she stay in Shanghai where she can live happily with Carlotta.” I became incensed. She had always found a way to defend her decisions, no matter how wrong. When a courtesan was forced to leave Hidden Jade Path, she said it was a matter of necessity. When she could not have supper with me, she would tell me it was a matter of necessity. Her time with Fairweather had always been a matter of necessity.

A matter of necessity. That was what she said to suit her own purposes. It was an excuse to be selfish. I recalled a time when I had felt sickened by her lack of conscience. It happened three years ago, on a day that was memorable because it was strange in so many ways. We were with Fairweather at the Shanghai Race Club to watch a Frenchman fly his plane over the track. The seats were filled. No one had ever seen an airplane in flight, let alone right above their heads, and when it soared up, the crowd murmured in unison. I believed it was magic. How else could you explain it? I watched the plane glide and dip, then tilt from side to side. One wing fell off, then another. I thought this was meant to happen, until the plane flew into the center of the racetrack and cracked into pieces. Dark smoke rose, people screamed, and when the mangled aviator was dragged from the wreckage, a few men and women fainted. I nearly vomited. The words dead, dead, dead echoed through the stands. The debris was hauled away, and fresh dirt was poured over the blood. A short while later, the horses entered the track and the races began. I could hear the departing people angrily say that it was immoral to continue the races and shameful that anyone would enjoy them. I thought we would also be leaving. Who could stay, having just seen a man killed? I was shocked that my mother and Fairweather had remained in their seats. As the horses pounded the track, my mother and Fairweather cheered, and I stared at the moist dirt that had been poured to hide the blood. Mother saw no wrong in our watching the race. I had no choice but to be there, and yet I felt guilty, thinking I should have told them what I thought.

Later that afternoon, as we walked back to the house, a little Chinese girl, who might have been around my age, ran out of a dark doorway, and claimed to Fairweather with her smattering of English words that she was a virgin and had three holes for a dollar. The slave girls were a pitiful lot. They had to take at least twenty men a day or risk being beaten to death. What more could we give them besides pity? And even that was difficult to do because there were so many of them. They darted about like nervous chickens, tugging on coats, beseeching men, to the point of being a nuisance. We had to walk briskly past them without giving them a glance. That day, my mother reacted differently. Once we were past the girl, she muttered, “The bastard who sold her should have his little cock cut off with the guillotine for a cigar.”

Fairweather laughed. “You, my dear, have bought girls from those who sold them.”

“There’s a difference between selling a girl and buying her,” she said.

“It’s the same result,” Fairweather said. “The girl becomes a prostitute. It is a collusion of seller and buyer.”

“It’s far better that I buy a girl and take her to my house than for her to wind up as a slave like this one, dead at fifteen.”

“To judge by the flowers in your house, only the pretty ones are worth saving.”

She stopped walking. The remark had clearly riled her. “That is not a reflection of my conscience. It is pragmatism. I am a businesswoman, not a missionary running an orphanage. What I do is a matter of necessity based on the circumstances at hand. And only I know what those are.”

There were those words again: a matter of necessity. Right after she said them, she abruptly turned around and went to the doorway where the girl’s owner sat. She gave the woman some money, then took the girl’s hand and rejoined us. The girl was petrified. She glanced back at her former owner. “At least her eyes don’t have the deadened gaze that most slave girls have.”

“So you’ve just bought yourself a little courtesan,” Fairweather said. “One more saved from the streets. Good on you.”

My mother snapped, “This girl won’t be a courtesan. I have no need of one, and even if I did, she’d never be suitable. She’s already ruined, deflowered a thousand times. She would simply lie on her back with a beaten look of submission. I’m taking her as a maid. One of the maids is marrying and going to her husband’s village.” I learned later that no maid was leaving. I thought for a moment that she had taken the girl because she had a good heart. But then I realized it was her arrogance in showing up anyone who had disapproved of her. She had stayed at the race club for that reason. She bought the girl because Fairweather had made fun of her conscience.

I scrutinized again the oil painting, noting every brushstroke that had created her young face. Had she possessed more sympathy for people when she was my age? Had she felt any for the dead pilot or the little slave girl? She was contradictory, and her so-called matters of necessity made no sense. She could be loyal or disloyal, a good mother, then a bad one. She might have loved me at times, but her love was not constant. When did she last prove that she loved me? I thought it was when she promised not to leave me.

