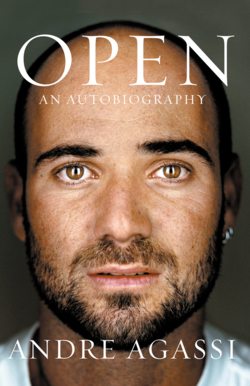

Читать книгу Open: An Autobiography - Andre Agassi - Страница 7

The End

ОглавлениеI OPEN MY EYES and don’t know where I am or who I am. Not all that unusual—I’ve spent half my life not knowing. Still, this feels different. This confusion is more frightening. More total.

I look up. I’m lying on the floor beside the bed. I remember now. I moved from the bed to the floor in the middle of the night. I do that most nights. Better for my back. Too many hours on a soft mattress causes agony. I count to three, then start the long, difficult process of standing. With a cough, a groan, I roll onto my side, then curl into the fetal position, then flip over onto my stomach. Now I wait, and wait, for the blood to start pumping.

I’m a young man, relatively speaking. Thirty-six. But I wake as if ninety-six. After three decades of sprinting, stopping on a dime, jumping high and landing hard, my body no longer feels like my body, especially in the morning. Consequently my mind doesn’t feel like my mind. Upon opening my eyes I’m a stranger to myself, and while, again, this isn’t new, in the mornings it’s more pronounced. I run quickly through the basic facts. My name is Andre Agassi. My wife’s name is Stefanie Graf. We have two children, a son and daughter, five and three. We live in Las Vegas, Nevada, but currently reside in a suite at the Four Seasons hotel in New York City, because I’m playing in the 2006 U.S. Open. My last U.S. Open. In fact my last tournament ever. I play tennis for a living, even though I hate tennis, hate it with a dark and secret passion, and always have.

As this last piece of identity falls into place, I slide to my knees and in a whisper I say: Please let this be over.

Then: I’m not ready for it to be over.

Now, from the next room, I hear Stefanie and the children. They’re eating breakfast, talking, laughing. My overwhelming desire to see and touch them, plus a powerful craving for caffeine, gives me the inspiration I need to hoist myself up, to go vertical. Hate brings me to my knees, love gets me on my feet.

I glance at the bedside clock. Seven thirty. Stefanie let me sleep in. The fatigue of these final days has been severe. Apart from the physical strain, there is the exhausting torrent of emotions set loose by my pending retirement. Now, rising from the center of the fatigue comes the first wave of pain. I grab my back. It grabs me. I feel as if someone snuck in during the night and attached one of those anti-theft steering wheel locks to my spine. How can I play in the U.S. Open with the Club on my spine? Will the last match of my career be a forfeit?

I was born with spondylolisthesis, meaning a bottom vertebra that parted from the other vertebrae, struck out on its own, rebelled. (It’s the main reason for my pigeon-toed walk.) With this one vertebra out of sync, there’s less room for the nerves inside the column of my spine, and with the slightest movement the nerves feel that much more crowded. Throw in two herniated discs and a bone that won’t stop growing in a futile effort to protect the damaged area, and those nerves start to feel downright claustrophobic. When the nerves protest their cramped quarters, when they send out distress signals, a pain runs up and down my leg that makes me suck in my breath and speak in tongues. At such moments the only relief is to lie down and wait. Sometimes, however, the moment arrives in the middle of a match. Then the only remedy is to alter my game—swing differently, run differently, do everything differently. That’s when my muscles spasm. Everyone avoids change; muscles can’t abide it. Told to change, my muscles join the spinal rebellion, and soon my whole body is at war with itself.

Gil, my trainer, my friend, my surrogate father, explains it this way: Your body is saying it doesn’t want to do this anymore.

My body has been saying that for a long time, I tell Gil. Almost as long as I’ve been saying it.

Since January, however, my body has been shouting it. My body doesn’t want to retire—my body has already retired. My body has moved to Florida and bought a condo and white Sansabelts. So I’ve been negotiating with my body, asking it to come out of retirement for a few hours here, a few hours there. Much of this negotiation revolves around a cortisone shot that temporarily dulls the pain. Before the shot works, however, it causes its own torments.

I got one yesterday, so I could play tonight. It was the third shot this year, the thirteenth of my career, and by far the most alarming. The doctor, not my regular doctor, told me brusquely to assume the position. I stretched out on his table, face down, and his nurse yanked down my shorts. The doctor said he needed to get his seven-inch needle as close to the inflamed nerves as possible. But he couldn’t enter directly, because my herniated discs and bone spur were blocking the path. His attempts to circumvent them, to break the Club, sent me through the roof. First he inserted the needle. Then he positioned a big machine over my back to see how close the needle was to the nerves. He needed to get that needle almost flush against the nerves, he said, without actually touching. If it were to touch the nerves, even if it were to only nick the nerves, the pain would ruin me for the tournament. It could also be life-changing. In and out and around, he maneuvered the needle, until my eyes filled with water.

Finally he hit the spot. Bull’s-eye, he said.

In went the cortisone. The burning sensation made me bite my lip. Then came the pressure. I felt infused, embalmed. The tiny space in my spine where the nerves are housed began to feel vacuum packed. The pressure built until I thought my back would burst.

Pressure is how you know everything’s working, the doctor said.

Words to live by, Doc.

Soon the pain felt wonderful, almost sweet, because it was the kind that you can tell precedes relief. But maybe all pain is like that.

MY FAMILY IS GROWING LOUDER. I limp out to the living room of our suite. My son, Jaden, and my daughter, Jaz, see me and scream. Daddy, Daddy! They jump up and down and want to leap on me. I stop and brace myself, stand before them like a mime imitating a tree in winter. They stop just before leaping, because they know Daddy is delicate these days, Daddy will shatter if they touch him too hard. I pat their faces and kiss their cheeks and join them at the breakfast table.

Jaden asks if today is the day.

Yes.

You’re playing?

Yes.

And then after today are you retire?

