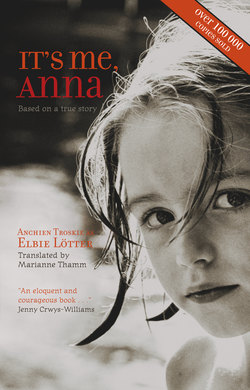

Читать книгу It's Me, Anna - Anchien Troskie - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Part 1

ОглавлениеI was eight years old when my mother brought Uncle Danie home. Eight. From then until I turned sixteen, my life was . . . different. That’s the only word I can think of to describe it – different. That’s why I’m in my car now, on an eight-hour journey – so that I can wipe out eight years of injustice, eight years of hell. If all goes well, at three o’clock tomorrow morning I’ll be standing at their door. Three o’clock on a weekday morning in Bloemfontein. That’s good. They’ll still be fast asleep. Most crimes take place in the dead hours of the morning, don’t they? But before I get there, before I am able to do anything, I have to make myself see all those things that I’ve suppressed for so long, that I’ve driven from my mind. Then, when I remember the pain, when I feel it, I’ll have the courage to do what I need to do. I have to see it all again, feel it. Like I’m going to see him now, like I’m going to smell his fear.

I was six when I first realised that all was not well between my mom and dad. I went to nursery school during the day when they were at work. My father was a sergeant in the South African Police and my mother worked in Bantu Administration. We lived in a small town in the Eastern Cape.

My mother and I were in the lounge. The radio played softly in the background. I was busy building a tower with my wooden blocks and my mom was just sitting there. Like a dead person. Or someone who wanted to die. Then my father walked in and she suddenly came to life.

“Look at him. Look at your father!” she shrieked. “He doesn’t love you any more, Anna. Or me.”

“Johanna!” my father warned, but my mom was beside herself.

“Do you want to hide the truth from your child?” She struggled for breath, then screamed even louder: “He loves another woman with three children more than he loves us. A slut! He wants to be with her, Anna. Alta the slut and her three children!”

Alta. I still hate that name with a passion. And I can’t distinguish that Alta from others – when I meet one, she immediately becomes the woman who stole my father, the one with three children whom my father loved more than me. I’m immediately antagonistic towards anyone with that name.

Without a word, my father walked past and went to shower. Then he lay on the double bed, smoking a cigarette. My mother got up and walked out. I went and lay down next to my dad, held tightly in his arms, like always. Then she walked in with his service revolver in her hand.

“You pig! You fucking pig! I’ll kill you. That’s what a man deserves for pushing his wife and child aside for another woman!”

I wasn’t scared. Maybe because I didn’t realise that you should be scared when your mother threatens to shoot your father and he pulls you across his chest and says, “Shoot, then.” Afterwards, whenever I remembered that incident, I wondered

who’d really loved me. My mother, who didn’t shoot, or my father, who used me to prevent her from shooting him like . . . a pig?

My father was the approachable one in our family. The one who always made time for me. Who dragged me off, sometimes unwillingly, to rugby and cricket matches. At these matches, he’d bring out oranges and roll them between his palms to soften them. The oranges were packed into two separate containers. Mine were plain orange – the sweet juice would drip down my chin and make my fingers sticky. My father would doctor his with syringes full of brandy the night before, and he was usually very jolly by the time the final whistle was blown. When we arrived home, full of laughter, especially when our team had won, my mom’s face would loom over us like a dark thundercloud. She wouldn’t say anything. Just send me off to my room after supper. She’d keep it all inside until she couldn’t stand it any more. Later, a torrent would explode from her mouth. She screamed at my dad, not at me. Not back then. As I lay curled up on my bed, wrapped in my blankets against the biting cold, words or snatches of conversation drifted through the walls. “How could you? Can’t you be more responsible? Think about how scared she must be when you look like this. Car crash . . . accident . . . You’re supposed to be a father, someone she can look up to.”

On and on until, eventually, I’d fall asleep from sheer exhaustion. I never heard my father’s voice. It was as if he wasn’t there, as if he had already left.

I mustered up enough courage to talk to my mother one Sunday morning after church.

“Mommy, Daddy looks after me when we go to rugby. I’m not afraid.”

“Anna,” she said, and went down on her haunches to look me in the eye, “I know you have fun, but it’s not the right way of doing things. Your father is supposed to protect you, with his life if needs be, and not place you in danger. That’s unfortunately what happens when he drinks and drives. He can make errors of judgement, and it gets dangerous. Do you understand?”