On the back of the painting were these words: “For Miss Lucretia Minturn, on the occasion of her 17th birthday.” I did not know my mother’s birthday or her age. We had never celebrated them and there was never any reason to know. I was fourteen, and if she had given birth to me when she was seventeen, that would make her thirty-one now.

Lucretia. That was the name on the envelope of Lu Shing’s letter. The words below the dedication had been lashed to oblivion by the dark lead of a pencil. I turned the painting faceup and found the initials “L.S.” at the bottom right corner. Lu Shing was the painter. I was certain of that.

I unrolled the smaller painting. The initials “L.S.” appeared on the bottom of that one as well. It was a landscape of a valley, viewed from the edge of a cliff, facing the scene below. The mountain ridges on each side were ragged, and their shadow silhouettes lay on the valley floor. The pendulous clouds were the shade of an old bruise. The upper halves were pink, and the clouds receding in the background were haloed in gold, and at the far end of the valley, an opening between two mountains glowed like the entrance to paradise. It looked like dawn. Or was it dusk? I could not tell whether the rain was coming, or the sky was clearing, whether it was about arriving there with joy or leaving it with relief. Was the painting meant to depict a feeling of hope or was it hopelessness? Were you supposed to be standing on the cliff charged with bravery or trembling in dread of what awaited you? Or maybe the painting was about the fool who had chased after a dream and was looking at the devil’s pot of gold that lay in that glimmering place just beyond reach. The painting reminded me of those illusions that changed as you turned them upside down or sideways, transforming a bearded man into a tree. You could not see the painting both ways at the same time. You had to choose which one it was originally meant to be. How would you know which was right unless you were the one who had painted it?

The painting gave me a queasy feeling. It was an omen, like the worn slippers. I was meant to find it. What happened next was salvation or doom. I felt certain now that the painting meant you were walking into the valley, not leaving it. The rain was coming. It was dusk, turning dark, and you would no longer be able to find your way back.

With shaky hands, I turned the painting over. The Valley of Amazement it said, and below that were initials: “For L.M. from L.S.” The date was smeared. I could make out that it was either “1897” or “1899.” I had been born in 1898. Had Mother received this one along with her portrait? What was she doing before I was born? What was she doing the year after? If Lu Shing had painted this in 1899, he would have still been with my mother when I was a year old.

I threw both paintings across the room. A second later, I was overcome with fright that some part of me would be thrown away and destroyed, and I would never know what it was. She hated Lu Shing for leaving her, so there must have been a very strong reason she had kept the paintings. I ran to claim back the paintings. I cried as I rolled them up, then shoved them into the bottom of the valise.

Magic Gourd walked in. She threw two cotton pajama suits on a chair—loose jackets and pantalets, green with pink piping—the clothes worn by small children. “Mother Ma figured these clothes would keep you from trying to escape. She said you are too vain to be seen in public dressed like a Chinese maid. If you keep your haughty Western ways, she’ll beat you worse than what you already received. If you follow her rules, you’ll suffer less. It’s up to you how much pain you want to endure.”

“My mother is coming for me,” I declared. “I won’t have to stay here much longer.”

“If she does, it won’t be soon. It takes a month to go from Shanghai to San Francisco and another month to come back. If you’re stubborn, you’ll be dead before two months pass. Just go along with whatever the madam says. Pretend to learn whatever she teaches you. You won’t die from doing that. She bought you as a virgin courtesan and your defloration won’t happen for at least another year. You can plot your escape in between times.”

“I’m not a virgin courtesan.”

“Don’t let pride make you stupid,” she said. “You’re lucky she isn’t making you work right away.” She went to my valise and dipped her hands inside and pulled out the fox stole with its dangling paws.

“Don’t touch my belongings.”

“We need to work quickly, Violet. The madam is going to take what she wants. When she paid for you, she paid for everything that belongs to you. Whatever she does not want she will sell—including you, if you don’t behave. Hurry now. Take only the most precious. If you take too many things, she’ll know what you’ve done.”

I refused to budge. Look what Mother’s selfishness had done. I was a virgin courtesan. Why would I want to cling to her belongings?