A new word he and his younger sister have learned. Retired. When they say it, they always leave off the last letter. For them it’s retire, forever ongoing, permanently in the present tense. Maybe they know something I don’t.

Not if I win, son. If I win tonight, I keep playing.

But if you lose—we can have a dog?

To the children, retire equals puppy. Stefanie and I have promised them that when I stop training, when we stop traveling the world, we can buy a puppy. Maybe we’ll name him Cortisone.

Yes, buddy, when I lose, we will buy a dog.

He smiles. He hopes Daddy loses, hopes Daddy experiences the disappointment that surpasses all others. He doesn’t understand—and how will I ever be able to explain it to him?—the pain of losing, the pain of playing. It’s taken me nearly thirty years to understand it myself, to solve the calculus of my own psyche.

I ask Jaden what he’s doing today.

Going to see the bones.

I look at Stefanie. She reminds me she’s taking them to the Museum of Natural History. Dinosaurs. I think of my twisted vertebrae. I think of my skeleton on display at the museum with all the other dinosaurs. Tennis-aurus Rex.

Jaz interrupts my thoughts. She hands me her muffin. She needs me to pick out the blueberries before she eats it. Our morning ritual. Each blueberry must be surgically removed, which requires precision, concentration. Stick the knife in, move it around, get it right up to the blueberry without touching. I focus on her muffin and it’s a relief to think about something other than tennis. But as I hand her the muffin, I can’t pretend that it doesn’t feel like a tennis ball, which makes the muscles in my back twitch with anticipation. The time is drawing near.

AFTER BREAKFAST, after Stefanie and the kids have kissed me goodbye and run off to the museum, I sit quietly at the table, looking around the suite. It’s like every hotel suite I’ve ever had, only more so. Clean, chic, comfortable—it’s the Four Seasons, so it’s lovely, but it’s still just another version of what I call Not Home. The non-place we exist as athletes. I close my eyes, try to think about tonight, but my mind drifts backward. My mind these days has a natural backspin. Given half a chance it wants to return to the beginning, because I’m so close to the end. But I can’t let it. Not yet. I can’t afford to dwell too long on the past. I get up and walk around the table, test my balance. When I feel fairly steady I walk gingerly to the shower.

Under the hot water I groan and scream. I bend slowly, touch my quads, start to come alive. My muscles loosen. My skin sings. My pores fly open. Warm blood goes sluicing through my veins. I feel something begin to stir. Life. Hope. The last drops of youth. Still, I make no sudden movements. I don’t want to do anything to startle my spine. I let my spine sleep in.

Standing at the bathroom mirror, toweling off, I stare at my face. Red eyes, gray stubble—a face totally different from the one with which I started. But also different from the one I saw last year in this same mirror. Whoever I might be, I’m not the boy who started this odyssey, and I’m not even the man who announced three months ago that the odyssey was coming to an end. I’m like a tennis racket on which I’ve replaced the grip four times and the strings seven times—is it accurate to call it the same racket? Somewhere in those eyes, however, I can still vaguely see the boy who didn’t want to play tennis in the first place, the boy who wanted to quit, the boy who did quit many times. I see that golden-haired boy who hated tennis, and I wonder how he would view this bald man, who still hates tennis and yet still plays. Would he be shocked? Amused? Proud? The question makes me weary, lethargic, and it’s only noon.

Please let this be over.

I’m not ready for it to be over.

The finish line at the end of a career is no different from the finish line at the end of a match. The objective is to get within reach of that finish line, because then it gives off a magnetic force. When you’re close, you can feel that force pulling you, and you can use that force to get across. But just before you come within range, or just after, you feel another force, equally strong, pushing you away. It’s inexplicable, mystical, these twin forces, these contradictory energies, but they both exist. I know, because I’ve spent much of my life seeking the one, fighting the other, and sometimes I’ve been stuck, suspended, bounced like a tennis ball between the two.

Tonight: I remind myself that it will require iron discipline to cope with these forces, and whatever else comes my way. Back pain, bad shots, foul weather, self-loathing. It’s a form of worry, this reminder, but also a meditation. One thing I’ve learned in twenty-nine years of playing tennis: Life will throw everything but the kitchen sink in your path, and then it will throw the kitchen sink. It’s your job to avoid the obstacles. If you let them stop you or distract you, you’re not doing your job, and failing to do your job will cause regrets that paralyze you more than a bad back.

I lie on the bed with a glass of water and read. When my eyes get tired I click on the TV. Tonight, Round Two of the U.S. Open! Will this be Andre Agassi’s farewell? My face flashes on the screen. A different face than the one in the mirror. My game face. I study this new reflection of me in the distorted mirror that is TV and my anxiety rises another click or two. Was that the final commercial? The final time CBS will ever promote one of my matches?

I can’t escape the feeling that I’m about to die.

It’s no accident, I think, that tennis uses the language of life. Advantage, service, fault, break, love, the basic elements of tennis are those of everyday existence, because every match is a life in miniature. Even the structure of tennis, the way the pieces fit inside one another like Russian nesting dolls, mimics the structure of our days. Points become games become sets become tournaments, and it’s all so tightly connected that any point can become the turning point. It reminds me of the way seconds become minutes become hours, and any hour can be our finest. Or darkest. It’s our choice.

But if tennis is life, then what follows tennis must be the unknowable void. The thought makes me cold.

Stefanie bursts through the door with the kids. They flop on the bed, and my son asks how I’m feeling.

Fine, fine. How were the bones?

Fun!

Stefanie gives them sandwiches and juice and hustles them out the door again.

They have a playdate, she says.

Don’t we all.

Now I can take a nap. At thirty-six, the only way I can play a late match, which could go past midnight, is if I get a nap beforehand. Also, now that I know roughly who I am, I want to close my eyes and hide from it. When I open my eyes, one hour has passed. I say aloud, It’s time. No more hiding. I step into the shower again, but this shower is different from the morning shower. The afternoon shower is always longer—twenty-two minutes, give or take—and it’s not for waking up or getting clean. The afternoon shower is for encouraging myself, coaching myself.

