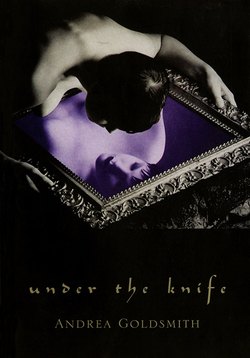

Читать книгу Under the Knife - Andrea Goldsmith - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеA life, so long in the making, can explode in an instant. Career, family, lover, a status that should have endured forever, all obliterated, and Alexander Otto vanishes in a mess of scandal and shame.

And who does he blame? Edwina Frye, as surely as if she’d shoved a gun in his hand, crooked his arm, and put his finger on the trigger. Edwina Frye, who ransacked his heart with her sweet giddy touch over and over again. She listened to him for hours on end, collecting his life and putting it in order, and all the while he was falling in love she was plotting his fall.

Stripped to the waist, Alexander is standing before the bathroom mirror, a razor in his hand. He closes his eyes, he cannot bear the sight of himself. But there will be no relief, for springing out of the dark is Edwina, her face poised above his, their bodies still humid with sex, her breath a cool hit on his sweaty skin.

‘I’ve got you, Alexander,’ she said. ‘I’ve got you, because I know who you are.’ And with these words from neither biographer nor lover, he knew she must hate him.

Later he may wonder if he’d made a mistake, later he might regret not dragging the truth out of her — What do you know? What exactly do you know? — but with so little time and fear already at his throat, he thought only the worst and had to escape.

‘I’ve got you, Alexander,’ she said, before sliding off him and leaving the room. He heard the flush of the toilet, the water in the shower, heard her singing her triumph while he lay in his stink on her bed. But he hadn’t worked so hard nor achieved so much to go down without a fight. And mopped his sweat with her sheet, pulled on his trousers and went to her study.

He searched for nothing other than what he needed to see. He glanced at the biography but no longer cared. And the stack of tapes, all those hours of handing his life over to her. And the medical books and journals, she had no right to them now but neither could he reclaim what once was his. He rifled through her papers, found nothing unexpected, and then to her desk. The top drawer was crammed with the usual desk junk, the second drawer held neat stacks of stationery. Then, in the third drawer, he found what he had hoped did not exist. It was not the official biography, not this pile of pink paper with her scrawl in blue ink, not the biography but still all about him. He fanned the pages, not reading, but sufficient to see the accusing names.

Condemned now, and only wanting to escape, he is dressed when she returns to the bedroom. He doesn’t want to look at her, doesn’t want to see the white breasts, the glint of water in the blazing hair, gives a hasty explanation, would prefer not to speak at all, kisses her blindly and leaves while there is still time.

Then the interminable night. The late meal at home with his wife, and how he manages to be himself when his usual self has deserted him, when the fool who remains would still forgive Edwina if only she will love him forever. Or less. A year with Edwina and he wouldn’t want for anything. Cynthia says he’s working too hard, she suggests they take a holiday. He nods and smiles, but he is not listening, and when she proposes a walk, allows himself to be led. He hides in the dark, feels Cynthia against him, kind and loving Cynthia chatting about their holiday, while his thoughts are grabbing at Edwina who slit him open and pulled out his guts. He winces. ‘Are you cold?’ asks Cynthia. No, not cold, just disintegrating.

The movement through the dark streets is soothing. He holds on to Cynthia, his sanctuary for twenty-five years, pulls her closer and shakes off Edwina. Think, think, he tells himself, remember who you are. And by the time they return home has planned what must be done. Cynthia goes to bed and he to his study. His draft of the biography sits on the desk, a note from Edwina still attached. The note he folds into his wallet, the biography — And suddenly he wants to murder it, his carefully crafted life, he should have known better, should never have agreed to it. And rising from the deep, an old revengeful anger, and in his hand a penknife and stabbing at the paper. He wants to cry but doesn’t know how, so keeps on pummelling, trying to gouge the love out. The knife breaks, his anger misplaced, but where else can it go? He sits at the desk, his head in his hands, his breath pulling in short, bitter jabs. It’s not fair, he is saying. But no one is listening nor would anyone agree.

He hears Claire come home, far too late for a school night. He doesn’t want to talk to her, couldn’t bear her black gaze. Like Edwina, she sees far too much. They all do — Edwina, Cynthia, Simone and Claire, dead Rosie, even Sybil forgotten for thirty years and now sticking her lanky neck out of memory; why is it that the wrong ones have loved him? Has he always wanted what he couldn’t have? And what sort of man would he be if he only desired what was in reach? Feet of clay that’s what he’d need, but was born with wings. So use them now, Alexander, and fly away.