“Well, if you don’t want anything,” Magic Gourd said, “I’ll take a few things for myself.” She plucked the lilac dress hanging in the wardrobe. I stifled a shout. She folded it and tucked it under her jacket. She opened the box with the pieces of amber. “These aren’t good quality, misshapen in a dozen ways. And they are dirty inside—aiya!—insects. Why did she want to keep these? Americans are so strange.”

She pulled out another package, wrapped in paper. It was a little sailor suit, a white and blue shirt and pantalets, as well as a hat, like those worn by American sailors. She must have bought those for Teddy when he was a baby and was planning to show them to him as proof of her enduring love. Magic Gourd put the sailor suit back into the valise. Madam had a grandson, she said. She picked up the fox wrap with its dangling baby paws. She gave it a wistful look and dropped it back in. From the jewelry box, she removed only a necklace with a gold locket. I took it from her, opened it, and peeled out the tiny photographs on each side, one of Mother, one of me.

And then she fished in deeper and pulled out the two paintings. She unrolled the one of my mother and laughed. “So naughty!” She laid out the one with the gloomy landscape. “So realistic. I have never seen a sunset this beautiful.” She put the paintings in her pile.

As I dressed, she recited the names of the courtesans. Spring Bud, Spring Leaf, Petal, Camellia, and Kumquat. “You don’t have to remember their names for now. Just call them your flower sisters. You’ll know them soon enough by their natures.” She chattered on. “Spring Leaf and Spring Bud are sisters. One is smart and one is foolish. Both are kind in their hearts, but one is sad and does not like men. I will leave it to you to guess which is which. Petal pretends to be nice, but she is sneaky and does anything to be Madam’s favorite. Camellia is very smart. She can read and write. She spends a little money every month to buy a novel or more paper for writing her poems. She has audacity in her ink brush. I like her because she’s very honest. Kumquat is a classical beauty with a peach-shaped face. She is also like a child who reaches for what she wants without thinking. Five years ago, when she was with a first-class house, she took a lover and her earnings dwindled to nothing. It’s the usual story among us.”

“That was the reason you had to leave, wasn’t it?” I said. “You had a lover.”

She huffed. “You heard that?” She fell silent, and her eyes grew dreamy. “I had many lovers over the years—sometimes when I had patrons, sometimes when I did not. I gave too much money to one. But my last lover did not cheat me out of money. He loved me with a true heart.” She looked at me. “You know him. Pan the Poet.”

I felt a cool breeze over my skin and shivered.

“Gossip reached my patron that I had sad sex with a ghost and that he was stuck in my body. My patron no longer wanted to touch me and asked for his contract money back. Puffy Cloud spread that rumor. That girl has something wrong with her heart. In every house, there is one like her.”

“Did you really have the Poet Ghost in your body?”

“What a stupid thing to ask! We did not have sex. How could we? He was a ghost. We shared only our spirit, and it was more than enough. Many girls in this business never experience true love. They take lovers and patrons, hoping they will become concubines so they can be called Second Wife, Third Wife, even Tenth Wife, if they are desperate. But that is not love. It is searching for a change of luck. With Pan the Poet, I felt only love, and he felt the same for me. We had nothing to gain from each other. That was how we knew it was true. When I left Hidden Jade Path, he had to remain because he was part of the house. Without him, I felt no life in me. I wanted to kill myself to be with him … You think I’m crazy. I can see it in your face. Hnh. Little Miss Educated American. You don’t know anything. Get dressed now. If you’re late, Madam will poke another nostril into your face.” She held up the pajamas. “Madam wants all the girls to call her Mother. Mother Ma. They are just sounds without true meaning. Say it over and over again until you can swallow them without choking. Mother Ma, Mother Ma. Behind her back, we call her the old bustard.” Magic Gourd imitated a big squawking bird flapping its wings and swooping around to guard her flock. And then she announced: “Mother Ma did not like your name Vivi. She said it made no sense. To her, it was just two sounds. I suggested she use the Chinese word for the violet flower.”

She pronounced the word for “violet” as zizi, like the sound of a mosquito. Zzzzzz! Zzzzz!

“It’s just a word,” she said. “It’s better that they call you that. You are not that person. You can have a secret name that belongs to you—your American nickname, Vivi, or the flower name your mother called you. My courtesan name is Magic Gourd, but in my heart I am Golden Treasure. I gave that name to myself.”