Tennis is the sport in which you talk to yourself. No athletes talk to themselves like tennis players. Pitchers, golfers, goalkeepers, they mutter to themselves, of course, but tennis players talk to themselves—and answer. In the heat of a match, tennis players look like lunatics in a public square, ranting and swearing and conducting Lincoln-Douglas debates with their alter egos. Why? Because tennis is so damned lonely. Only boxers can understand the loneliness of tennis players—and yet boxers have their corner men and managers. Even a boxer’s opponent provides a kind of companionship, someone he can grapple with and grunt at. In tennis you stand face-to-face with the enemy, trade blows with him, but never touch him or talk to him, or anyone else. The rules forbid a tennis player from even talking to his coach while on the court. People sometimes mention the track-and-field runner as a comparably lonely figure, but I have to laugh. At least the runner can feel and smell his opponents. They’re inches away. In tennis you’re on an island. Of all the games men and women play, tennis is the closest to solitary confinement, which inevitably leads to self-talk, and for me the self-talk starts here in the afternoon shower. This is when I begin to say things to myself, crazy things, over and over, until I believe them. For instance, that a quasi-cripple can compete at the U.S. Open. That a thirty-six-year-old man can beat an opponent just entering his prime. I’ve won 869 matches in my career, fifth on the all-time list, and many were won during the afternoon shower.

With the water roaring in my ears—a sound not unlike twenty thousand fans—I recall particular wins. Not wins the fans would remember, but wins that still wake me at night. Squillari in Paris. Blake in New York. Pete in Australia. Then I recall a few losses. I shake my head at the disappointments. I tell myself that tonight will be an exam for which I’ve been studying twenty-nine years. Whatever happens tonight, I’ve already been through it at least once before. If it’s a physical test, if it’s mental, it’s nothing new.

Please let this be over.

I don’t want it to be over.

I start to cry. I lean against the wall of the shower and let go.

I GIVE MYSELF STRICT ORDERS as I shave: Take it one point at a time. Make him work for everything. No matter what happens, hold your head up. And for God’s sake enjoy it, or at least try to enjoy moments of it, even the pain, even the losing, if that’s what’s in store.

I think about my opponent, Marcos Baghdatis, and wonder what he’s doing at this moment. He’s new to the tour, but not your typical newcomer. He’s ranked number eight in the world. He’s a big strong Greek kid from Cyprus, in the middle of a superb year. He’s reached the final of the Australian Open and the semis of Wimbledon. I know him fairly well. During last year’s U.S. Open we played a practice set. Typically I don’t play practice sets with other players during a Grand Slam, but Baghdatis asked with disarming grace. A TV show from Cyprus was doing a piece about him, and he asked if it would be all right if they filmed us practicing. Sure, I said. Why not? I won the practice set, 6-2, and afterward he was all smiles. I saw that he’s the type who smiles when he’s happy or nervous, and you can’t tell which. It reminded me of someone, but I couldn’t think who.

I told Baghdatis that he played a little like me, and he said it was no accident. He grew up with pictures of me on his bedroom wall, patterned his game after mine. In other words, tonight I’ll be playing my mirror image. He’ll play from the back of the court, take the ball early, swing for the fences, just like me. It’s going to be toe-to-toe tennis, each of us trying to impose our will, each of us looking for chances to smoke a backhand up the line. He doesn’t have an overwhelming serve, nor do I, which means long points, long rallies, lots of energy and time expended. I brace myself for flurries, combinations, a tennis of attrition, the most brutal form of the sport.

Of course the one stark difference between me and Baghdatis is physical. We have different bodies. He has my former body. He’s nimble, fast, spry. I’ll have to beat the younger version of myself if I am to keep the older version going. I close my eyes and say: Control what you can control.

I say it again, aloud. Saying it aloud makes me feel brave.

I shut off the water and stand, shivering. How much easier it is to be brave under a stream of piping hot water. I remind myself, however, that hot-water bravery isn’t true bravery. What you feel doesn’t matter in the end; it’s what you do that makes you brave.

STEFANIE AND THE KIDS RETURN. Time to make the Gil Water.

I sweat a lot, more than most players, so I need to begin hydrating many hours before a match. I down quarts of a magic elixir invented for me by Gil, my trainer for the last seventeen years. Gil Water is a blend of carbs, electrolytes, salt, vitamins, and a few other ingredients Gil keeps a closely guarded secret. (He’s been tinkering with his recipe for two decades.) He usually starts force-feeding me Gil Water the night before a match, and keeps forcing me right up to match time. Then I sip it as the match wears on. At different stages I sip different versions, each a different color. Pink for energy, red for recovery, brown for replenishment.

The kids love helping me mix Gil Water. They fight over who gets to scoop out the powders, who gets to hold the funnel, who gets to pour it all into plastic water bottles. No one but me, however, can pack the bottles into my bag, along with my clothes and towels and books and shades and wristbands. (My rackets, as always, go in later.) No one but me touches my tennis bag, and when it’s finally packed, it stands by the door, like an assassin’s kit, a sign that the day has lurched that much closer to the witching hour.

At five, Gil rings from the lobby.

He says, You ready? Time to throw down. It’s on, Andre. It’s on.

Nowadays everyone says It’s on, but Gil has been saying it for years, and no one says it the way he does. When Gil says It’s on, I feel my booster rockets fire, my adrenaline glands pump like geysers. I feel as if I can lift a car over my head.

Stefanie gathers the children at the door and tells them it’s time for Daddy to leave. What do you say, guys?

Jaden shouts, Kick butt, Daddy!

Kick butt, Jaz says, copying her brother.

Stefanie kisses me and says nothing, because there’s nothing to say.

