Читать книгу Where the Past Begins: A Writer’s Memoir - Amy Tan - Страница 12

CHAPTER TWO MUSIC AS MUSE

ОглавлениеI’ve never played any of Rachmaninoff’s music on the piano. Had I tried, any one of his pieces would have killed me with its demands for polar-opposite dynamics, acrobatic articulation, and cool concentration while evoking the extremes of human emotions at inhuman speed. While I have always liked music that takes me into dark thoughts, Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique was about as gloomy and as difficult a song as I was able to manage. In comparison, I thought Rachmaninoff’s music was over the top on a psychopathology scale. It sounded like the voice of a hysteric who warbles between pledges of undying love and threats of suicide. Minor struggles become catastrophes, hopes bubble into delusions, and blame turns to vengeance, ending with someone’s ancestral home being burned to the ground. This music would have been ideal for accompanying the moods of my mother.

And then, about fifteen years ago, I fell in love with Rachmaninoff’s music. I found it hard to believe I had ever found fault with it. Age probably had much to do with my changing musical tastes. Over the years, I’ve accumulated plenty to reflect on: chest-ripping joy, strange fortune, disembowelment by betrayal, and love cratered deeper by the loss of far too many, including my mother. Rachmaninoff’s music has become a wonderfully sympathetic companion. My fingers remain still. I am the listener, ready to take the emotional path into a story.

I used to think that everyone saw stories in music. But when I learned this was not true, it was like discovering that people don’t see a story when they read words, that it is only mental understanding. I’m not saying that music should contain story narratives. It’s more that I can’t stop them from emerging freely, which, sad to say, is not what normally happens when I write novels. Writing requires conscious crafting, and the more conscious I am of how I write, the clumsier my sentences come out. The more effort I expend, the less imagination is available. In contrast, when I experience stories in music, it’s effortless—and that’s because I am not composing. I’m simply the listener, and through my imagination I can wander far into a field of sound. The experience is fun, even exhilarating, but I could never use either the process or the output for a novel. My imagination is oblivious to craftsmanship and focus. The story may have holes and inconsistencies. The character may morph several times. The storyline may be chaotic, predictable, or even maudlin. But I can’t improve this spontaneous story any more than I could adjust the weirdness of dreams during sleep. They are simply what my mind went to in the moment—the freely formed melodic reveries guided by the emotions I feel in music.

In recent years, I’ve noticed an increasing need for reverie for some portion of the day. I feel this most acutely when I am on book tour and must talk, answer questions, and be a scintillating conversationalist from morning to night. I reach a point when my mind no longer wants to hear myself talk nor monitor the intelligence or truth of what I’m saying. It wants to take leave of orderly thoughts and the common sense to not mention sex and drugs in front of a general audience with young children. If I ignore the need to silence myself, I eventually feel mentally claustrophobic, as if I’m on a crowded elevator that stops at no floor.

I find reverie in drawing, or sitting in the garden on a sunny day when birds are hopping about. I find reverie in watching fish in an aquarium. And there are also melodic reveries, which are slightly different from other forms. The stories I see in music allow my mind to stretch—much in the same way one might stretch a muscle that is cramped. By allowing my imagination to run with the music, it acts as a purgative in clearing my mind of cluttered thoughts. No matter where I am in the world, music is the bringer of reverie. It is not simply pleasure. It is essential.

I don’t see full stories with every piece of music. If the song is only a page or two, a scene and mood may appear, but when the music stops, the scene will, too. That’s the case with Schumann’s songs in Scenes from Childhood, which I played when I was eleven or so. Now, just as then, the songs evoke a scene, a child, and her moods. “Pleading Child” was a girl pouting and tugging at her mother’s skirt to buy her a doll. “Perfectly Contented” was the same child, dancing with her new doll. I liked the songs well enough, mostly because they were easy to learn, but I did not identify with the conniving child. Only one song from that album felt true to the way I felt: “Traumerei,” which simply means “dreaming” in German. I grew up thinking it meant “trauma,” or “tragedy,” and that the song expressed perpetual heartache. That is still the way I hear “Traumerei.” If “Pleading Child” had been followed by “Traumerei,” I would have imagined not just the girl trying to wangle a doll from her mother but also the transformational event that followed: a mother and father kneeling at the bedside of their recently deceased child, who is now holding her coveted doll, posthumously given. The emotions in “Traumerei” signaled the end of childhood, and at age eleven, when preadolescent hormones were kicking in, that song was perfect for me.