At breakfast, I did as Magic Gourd had advised. “Good morning, Mother Ma. Good morning, flower sisters.”

The old bustard was pleased to see me in my new clothes. “You see, fate changes when you change your clothes.” She used her fingers like tongs to turn my face right and then left. It sickened me to be touched by her. Her fingers were cold and gray, like those of a corpse. “I knew a girl from Harbin who had your coloring,” she said. “Same eyes. She had Manchu blood. In the old days, those Manchus were like dogs who raped any girl—Russian, Japanese, Korean, green-eyed, blue-eyed, brown-eyed, yellow or red hair, big or tiny—whatever was in grabbing distance as they raced by on their ponies. I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a pack of ponies that are half-Manchu.” She grasped my face again. “Whoever your father was, he had the Manchu bloodlines in him, that’s for certain. I can see it in your jaw and the longer Mongolian taper of the eyes, and also their green color. I heard that one of the concubines to Emperor Qianlong had green eyes. We’ll say you’re a descendant of hers.”

The table was set with savory, sweet, and spicy dishes—bamboo shoots and honeyed lotus root, pickled radishes, and smoked fish—so many tasty things. I was hungry but ate sparingly and with the delicate manners I had seen courtesans use at Hidden Jade Path. I wanted to show her she had nothing to teach me. I picked up a tiny peanut with my ivory chopsticks, put it to my lips and set it on my tongue, as if it were a pearl being placed on a brocade pillow.

“Your upbringing shows,” the old bustard said. “A year from now, when you make your debut, you can charm men to near insanity. What do you say to that?”

“Thank you, Mother Ma.”

“You see,” she said to the others with a pleased smile. “Now she obeys.” When Mother Ma picked up her chopsticks, I had a closer look at her fingers. They resembled rotting bananas. I watched her peck at the remaining bits of food on her plate. The sneaky courtesan Petal stood up and quickly served the madam more bamboo shoots and fish, but did not touch the last of the honeyed lotus root. She waited until Spring Bud helped herself to the last big piece, then said in a chiding tone, “Give that to Mother. You know how much she loves sweets.” She made a show of shoving her own lotus root pieces onto Madam Ma’s plate. The madam praised Petal for treating her like a true mother. Spring Bud showed no expression and looked at no one. Magic Gourd looked sideways at me and whispered, “She’s furious.”

When Mother Ma rose from her chair, she wobbled, and Petal ran to steady her. The madam crossly swatted her away with her fan. “I’m not a feeble old woman. It’s just my feet. These shoes are too tight. Ask the shoemaker to come.” She lifted her skirt. Her ankles were gray and swollen. I guessed her feet under her bindings were even worse.

As soon as the madam left the table, Camellia said to Magic Gourd in an overly polite tone, “My Peer, I cannot help saying that the peach color of your new jacket flatters your coloring. A new client would think you’re at least ten years younger.”

Magic Gourd cursed her. Camellia smirked and walked away.

“We tease each other all the time like that,” Magic Gourd said. “I flatter her thin hair. She flatters my complexion. We laugh rather than cry about our age. The years go by.” I was tempted to tell Magic Gourd that the peach color did not flatter her at all. An older woman wearing a younger woman’s colors only looks as old as she is pretending not to be.

I followed Magic Gourd’s advice. I did what the madam expected. I performed the toady greetings, answered politely when she talked to me. I showed the rituals of respect to the flower sisters. How easy it was to be insincere. Early on, I received a few slaps whenever I had facial expressions that Mother Ma judged to be American. I did not know what they were until I felt the blows and she threatened to grind down any part of me that reminded her of foreigners. When I stared at her as she scolded me, she slapped me for that as well. I learned that the expression she wanted was cowering respect.

One morning, after I had been at the Hall of Tranquility for nearly a month, Magic Gourd told me that I would be moving into a new room in a few days. The old one was meant to humble me. It was a place to store old furniture. “You’ll have my boudoir,” she said. “It’s almost as nice as the one I had at Hidden Jade Path. I’m moving somewhere else.”

I knew what this meant. She was leaving for someplace worse. I would have no ally if she did. “We’ll share the room,” I said.