I didn’t, but I nodded. How could having fun with your father be dangerous? After that day, I was forbidden from going to watch rugby with my dad. I had to sit on the stoep and wave goodbye as he drove off.

The Saturday after my mom scolded my dad about his drinking and driving, we went fishing. I don’t know how my dad convinced Mom to allow me to go with him, but this time she didn’t say a word. She just hugged me tightly before I got into the car.

We never went fishing in the sea, even though it was close enough to our home. “Too rough,” my father would say. “I was born in the Free State. We catch fish, we don’t go angling – and definitely not in the sea.”

That’s why we went to the dam. It wasn’t a big dam, just large enough for fishing. It was a beautiful day, sunny and windless, and my father had packed enough food and cooldrink for both of us, so that we wouldn’t go hungry.

“Anna,” he said, not looking at me, but staring out at the water as if looking for help, “your mom and I have decided to get divorced. Do you know what divorced means?”

“Yes.” A lot of the parents of the children in my nursery-school class were divorced. It meant they had two houses and got two presents on their birthdays and at Christmas.

“Daddy wants you to know that Mommy and I love you very much. It’s not your fault that we’re getting divorced. We, your mom and I, just can’t be with each other any more. Do you understand?” He looked at me. “Anna, I’m so sorry that I’m doing this to you.”

The tears welled up in his eyes.

I held his hand and gave it a little squeeze. “It’s okay, Dad.”

I don’t remember much about the divorce itself. Only that my cat was run over on the same day and that my father came to tell me just before we moved out. My heart was broken. Was it because of the cat? The divorce? I don’t know. I just know that my heart still aches when I think about that day.

After the divorce, my mother and I moved to the city, near the sea. My father asked for a transfer and also came to live in the city. He rented a house close to the sea – “because I just miss my little girl so much,” he said.

My mom worked during the day and I stayed with Paulina. Paulina Willemse knocked on our door for work shortly after we’d moved in. You could see she’d lived a hard life. My mom must’ve felt sorry for her because she started working for us the very next day. Paulina stayed with us for many years. She sometimes used her own bus fare to buy me ice cream, especially when my mom had shouted at me. I’d lie on the mat and lick one side of the ice cream while Snowy, the white cat my mom bought me after we moved in, licked the other.

“Why do you buy me ice cream, Paulina? This afternoon you’ll have to walk home, and it’s far,” I asked.

“My children live with my sister. If I’m good to you, then the Lord will make sure that she’s also good to my children.” She stood with her hands folded across her stomach, which was slightly pushed out, a smile at the corners of her eyes and mouth. Paulina always stood that way. I loved her very much.

I had my cat, Paulina during the day, ballet twice a week, my mom at night and my father every second weekend. I was happy.

It was only later that I realised why they had to get divorced. I never blamed them for it – they were chalk and cheese. My mother was hyper-neat, a pain actually. She didn’t smoke, drink or throw parties. She hated all that. Mom went to church every Sunday, while I went to Sunday school. My dad drank and smoked – a lot. He was crazy about women and parties. My mother believed alcohol and parties were a lethal combination, and as usual she was right. My father had met Alta at a party. He’d jumped into bed with her after drinking too much, and ended up moving in with her and her three children, into a house paid for by her ex-husband. Just like my mother had always predicted.

Before I was born, my dad, who was a deacon in the church, had had an argument with the dominee. After a service, he hadn’t wanted to say a closing prayer in the vestry, but the dominee had forced him to. My father had vowed that he would never set foot in church again.

“People, Anna,” he once told me, “believe God lives in the church. That the dominee talks to Him for us. But they’re wrong. He lives here,” he said, pressing his hand to his chest. “If you don’t have Him in here, you won’t find Him in a church.”

My father only went back on his word once, and that was when I was christened. I suspect my mother threatened him with something terrible if he didn’t accompany her to the ceremony. Even at his funeral, we weren’t allowed to take his coffin into the church.

No, I never blamed them.

School was everything I’d dreamt of. I learnt to read and write and do sums. I loved all of it, but most of all I loved to read. With reading, there were no limits to my world. I really only began to see other children, the way they really were, in primary school – playful, fun-loving. Boys fascinated me. Maybe because I didn’t really know much about them. What was it that made them different? That’s why I didn’t hesitate when a boy in my class asked me during a break if I’d like to see his willy. We scuttled away from the other kids and stood in the shade of a tree. He pulled down his pants and gave me a quick flash. A little worm, I thought.

