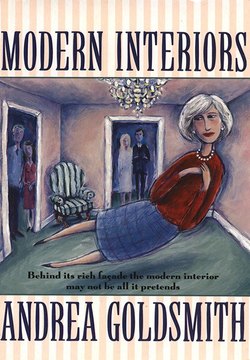

Читать книгу Modern Interiors - Andrea Goldsmith - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеAfter a meal of rare roast beef, potatoes au gratin and green beans, George Finemore poured himself a Scotch, settled in front of the television and died. A premature death on a wet June night – although tidy enough, the doctor said, diagnosing a massive and efficient stroke. But tidy or not, it was clearly too much for his wife. Philippa Finemore, formerly so dignified, changed overnight; and while a husband’s death is a terrible thing, Philippa’s reaction was judged as extreme, even perverse, and quite unacceptable for a woman with position to maintain and name to consider.

People tried to be kind. Eccentric, they called her, Philippa Finemore has become quite eccentric since George’s passing. But in private mutterings they mentioned senility, in crackling whispers they said she had lost her mind.

‘Crazy. Mother’s gone crazy.’ It was Melanie Pryor who was speaking, and she was definitely not whispering. ‘I simply don’t know what’s got into her, and if she’s like this now, just a few months after Dad’s death, what can we expect in a few years time!’

Evelyn Finemore, Melanie’s sister-in-law, sat shaking her head. What indeed? And, for the first time since marrying Gray, was grateful for her own utterly ordinary parents, such dismally genteel people whom she knew would never cause embarrassment.

‘And we thought Dad would be the one to crumble if Mother went first.’ Melanie clenched her jaws and tightened her fists. ‘She used to be so dependable, now it’s as if none of us existed.’

Evelyn agreed. Philippa had lost her senses, and, along with them, any thought for the family. Her behaviour had been atrocious, beginning with the trip to Japan less than a month after George’s death. George had refused to visit Japan; nothing to do with the war, he said, rather he disapproved of the Japanese attitude to alcohol. Surely there was more to a nation than the drinking habits of its people, Philippa had protested, to which George Finemore, managing director of Finemore’s Fine Wines and Spirits, had replied, that to know a man’s drinking habits was to know his character. But with George dead, there was nothing to stop Philippa from going to Japan. So off she went, and while that had been bad enough so soon after the funeral, it was her going with Lorraine Pascoe, head of Finemore’s retail division and George’s long-time mistress, that was truly indelicate. Then, on her return, she had resigned her voluntary work at the nursing home (too close for comfort, she said), taken up yoga and joined Friends of the Earth. The Mercedes had developed a farrago of stickers advertising her new interests: ONE NUCLEAR BOMB CAN SPOIL YOUR WHOLE DAY, THE AMAZON FORESTS ARE THE WOMB OF THE EARTH, and, worst of all, SAVE A GAY WHALE FOR CHRIST.

‘You can’t have that on your car!’ Melanie protested.

‘Be sensible,’ Gray pleaded.

Only Jeremy, the second son and middle child, approved, and not merely of the gay whales but of his mother’s whole new orientation; but, unfortunately, Jeremy carried little weight in the family circle.

Even Philippa’s conversation changed. Suddenly she seemed more interested in fluorocarbons than family, in the homeless rather than her own hearth, and when the Society for the Handicapped approached her for the three dozen aprons she always made for their annual fête she politely refused. Of course, they said, they understood, her terrible loss . . . But it was not her terrible loss, she said, rather her priorities had changed and aprons no longer claimed favoured status. The charity work went, the lunch parties ceased, and so, too, the nice little biscuits long associated with Philippa Finemore’s home. Now, when the grandchildren asked for a snack they were given biscuits from a packet. Melanie was not impressed and said as much. Philippa explained again that her priorities had changed; besides, she had never liked all those sweet things.

‘But we did,’ Melanie said.

‘Good darling, I’ll give you the recipes.’

And so she did.

But in the light of her latest aberration all the previous ones were as leaves in a storm. Exactly five months after George Finemore’s death, Philippa announced she was leaving home.