IN THE TOWN CAR Gil sits in the front seat, dressed sharp. Black shirt, black tie, black jacket. He dresses for every match as if it’s a blind date or a mob hit. Now and then he checks his long black hair in the side mirror or rearview. I sit in the backseat with Darren, my coach, an Aussie who always rocks a Hollywood tan and the smile of a guy who just hit the Powerball. For a few minutes no one says anything. Then Gil speaks the lyrics of one of our favorites, an old Roy Clark ballad, and his deep basso fills the car:

Just going through the motions and pretending we have something left to gain—

He looks to me, waits.

I say, We Can’t Build a Fire in the Rain.

He laughs. I laugh. For a second I forget my nervous butterflies.

Butterflies are funny. Some days they make you run to the toilet. Other days they make you horny. Other days they make you laugh, and long for the fight. Deciding which type of butterflies you’ve got going (monarchs or moths) is the first order of business when you’re driving to the arena. Figuring out your butterflies, deciphering what they say about the status of your mind and body, is the first step to making them work for you. One of the thousand lessons I’ve learned from Gil.

I ask Darren for his thoughts on Baghdatis. How aggressive do I want to be tonight? Tennis is about degrees of aggression. You want to be aggressive enough to control a point, not so aggressive that you sacrifice control and expose yourself to unnecessary risk. My questions about Baghdatis are these: How will he try to hurt me? If I hit a backhand crosscourt to start a point, some players will be patient, others will make a statement right away, crush the ball up the line or come hard to the net. Since I’ve never played Baghdatis outside of our one practice set, I want to know how he’ll react to conservative play. Will he step up and jack that routine crosscourt, or lie back, bide his time?

Darren says, Mate, I think if you get too conservative on your rally shot, you can expect this guy to move around it and hurt you with his forehand.

I see.

As far as his backhand goes, he can’t hit it easily up the line. He won’t be quick to pull that trigger. So if you find he is hitting backhands up the line, that definitely means you’re not putting enough steam on your rally shot.

Does he move well?

Yes, he’s a good mover. But he’s not comfortable being on the defensive. He’s a better mover offensively than defensively.

Hm.

We pull up to the stadium. Fans are milling about. I sign a few autographs, then duck through a small door. I walk down a long tunnel and into the locker room. Gil goes off to consult with security. He always wants them to know exactly when we’re going out to the court to practice, and when we’re coming back. Darren and I drop our bags and walk straight to the training room. I lie on a table and beg the first trainer who comes near me to knead my back. Darren ducks out and returns five minutes later, carrying eight freshly strung rackets. He sets them atop my bag. He knows I want to place them in the bag myself.

I obsess about my bag. I keep it meticulously organized, and I make no apologies for this anal retentiveness. The bag is my briefcase, suitcase, toolbox, lunchbox, and palette. I need it just right, always. The bag is what I carry onto the court, and what I carry off, two moments when all my senses are extra acute, so I can feel every ounce of its weight. If someone were to slip a pair of argyle socks into my tennis bag, I’d feel it. The tennis bag is a lot like your heart—you have to know what’s in it at all times.

It’s also a question of functionality. I need my eight rackets stacked chronologically in the tennis bag, the most recently strung racket on the bottom and the least recently strung on the top, because the longer a racket sits, the more tension it loses. I always start a match with the racket strung least recently, because I know that’s the racket with the loosest tension.

My racket stringer is old school, Old World, a Czech artiste named Roman. He’s the best, and he needs to be: a string job can mean the difference in a match, and a match can mean the difference in a career, and a career can mean the difference in countless lives. When I pull a fresh racket from my bag and try to serve out a match, the string tension can be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Because I’m playing for my family, my charitable foundation, my school, every string is like a wire in an airplane engine. Given all that lies beyond my control, I obsess about the few things I can control, and racket tension is one such thing.

So vital is Roman to my game that I take him on the road. He’s officially a resident of New York, but when I’m playing in Wimbledon, he lives in London, and when I’m playing in the French Open, he’s a Parisian. Occasionally, feeling lost and lonely in some foreign city, I’ll sit with Roman and watch him string a few rackets. It’s not that I don’t trust him. Just the opposite: I’m calmed, grounded, inspired by watching a craftsman. It reminds me of the singular importance in this world of a job done well.

The raw rackets come to Roman in a great big box from the factory, and they’re always a mess. To the naked eye they look identical; to Roman they’re as different as faces in a crowd. He spins them, back and forth, furrows his brow, then makes his calculations. At last he begins. He starts by removing the factory grip and putting on my grip, the custom grip I’ve had since I was fourteen. My grip is as personal as my thumbprint, a by-product not just of my hand shape and finger length but the size of my calluses and the force of my squeeze. Roman has a mold of my grip, which he applies to the racket. Then he wraps the mold with calfskin, which he pounds thinner and thinner until it’s the width he wants. A millimeter difference, near the end of a four-hour match, can feel as irritating and distracting as a pebble in my shoe.

With the grip just so, Roman laces in the synthetic strings. He tightens them, loosens them, tightens them, tunes them as carefully as strings on a viola. Then he stencils them and vigorously waves them through the air, to let the stenciling dry. Some stringers stencil the rackets right before match time, which I find wildly inconsiderate and unprofessional. The stencil rubs off on the balls, and there’s nothing worse than playing a guy who gets red and black paint on the balls. I like order and cleanliness, and that means no stencil-specked balls. Disorder is distraction, and every distraction on the court is a potential turning point.

Darren opens two cans of balls and shoves two balls in his pocket. I take a gulp of Gil Water, then a last leak before warm-ups. James, the security guard, leads us into the tunnel. As usual he’s squeezed into a tight yellow security shirt, and he gives me a wink, as if to say, We security guards are supposed to be impartial, but I’m rooting for you.

James has been at the U.S. Open almost as long as I have. He’s led me down this tunnel before and after glorious wins and excruciating losses. Large, kind, with tough-guy scars that he wears with pride, James is a bit like Gil. It’s almost as though he takes over for Gil during those few hours on the court, when I’m outside Gil’s sphere of influence. There are people you count on seeing at the U.S. Open—office staffers, ball boys, trainers—and their presence is always reassuring. They help you remember where and who you are. James is at the top of that list. He’s one of the first people I look for when I walk into Arthur Ashe Stadium. Seeing him, I know I’m back in New York, and I’m in good hands.

