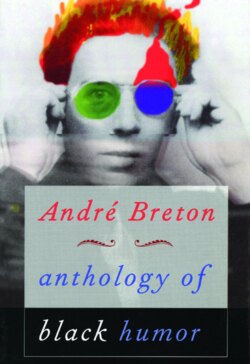

Читать книгу Anthology of Black Humor - André Breton - Страница 29

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ELEPHANT AND DOG

ОглавлениеLet us first define real and false virtue, by comparing the elephant with the dog, one of whom is the emblem of noble friendship and the other of false friendship.

1. Friendship.—It is noble in the elephant, and always compatible with honor. The elephant has none of the baseness of the dog, who, having been beaten for no reason, retains no memory of it. The elephant will endure just punishment, but he will not let himself be mistreated for no reason; he does not forgive offenses. Moreover, his friendship is as constant and devoted as the dog’s. This noble friendship is the kind that leads to collective and corporate bonds, while the servile friendship of the dog favors only despotism, the Civilized and barbarian regime that would hardly allow noble passions to flourish, as they do in the elephant. Despots prefer the friendship of the dog, who, unjustly mistreated and debased, still loves and serves the man who wronged him.

2. Love.—It is decent and faithful in the elephant; it is scandalous and criminal in the dog, who in love is the most ignoble of quadrupeds, uniting all vices in this passion; like the loves of the Civilized, in which wiles, fraud, and oppression hold sway.

3. Paternity.—It is judicious and honorable in the elephant. He does not wish to sire offspring who would be born to misery, and he will not procreate in slavery. It is a lesson for the Civilized, who murder their children by producing too many of them without being able to provide for their well-being. Morality or theories of false virtue stimulate them to manufacture cannon fodder, anthills of conscripts who are forced to sell themselves out of poverty. This improvident paternity is a false virtue, the selfishness of pleasure. Thus has nature preserved the elephant from this vice, making him the very model of the four affective passions taken in their truly social sense, passions that are suited to general relations. The dog, emblem of false virtues, embodies the kind of false paternity that engenders anthills, litters of eleven (the first of the anti-harmonic numbers), veritable heaps, three-quarters of which will perish by the knife, the tooth, or starvation.

4. Honor.—This is the fourth molded virtue in the elephant; but it is not the kind of moral honor that claims to disdain riches and recommends that one drink from cupped hands, like Diogenes. The elephant wants not only good food (eighty pounds of rice per day); he also appreciates luxurious clothing, edibles, dishware, and libation. He is humiliated when one switches from silverware to earthenware.

If the elephant is the model of the four social virtues, we must, for the fidelity of our portrait, take him as representative of the fate ridiculed virtue suffers in Civilization. Thus nature has covered him in mud. He himself likes to be covered in dust, in the image of the virtuous man who chooses the path of poverty rather than seeking out a fortune that he can attain only by practicing every vice, plunder, baseness, venality, injustice, trafficking, speculation, monopoly, and usury. Nature could have provided this noble animal with a rich coat like the tiger’s; but this would have been absurd and inaccurate, for in our societies real and truly honorable virtue leads only to poverty. I say real virtue and not philosophical virtues, such as the wisdom of the chameleon who lends himself to any infamy that will bear fortune.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Nature has given the elephant ivory defenses, very rich weapons, by analogy with our social status that allots luxury to force, to the unproductive dominant class. Thus his trunk, which is simultaneously a weapon and a machine, is poorly dressed because it is productive, and the elephant must represent the state of industry and virtue falling victim to injustice and mockery. As an emblem of virtue’s fate, he is laughable behind by the contrast between his rump and his scrawny, graceless tail.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

The extreme smallness of his eyes make for a shocking contrast with the huge dimensions of his body. It depicts the narrow views of the virtuous man.… His ears are the opposite of his eyes. Their immense mass and flattened form figure the suffering of the man of good will who hears only the language of hypocrisy and perversity in our societies, in which some preach virtue without practicing it and others brazenly preach joyful vice. The just man is overwhelmed and offended by this double language of debasement; his ear is flattened from hearing only falseness: this ill-being is externalized in the elephant’s ear.

—from Final Analogies

† “Publication des manuscrits de Fourier,” vol. 4.