‘Leaving home! A woman her age!’ Melanie helped herself to the coffee pot and another piece of Evelyn’s home-made almond bread. ‘Leaving our home, the place where we grew up, for an inner-city hovel where no one in their right mind would live!’ Melanie paused for a mouthful, patted her lips with an embroidered napkin, breathed deeply and began again. ‘She has a responsibility, and I don’t mean just to us, although that’s not irrelevant, she has a social responsibility. She’s not just anyone, people look to her, to people like her to show an example.’

What Melanie meant, but considered it in poor taste to say, was that wealth brings responsibilities, wealth sets one apart, and there could be no doubt that Philippa was very well off. Both Melanie and her brother Gray had been pleasantly surprised at the reading of the will to discover their father had been an extremely wealthy man. Melanie’s husband, Selwyn, had looked similarly surprised, although he was, in fact, the only member of the family to know the exact extent of George Finemore’s fortune. Indeed, Selwyn Pryor had acquainted himself with George’s worth more than fifteen years before when evaluating Melanie’s credentials as a future wife, and ever since had maintained a careful watch over his inheritance. Selwyn knew the value of Finemore’s Fine Wines and Spirits, and a fine business it was, knew too, of George’s investments in prime real estate – only a dozen properties but all very prime. Selwyn knew it all, had known all along.

‘A responsibility,’ Melanie was saying to her sister-in-law, ‘and her present behaviour is simply unacceptable.’

Evelyn went into the kitchen to make fresh coffee. She felt very sorry for the family and hoped she was managing to show it. Hers was a passionless, inert sort of face – she was too self-conscious to show very much – and while Melanie had been talking, Evelyn had tried to mould her features into expressions of sympathy: to purse the mouth, frown, raise the eyebrows at the nose end only, and while the tiny facial muscles were among the body’s most recalcitrant, the fact that Melanie was still sitting in Evelyn’s lounge room, suggested that the concern Evelyn felt had percolated through her naturally bland features. And feel it she did. Philippa was disrupting the family; Melanie was distraught and irritable, Gray was short-tempered, and unless something were done soon, there would be one of those dreadful Finemore family dinners seething with silent accusations and Jeremy would be there and he always made Evelyn feel so uncomfortable.

‘So what’s to be done,’ she said, as she took up her place on the leather two-seater. ‘We can’t forbid Philippa to leave home, it’s her money after all.’

‘Personally, I think she’s certifiable, but that would mean an awful fuss.’ Melanie watched Evelyn pour the coffee. ‘Just half for me, I’m trying to cut down.’

‘Oh?’

‘Wrinkles. I heard somewhere that caffeine causes wrinkles.’

‘Are you sure you don’t mean nicotine?’

‘Of course I’m sure. If it had been nicotine I wouldn’t have bothered to listen.’ She paused for another bite of almond bread. ‘We have to be firm with Mother, give her guidance. We mustn’t forget she’s used to Dad making all her decisions, so it’s not surprising she’s floundering now.’

‘Do you think this might only be a passing phase?’

Melanie shook her head.

‘A short-term reaction to your father’s death?’

Melanie shook her head again.

‘Perhaps she just needs to spread her wings a bit and then she’ll return to her old self.’

‘No, Evelyn,’ Melanie said. ‘Mother’s had five months of spreading her wings, and now it’s time she was brought back to the nest. It’s time for her to settle down.’

Philippa Finemore had no intention of settling down. She had been settled for the forty years of her marriage and was now ready for a change. Not that George had been a bad husband, but as the years passed, Philippa found she had little need of him, and as the children grew, she had little need for them either. As children that is. She had tried to steer them into realms more interesting than the usual mother-child relationship, but her children had resisted, preferring she remain exclusively in the maternal role – with the exception of Jeremy, always the exception of Jeremy. But now, by her calculation, with only twenty good years left, she wanted more than mothering, more than grandmothering too, and was determined to begin anew.

The need for change, while lurking for some time, had emerged clearly on the day of George’s funeral. After the cemetery, family and friends had returned to the Finemore home to drink to his memory. Philippa had managed to escape solicitous pats and sympathetic sighs and was standing on the landing at the top of the stairs watching the crowd of chattering mourners below. Her thoughts were of George as she watched his friends in his house drinking his liquour recounting his stories. How he would have loved this! And the very fact of his absence at a gathering of his friends marked his death more forcibly than the sprawling emptiness of his reclining armchair, the brazenness of the coffin, the dirge of a service and the hole in the ground. Here was a party in George’s own home and George was not playing convivial host, so George must be dead.