“I showed you mine, now show me yours!” he demanded.

I pulled my dress up and dropped my panties – but pulled them up again quickly when I saw the shocked expression on his face as he stared at something behind me.

Standing in Mr Van Pletzen’s office, at age seven, while he phones your mother to tell her what you’ve done is a terrifying experience.

She didn’t speak to me on the way home. “I can’t bear to look at you,” she said when we got there. I’ll never forget the disappointment and disgust in her eyes as she ordered me to my room. I couldn’t forgive myself for doing this to her. I knew that what I’d done was naughty, but I hadn’t realised it was so terribly naughty.

My mom phoned my dad. She told me I wasn’t allowed to leave my room when he arrived and that she wanted to talk to him in private. That night an entire conversation, not just disjointed words, drifted into my room. It was a one-sided monologue, as usual.

“Where did she learn to do that?”

Silence.

“It can’t be normal. Not all children do that.”

Silence.

“She gets it from you.”

Silence.

“It must be genetic.”

Silence.

“It’s not a joke. You’re not the one who had to face the school principal. What kind of child are we raising, you and me? A slut! It’s because you never stand your ground against her. She’s got you wrapped around her little finger.”

Silence.

My father had to take me to school the next day, because my mother still couldn’t bring herself to look at me. “Daddy,” I asked him as we stopped at the school gates, “what’s a slut?”

“Where did you hear that word?”

“I heard when Mom –”

He held up his hand, stopping me. “Anna, what you did yesterday isn’t a sin. You were just curious, and that’s normal. I know you didn’t mean to be naughty. And that’s all that matters, isn’t it?”

I nodded, still not sure what “slut” meant.

“Anna, no matter what you do, I want you to remember that I love you.”

“Mom says I’m a rotten apple. She says I have to listen to her and then our life together will be better.”

“Your mother says lots of things. I wouldn’t take any notice if I were you. Come on, run, the bell’s already gone.”

My mom didn’t speak to me for a long time after the episode at school. She was too angry. But one day she thawed, called me to the dining room and told me to sit down at the table.

“Anna,” she said, “I want you to listen to me carefully. Will you?”

I nodded.

“It’s just you and me now. Your father doesn’t want us any more. From now on I have to work harder and so must you. I want you to do your best at school. I want you to work hard. Do you understand?”

I nodded again.

“Anna,” she said with a deep sigh, “I’ve never spoken to you about that day at school.”

I hung my head. She needn’t have said anything else. I knew which day she was referring to.

“I just want to tell you that I’m not angry with you any more. But,” and she wagged her finger in my face, “you must never do it again. Do you hear me? What you did was dirty. Your hands will fall off if you fiddle down there. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Mom,” I replied timidly.

“Good.” She got up. “Then we understand each other. Anna, this is our chance to start over.”

Our lives took on a peaceful routine. We learnt to live with each other’s moods. Mom was less strict, more tolerant – even though she still forced me to wear dresses, which I hated. In the summer, my classmates would play in shorts while I sat around in frocks. I had two pairs of jeans and two tops that I left at Dad’s house. He’d bought them for me the previous holiday. I could wear them there. My mom hated jeans, she thought they were clothes that “ducktails” wore. I noticed that my father always wore neat long pants when he came to pick me up, but that he quickly changed into his jeans when we got to his house. The only thing he couldn’t hide was his beard. She hated that too. She would look at him disapprovingly but say nothing.

Weekends at my dad’s were the highlight of my life. He always bought a small present for me, but that wasn’t what I liked most. The best was just being together again, like in the old days. We’d watch rugby and go fishing, and there was no one to sneer at our catch. We cleaned the fish together, cut it up and braaied it.

My father didn’t live with Alta for very long. He’d still visit her, and on my weekends he’d call her late at night when I should already have been asleep. But I never saw her, and those weekends were mine alone.

My mother worked as a saleslady in a department store. She hated the job. “I have to find another job,” she often complained despairingly. “I feel that I’m in a dead-end street. It’s just the same routine over and over.”