Larger pieces—sonatas, symphonies, fantasias, concertos, and the like—are long enough to carry me into a narrative covering the vicissitudes of life. The stories they evoke are harrowing. They follow bad maps and sudden hairpin turns. Happiness, hard work, and Christian intentions go plummeting off cliffs. These turbulent melodic stories don’t reflect my current life. I’m a fairly happy person. I worry only a bit out of habit, which is why I make lists. I’m prone to petty irritations, like everyone, and only occasionally do I wish I knew voodoo to make certain people wake up mooing like cows. Yet the music I choose for melodic stories are not what I would characterize as happy. They are dramatic and strong enough in emotion to knock loose self-control. The composers whose music provides that emotional range are the “Romantics”—from Beethoven, Shubert, Mendelssohn, and Schumann to Chopin, Mahler, Debussy, Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Rimsky-Korsakov, early Stravinsky, and, of course, Rachmaninoff. The romanticism of their music should not be confused with tunes suitable for marriage proposals. The music I am the most drawn to is more freely driven by the story, and comes with full orchestrations and dynamic extremes, which impart the emotional sweep I love by literally sweeping from one section of the orchestra to another, violins to cellos, to woodwinds, to percussion, and onward. The dark mood in music serves as momentum. You see dark clouds and sense rain may come, and it does, with gale force winds. The narrative moves forward in bad weather. People run for cover to escape lightning. If it’s sunny and people are happy, less happens. People sit down for a picnic, followed by a long nap.

When the music is played with the full orchestra, I experience the story omnisciently. But the point of view is fluid and can switch to a first-person narrator when the melody takes on the voice of a solo instrument. And the instrument I love most is the piano. It can hold the world in two hands and evoke practically anything, from landscapes, battles, and county fairs, to parishioners in a large church or a single penitent praying on calloused knees for love or mercy.

The time period and setting in the story is anchored to the nationality of the composer and the period in which the music was composed. With Rachmaninoff’s music, for example, the story location is what you would find in a folktale in a pre-Bolshevik Russia. My imagination is peevishly stubborn about the time and the parameters of setting. Opera directors are able to relocate nineteenth-century operas into twenty-first-century parking lots and Laundromats, while also freshening up the social or political context. My conscious attempt to change that setting would be as successful as my contriving a novel about a family of athletes in Greenland. Forcing a different context would take me off reverie and into the conscious role of a writer. If I have to push my mind to go in a certain direction that is not intuitive, it can no longer imagine freely. It’s more like a committee throwing out ideas for a whiteboard marketing strategy.

As the listener, I don’t have to work, but I am not passive either. It is similar to what happens when I read. Once the story captures my senses, I am no longer conscious of the act of reading words. I am in the story. So it is with music, except that, unlike reading, the melodic story is not precast. It is suggested by mood. I have found that both stories and music use motifs as recurring patterns that evoke an idea, an emotion, or a memory. The motifs are subtle—unlike the elaborately embroidered symbolism of the scarlet letter that Hester Prynne wears over her heart, or the sled named Rosebud that Citizen Kane calls for on his deathbed. I may not notice elements as motifs when they are mixed in with everything else in a story. It could be a view of six mountains. It could be a single word said by a character. In music, it could be a diatonic passage, a fast tempo, or an echo of the melody played in bass clef. What makes them motifs is not simply that they recur. It has to do with my recognizing where and when they recur, as well as what precedes and what follows them. In a story, the significance of six mountains depends on someone seeing them for the first, second, or third time. The significance of a broken cartwheel depends on having characters who are deterred from reaching their destination. The significance of these motifs is a relationship, singly and together, which grows as I continue to recognize it in all its variations. When I recognize the motifs, what once seemed random or ordinary now has an interesting and possibly deepening pattern, which is also intuitive knowledge. The act of recognizing intuitive knowledge at a particular moment is the epiphany. It’s the whole thing, not the pattern alone. The pattern itself quickly becomes hindsight that is on its way to becoming a homily, e.g., a view of six mountains changes according to how fast you want to go past them. Through subtle change, both fiction and music can reveal what is different and what is connected: disillusionment that becomes reconciliation with the past; altruism that becomes betrayal by necessity. These nuances of emotional truth can be caught in a single line of text or a short passage of notes. I can feel it within a blunt word or the abrupt resolution of a chord.

My tendency to see stories in music was probably influenced by the soundtracks of cartoons I saw as a child. They were scored to correspond to actions in a plot—the xylophone and pizzicato notes on violins matched Wile E. Coyote’s tiptoed steps as he set up a trap for Road Runner. A slide of notes on the bassoon suggested Elmer Fudd had come up with a devious plan to foil Bugs Bunny, and a downward slide of notes on the violin let you know it wasn’t such a good idea after all. During childhood, cartoons were a great way to listen to classical music. They still are. Bugs Bunny plays songs by Liszt and Chopin. Elmer Fudd sings “Kill the Wabbit” to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.” Carl Stallings, who orchestrated all the Loony Tunes cartoons, should get unending credit for introducing generations of kids to classical music. I rank Fantasia as the pinnacle of musical cartoon mastery for creating stories out of the music of different composers, including Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Suite, and Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain. The composers were inspired by a folktale, heroic myth, or poems. In “Night on Bald Mountain,” darkness suffocates a small village and specters of death float up like crematory ashes. Heavy stuff for little kids with eyes wide open to uncensored imagination.