George would not have been happy dying so young. Such a lively man with so many plans, Philippa was sorry he would have to miss out. But she was not sorry for the loss of a husband. Theirs had been a marriage frayed by familiarity, a faded relationship with occasional patches of brilliance; but like an old neglected tapestry, patches of brilliance cannot reclaim the parts already lost. And lost they were, long before George’s death. It wasn’t his women or his devotion to football, it wasn’t even his long absences from home, rather it was his indifference to everything that was important to her, and consequently his indifference to her. He was kind and generous as men of his ilk were, and polite and sociable, but he regarded his wife as he would a pretty bird, and talked with her only to hear the sound of his own voice; if ever he noticed she needed a little air to breathe, a little music to sing by, he did nothing about it. So she pared her desires back, stripped them down until their original colours were faded even in memory; but while they became distinctly threadbare, she never discarded them. Under the dust of years they lay, years of doing the same things, seeing the same people, years when the passing seasons did little more than change her clothes, her hairstyle, inject new words into her conversation and remove some of the old, and still the ambitions lay quietly, and a small voice insisted there was still time. And at twenty there was still time, similarly at thirty, even forty and fifty, but at sixty-one, time is on its knees, and, in a burst of impatience, the dust of years is brushed away to reveal, still fresh and buoyant, the expectations and desires of a hopeful youth.

Which was not to suggest her marriage had been unsatisfactory, or, for that matter, unusual. It had been calm, George hadn’t interfered, he had been a good provider. It was the repetition that had been so trying, the long days gripped by habit. And while there had been occasions when she waved a hand in protest, the movement was always small and the direction invariably ambiguous. She seemed to lack the courage to protest with conviction until now, as if George’s passing had given her the strength to make her own move; or perhaps it was more simple, that, with George’s bulk no longer obstructing the view, Philippa could better plot the way ahead. There were things she would miss, his boisterous laugh, the powder on the bathroom floor, but overall, the passing of the marriage was long overdue, it was just a shame it had taken George’s death to bring it about.

She felt herself smile, so many possibilities, so much to look forward to, and then, just as quickly, the smile vanished as Lorraine Pascoe’s neat figure entered her field of vision. If anyone had lost a husband it was Lorraine.

Philippa had known about George and Lorraine ever since a dinner party about fifteen years before, when she had stooped to retrieve a piece of nineteenth-century silverware from beneath the table, and had seen Lorraine’s hand kneading George’s thigh. Kneading his thigh but precariously close to other parts. Philippa had never minded about Lorraine, indeed, disinterest in sex coupled with enjoyment of Lorraine’s company meant the affair quite suited her. But not so George’s other secrets, those heavy silences that occasioned a surprise gift – jewellery, a leather handbag, once even a new car-offered with a smile twitching over his great blond face and apologies clotting in his throat. At such times, Philippa would wonder at the secrets that could render him so coy. In the early days, she had interpreted the gifts as expressions of love, but it was not long before she realized that for men like George, gifts were nothing more than prettily-packaged apologies or anodynes for guilt. For men like George, love of a wife was implied, unspoken, axiomatic; love was caught in the emblems of marriage, in the shared house, the sons and daughters, the family breakfasts.

It might have been different for Lorraine, perhaps in the absence of marriage and its accoutrements, George had affirmed his love. And if so, how much worse for her now he was gone. Philippa wondered whether she would stay on at Finemore’s. An unofficial visit from the family lawyer the previous evening ‘to save Philippa any embarrassment at the reading of the will,’ revealed that Lorraine Pascoe would not need to work. George had bequeathed to her one of his real estate holdings, a warehouse, and the first piece of property he had ever bought; it yielded a sizeable rent and a more than comfortable living. While Philippa registered her relief that George had done the right thing by Lorraine, the lawyer was apologizing for bearing such distressing news. George had rejected all his suggestions of how best, and discreetly, to provide for Miss Pascoe; Tour husband refused to listen,’ the lawyer kept saying, ‘he simply wouldn’t listen.’ Philippa had patted the poor man’s arm, poured him a short brandy and finally shown him the door. As for George, Philippa recognized that the manner of the bequest was his way of acknowledging that Philippa had known about Lorraine all along, and that he had appreciated her tolerance and forebearance. Always a stickler for propriety was George, a man who wouldn’t have wanted to leave any loose ends, any favours owing. Again, she looked at the trim figure of Lorraine Pascoe and wondered how she would manage without George. Sensing the scrutiny, Lorraine looked up to the landing and smiled, an open, warm smile, and returned to her discussion.