Ever since 1993, when a spectator in Hamburg rushed onto the court and stabbed Monica Seles during a match, the U.S. Open has positioned one security guard behind each player’s chair during all breaks and changeovers. James always makes sure to be the one behind my chair. His inability to remain impartial is endlessly charming. During a grueling match, I’ll often catch James looking concerned, and I’ll whisper, Don’t worry, James, I’ve got this chump today. It always makes him chuckle.

Now, walking me out to the practice courts, he’s not chuckling. He looks sad. He knows that this could be our last night together. Still, he doesn’t deviate from our pre-match ritual. He says the same thing he always says:

Let me help you with that bag.

No, James, no one carries my bag but me.

I’ve told James that when I was seven years old I saw Jimmy Connors make someone carry his bag, as though he were Julius Caesar. I vowed then and there that I would always carry my own.

OK, James says, smiling. I know, I know. I remember. Just wanted to help.

Then I say: James, you got my back today?

I got your back, baby. I got it. Don’t worry about nothing. Just take care of business.

We emerge into a dusky September night, the sky a smear of violet and orange and smog. I walk to the stands, shake hands with a few fans, sign a few more autographs before practicing. There are four practice courts, and James knows I want the one farthest from the crowd, so Darren and I can have a little privacy as we hit and talk strategy.

I groan as I guide the first backhand up the line to Darren’s forehand.

Don’t hit that shot tonight, he says. Baghdatis will hurt you with that.

Really?

Trust me, mate.

And you say he moves well?

Yes, quite well.

We hit for twenty-eight minutes. I don’t know why I notice these details—the length of an afternoon shower, the duration of a practice session, the color of James’s shirt. I don’t want to notice, but I do, all the time, and then I remember forever. My memory isn’t like my tennis bag; I have no say over its contents. Everything goes in, and nothing ever seems to come out.

My back feels OK. Normal stiffness, but the excruciating pain is gone. The cortisone is working. I feel good—though, of course, the definition of good has evolved in recent years. Still, I feel better than I did when I opened my eyes this morning, when I thought of forfeiting. I might be able to do this. Of course tomorrow there will be severe physical consequences, but I can’t dwell on tomorrow any more than I can dwell on yesterday.

Back inside the locker room I pull off my sweaty clothes and jump in the shower. My third shower of the day is short, utilitarian. No time for coaching or crying. I slip on dry shorts, a T-shirt, put my feet up in the training room. I drink more Gil Water, as much as I can hold, because it’s six thirty, and the match is nearly one hour off.

There is a TV above the training table, and I try to watch the news. I can’t. I walk down to the offices and look in on the secretaries and officials of the U.S. Open. They’re busy. They don’t have time to talk. I step through a small door. Stefanie and the children have arrived. They’re in a little playground outside the locker room. Jaden and Jaz are taking turns on the plastic slide. Stefanie is grateful, I can tell, to have the children here for distraction. She’s more keyed up than I. She looks almost irritated. Her frown says, This thing should have started already! Come on! I love the way my wife spoils for a fight.

I talk to her and the children for a few minutes, but I can’t hear a word they’re saying. My mind is far away. Stefanie sees. She feels. You don’t win twenty-two Grand Slams without a highly developed intuition. Besides, she was the same way before her matches. She sends me back into the locker room: Go. We’ll be here. Do what you need to do.

She won’t watch the match from ground level. It’s too close for her. She’ll stay in a skybox with the children, alternately pacing, praying, and covering her eyes.

PERE, ONE OF the senior trainers, walks in. I can tell which of his trays is for me: the one with the two giant foam donuts and two dozen precut strips of tape. I lie on one of six training tables, and Pere sits at my feet. A messy business, getting these dogs ready for war, so he puts a trash can under them. I like that Pere is tidy, meticulous, the Roman of calluses. First he takes a long Q-tip and applies an inky goo that makes my skin sticky, my instep purple. There’s no washing off that ink. My instep hasn’t been ink-free since Reagan was president. Now Pere sprays on skin toughener. He lets that dry, then taps a foam donut onto each callus. Next come the strips of tape, which are like rice paper. They instantly become part of my skin. He wraps each big toe until it’s the size of a sparkplug. Finally he tapes the bottoms of my feet. He knows my pressure points, where I land, where I need extra layers of padding.

I thank him, put on my shoes, unlaced. Now, as everything begins to slow down, the volume goes up. Moments ago the stadium was quiet, now it’s beyond loud. The air is filled with a buzzing, a humming, the sound of fans rushing to their seats, hurrying to get settled, because they don’t want to miss a minute of what’s coming.

I stand, shake out my legs.

I won’t sit again.

I try a jog down the hall. Not bad. The back is holding. All systems go.

Across the locker room I see Baghdatis. He’s suited up, fussing with his hair in front of a mirror. He’s flicking it, combing it, pulling it back. Wow, he has a lot of hair. Now he’s positioning his headband, a white Cochise wrap. He gets it perfect, then gives one last tug on his ponytail. A decidedly more glamorous pre-match ritual than cushioning your toe calluses. I remember my hair issues early in my career. For a moment I feel jealous. I miss my hair. Then I run a hand over my bare scalp and feel grateful that, with all the things I’m worried about right now, hair isn’t one of them.

Baghdatis begins stretching, bending at the waist. He stands on one leg and pulls one knee to his chest. Nothing is quite so unsettling as watching your opponent do pilates, yoga, and tai chi when you can’t so much as curtsy. He now maneuvers his hips in ways I haven’t dared since I was seven.

And yet he’s doing too much. He’s antsy. I can almost hear his central nervous system, a sound like the buzz of the stadium. I watch the interaction between him and his coaches, and they’re antsy too. Their faces, their body language, their coloring, everything tells me they know they’re in for a street fight, and they’re not sure they want it. I always like my opponent and his team to show nervous energy. A good omen, but also a sign of respect.