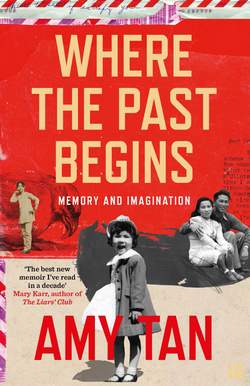

Christmas 1959. In matching pajamas: John, five; Peter, nine; and me, seven.

There was yet another way that music released stories for me. It came from the sheer boredom of practicing the piano one hour a day—the same prelude, rondo, or sonata, and the same mistakes. I had to remain fully attentive to sharps and flats, tempo and tone, pedaling and fingering—all the mind-numbing work that was conducive more to inspiring hatred of music than reverie. The piano was a daily reminder of failure, a fact reinforced by my mother, who called attention to my lack of progress and enthusiasm. I eventually discovered that when emotions accompanied the music, it was much easier to remember the dynamics of the piece. If a story came with the music, it was always about me, whatever happened recently, be it discord in the home or an unrequited crush. I felt angry when playing forte in the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique. I felt unruffled happiness when the music flowed in adagio cantabile. Self-pity always came in crescendo surges, and lonely tears ebbed in diminuendo until there was stillness, silence, and death. The music was mine, both mistakes and emotions.

I had a rare opportunity to see how film scores are composed. During the film adaptation of The Joy Luck Club, I was given the titular role of coproducer, which, I happily discovered, required no meetings but allowed me to tune in to the creation of the music for the different scenes. Early on, the composer, Rachel Portman, sent us one of the motifs that would recur throughout much of the movie, with variations for each scene. The motif was a short phrase of notes on a pentatonic scale, the five-note scale typical of Chinese music. It was the foundation for building the music in the opening, and it was transformed for other scenes. It could change into a darker mood of war, or a lonelier, heartbreaking one of a mother’s grief. It was as if this motif was the heart and voice of one character and the signature moment from her past that revealed the pattern of her life, one she recognized but her daughter did not.

The music for our film had all the characteristics of fin de siècle romanticism: songlike melodies based on emotion, lush orchestrations, and extremes in the dynamics. The tone and melody followed what was happening in each scene, and so closely that the music could alternately serve as subconscious memory or to express what was felt but was more powerful left unsaid. Instead of a mother saying, “I ache for my daughter the way my mother ached for me,” the poignant motif from a scene in the past could express the complications of love, when present and past merged. Whatever had been nearly forgotten could be recalled by one of the motifs. Cue up the violins for the mind-reeling vortex into the past. Or let it simply be silence. We intuit things in so many combinations of our senses, and sometimes we forget silence. In music, silence is deliberate. When I finally heard the completed music Portman had orchestrated for each scene, I was weeping with the opening credits. That was not surprising. I am often brought to tears at the symphony or opera. But in this case, I wasn’t the only one who was visibly moved by Portman’s music. The director and coscreenwriter had the same tearful reactions, and that made us ecstatic. If you can move an audience to tears, they willingly give themselves to you. There is art, purpose, and manipulation in film music.

Because film music is deliberately composed for mood in scenes and characters, I find it ideal accompaniment while writing a novel. It serves both practical and synesthetic purposes. I discovered the former when I was working on my first novel, The Joy Luck Club. The house next to ours was undergoing renovation, and each day, starting at 8:00 A.M., jackhammers would start up, blasting the concrete in a basement just ten feet from where I sat in my basement. Since childhood, I’ve had an impressive ability to tune out my surroundings, much to the annoyance of my parents, and sometimes, my husband. I can be in a crowded room and still read or write, as long as nobody tries to engage me. My ability did not extend to jackhammers. I eventually solved this problem by listening to music through headphones. While I could still hear the noise, I was able to choose the music as foreground, what I paid attention to. The jackhammers became the background. Volume alone did not determine my focus. Over the next few days, I made a serendipitous discovery: Each morning, when I put on the headphones and played the same song, the music transported me not just back to writing but into the scene. My brain had imprinted the music and scene as inseparable. I had stumbled upon a form of self-hypnosis for writing. Over the next few months, I customized the songs to the scenes, and as jackhammers gave way to drilling, then banging, tapping, and sanding, I went from listening to The Firebird suite to selections of what my husband described as New Age gooey music. Those were the precursors to soundtracks.

Music continues to be the best way to keep me seated in the chair and writing. Even so, it still takes me years to write a book. I have many distractions in life, a growing list. I went through a period in which I played brainwave entrainment programs—music combined with binaural tones for brain wave frequencies associated with wakefulness, relaxation, creativity, and dreaming. If I had wanted, I could have customized music tracks and brain wave patterns for “calm reflection,” “anger relief,” “brainstorming,” and even “euphoria.” Imagine it—a human jukebox of moods. But I couldn’t do it. That degree of brain manipulation reminds me of the film Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Individual personality and self-will are replaced with standard-issue outer space aliens.