A burst of laughter arose from a group near the den. Philippa saw Selwyn Pryor standing with a few of his friends; Melanie, too, was part of the group, her large features carefully monitored even while joining in with the laughter. Melanie had inherited her father’s appearance, although, unlike George, would never capitulate to fat. She was tall and strong-framed, with a broad face and abundant mouth, a big woman who strove to convert her handsome features to petite femininity. And she was, in large part, successful. But in rare moments of spontaneity, she would throw back her head and open the large mouth and utter a joyous bellow that did her father proud. As a large woman she was extremely attractive, but as a large woman trying to shrink there was less to please the eye. Indeed, to someone like Philippa who was small and olive-skinned, with dark hair and almost black eyes, the large blond features of her daughter were something of which to be proud.

Philippa watched as Selwyn took a bottle from the sideboard and refilled his friends’ glasses. Throughout the exercise he did not stop talking; he chewed his words and spat them out, and with a mouth so muscular and a neck so anguine he had a distinct advantage over most other people. Philippa had never liked her son-in-law and was convinced that with a different man Melanie would have blossomed. Instead, since her marriage, the bright, outgoing girl had become a mask of social convention. Melanie responded to the dictates of fashion; she believed the current beliefs, purloined from the editorial of the daily newspaper, and was horrified at the latest horror campaigns – drug abuse last year, child abuse this; she did aerobics when aerobics were the rage and was now devoted to power walking; she wore her hair short three years ago, but shoulder-length today. Melanie seemed devoid of any interior and Philippa laid the blame squarely at the feet of her son-in-law. George had seen it differently. Selwyn Pryor was an astute businessman with the ability to transform an ordinary business into something special. Selwyn Pryor, said George, had the makings of a rich man.

‘But surely there’s more to a man than making money,’ Philippa had said.

Of course there was, George had replied. Hadn’t Selwyn already proved himself as an academic? And hadn’t he been offered the safest conservative seat in the country? Selwyn Pryor could do anything, George said, but he’d chosen business, he’d chosen Finemore’s. Not that Philippa needed any reminding, for it was clear to her that business, or rather making money, had long been Selwyn’s major interest. George said she was too hard on her son-in-law, that creative flare in business suggested other virtues that would, in time, reveal themselves. But they had not. Selwyn’s was a personality of stucco, impressive enough, but hard and superficial; he was a man bereft of positive qualities, or so it seemed to Philippa. Others regarded him differently; even now, at his father-in-law’s funeral, he had a solid following; his friends were gathered around, content to let him talk, laughing when required, apparently happy to be included in his circle. People found him handsome, but not Philippa, he was too tall and angular, and his thick brown hair was styled too self-consciously and his nails manicured too carefully, and despite shaving twice a day, the beard always got the better of him. Then there were the silly blue eyes, Selwyn’s major vanity, two bright blue blisters set at the bridge of his proudly patrician nose. The appearance fitted the man, Philippa had long ago decided: he was driven by self-interest and looked the part.

It occurred to her that with George now gone, Selwyn’s self-interest would gain momentum. Not that George had ever deliberately confined him, but the fact of George’s running a large business he had built from nothing, had placed clear limits on Selwyn’s ambitions. No such restrictions remained now. Immediately, Philippa’s thoughts turned to her oldest child: poor Gray, it would not be easy for him. Gray took a doctrinaire approach to life; long after Selwyn had raided the tomb and disposed of the loot, Gray would still be planning his strategy. As George used to say: Gray would make a living but Selwyn would make a fortune.