Baghdatis sees me and smiles. I remember that he smiles when he’s happy or nervous, and you can never tell which. Again, it reminds me of someone, and I can’t think who.

I raise a hand. Good luck.

He raises a hand. We who are about to die…

I duck into the tunnel for one last word with Gil, who’s staked out a corner where he can be alone but still keep an eye on everything. He puts his arms around me, tells me he loves me, he’s proud of me. I find Stefanie and give her one last kiss. She’s bobbing, weaving, stomping her feet. She’d give anything to slip on a skirt, grab a racket, and join me out there. My pugnacious bride. She tries a smile but it ends up a wince. I see in her face everything she wants to say but will not let herself say. I hear every word she refuses to utter: Enjoy, savor, take it all in, notice each fleeting detail, because this could be it, and even though you hate tennis, you might just miss it after tonight.

This is what she wants to say, but instead she kisses me and says what she always says before I go out there, the thing I’ve come to count on like air and sleep and Gil Water.

Go kick some butt.

AN OFFICIAL OF THE U.S. OPEN, wearing a suit and carrying a walkie-talkie as long as my forearm, approaches. He seems to be in charge of network coverage and on-court security. He seems to be in charge of everything, including arrivals and departures at LaGuardia. Five minutes, he says.

I turn to someone and ask, What time is it?

Go time, they say.

No. I mean, what time? Is it seven thirty? Seven twenty? I don’t know, and it suddenly feels important. But there are no clocks.

Darren and I turn to each other. His Adam’s apple goes up and down.

Mate, he says, your homework is done. You’re ready.

I nod.

He holds out his fist for a bump. Just one bump, because that’s what we did before my first-round win earlier this week. We’re both superstitious, so however we start a tournament, that’s how we finish. I stare at Darren’s fist, give it one decisive bump, but don’t dare lift my gaze and make eye contact. I know Darren is tearing up, and I know what that sight will do to me.

Last things: I lace up my shoes. I tape my wrist. I always tape my own wrist, ever since my injury in 1993. I tie my shoes.

Please let this be over.

I’m not ready for it to be over.

Mr. Agassi, it’s time.

I’m ready.

I walk into the tunnel, three steps behind Baghdatis, James again leading the way. We stop, wait for a signal. The buzzing sound all around us becomes louder. The tunnel is meat-locker cold. I know this tunnel as well as I know the front foyer of my house, and yet tonight it feels about fifty degrees colder than usual and a football field longer. I look to the side. There along the walls are the familiar photos of former champions. Navratilova. Lendl. McEnroe. Stefanie. Me. The portraits are three feet tall and spaced evenly—too evenly. They’re like trees in a new suburban development. I tell myself: Stop noticing such things. Time to narrow your mind, the way the tunnel narrows your vision.

The head of security yells, OK, everyone, it’s showtime!

We walk.

By careful prearrangement, Baghdatis stays three paces ahead as we move toward the light. Suddenly a second light, a blinding ethereal light, is in our faces. A TV camera. A reporter asks Baghdatis how he feels. He says something I can’t hear.

Now the camera is closer to my face and the reporter is asking the same question.

Could be your last match ever, the reporter says. How does that make you feel?

I answer, no idea what I’m saying. But after years of practice I have a sense that I’m saying what he wants me to say, what I’m expected to say. Then I resume walking, on legs that don’t feel like my own.

The temperature rises dramatically as we near the door to the court. The buzzing is now deafening. Baghdatis bursts through first. He knows how much attention my retirement has been getting. He reads the papers. He expects to play the villain tonight. He thinks he’s prepared. I let him go, let him hear the buzzing turn to cheers. I let him think the crowd is cheering for both of us. Then I walk out. Now the cheers triple. Baghdatis turns and realizes the first cheer was for him, but this cheer is mine, all mine, which forces him to revise his expectations and reconsider what’s in store. Without hitting a single ball I’ve caused a major swing in his sense of well-being. A trick of the trade. An old-timer’s trick.

The crowd gets louder as we find our way to our chairs. It’s louder than I thought it would be, louder than I’ve ever heard it in New York. I keep my eyes lowered, let the noise wash over me. They love this moment; they love tennis. I wonder how they would feel if they knew my secret. I stare at the court. Always the most abnormal part of my life, the court is now the only space of normalcy in all this turmoil. The court, where I’ve felt so lonely and exposed, is where I now hope to find refuge from this emotional moment.

I CRUISE THROUGH THE FIRST SET, winning 6-4. The ball obeys my every command. So does my back. My body feels warm, liquid. Cortisone and adrenaline, working together. I win the second set, 6-4. I see the finish line.

In the third set I start to tire. I lose focus and control. Baghdatis, meanwhile, changes his game plan. He plays with desperation, a more powerful drug than cortisone. He starts to live in the now. He takes risks, and every risk pays off. The ball now disobeys me and conspires with him. It consistently bounces his way, which gives him confidence. I see the confidence shining from his eyes. His initial despair has turned to hope. No, anger. He doesn’t admire me anymore. He hates me, and I hate him, and now we’re sneering and snarling and trying to wrest this thing from each other. The crowd feeds on our anger, shrieking, pounding their feet after every point. They’re not clapping their hands as much as slapping them, and it all sounds primitive and tribal.

He wins the third set, 6-3.

I can do nothing to slow the Baghdatis onslaught. On the contrary, it’s getting worse. He’s twenty-one, after all, just warming up. He’s found his rhythm, his reason for being out here, his right to be here, whereas I’ve burned through my second wind and I’m painfully aware of the clock inside my body. I don’t want a fifth set. I can’t handle a fifth set. My mortality now a factor, I start to take my own risks. I grab a 4-0 lead. I’m up two service breaks, and again the finish line is within sight, within reach. I feel the magnetic force, pulling me.

Then I feel the other force pushing. Baghdatis starts to play his best tennis of the year. He just remembered he’s number eight in the world. He pulls triggers on shots I didn’t know he had in his repertoire. I’ve set a perilously high standard, but now he meets me there, and exceeds me. He breaks me to go 4-1. He holds serve to go 4-2.