I still use music to write scenes. I am embarrassed to admit that I actually have playlists titled “Joyful,” “Worried,” “Hopeful,” “Destruction,” “Disaster,” “Sorrow,” “Renewal,” and so forth. I choose one track and play it for however long it takes me to finish the scene. It could be hundreds of times. The music ensures that emotion is a constant, even when I am doing the mental work of crafting the story, revising sentences as I go along. It enables me to return to the emotional dream after my focus has been interrupted by barking dogs, doorbells, or my husband bringing me lunch (what a dear man). Even when no one else is home, I put on headphones. It has the psychological effect of cutting me off from the world. It dampens sensory distractions and emphasizes the aural sense, the one needed for listening to the voice of the story. I take off the headphones when dinner is ready. I put them back on after dinner or the next morning. The emotional mood is still there. The hypnotic effect takes hold: when I hear the violins, I’m back in a cramped, cold room in China. Auditory memory has become the story’s emotional memory.

I’m particularly drawn to film scores composed by Alexandre Desplat and Ennio Morricone, both known for lush orchestrations in the tradition of romanticism. The solos are often poignant and serve as thoughts of an individual character. They do the same for a character I am creating for a novel. While writing The Valley of Amazement, the track “Wong Chia Chi’s Theme,” from Desplat’s score for the film Lust, Caution took me and my narrator seamlessly into the languorous life of a first-class courtesan house. It opens with an ominous tone set by cellos and bass, and then the piano comes in, just the right hand, playing the simple melody. Those are the internal emotions of a woman who is isolated, frightened, and losing resilience. She moves forward into danger, and now two hands play the melody in octaves, recalling a parallel moment from the past. For another scene, I chose the opening theme from Desplat’s score for The Painted Veil to simulate a nervous mood on a long journey to an uncertain future. I listened to “Gabriel’s Oboe” from Morricone’s soundtrack for The Mission as the spiritual complement to exultant relief and joy at the end of the journey. That particular piece was later rerecorded for another album, but instead of the oboe solo, Yo-Yo Ma plays the melody on cello, and his rendition is especially good for expansive emotions related to spiritual revelation, epiphanies, infatuation, and betrayal. A slight change in tempo, key, and bowing technique conveys how falling in love is similar to falling into an abyss.

I’ve become more discerning about my selections over time. One of my favorite pieces fell out of favor when it was used in the film Master and Commander. The movie was quite affecting, so much so that afterward, whenever I heard Ralph Vaughan Williams’s “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis,” I pictured a drowning sailor fruitlessly waving his arms in a stormy sea as a majestic ship sailed away. I cannot write to pop, hip-hop, rap, or rock. They have throbbing beats that do not match contemplative moods. Any song with a singer doesn’t work for me—even if it is the most tragically beautiful of opera arias sung in Italian. I can still see the singer, and he or she does not belong in my story. I would not be able to listen to a gavotte or waltz unless I was writing a scene that includes gavotting or waltzing in a seventeenth-century castle. Although I am a devotee of bebop jazz, I cannot listen to it when I write, not even a piano solo. By its nature, improvisational jazz is unpredictable and wonderfully quirky. I hear its music as a personality with strong opinions. I need to be my own version of quirky when I write. The opinions I hear in my head have to be my own.

My favorite Rachmaninoff piece is the Concerto No. 3 in D minor, the “Rach 3,” as it is known among my friends who are as rapturous about it as I am. It is in my top five. I read that it was Rachmaninoff’s favorite, too, and for reasons I wish I knew. I believe it was written when he was anguished that he could not return to Russia. But what did he want to return to? That’s what is in the music. Did he feel that it was musically more interesting? The melody seizes me by the third measure and becomes emotional circuitry. There are days when I play the concerto on auto-repeat and listen to it all day, even when I am not writing. I love this music so much I have five recordings, including the scratchy one in which Rachmaninoff plays Rachmaninoff, and at such speed I imagine his fingers whipping up winds that blow the audience’s hair askew. His performance of the first movement takes a little over ten minutes, whereas most pianists cover it in about sixteen or seventeen. Was that the tempo he had intended? I read speculation that Rachmaninoff’s large hands, ones that could span thirteen keys, enabled him to play faster, and thus he did. But what musician, let alone composer, allows hand size to serve as the basis for tempo? Another hypothesis pointed to pure commercialism: a 78 rpm record could accommodate no more than a ten-minute performance. Someone else suggested that Rachmaninoff played faster because the derrieres of most average symphony-goers could not remain seated for a full concert played at normal tempo. I prefer to believe that these are apocryphal tales whose origins lie in gripes and rumors spread by conductors and musicians who could not keep pace. I want to believe that what shapes any composition and its performance is a deeper and intuitive sense of beauty and not the lowest common denominator.

The recording of the Concerto No. 3 that I love best is by the London Philharmonia, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, with Yefim Bronfman on piano. I have seen Bronfman play live on the symphony stage. I once nearly leaped out of my chair with an odd feeling of fright and ecstasy, as his fingers tread through low bass notes and then crashed against them. He can also play with astonishing delicacy. In one passage of the Concerto No. 3, I always sense a millisecond of held breath between notes that feels like the missed beat that sends a heart into palpitation.