She found Gray in the crowd and was pleased to see him with Finemore’s personnel manager. Not that a father’s funeral was an appropriate place to do business, but times ahead would be tough for Gray. Like Melanie, Gray had inherited his father’s appearance, but something had gone awry. He was tall, over six feet, but the shoulders were too narrow and the paunch too prominent; the blond hair was nondescript sandy, and the eyes were pale and limpid within a large pink face. He was thirty-nine, but had looked the same at twenty and would probably be no different at fifty. Except for the moustache. This narrow strip of vanity was the sort of decoration that required constant and delicate care, a moustache that was less a moustache and more a statement of character. Philippa had begged him to shave it off when it first appeared some five years ago and still hoped for its removal, but, so far, Gray had remained firm.

And that was Gray, firm and solid, although a deficit in natural ability did not make him always reliable. Not that he was aware of any such deficit; Gray had an opinion about most things and was not shy in giving it. Like his brother-in-law, Gray was saddled with a bulky arrogance and a driving ambition, although was quieter about both than Selwyn. Gray was also entirely without humour which merely added ponderousness to pomposity. He would have made an exemplary Victorian, Philippa had often thought, but as a man of the late twentieth century he tended to try one’s patience. Children complain about having no choice in their parents, but parents don’t choose their children either, and can be extremely surprised at what they’ve produced. Philippa had never told anyone of the disappointment in her oldest child. It was not that she didn’t love him – what mother doesn’t love her children? – but Gray’s bloated sense of his own importance made him disinterested in others and insensitive to their needs.

She watched as Gray shook hands with the personnel manager and moved off towards the bar. The crowd seemed to be swelling, although, as a liquor merchant’s wife, she was well-acquainted with the effects of free-flowing alcohol, the raised voices, the exaggerated gestures, people occupying more space. Death’s a party, Philippa thought, what a shame George had to miss it. As for Philippa, she wished they would all leave; after forty years with George and four crowded days preparing for his burial, she wanted to slip off her navy blue wool dress, wanted to let down her hair (wanted, in truth, to cut it off, the whole greying auburn mass that George had liked so much, despite having not touched it in years), remove her makeup, the stiletto shoes, the stockings, and sit quietly by herself in the empty house. After that, the years stretched ahead, empty of obligation and rich with dreams. She smiled at the thought and noticed Gina Ballantyne smiling back. A party, that was all. Gina had not spoken to George for months, not since George had commented on her facelift, in company, at a dinner party arranged by Gina and Barry to display her new face. George, usually so tolerant of his liquor, had drunk too much, or so he explained to Philippa afterwards, and out it had slipped: ‘Love your new face, Gina.’

Having a dinner party to celebrate your new face is one thing, acknowledging this is what you are doing is quite another; Gina would have liked to do George damage. What she did, however, from her position at the head of the table, was smile her new-look smile and respond with a brittle thank you. Everyone else fiddled with their food, except Barry Ballantyne, an old friend of George’s and a man devoted to his wife. ‘What a rude bastard you are George,’ he said. ‘You’re the last person to be casting aspersions at someone else’s appearance,’ and he puffed out his small man’s chest and blew up his cheeks in an imitation of George’s bulk.

Nothing to imitate now, Philippa thought, poor George’s bulk was being bloated by morbid gases and bountiful bacteria hungry for human flesh; as for Gina Ballantyne, she looked like a smiling cadaver. Her skin, so tight and smooth, appeared to be squeezing the substance from her; the skull so defined and the body pared back by exercise and diet was a welded sculpture of angles and joints.

Philippa would have to go downstairs soon and join them. She had learned over the past four days that a bereaved wife was permitted only limited time alone, too much was considered unhealthy. Even now, she saw Evelyn, her sweet, dull daughter-in-law, approach Melanie and whisper to her. The two of them looked up at Philippa, Melanie nodded and moved towards the stairs, while Evelyn collected another plate of savouries for the mourners. But Philippa was not ready to be collected, not yet. She left the landing and slipped into her bedroom and from there to the bathroom and closed the door. She heard Melanie’s ‘Are you all right, Mother?’ and replied with a cheery ‘I’ll be down shortly.’ She slipped off her shoes, loosened her belt and sat on the enamel lid of the toilet. George’s toilet. For that matter, George’s bathroom and George’s house. All of it now Philippa’s: the six bedrooms, the four bathrooms, the three large entertainment areas, the servants’ quarters, the clinker brick, the swimming pool, the tennis court, the terraced gardens. Yet somehow it jarred in a life without George, and as her gaze passed over the marble and gold of George’s bathroom, Philippa knew she would sell the lot.