Here comes the biggest game of the match. If I win this game, I retake command of this set and reestablish in his mind—and mine—that he was fortunate to get one break back. If I lose, it’s 4-3, and everything resets. Our night will begin again. Though we’ve bludgeoned each other for ten rounds, if I lose this game the fight will start over. We play at a furious pace. He goes for broke, holds nothing back—wins the game.

He’s going to take this set. He’ll die before he loses this set. I know it and he knows it and everyone in this stadium knows it. Twenty minutes ago I was two games from winning and advancing. I’m now on the brink of collapse.

He wins the set, 7-5.

The fifth set begins. I’m serving, shaking, unsure my body can hold out for another ten minutes, facing a kid who seems to be getting younger and stronger with every point. I tell myself, Do not let it end this way. Of all ways, not this way, not giving up a two-set lead. Baghdatis is talking to himself also, urging himself on. We ride a seesaw, a pendulum of high-energy points. He makes a mistake. I give it back. He digs in. I dig in deeper. I’m serving at deuce, and we play a frantic point that ends when he hits a backhand drop shot that I wing into the net. I scream at myself. Advantage Baghdatis. The first time I’ve trailed him all night.

Shake it off. Control what you can control, Andre.

I win the next point. Deuce again. Elation.

I give him the next point. Backhand into the net. Advantage Baghdatis. Depression.

He wins the next point also, wins the game, breaks to go up 1-0.

We walk to our chairs. I hear the crowd murmuring the first Agassi eulogies. I take a sip of Gil Water, feeling sorry for myself, feeling old. I look over at Baghdatis, wondering if he’s feeling cocky. Instead he’s asking a trainer to rub his legs. He’s asking for a medical time-out. His left quad is strained. He did that to me on a strained quad?

The crowd uses the lull in the action to chant. Let’s go, Andre! Let’s go, Andre! They start a wave. They hold up signs with my name.

Thanks for the memories, Andre!

This is Andre’s House.

At last Baghdatis is ready to go. His serve. Having just broken me to take the lead in the match, he should have a full head of steam. But instead the lull seems to have disrupted his rhythm. I break him. We’re back on serve.

For the next six games we each hold. Then, knotted at four-all, with me serving, we play a game that seems to last a week, one of the most taxing and unreal games of my career. We grunt like animals, hit like gladiators, his forehand, my backhand. Everyone in the stadium stops breathing. Even the wind stops. Flags go limp against the poles. At 40-30, Baghdatis hits a swift forehand that sweeps me out of position. I barely get there in time to put my racket on it. I sling the ball over the net—screaming in agony—and he hits another scorcher to my backhand. I scurry in the opposite direction—oh, my back!—and reach the ball just in time. But I’ve wrenched my spine. The spinal column is locked up and the nerves inside are keening. Goodbye, cortisone. Baghdatis hits a winner to the open court and as I watch it sail by I know that for the rest of this night my best effort is behind me. Whatever I do from this point on will be limited, compromised, borrowed against my future health and mobility.

I look across the net to see if Baghdatis has noticed my pain, but he’s hobbling. Hobbling? He’s cramping. He falls to the ground, grabbing his legs. He’s in more pain than I. I’ll take a congenital back condition over sudden leg cramps any day. As he writhes on the ground I realize: All I have to do is stay upright, move this goddamned ball around a little while longer, and let his cramps do their work.

I abandon all thought of subtlety and strategy. I say to myself, Fundamentals. When you play someone wounded, it’s about instinct and reaction. This will no longer be tennis, but a raw test of wills. No more jabs, no more feints, no more footwork. Nothing but roundhouses and haymakers.

Back on his feet, Baghdatis too has stopped strategizing, stopped thinking, which makes him more dangerous. I can no longer predict what he’ll do. He’s crazed with pain, and no one can predict crazy, least of all on a tennis court. At deuce, I miss my first serve, then give him a fat, juicy second serve, seventy-something miles an hour, on which he unloads. Winner. Advantage Baghdatis.

Shit. I slump forward. The guy can’t move, but he still crushes my serve?

Now, yet again, I’m one slender, skittish point away from falling behind 4-5, which will set up Baghdatis to serve for the match. I close my eyes. I miss my first serve again. I hit another tentative second serve just to get the point going and somehow he flubs an easy forehand. Deuce again.

When your mind and body teeter on the verge of all-out collapse, one easy point like that feels like a pardon from the governor. And yet, I nearly squander my pardon. I miss my first serve. I make my second and he returns it wide. Another gift. Advantage Agassi.

I’m one point from a commanding 5-4 lead. Baghdatis grimaces, bears down. He won’t yield. He wins the point. Deuce number three.

I promise myself that if I gain the advantage again, I won’t lose it.

By now Baghdatis isn’t merely cramping, he’s a cripple. Awaiting my serve, he’s fully bent over. I can’t believe he’s managing to stay on the court, let alone give me such a game. The guy has as much heart as he has hair. I feel for him, and at the same time tell myself to show him no mercy. I serve, he returns, and in my eagerness to hit to the open court, I hit far wide. Out. A choke. Clearly, a choke. Advantage Baghdatis.

He can’t capitalize, however. On the next point he hits a forehand several feet beyond the baseline. Deuce number four.

We have a long rally, ending when I drive a deep shot to his forehand that he misplays. Advantage Agassi. Again. I promised myself I wouldn’t waste this opportunity if it came around again, and here it is. But Baghdatis won’t let me keep the promise. He quickly wins the next point. Deuce number five.

We play an absurdly long point. Every ball he hits, moaning, catches a piece of the line. Every ball I hit, screaming, somehow clears the net. Forehand, backhand, trick shot, diving shot—then he hits a ball that nicks the baseline and takes a skittish sideways hop. I catch it on the rise and hit it twenty feet over him and the baseline. Advantage Baghdatis.

