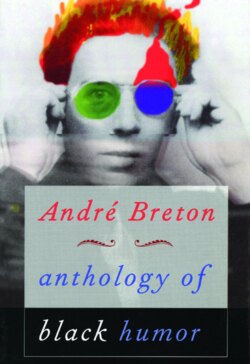

Читать книгу Anthology of Black Humor - André Breton - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

JONATHAN SWIFT

1667 – 1745

ОглавлениеWhen it comes to black humor, everything designates him as the true initiator. In fact, it is impossible to coordinate the fugitive traces of this kind of humor before him, not even in Heraclitus and the Cynics or in the works of the Elizabethan dramatic poets. Swift’s incontestable originality, the perfect unity of his production viewed from the angle of the very special and almost unprecedented emotion it elicits, the unsurpassable character, from this same viewpoint, of his many varied successes historically justify his being presented as the first black humorist. Contrary to what Voltaire might have said, Swift was in no sense a “perfected Rabelais.” He shared to the smallest possible degree Rabelais’s taste for innocent, heavy-handed jokes and his constant drunken good humor. In the same way, he stood opposite Voltaire in his entire way of reacting to the spectacle of life, as their two death masks so expressively attest: one bearing a perpetual snicker, the mask of a man who grasped things by reason and never by feeling, and who enclosed himself in skepticism; the other impassive, glacial, the mask of a man who grasped life in a wholly different way, and who was constantly outraged. It has been remarked that Swift “provokes laughter, but does not share in it.” It is precisely at this price that humor, in the sense we understand it, can externalize the sublime element that, according to Freud, is inherent in it, and transcend the merely comic. Again in this respect, Swift can rightfully be considered the inventor of “savage” or “gallows” humor. The profoundly singular turn of his mind inspired in him a series of diversions and reflections on the order of “The Lady’s Dressing Room” and the “Meditation Upon a Broom-Stick,” which partake of a remarkably modern spirit, and are responsible in and of themselves for the fact that perhaps no body of work is less out of date.

Swift’s eyes were, it seems, so changeable that they could turn from light blue to black, from the candid to the terrible. This variation perfectly matches his ways of feeling: “I have ever,” he says, “hated all nations, professions, and communities, and all my love is towards individuals…. But principally I hate and detest that animal called man, although I heartily love John, Peter, Thomas, and so forth.” The man who more than anyone despised the human race was no less possessed by a frantic need for justice. He wandered through the ministries of Dublin and his little vicarage in Laracor, anxious to know whether he was meant to look after his willows and enjoy the playing of his trout or to meddle with affairs of state. He did meddle with them, moreover, as if despite himself and on several occasions, in the most active and effective way. “That Irishman,” it was said, “who considers himself an exile in his own country, has yet to reside elsewhere; that Irishman, always ready to speak ill of Ireland, risked for her his fortune, his freedom, his life, and saved her, for almost a century, from the slavery with which England threatened it.” In the same way, the misogynistic author of the “Letter to a Young Lady on Her Marriage” was doomed in his own life to the worst emotional complications: three women, Varina, Stella, and Vanessa, fought over his love, and, if he broke with the first in a shower of insults, he was condemned to see the other two tear each other apart and die without having forgiven him. It was to this priest that one of them wrote: “Was I an Enthusiast still you’d be the Deity I should worship.” From one end of his life to the other, his misanthropy was the only disposition that never altered, and that events never belied. He had said one day, pointing to a tree struck by lightning, “I shall be like that tree; and die first at the top.” As if for having wished to reach “the sublime and refined point of felicity … the possession of being well-deceived; the serene peaceful state of being a fool among knaves,” he saw himself decline, in 1736, into a mental enfeeblement whose progress he was able to follow for ten years, with horrible lucidity. In his will, he left ten thousand pounds to build a hospital for the insane.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: A Tale of a Tub, 1704. The Works of Sir William Temple, 1720. Gulliver’s Travels, 1726. Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, 1727-1735. Directions to Servants, 1751, etc.