“How can I do my wooing when you’re in the room playing with dolls? Oh, don’t worry about me. I have a friend in the Japanese Concession. We’re renting a two-story shikumen and will run an opium flower house, the two of us, with no madam to take the profits and charge us for every little plate of food …”

She was going to lower herself to an ordinary prostitute. They would simply smoke a few pipes and then she would lie down and prop open her legs to men like Cracked Egg.

Magic Gourd frowned, knowing what I was thinking. “Don’t you dare pity me. I’m not ashamed. Why should I be?”

“It’s the Japanese Concession,” I said.

“What’s wrong with that?”

“They hate Chinese people there.”

“Who told you that?”

“My mother. That’s why she didn’t let Japanese customers into her house.”

“She didn’t allow them because she knew they’d take away the best business opportunities. If people hate them, it’s because they envy their success. But what does any of that matter to me? My friend told me they’re no worse than other foreigners, and they’re scared to death of the syphilitic pox. They inspect everyone, even at first-class houses. Can you imagine?”

Three days later, Magic Gourd was gone—but for only three hours. She returned and dropped a gift at my feet, which landed with a familiar soft thump. It was Carlotta. I instantly burst into tears and grabbed her, nearly crushing her in my hug.

“What? No thanks to me?” Magic Gourd said. I apologized and declared her a true friend, a kind heart, a secret immortal. “Enough, enough.”

“I’ll have to find some way to hide her,” I said.

“Ha! When Madam finds out I brought her here, I wouldn’t be surprised if she hangs red banners over the door and sets off a hundred rounds of firecrackers to welcome this goddess of war. Two nights ago, I let some rats loose in the old bustard’s room. Did you hear her shouts? One of the servants thought her room was on fire and ran to get the brigade. I pretended to be shocked when I heard the reason for her screams. I told her: ‘Too bad we don’t have a cat. Violet used to have one, a fierce little hunter, but the woman who’s now the madam at Hidden Jade Path won’t give her up.’ The old bustard sent me off immediately to tell Golden Dove that she paid for you and everything you own, including the cat.”

Golden Dove had been glad to relinquish the beast, Magic Gourd reported, and Little Ocean cried copious tears, proof she had treated Carlotta well. But Magic Gourd brought back more than Carlotta. She had news about Fairweather and my mother.

“He had a gambling habit, a fondness for opium, and a mountain of debt. That was not surprising. He took money that people had invested in his companies and used it to gamble, thinking he could then make up for his previous business losses. As his debts piled up, he reported to his investors that the factory had suffered from a typhoon or fire, or that a warlord had taken over the factories. He always had an answer like that, and he sometimes used the same excuse for different companies. He did not know that the investor of one of his companies was a member of the Green Gang, and the investor of another was also with the Green Gang. They learned how many typhoons had happened in the last year. It is one thing to swindle a gangster and another to make fools of them. They were going to hang him upside down and dip his head in coals. But he told them he had a way to pay them back—by chasing away the American madam of Hidden Jade Path.

“Ai-ya. How can a woman so smart become so foolish? It is a weakness in many people—even the richest, the most powerful, and the most respected. They risk everything for the body’s desire and the belief they are the most special of all people on earth because a liar tells them so.

“Once your mother was gone, the Green Gang printed up a fake deed that said your mother had sold Hidden Jade Path to a man who was also a gang member. They recorded the deed with an authority in the International Settlement, one who was also part of the gang. What could Golden Dove do? She could not go to the American Consulate for him. She had no deed with her name on it because your mother was going to mail it after she reached San Francisco. One of the courtesans told Golden Dove that Puffy Cloud had bragged that she and Fairweather were now rich. Fairweather had exchanged the steamer tickets to San Francisco for two first-class steamer tickets to Hong Kong. They were going to present themselves as Shanghai socialites, who had come to Hong Kong to invest in new companies on behalf of Western movie stars!

“Golden Dove was so angry when she told me this. Oyo! I thought her eyes would explode—and they did, with tears. She said that a new gang with the Triad did not care about the standards of a first-class house. They own a syndicate with a dozen houses that provide high profits at low costs. There is no longer any leisurely wooing for our beauties, and no baubles, only money. The Cloud Beauties would have left, but the gangsters gave them extra sweet money to stay, and now they are caught in a trap of debt. The gangsters made Cracked Egg a common manservant, and now the customers who come are swaggering petty officials and the newly rich of insignificant businesses. These men are privy to the attentions of the same girls once courted only by those far more important. There is no quicker way to throw away the reputation of a house than to allow the underlings to share the same vaginas as their bosses. Water flows to the lowest ditch.”