I felt sorry for her sometimes. You could tell she wasn’t happy – her heart was broken over my dad and she hated her job. She cried a lot and sometimes she just stared out into nothingness. She didn’t pay me much attention. I didn’t hold it against her, but in some ways, the first two years on our own were hell. It was like standing outside in the cold and looking through a window at a happy family sitting around the fireplace inside. Of course a lot of my school friends’ parents were divorced, but there were others who didn’t come from broken homes. The difference between the two groups was obvious to me: children who came from happy homes seemed more relaxed, less moody, and not as desperate to please their teachers or their friends.

I was eight and in Sub B when Miss Lubbe handed out our first English reading books.

“Only read the first page for tomorrow,” was her instruction.

I couldn’t. I finished the whole book that same afternoon. I can’t recall the title, perhaps because it wasn’t important to me, but the story was about a giraffe, an elephant and a lion. The strange words were difficult to pronounce at first but it was easier the second time. The next day I proudly told Miss Lubbe that I’d finished the book. I could see she didn’t believe me.

“Should I read for you, Miss?” I offered.

She was so impressed that she dragged me around the school so that I could read for all the other teachers.

My mother was so proud she laughed out loud when I told her that night. I even got ice cream after supper. Mom so seldom laughed that I resolved to try even harder, so that she could be happy more often. She missed my father. I could tell, even though she never said so. But I knew it was him she longed for when she cried herself to sleep in bed at night. She was crying so much lately, especially after my father dropped me off at the end of a weekend. He always came inside and chatted to my mom for a while. Sometimes he’d have a cup of coffee. I always made sure I was wearing a dress when he dropped me off, crumpling the other dresses in my suitcase so that she wouldn’t find out and be angry with him. The only time her eyes lit up was when my father was there.

Then Mom brought Danie du Toit home.

“Remember I told you last week that I’d found a new job?” she said, smiling. “Well, this is my new boss.”

“Hello, pretty thing,” he said to me, bending to stroke my cat.

I liked him immediately. And why not? He was a handsome man, tall and dark with blue eyes. He thought I was pretty and he liked Snowy.

“My name is Uncle Danie. Your mom works for me. I’m the head of her department.”

“Hello, Uncle,” I greeted him politely, like my mom had taught me.

My mom got up to make coffee and Uncle Danie and I chatted. I don’t remember what we talked about, but he did tell me he had a son my age, who also lived with his mother. He said that next time he visited, he’d bring him along so we could play together.

“Are you happier at work now, Mom?” I asked as she offered Uncle Danie sugar and milk.

“Much,” she replied, looking at him and smiling.

“I’m glad.”

I was sent off to my room to play after they’d finished their coffee. Shortly afterwards I had a bath and went to bed.

My father started visiting us again. His relationship with Alta had ended when he’d walked in on her in bed with a girlfriend in broad daylight. My mom just shook her head and smiled triumphantly. “I told you!” she said, while my father stood there, hanging his head. I could sense the sadness in him.

After that my mom even accompanied us to a cricket match one Saturday to watch my father play. I was so proud of him – he was the wicketkeeper. My mom and I sat in the stands between all the other proud wives and children. I wore a dress, long, white knee-high socks and black shoes. Just like for church. There were no soft oranges this time. Instead, my mom occasionally filled a plastic glass with diluted Oros and passed it to me. The other children were drinking cans of Coke and eating ice cream.

Everything went so quickly, I still don’t know exactly what happened. The bowler ran up and bowled as my dad stood behind the wicket. Then Dad suddenly fell forward onto his knees and lifted his hands to his forehead. We could see the blood trickling through his fingers from where we sat. We rushed him to hospital. Luckily, there was no other damage, the doctor assured us. He was stitched up and admitted for the night. The stitches made a big X on his forehead and his left eye was starting to swell shut.

“Come and sit here with me,” he said, patting the bed next to him. I sat carefully so that I wouldn’t hurt him. “Don’t worry, Anna,” he said. “I’m okay. Only the good die young.”

My mom sat on the other side of the bed and held his hand.

Secretly, I hoped that they would find each other again.

But then Uncle Danie came to visit us again, and this time he brought his son along. I immediately disliked him. His name was also Danie. Danie Jr, his dad called him – little Danie. But there was nothing little about him. He was fat and he was a pain. He pulled my hair, kicked my cat and tattle-taled to his father. Uncle Danie never took Danie’s side when we fought, but my mom did. A few times I was ordered to go to my room for some crime or other, when Danie Jr was actually the culprit.