Yesterday, I listened to the Concerto No. 3 again and took notes by hand on the story I saw. I wanted to understand how my imagination plays freely with music. When the song ended, and I looked at my notes, I saw that the story had many cartoonish and fable-like qualities. But I did not think the character was my familiar. She is unstable, needy, in constant crisis, and exhausting to be around. If my husband has a different opinion, he has yet to tell me. The story bears some similarities to Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary—a female heroine with a fatal flaw when it comes to disregarding everything, including society, for the sake of passion. The character in this story does a lot of internal wailing. I would not want to read that in a novel or hear a real person go on and on like that. But here, the excess is wonderful. There are sudden gaps in the narrative. The male character is nearly nonexistent. If this were judged by the standards of a novel, it would be viewed as overly dramatic, soppy, and a little too easy in what happens at the close of those victorious chords. As private reverie, I found it emotionally whole, a complete story. It was a crazy wild ride and I could actually see a little bit of my younger self in there.

So here is how the story played out. I’ve given a name to the character, Anna, although in my imagination she does not need one because I am the first-person narrator. The approximate times are based on Bronfman’s performance. The comments in brackets denote what I think are the origins of the imagery.

00:00 The orchestra opens with an ominous undercurrent. The piano melody enters soon after, a simple, clean diatonic played in octaves. Anna, a young maiden in a cloak, is alone, trudging up an incline on a countryside road. Today is different, she tells herself. Her life is about to change. She is sure of it. She hopes. She is uncertain. She fears she may be disappointed or rejected. She must resist this nauseating hope. But when she reaches the crest, she sees the town on the other side of an open valley. [In my mind, it looks very much like the Land of Oz on the other side of a vast poppy field.] Her lover is waiting. Anna shrugs off the weight of fear and races forward with such determination she feels as if she is barely touching the road. [I see her walking as Neil Armstrong did on the moon.] She recognizes what has eluded her all her life—the knowledge that there is no greater meaning than to fulfill desire. Buoyed by this realization, her dress fills like a balloon and carries her toward love.

1:00 As Anna draws closer to the town, dark thoughts arrive and confuse her. She thinks about the wretched dark days when she existed with nothing to desire. She pictures in her mind the lonely life she has in a large lifeless house with white walls and tall ceilings. The rooms are nearly empty. Splayed books in white covers lay scattered on the floor. She has read each halfway through before throwing them down in disappointment. They did not tell her the reason she is alive. She has roamed for years from one room to another, calling to God to tell her why she deserves such loneliness, then cursing because she receives no answer. She has no memories of life with others, not even her parents.

2:10 As Anna walks toward her lover, she recalls the moment she knew her life would change. Yesterday, her loneliness had become unbearable, and to avoid succumbing to madness, she flung herself out the door and set on the road with only rage as her compass. A dark forest, a black sea—what did it matter? She was trudging along this same road, hurling invectives to God, when she saw a young man coming from the other direction. They exchanged quick glances, and just as they were about to walk past each other, they both stopped and openly stared at one another. By merely looking into his eyes, she knew what had imprisoned her all these years: she had never known what to desire. She had desired only the absence of loneliness when she should have desired the presence of love. She had desired to escape from madness. She should have desired to find passion. One desire had blocked the other. With that realization, Anna is freed from oppressive loneliness. She can see now that fate brought this young man to her. As she stares, he enters her soul through the portals of her eyes. [This is probably an amalgam of every Prince Charming–type cartoon I’ve ever seen—wordless stares and sighs somehow yield portentous meaning.] She and the young man have perfect understanding—and that is why he does not speak aloud. That is how intimately he knows me, she thinks. He knows I have always loved him, since the birth of eternity. She realizes something even more shocking: he has always loved her. He desires her love now as fiercely as she desires his. Without words, they make a vow: to meet the next day and express their love in all ways possible. And now, today, they will be able to speak to and touch each other for the first time.

2:50 Anna arrives at the tall gates of the village and finds herself in the town square, where streets radiate out like spokes. She does not know which to take. But before she becomes overly distressed, she discovers that her shoes know where to take her. She swiftly walks down one empty street to another. The houses seem empty and lifeless until curtains twitch, revealing the faces of busybodies. When she rounds one corner, she sees three stern-looking women in white caps and aprons scrubbing clothes. They stop their work and conversation to stare at her with a disapproving scowl. She is sure they know why she has come. She straightens her shoulders and walks erectly, casting off their opinions. She tells herself she won’t allow these loveless women to deter her. They envy me, she says to herself. But now her feet have grown heavy. It’s as if she is pushing through knee-high mud. To force herself to continue, she remembers the near-insanity of loneliness. She cannot go back. By remembering her lover’s face, she will find determination. She summons up the memory of their meeting, of his eyes locking on hers, making her blind to these women’s taunting faces. But now she cannot remember what color his eyes are. Once again, each step forward is weighted with certain disaster. Why can’t she remember his face—the one that freed her cramped heart to grow with desire? It is still growing right here on this street. It has grown into a heart so bloated with desire it might kill her. She can feel it pushing into her throat, choking her. She is about to turn back when she hears her inner voice ask: What use is self-respect if there is nothing else to live for? She had nearly gone mad with pride and propriety. She might have killed herself if it weren’t for his love. She throws off thoughts of scandal and wraps desire around her like a warm protective cloak. Newly found passion guides her once again, and each step grows lighter. Soon she is at her lover’s door. Her life, at last, is about to change. It is the end of loneliness.