Exactly five months later, soon after her sixty-second birthday, Philippa Finemore announced to Gray and Evelyn, Melanie and Selwyn, and her younger son Jeremy, that she was leaving home. It was a Friday night and they were lingering over coffee and port at the huge mahogany dining-table George had bought soon after he and Philippa were married. The grandchildren were either in the sitting-room watching television or asleep in the cots that Evelyn and Melanie kept in one of the spare bedrooms. Philippa passed the coffee pot around, waited for a lull in the conversation and made her announcement.

‘I’ve decided to sell the house.’

In the silence that followed, Jeremy smiled and reached for his mother’s hand, while the others looked to Gray for a response.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ he said. ‘If it’s help you’re needing we can easily organize that.’

‘Of course,’ said Evelyn, looking at her husband, ‘we’ll organize that. Melanie and I can do the shopping, and we’ll arrange for a cleaning service to help Julia with the housekeeping. And we can increase John Slowe’s hours in the garden, perhaps hire someone else for the lawns.’

Evelyn was clearly warming to the task, but it was not help that was on Philippa’s agenda, it was change. Selwyn leaned over and patted his mother-in-law’s knee.

‘Now Philippa, we know how difficult these past months have been, but what’s required is a little more time, a little more patience.’ And patted her knee again. Selwyn spoke in earnest; he had plans for the property, located as it was in a prime residential suburb and ideal for a substantial town house development. ‘You mustn’t rush into a decision you might later regret.’

‘Besides, it’s our home,’ Melanie continued, ‘you can’t sell our home.’ For Melanie, too, had plans. The house was just the right size and in just the right location for her own family. The house was Finemore property as far as she was concerned, and Philippa had no right to dispose of it.

‘Perhaps it’s only a passing phase,’ Evelyn suggested a few days later as she and Melanie sat in Evelyn’s lounge room drinking coffee and eating home-made almond bread.

But it was not. The auction notice went up, six weeks later the house was sold for a respectable 2.4 million and two months after that Philippa moved into a single-fronted Victorian terrace, fully renovated, only a short walk from the centre of Melbourne and a long drive from the rest of the family. Except Jeremy.

‘I think it’s perfect.’

It was late afternoon and Jeremy had come straight from the university ‘to wet the head of the house,’ as Philippa had so neatly put it. After a day spent cleaning and unpacking and discovering the secrets of her new home, Philippa had retired to the couch while Jeremy opened the champagne. Now she watched him, enjoying the warm distance that tiredness often creates, seeing his dark skin and eyes, noticing how the heavy, almost-black hair fell over his forehead, the deft gestures, the compact body whose slightness had always worried his father, and knew he could be mistaken for no one’s son but her own. He felt her gaze, looked up and smiled, and with the bottle now open and the drinks poured, came and joined her on the couch.

The summer sun was still high in the sky, yet, due to certain architectural feats in the renovation of the terrace, the room was still cool. Philippa sipped her drink and sighed. ‘I’m going to be very happy here. I love the area, the house is extremely comfortable, and it’s just the right size.’

‘Which is what the others find so disturbing. Where can the children play? Where can they take their naps? Where are we to have our family dinners?’

‘At their places.’ Philippa stood and walked to the galley kitchen at the end of the lounge. She rummaged in a box for some rice crackers, returned to her chair, took a handful and passed the dish to Jeremy. ‘Do you think I’m being unfair? Do you think I’m being selfish?’

Jeremy smiled. ‘I’m absolutely the wrong person to ask. But,’ he held up his hand to deflect her interruption, ‘you do have a life to live, your own life and not simply that of grandmother and babysitter. Selfish? The word has a bad reputation. What you’re doing is looking after yourself. I think you’re being responsible.’

‘It’s not that I don’t love them—’

‘I know.’

‘Nor is it that I don’t want to see them—’

‘Of course not.’

‘But I don’t need to see them all the time. The fact of the matter is, Jeremy, I’ve got other things to do.’

‘I know, and I’m pleased.’

‘Only vague ideas at the moment, but a host of them. This,’ she raised her arms to the room, to the little house, ‘is only the beginning.’