Stick to basics, Andre. Run him, run him. He’s gimpy, just make him move. I serve, he hits a vanilla return, I send him side to side until he yowls in pain and hits the ball into the net. Deuce number six.

While waiting for my next serve, Baghdatis is leaning on his racket, using it as an old man uses a walking stick. When I miss a first serve, however, he creeps forward, crablike, and with his walking stick he whacks my serve well beyond the reach of my forehand. Advantage Baghdatis.

His fourth break point of this game. I hit a timid first serve, so paltry, so meek, my seven-year-old self would have been ashamed, and yet Baghdatis hits a defensive return. I hit to his forehand. He nets. Deuce number seven.

I make another first serve. He gets a racket on it but can’t get it over the net. Advantage Agassi.

I’m serving again for the game. I recall my twice-broken promise. Here, one last chance. My back, however, is spasming. I can barely turn, let alone toss the ball and hit it 120 miles an hour. I miss my first serve, of course. I want to crush a second serve, be aggressive, but I can’t. Physically I cannot. I tell myself, Three-quarter kick, put the ball above his shoulder, make him go side to side until he pukes blood. Just don’t double-fault.

Easier said than done. The box is shrinking. I watch it gradually diminish in size. Can everyone else see what I’m seeing? The box is now the size of a playing card, so small that I’m not sure this ball would fit if I walked it over there and set it down. I toss the ball, hit an alligator-armed serve. Out. Of course. Double fault. Deuce number eight.

The crowd screams in disbelief.

I manage to make a first serve. Baghdatis hits a workmanlike return. With three-quarters of his court wide open, I punch the ball deep to his backhand, ten feet from him. He scampers toward it, waves his racket limply, can’t get there. Advantage Agassi.

On the twenty-second point of the game, after a brief rally, Baghdatis finally whips a backhand into the net. Game, Agassi.

During the changeover I watch Baghdatis sit. Big mistake. A young man’s mistake. Never sit when cramping. Never tell your body that it’s time to rest, then tell it, Just kidding! Your body is like the federal government. It says, Do anything you like, but when you get caught, don’t lie to me. So he’s not going to be able to serve. He’s not going to be able to get out of that chair.

And then he gets out and holds serve.

What’s keeping this man up?

Oh. Yes. Youth.

At 5-all, we play a stilted game. He makes a mistake, goes for the knockout. I counterpunch and win. I lead, 6-5.

His serve. He goes up 40-15. He’s one point from pushing this match to a tiebreaker.

I fight him to deuce.

Then I win the next point, and now I have match point.

A quick, vicious exchange. He hits a wild forehand, and as it leaves his strings I know it’s out. I know I’ve won this match, and at the same moment I know that I wouldn’t have had energy for one more swing.

I meet Baghdatis at the net, take his hand, which is trembling, and hurry off the court. I don’t dare stop. Must keep moving. I stagger through the tunnel, my bag slung over my left shoulder, feeling as if it’s slung over my right shoulder, because my whole body is twisted. By the time I reach the locker room I’m unable to walk. I’m unable to stand. I’m sinking to the floor. I’m on the ground. Darren and Gil arrive, slip my bag off my shoulder and lift me onto a table. Baghdatis’s people deposit him on the table next to me.

Darren, what’s wrong with me?

Lie down, mate. Stretch out.

I can’t, I can’t—

Where does it hurt? Is it a cramp?

No, it’s a constriction. I can’t breathe.

What?

I can’t—Darren, I can’t—breathe.

Darren is helping someone put ice on my body, raising my arms, calling for doctors. He’s begging me to reach, reach, stretch.

Just release, mate. Unclench. Your body is clenched. Just let go, mate, let go.

But I can’t. And that’s the whole problem, isn’t it? I can’t let go.

A KALEIDOSCOPE OF FACES appears above me. Gil, squeezing my arm, handing me a recovery drink. I love you, Gil. Stefanie, kissing me on the forehead and smiling—happy or nervous, I can’t tell. Oh, yes, of course, that’s where I’ve seen that smile before. A trainer, telling me the doctors are on the way. He turns on the TV above the table. Something to do while you wait, he says.

I try to watch. I hear moans to my left. I turn my head slowly and see Baghdatis on the next table. His team is working on him. They stretch his quad, his hamstring cramps. They stretch his hamstring, his quad cramps. He tries to lie flat, his groin cramps. He curls into a ball and begs them to leave him be. Everyone clears out of the locker room. It’s just the two of us. I turn back to the TV.

Moments later something makes me turn back to Baghdatis. He’s smiling at me. Happy or nervous? Maybe both. I smile back.

I hear my name coming from the TV. I turn my head. Highlights from the match. The first two sets, so misleadingly easy. The third, Baghdatis starting to believe. The fourth, a knife fight. The fifth, the never-ending ninth game. Some of the best tennis I’ve ever played. Some of the best I’ve ever seen. The commentator calls it a classic.

In my peripheral vision I detect slight movement. I turn to see Baghdatis extending his hand. His face says, We did that. I reach out, take his hand, and we remain this way, holding hands, as the TV flickers with scenes of our savage battle.

At last I let my mind go where it’s wanted to go. I can’t stop it anymore. No longer asking politely, my mind is now forcibly spinning me into the past. And because my mind notes and records the slightest details, I see everything with bright, startling clarity, every setback, victory, rivalry, tantrum, paycheck, girlfriend, betrayal, reporter, wife, child, outfit, fan letter, grudge match, and crying jag. As if a second TV above me were showing highlights from the last twenty-nine years, it all flies past in a high-def whirl.

People often ask what it’s like, this tennis life, and I can never think how to describe it. But that word comes closest. More than anything else, it’s a wrenching, thrilling, horrible, astonishing whirl. It even exerts a faint centrifugal force, which I’ve spent three decades fighting. Now, lying on my back under Arthur Ashe Stadium, holding hands with a vanquished opponent and waiting for someone to come help us, I do the only thing I can do. I stop fighting it. I just close my eyes and watch.