“Anna, make us some coffee,” my mom asked.

My heart sank. I was terrified that I’d drop the tray. It always felt so heavy. But I got up without saying anything.

“Do you always do what your mother says?” Uncle Danie asked as I carefully placed the tray on the coffee table.

“Yes.”

“She’d better. Anna and I have a good understanding. She knows I know better and that’s why she listens to me.”

“Do you hear that, Danie? I like obedient children,” he said to his son, with a look in his eyes that I didn’t recognise.

Uncle Danie’s visits became more regular. He’d take my mom out for dinner and sometimes they’d go dancing. Paulina would look after me. She’d sleep in my room because I was scared. I used to read her everything I could. Her favourite was You magazine – I had to read some of the articles over and over. When we heard my mom and Uncle Danie pull up, she’d grab her blankets and go and wait in the kitchen.

My dad also still visited regularly, but now he wore his jeans.

“Jo,” – he called her Jo when he was being affectionate – “can’t we try again? I promise, no booze,” he told her one night.

“I wish I could believe you, Hendrik,” – she always called him Hendrik, even when she was being loving – “but I can’t. I’ve met a man who’s like me. He doesn’t drink, he doesn’t smoke. He doesn’t like rugby or cricket or fishing. He’s well off and he can look after Anna and me.”

“Sounds more like a moffie than a man,” my dad grumbled.

I couldn’t help but laugh.

“Anna! Hendrik!” my mom rebuked us. “I love him, Hendrik.”

“But what about me? What about Anna?” my father asked.

“Anna is and will always be my responsibility. What we had was over long ago. You know that. If you have any feelings left for me, you’ll allow me my happiness. I don’t want you to come here any more. You only confuse Anna and create expectations that you can’t meet.”

“Don’t you think it’s good for Anna to see that her parents can still be friends?”

“No, I think that the truth is better. We can never be friends.”

He stopped coming in when he dropped me off or picked me up.

“Anna, I know you would like it if Dad and I got married again,” my mom tried to explain. “But it can’t be. A leopard can’t change his spots.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means that before you know it he’ll leave us again for another woman. Look at him. He knows I hate it when he wears jeans and that beard, but he still does it.”

“He’s got a doctor’s letter for the beard. It’s his skin.”

“A lie, that’s all it is.”

Uncle Danie did make my mom happy – she laughed more and more. As a bonus I surprised her with an A-plus average. Ten of the school’s best students were photographed for the local paper. Me too. My mother carefully cut out the photo, framed it and hung it in my bedroom.

My mom and Uncle Danie took us to the beach for my tenth birthday. It was a beautiful, cloudless day and the sea was a deep blue. I wore the shocking pink bikini that my mom had laid out for me on my bed the previous day. The gold chain with a heart that had my name engraved on it was around my neck. It was a birthday gift from my mom.

“What do you want for your birthday, Anna?” she’d asked the week before.

In the past I would’ve just shrugged. The excitement of not knowing what your present would be was sometimes more exciting than the gift itself. But this time I knew what I wanted.

“Clothes, please, Mom.”

“Clothes?” she said, surprised. “But you have a cupboard full of dresses.”

“I don’t want to wear dresses any more. I hate dresses! I want a pair of shorts, and jeans and T-shirts.”

“Anna.” My mother put on her here-comes-a-lecture face. “A woman must always look and feel like a woman. Jeans and shorts are fine for the beach, but otherwise they won’t make you feel feminine. A woman must be soft and giving. Pants make a woman look masculine. And we don’t want that. You’re a girl and you must look like one. Anyway, you’ve got a nice pair of pants for the winter, and your tracksuit.”

It wasn’t the same, but I kept quiet. It didn’t help to argue with my mom. You could never win. I got the gold chain. It was very pretty but I would’ve preferred clothes. She bought the bikini as a compromise. “See, this is wonderfully feminine. You’ll see – when you wear it, you’ll feel and look like a real princess.”

Uncle Danie was so sweet that day. He played with me and Danie Jr. He tickled me until it felt as if the laughter had squeezed all the air from my lungs. He didn’t mind if we threw sand at him. We laughed so much. Danie Jr and I ate ice cream and our hands got all sticky. We swam.