“They have no right,” I said over and over again.

“Only Americans think they have rights,” Magic Gourd said. “What laws of heaven give you more rights and allow you to keep them? They are words on paper written by men who make them up and claim them. One day they can blow away, just like that.”

She took my hands. “Violet, I must tell you about pieces of paper that blew back and forth between here and San Francisco. Someone sent a letter to your mother claiming it was from the American Consulate. It said you had died in an accident—run over in the road or something. They included a death certificate stamped with seals. It had your real name on there, not the one Fairweather was going to give you. Your mother sent a cable to Golden Dove to ask if this was true. And Golden Dove had to decide whether to tell your mother the death certificate was fake, or to keep the beauties, you, and herself from being tortured, maimed, or even killed. There was really no choice.”

Magic Gourd removed a letter from her sleeve and I read it without breathing. It was from Mother. The letter rambled on about her feelings in getting the letter, her disbelief, her agony in waiting to hear from Golden Dove.

I’m tormented by the thought that Violet might have believed before she died that I had left her behind deliberately. To think those unhappy thoughts might have been her last!

I seethed. She chose to believe I was on board because she was eager to sail away to her new life with Teddy and Lu Shing. I asked Magic Gourd for paper so I could write a letter in return. I would tell Mother I wasn’t fooled by her lies and false grief. Magic Gourd told me no letter from me would ever leave Shanghai. No cable could be sent. The gangsters would make sure of that. That’s why the letter Golden Dove wrote to my mother had been the lies they told her to write.

I BECAME A different girl, a lost girl without a mother. I was neither American nor Chinese. I was not Violet nor Vivi nor Zizi. I now lived in an invisible place made of my own dwindling breath, and because no one else could see it, they could not yank me out of it.

How long did my mother stand at the back of the boat? Was it cold on deck? Did she miss the fox wrap she put in my valise? Did she wait until her skin prickled before she went inside? How long did she take to choose a dress for the first dinner at sea? Was it the tulle and lace? How long did she wait in the cabin before she knew no knock would come to her door? How long did she lie awake staring into the pitch-dark? Did she see my face there? Did she see the worst? Did she wait to watch the sun come up or did she stay in bed past noon? How many days did she despair, realizing each wave was one more wave farther from me? How long did it take for the ship to reach San Francisco, to her home? How long by the fastest route? How long by the slowest route? How long did she wait before Teddy was in her arms? How many nights did she dream of me as she slept in her bedroom with the sunny yellow walls? Was the bed still next to a window that was next to a tree with many limbs? How many birds did she count, knowing that was how many I was supposed to see?

How long would it have taken a boat to return? How long by the fastest route, by the slowest route?

How slowly those days went by as I waited to know which route she took. How long it has been since the slowest boats have all come and have all gone.

THE NEXT DAY, I moved into Magic Gourd’s boudoir. I had kept from crying as she packed up her belongings. She held up my mother’s dress and the two rolled-up paintings and asked if she could take them. I nodded. And then she was gone. The only part of my past that remained was Carlotta.

An hour later, Magic Gourd burst in the room. “I am not leaving, after all,” she announced, “thanks to the old bustard’s black fingers.” She had been concocting a plan for two days and proudly unveiled how it unfolded. Just before she left, she met with Mother Ma in the common room to settle her debts. When Mother Ma started doing calculations on the abacus, Magic Gourd raised the alarm.

“‘Ai-ya! Your fingers!’ I said to her. ‘They’ve grown worse, I see. This is terrible. You don’t deserve this misfortune of health.’ The old bustard held up her hands and said the color was due to the liver pills she took. I told her I was relieved to hear this, because I thought it was due to something else and I was going to tell her to try the mercury treatment. Of course, she knew as well as anyone that mercury is used for syphilis. So she said to me: ‘I’ve never had the pox and don’t you be starting rumors that I do.’

“‘Calm down,’ I said to her. ‘My words jumped out of my mouth too soon and only because of a story I just heard about Persimmon. She once worked in the Hall of Tranquility. That was before my time, about twenty years, but you were already here. One of the customers gave her the pox, and she got rid of the sores, but then they came back, and her fingers turned black, just like yours.’