4:05 Anna walks in. The dwelling is humble, the sort of place where a wood carver or young artist might live. She wonders, what does he do? Perhaps he descends from aristocrats who have become impoverished, like her family. [Impoverished daughters of aristocrats are a staple of fairy tales and nineteenth-century novels.] The ceiling is low and the room is small. A table and plank benches are set before a stone fireplace in the middle of the room. At the other end of the room is a narrow cot, where her lover is sleeping, dreaming of his impatience to see her. A square window facing the empty streets throws a slant of light on his face, this handsome youth. His hair is so blond it is nearly white, his face is pale, his eyelids and nostrils are a translucent pink, his nose is long, and his chin is small. It is obvious he is an aristocrat, a Russian princeling, unaccustomed to work, with a mind fit for noble purpose. She is eager to see the color of his eyes again.

She throws off her cloak and warms herself by the fire. The glow from the hearth makes the entire room rosy. In the past, she never gave a thought to her appearance. But in this soft light, she knows she is radiantly beautiful. She is about to call to him when he awakens and rushes over to embrace her. His possessive gaze and caress remove all doubts that she has made the right decision in following desire. He has healed her, and only then does she realize she has been ill. He has warmed her, and only then does she realize her bones have been cold. She sees in his eyes that she truly is beautiful. She has astonished him. In the flickering light, his eyes appear to be gray, then pale blue, turquoise, ice blue, and silver. He leads her to his bed, a low cot covered with a blanket of rabbit skins. As soon as she lies down, she casts off shyness and her clothes immediately follow. No one has ever touched her skin. His hands know this. They murmur and whisper nonsensical words. She cries, knowing his whispers are about her, that he is telling her about the dimensions of his love. She cannot make out exactly what he is saying and will have to ask him to repeat it later—although perhaps she already knows. After all, their thoughts and feelings are identical. The exquisite sensations of their bodies are identical. She exults aloud: These moments together have already been enough for a lifetime of dreaming.

As if her thoughts had been an incantation, the spell is broken. Their time together is over. [Shades of Cinderella, the plot driven by a mindless keeper of time.] He looks at her sadly. He seems to be telling her with his eyes. Time still divides us, but now we have eternity. They unwrap arms and legs, and from one body they are again two. She is instantly cold. He bids farewell, and when she steps out, she sees that it is early morning. The night passed as if it had been only a few moments before falling asleep.

6:17 Anna walks home, light-headed, still caught in the dream. The old ache of loneliness is gone. She can hardly remember how she once felt. She has a destination now, a reason to live. When she reaches home, she sees how dingy the rooms are, how cavernous and yet constricted the place feels with its small chambers and long hallways. How had she been able to bear it for so long? She wants to go to him this instant and tell him what she has suffered and what he has changed. Why did she leave him in the first place? She cannot recall his saying it was time for her to go, not in words. Perhaps he had wanted her to stay and was wounded in thinking she had made the decision to leave him. She should return to him now. But then she remembers his shuddering groan. He believed they should savor desire and not be consumed by it all at once. He is right. She will wait and come to him when he cannot bear to be without her, when he, too, feels life is meaningless without desire. Warmth will always be at the other end of the road and she now knows how to reach it.

6:55 The simple diatonic melody begins. Anna is once more on her way to her lover. She looks older. It is evident that years have passed. Her step is not quite as lively. The incline feels steeper. This is simply a journey to get to where she needs to be. It starts to rain and the road soon becomes muddy. She slips several times. She considers whether to turn back. She still desires him, but when she returned home yesterday, she wondered why desire was still there when it should have been fulfilled long ago. Her mind holds so many worries it is hard to think clearly about any of them. She does not know his name. He does not know hers. She had reasoned that it did not matter because they knew each other in more important ways. But how? She never asked him. She never asked that of herself. They have spoken only in grunts and gasps, the language of desire.