But first the long night and Edwina Frye in charge, a ringmaster with a whip of pink paper, cracking lashes in blue ink. She brings in the acts. First his mother, followed by Rosie, then Sybil and loyal Cynthia, and finally his daughters, Simone so like her mother and Claire who resembles no one. And all the while he’s watching from the shadows, wanting to wipe his hands of the past.

He rouses himself and goes to bed. Cynthia snuffles and curls against him. He shuts his eyes but the show goes on, Edwina cracking her whip, and the others dragging him from the shadows and chanting his guilt. Cheat! they cry. Liar! And the charge he cannot bear to hear. By the time dawn approaches he hardly knows himself.

He rises, careful not to disturb Cynthia, washes, dresses and leaves the house. Only in the car does it occur to him he may never see his family again, may never see his daughters with families of their own. He can’t have lost them forever; Edwina brought him to his knees, but there is life in him yet. He phones his secretary at home, tells her to cancel his appointments, a mix-up in his calendar, he says, and not her fault. Her voice raised in defence turns quiet. She doesn’t believe him, she sets his schedule, she thinks she knows everything about him. But she doesn’t. He cuts her off, and with an hour to fill before Claire and Cynthia leave the house, drives towards the bay. It will be the last time and he doesn’t need to resist any more.

It is a limp, grey day; he feels as ragged as the last leaves on the trees. And a chill breeze, it’s in the car, it’s in his bones, he adjusts the thermostat but it makes no difference: the temperature of loss, and it is always cold. He drives to his usual spot, a small intersection near Edwina’s flat, and parks where he can watch unobserved. A few minutes later the door to her balcony opens, at the same time the sun breaks through. She is glistening emerald green in her bathrobe, a halo around the marvellous hair. She leans on the balustrade and sips her coffee. And he knows why he loves her, seeing her like this, lush and silent and with him out of the picture.

He never did anything to harm her. He presented himself whole and with a surgeon’s precision she picked off the pieces. He hates her for what she has made him, but far worse, he hates himself. And still he doesn’t understand how she could have known. She is standing on her balcony gazing towards the bay; there is no malice in her when her guard is down. Perhaps she doesn’t realise what she has done.

She turns to go inside and his heart lurches. How much more of a fool can he be? His fists are pressed hard to his temples. He’s had enough, he wants his old life back, all of it with no Edwina cracking the whip, no Edwina writing the script. He wants her out of his life, he wishes he had never met her. He starts the car, drives down the beach road, parks in a skid of tyres, leaps the wall, lands heavily in the sand. He strides towards the water, and over the squall he shouts and shouts:

‘Bitch! Bitch! Leave me alone bitch!’ Louder and louder, cutting the air and striking the waves.

He only did what any man would have done, he trusted her, fool that he was, yet could not have guessed. But the bitch won’t get the better of him. He remembers when he didn’t love her, remembers when he didn’t even know her. He let her into his life and now he’ll get rid of her. She didn’t love him, will never love him, which is all the more reason not to pay with his life. She’s a bitch, a cold-hearted bitch, but must have her secrets too. His secrets for hers, a fair exchange.

He arrives back at the house pumped up and wronged. The place is newly empty; the kettle in the kitchen is still warm and Cynthia’s perfume lingers in the bedroom. He undresses and packs as if for a short holiday. To the study and a selection of work into a brief-case, then a change of mind and back to the bedroom for a larger case and two more suits. He sits on the edge of the bed and writes to Cynthia — Something has come up. I have to go away. No need to worry, I’ll be in touch. Love you always, A — and rests the note against the telephone. Then to the bathroom, his face reflected in the mirror, and now Edwina’s face and her terrible words: ‘I’ve got you, Alexander, because I know who you are.’ He takes razor and shaving cream, the scraping noise, his beard catching in the blade, the bristles on the white porcelain. He stares down at the basin, and now he is crying, ugly sound it is.

He washes his face, avoiding the clean-shaven image in the mirror, then returns to the bedroom and finishes dressing. Slowly he walks through the house, room by room, looking, touching, arming himself against future longing. He slips a photograph of the family into his brief-case, gathers his luggage, leaves the house and disappears.