When Mom and Uncle Danie crawled under the umbrella to escape the worst of the sun, Danie Jr asked me to climb the highest dune with him. The sand scorched our feet, and with each step we dug our feet deeper in search of the coolness below. We reached the top and, as we hopped from one foot to the other on the hot sand, Danie Jr took off his T-shirt so we could sit on it to stop our bums from burning. We sat down close to each other, our feet buried in the sand. Out of breath, we scanned the beach for our mom and dad.

“You know they’re going to get married, hey?” he said.

“Who says?”

“My dad says. But not now. Later. He says they have to get to know each other really well first. He doesn’t want to make the same mistake he did with my mom.”

“My mom also always says my father was a mistake.”

“I like your mother.”

“I like your father.”

“I like my own mother more.”

“I also like my own father more,” I trumped him.

“If they get married, I’ll call your mother ‘Mom’.”

“Why?”

“Because I like her. Because my father would like it.”

I sat for a while and thought it over. What would my father say if I also called Uncle Danie “Dad”? Perhaps I shouldn’t tell him.

“Then I’ll also call your dad ‘Dad’.”

We looked at each other and burst out laughing.

“Then we won’t have to be ashamed at school any more because our parents are divorced or because we don’t have a brother or a sister,” Danie Jr said.

“Ja.” I’d never been ashamed of that. But that day I felt like agreeing with everything Danie Jr said.

After supper, Uncle Danie surprised us with a video he’d rented. “For the birthday girl because she looked so pretty in her bikini today.”

“Come on now,” my mom shooed us along, “put on your pyjamas and then we can watch.”

I ran – which was strictly against the rules – to get to the bathroom first. Mom didn’t scold me this time.

The television was in my mother’s room. The two adults lay on the bed and Danie Jr and I lay on the floor in front.

“Anna, come and lie here with us,” Uncle Danie said. “We can’t let the birthday girl lie on the floor.”

He moved over so that he could lie in the middle with my mom on the one side and me on the other.

I don’t know how it happened. At first I thought I was dreaming, but it was all too real. When I really became aware of it I realised that he’d slipped his left hand – the hand closest to me – under my panties. He was rubbing me – there, between my legs. I was numb with shock. I couldn’t move. Couldn’t Mom see? Maybe she did. Why didn’t she do something? Is this what fathers, or almost-stepfathers, are supposed to do to children? My father didn’t. Or would he still?

He pressed his mouth close to my ear. I could feel his hot breath and smell the sweet smell of Old Spice. “Shhht,” he whispered very softly. “It’s our secret. Because you’re so beautiful.”

He slipped his hand out of my panties when I started to jerk uncontrollably. Why did my legs feel so lame? Why couldn’t I speak? I only got up when I felt the life trickle back into my legs and my body had stopped shaking. “I’m tired, I’m going to bed.”

“But the movie isn’t finished yet!” Danie Jr complained.

“Leave her, I think she’s had too much sun. Sleep well, Anna.”

“You too, Mom.”

I walked to the toilet and waited a long time to pee. It just wouldn’t come. Then I went to bed. I felt so cold under the sheet and blankets that I sneaked out and fetched another blanket from the cupboard in the passage. It wasn’t enough. I lay there shivering. I was freezing.

Why did he do that? Why? I picked Snowy up from under my feet and stuffed him under the covers against my stomach so I could steal a bit of his warmth. He stretched himself out and began to purr. “I love you, Snow,” I whispered.

Later that night I woke up, suddenly aware of a strange wetness between my legs. Snowy had been gone for a long time and the spot where he’d been was cold and wet. I fetched some towels and wrapped them around me tightly, so I couldn’t feel the wetness. Early the next morning I packed the soggy towels back into the cupboard between the dry ones. I would tell Paulina about the towels later, and together we would think up a plan. I also put the extra blanket back in the cupboard.

I made up my bed myself. My mom was so proud of me. I couldn’t let her find out about the wetness in my bed. I wanted to tell her, but how? How would she react? I couldn’t, not after what had happened at school. I didn’t have the courage to talk to her about those sorts of things. There’d always been a gulf between us, and neither of us was prepared to build a bridge. My mother wouldn’t understand that it wasn’t my fault.

That Monday afternoon after school, I found the most beautiful doll on my bed. She was wearing exquisite clothes.

“A porcelain doll. Isn’t she beautiful?”

“She is! Thank you, Mom!

“She’s not from me, Anna. She’s from Uncle Danie. He spoils you terribly.”

The doll was beautiful, but if you looked carefully you could see the scorn in her eyes.