A wind comes up and rain beats faster and washes over Anna’s face like a waterfall, making it difficult to see. She is frightened. She cannot go any farther. In the distance she sees a hunched figure coming from the opposite direction. She soon realizes it is an old woman without the cover of a cloak. The woman’s unbound hair streams down her face like long moss. Her once fine dress is soiled, ripped at the armholes. The hem is shredded. She is a wretch of misfortune, Anna thinks, the daughter of a respected family who would now pull up her skirts for the promise of a penny. The old woman laughs, as if she had heard Anna’s unspoken insult. She shakes her head and throws Anna a pitying look. Anna is furious that this lowly harlot would pity her. A moment later, she is startled to see that the woman, although haggard, is not old at all. She could be her age, and in fact, they look so much alike they could have been twins. They have the same long dark hair, wide-set gray eyes, and a mole on the right cheek. Even the dresses would be identical if the whore’s were not dirty and hers were not clean. When she looks down at her dress, she sees for the first time a black oily spot, then another and another. She instantly feels cold, so brittle with cold her spine might snap. The beggar woman does not exist, she tells herself. It is worse. She is the malevolent twin of her imagination who has been waiting to be recognized. Anna tries to calculate how many years have passed since she began these repetitious journeys to her lover’s bed. How many mornings did she rise and leave the narrow cot with him still dozing? It must be thousands. Her skin must be worn thin from so many rubbings. She is afraid to look. Over the years, she refused to let questions about him enter into her mind. Yet she still felt tormented by small doubts: that he did not love her as much. Or that he did not even exist. The first time she had that thought, she immediately turned around on the road and rushed back to the village. On her way there, she noticed that the road had grown longer and steeper. When she reached his home, she peered through the window and saw him sleeping as usual. She was tempted to rap the window and see his delight that she had returned so soon. But then, as usual, she thought it was best to not interrupt his dreams of desire for her. She simply returned home.

But now, since meeting the wretch on the road, she cannot stop the worries. Does he still desire her? Is his desire the same as what he had for the harlot? Was that why the woman gave her a pitying look? What a brainless fool she has been. She should have banged on the window and broken the pane, then reached in and shaken him to make him speak. Does he, too, believe desire for her is life’s meaning? Who else has he desired? What does he do besides satisfy himself with her body? Her malevolent twin is delighted she has doubts. His incomprehensible groans and grunts were not promises of love, she tells Anna. They were lusty profanity in a foreign language. You saw him only between the hours of dusk and dawn. You had eyes for only what lay at the end of the road and not what surrounds you. Anna looks around her. The woman is not there. Who is speaking to her? She sees the trees around her are dead. How long have they been that way? She sees them as an omen. Love is withering, not just his, but hers. Soon she, too, will resemble the stiff dead trees she passes, their leafless branches clawing upward for more sky. [Shades of anthropomorphic trees in The Wizard of Oz.]

She turns around to go home. But she cannot. The more she resists, the stronger the wind blows against her.

10:30 In the past, she could do nothing but succumb to the delusion that he loved her. There is no delusion now. Knowledge is a murderer. She knows now she will not increase the small amount of happiness she receives from her lover. It does not accumulate but disintegrates as soon as she is on the road walking home. Her love for him will always remain gnawing desire. The old argument arises: if she refuses it, she will have nothing. She will be empty. She struggles to retain the vaporous illusion of love. No longer able to decide, she lies on the road and allows herself to be buffeted by the storm. She does not protect herself from the wind. She has already given up self-will. She will soon become a ghost of desire riding a beggar’s back. Why not end it now—but which, her life or her desire?

12:45 The storm ends. It has purged doubt, and she is grateful she has survived. She finally understands that her resistance to desire had only made desire stronger. Each time she had thought of turning back, desire surged and became fear, a madness that clawed at her until she pushed through her lover’s door again and lay on his bed. In the morning, he had let her out onto the streets where the laundry women could see her. She would then take the road home, carrying her useless satchel of self-knowledge. She had emptied her mind for him. She had welcomed him to use her body as a receptacle. She had asked for nothing. She would have done that until she disappeared—body, mind, and senses. Holding on to this terrible realization, she now turns around to go home. She pushes against strong winds. With each step, the road behind disappears.

13:17 Anna is home. The rain is nearly over. She finds calm for the first time being alone in her house. The arguments in her head are gone. In the past, she would have been frightened by quiet and loneliness. But now she knows she can leave her house whenever she wants. She does not need a destination based on desire. She walks outside and for the first time, she sees beauty in the landscape, in the slope of a small hill, in an enormous tree whose canopy is lit so brightly by the sun it looks like a veil of gold. This tree has always been there, and she now recognizes it as a place where she once sought refuge in a thunderstorm. She runs to the tree and climbs up to its crook. The leaves brush her skin. She sees the bright blue sky through the branches. There are so many ways to see sky. She spots a fat blue bird that sings to her. There are so many ways to see blue. Loveliness is unexpected. It comes without being asked for. How had she not known this? She looks out and sees the spire of the church of the village, the dark clouds moving toward it. And then the spire punctures the clouds and dark rain pours.