“Mother Ma said she did not know of any courtesan named Persimmon who had worked in the Hall of Tranquility. Of course, she didn’t. I had made her up. I went on to say she was a maid, not a courtesan, so it was no wonder she would not know her by name. I described her as having a persimmon-shaped face, small eyes, broad nose, small mouth. The old bustard insisted her memory was better than mine. But then the clouds of memory lifted. ‘Was she dark-skinned, a plump girl who spoke with a Fujian accent?’

“‘That’s the one!’ I said and went on to tell her that a customer used to go through the back door to use her services for cheap. She needed the money because her husband was an opium sot and her children were starving. Mother Ma and I grumbled a bit about conniving maids. And then I said Persimmon’s customer was a conniver, too. He called himself Commissioner Li and was the secret lover of one of the courtesans. That got the old bustard to sit up straight. It was an open secret among the old courtesans that the old bustard had taken the commissioner as a lover.

“‘Ah, you remember him?’ I said. She tried to show she was not bothered.

“‘He was an important man,’ she said. ‘Everyone knew him.’

“I poked a bit more. ‘He called himself Commissioner,’ I said. ‘But where did he work?’

“And she said, ‘It had something to do with the foreign banks and he was paid a lot of money to advise them.’

“So I said, ‘That’s strange. He told you and no one else that.’

“Then she said, ‘No, no. He didn’t tell me. I heard it from someone else.’

“I made my face look a little doubtful before going on: ‘I wonder who said that. As the rumors go, everyone thought he was too important to question. One of the old courtesans told me that if he had said he was ten meters tall, everyone would have been too afraid to correct him. He sat at the table with his legs wide apart, like this, and wore a scowl on his face, as if he were the duke of sky and mountains.’ That was the way all important men sit, so of course, she could picture him in her mind.

“The old bustard said, ‘Why would I remember that?’

“I sprang my trap. ‘It turns out he was a fake, not a commissioner at all.’

“‘Wah!’ She jumped out of her chair, and then immediately pretended the news meant nothing to her. ‘An insect just bit my leg,’ she said. ‘That’s why I leapt up.’ To improve the lie, she scratched herself.

“I gave her more to scratch: ‘He never came with friends to host his own parties. Remember that? People were expected to invite him to their parties once he arrived. Such an honor! Everyone wanted to please him. In fact, one of the courtesans was so impressed with his title, she gave her goods away, hoping he would make her Mrs. Commissioner. She took him into her boudoir and she never knew he had already stuck himself into Persimmon just before visiting her.’

“The old bustard’s eyes grew really big when I said that. I was beginning to feel a little sorry for her, but I had to go on. ‘And it is even worse than that,’ I said. I told her what I had heard about Commissioner Li, facts she would clearly remember. ‘Whenever he shared this courtesan’s bed, he told her to go ahead and put a full three-dollar charge on his bill—a charge for a party call, even though he had not held a party. He said he did not want her to lose money from spending so much time with him instead of with other suitors. Anyone would think he was generous beyond belief. By the New Year, he owed nearly two hundred dollars. As you know, it’s customary for all clients of the house to settle their accounts that day. He never did. He was the only one. He never showed his face again. Two hundred dollars’ worth of fucks.’

“I saw the old bustard’s mouth was locked into an expression of bitterness. I think she was trying to keep from cursing him. I said what I knew she was thinking: ‘Men like that should have their cocks shrivel up and fall off.’ She nodded vigorously. I went on. ‘People say that the only gift he gave her was syphilitic sores. They assumed he did, since the maid had it—a sore on her mouth, then her cheek, and who knows how many more in places we couldn’t see.’

“The blood drained from the old bustard’s face. She said, ‘Maybe it was the maid’s husband who gave her syphilis.’

“I was not expecting her to come up with this, so I had to think fast. ‘Everyone knew that the old sot could barely lean over the side of his bed to piss. He was a bag of bones. But what difference did it make whether she had it first or he did? In the end, they both had the pox, and everyone figured he must have given it to the courtesan, and she probably did not even know. Persimmon drank mahuang tea all day long, to no avail. When her nipples dripped pus, she covered them in mercury and got very sick. The sores dried up, and she thought she was cured. Six months ago, her hands turned black, and then she died.’