15:50 The simple diatonic melody returns. Anna is walking along the road again. Her pace is steady. She is confident. She will see him, her delusion of desire. For so many years, she had seen herself transformed in his lustful gaze. She had believed that the passion in his eyes had emanated from him, when in reality it had simply been her own reflection and longing. Without her desire, he will be empty. Without her passion, he does not exist. Without her shame, the scowling women become myth. They were all part of her delusion to make desire appear more important than it was. And with that realization, the road before her vanishes.

That is the end of the first movement. There are two more movements. And that is good, because the story of this woman does continue beyond a vanished road.

For the last thirty years, I’ve harbored a secret desire to compose music. I’ve had dreams that I already have. I hear it, my music, and am composing simultaneously with it being played by a full orchestra. The music is romantic in form. The song is lyrical. The strings play, the reed instruments come in, then the piano solo. The emotions are deep and wide. I know the themes of revelation. I see the partially written score before me, pages three feet wide and four feet tall. I am writing the score for all the instruments, in bars stacked atop each other. I sweep my hand over the paper and the notes appear. But then I wake and realize there is no score and that I lack the skills to transcribe even a note of what I heard. Yet I still feel a residual sense of wonder that the music came to me so easily. I’m frustrated that I can do nothing to retain it. And perhaps that is because there was nothing to retain.

The dreams of music are like the recurring dreams of a secret ballroom—an enormous unused room always found at the back of a house, past the dining room, or through a door in the laundry room. In the dream, I always wonder why I never noticed the room before. It could have solved my need for additional space for books or for a larger study or a painting studio. In one version of the dream, the ballroom is at the back of a third-floor Victorian apartment where I lived in the 1970s. In another, it is accessed via a cave in the yard of a ramshackle cottage where I lived when I was a student at UC Berkeley. There are three more dream houses, all different, but the ballroom is the same. It was once grand but now has plaster debris on the floor and chipped French blue paint on the walls, all easily fixed. Sometimes there is a smaller room beyond the ballroom. It is a mess, filled with construction materials, mops, buckets, saws, hammers, and a big concrete washbasin holding half-filled cans of paint. These are the materials I have to use to repair the ballroom. It is an enormous task. In some dreams, I am able to clean up the mess in a day and hold a dinner party at night. In other dreams, I decide to put off fixing up the room. I sweep the floor, then leave the house and discover I actually live in another house and the place I just left is a house I lived in twenty years ago and forgot I still owned. I’m flabbergasted. How could I have forgotten I own a house? I wonder how much it would fetch on the real estate market today.

These are the words I can use when I wake up to retain memory of the ballroom. I cannot use words to retain the music once I wake up. I don’t have the musical ability to take it with me. It lives in its own language—all except one tendril of music, which I managed to capture. As soon as I woke, I used my cell phone to record myself humming part of the dream melody before it disappeared. I played it back. It was a somber tune, almost baroque in quality. When I listened to it a month later, it did not seem like anything I would have devised. I concluded that the tune I hummed was vaguely familiar because it was a song from my past, a hymn from childhood, or any of the thousands of songs I’ve heard at symphonies or on the radio. It could be a passage from a soundtrack. Or perhaps it was a fugitive melody from someone else’s dream.

I have not given up on the idea that the music I hear in dreams can come alive in the waking world. I have had other things come to me in dreams. Cats that dip their tails in inkwells and write as instructed until one kitten has an accident. That became the children’s book Sagwa, the Chinese Siamese Cat. I dreamed of a full moon party on a boat, during which a little girl falls into the water and becomes lost. When she is found, she is a different person. That became the children’s book The Moon Lady. I dreamed the idea for making the narrator of a novel the ghost of my mother, who had just died. She suggested in the dream that she could serve as the omniscient guide to tourists on holiday in Myanmar, and per her wish, she became the voice in the novel Saving Fish from Drowning. All sorts of solutions to small plot problems have come through somnolent delivery. The best dream arrived two years ago: it was an entire novel—the setting, the narrator, other characters, the situation that leads to the narrative, accidents and bad timing, the other characters and their roles, a backstory in China, a family tree, the complications, even small scenes. When I woke, I wondered if it was the gibberish that is understandable only in dream logic. While it was still in my head, I wrote it down, as much as I could remember. Ten pages. Then I read what I had written and it all made sense.

The actual writing will still be daunting. It gets harder with each novel. I will have to relearn my craft, overcome the same doubts, untangle the narrative from long detours, or take whichever detour is the story I should tell. I will also find the right music to accompany the scenes as I write them. I am thinking it might even be some of the music that I have yet to dream. It doesn’t have to be a full orchestral piece—let us not be delusional. A simple motif would be enough, just four measures of it spun out into a melody that I could play on the piano in the clear voice of the right hand. It would require only a modest dream to deliver a motif barely hanging by a thread of intuition. I will hum it and capture it with a recorder, then transcribe the notes I hear onto a sheet of music. I will play freely with the motif, trying out variations, then transcribing five, the most emotionally resonant—onto sheet music. I will play that melodic motif a hundred times until it is engrained as emotional memory, as part of me. I will play that motif a thousand times for the novel that I have already dreamed I would write.