“The old bustard looked as if a pot had fallen on her head. Really, I felt sorry for her, but I had to be ruthless. I had to save myself. Anyway, I didn’t go on, even though I had thought to say that someone learned that the Commissioner of Lies had died of the same black hand disease. I told her that was the reason I had feared for her when I saw her hands. She mumbled that it was not a disease but the cursed liver pills. I gave her a sympathetic look and said we should ask the doctor to check her chi to get rid of this ailment, since those pills were doing no good. Then I went on: ‘I hope no one believes you have the pox. Lies spread faster than you can catch them. And if people see you touching the beauties with your black fingers, they might say the whole house is contaminated. Then the public health bureaucrats will come, everyone will have to be tested, and the house closed down until they verify we are clean. Who wants that? I don’t want someone examining me and getting a peek for free. And even if you’re clean, those bastards are so corrupt, you’ll have to give them money so they don’t hold up the report.’

“I let this news settle in before I said what I had wanted all along. ‘Mother Ma, it just occurred to me that I might help you keep this rumor from starting. Until you correct the balance in the liver, let me serve as Violet’s teacher and attendant. I’ll teach her all the things I know. As you recall, I was one of the top Ten Beauties in my day.’

“The old bustard fell for it. She nodded weakly. For good measure, I said: ‘You can be sure that if the brat needs a beating, I’ll be quick to do it. Whenever you hear her screaming for mercy, you’ll know that I’m making good progress.’

“What do you think of that, Violet? Clever, eh? All you have to do is stand by the door once or twice a day and shout for forgiveness.”

THERE WAS NO single moment when I accepted that I had become a courtesan. I simply fought less against it. I was like someone in prison who was about to be executed. I no longer threw the clothes given to me on the floor. I wore them without protest. When I received summer jackets and pantalets made of a light silk, I was glad for the cool comfort of them. But I took no pleasure in their color or style. The world was dull. I did not know what was happening outside these walls, whether there were still protestors in the streets, whether all the foreigners had been driven away. I was a kidnapped American girl caught in an adventure story in which the latter chapters had been ripped out.

One day, when it was raining hard, Magic Gourd said to me, “Violet, when you were growing up you pretended to be a courtesan. You flirted with customers, lured your favorites. And now you are saying you never imagined you would be one?”

“I’m an American. American girls do not become courtesans.”

“Your mother was the madam of a first-class courtesan house.”

“She was not a courtesan.”

“How do you know that? All the Chinese madams began as courtesans. How else would they learn the business?”

I was nauseated by the thought. She might have been a courtesan—or worse, an ordinary prostitute on one of the boats in the harbor. She was hardly chaste. She took lovers. “She chose her life,” I said at last. “No one told her what to do.”

“How do you know that she chose to enter this life?”

“Mother never would have allowed anyone to force her to do anything,” I said, then thought: Look what she forced on me.

“Do you look down on those who cannot choose what they do in life?”

“I pity them,” I said. I refused to see myself as part of that pitiful lot. I would escape.

“Do you pity me? Can you respect someone you pity?”

“You protect me and I’m grateful.”

“That’s not respect. Do you think we are equals?”

“You and I are different … by race and the country we belong to. We cannot expect the same in life. So we are not equal.”

“You mean I must hope for less than you do.”

“That is not my doing.”

Suddenly, she turned red in the face. “I am no longer less than you! I am more. I can expect more. You will expect less. Do you know how people will see you from now on? Look at my face and think of it as yours. You and I are no better than actors, opera singers, and acrobats. This is now your life. Fate once made you American. Fate took it away. You are the bastard half who was your father—Han, Manchu, Cantonese, whoever he was. You are a flower that will be plucked over and over again. You are now at the bottom of society.”

“I am an American and no one can change that, even if I am held against my will.”

“Oyo! How terrible for poor Violet. She is the only one whose circumstances changed against her will.” She sat down and continued to make chuffing noises as she threw me disgusted looks. “Against her will … You can’t make me! Oyo! Such suffering she’s had. You’re the same as everyone here, because now you have the same worries. Maybe I should do what I promised Mother Ma and beat you until you learn your place.” She fell silent, and I was grateful that her tirade had ended.

But then she spoke again, now in a soft and sad voice, as if she were a child. She looked away and remembered when her circumstances changed, again and again.