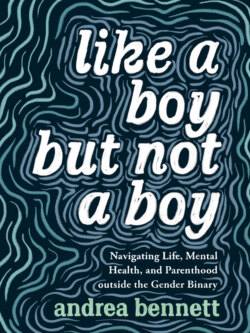

Читать книгу Like a Boy but Not a Boy - Andrea Bennett - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеjohn

JOHN WAS BORN IN 1991. They’re non-binary. They grew up on a pretty big farm, in northwestern Ontario, near Lake of the Woods, with an older brother and a younger brother. It was a very pretty part of Ontario, near the Canadian Shield—so, nice and rocky. Where John grew up, there was sometimes a grocery store. It would change hands every couple of years. There was a church, and there was a school. There were maybe 100 kids in kindergarten through grade eight in the entire school. John’s year was relatively large, and it was six people. Their older brother was one of two people in his grade. Many of the people in the area were farmers. John’s family raised beef cattle. Growing up meant mostly being stuck on the farm or in school, and occasionally seeing other people.

John’s family home was about 2,000 square feet. It had plywood floors that never ended up getting any flooring on top of them. It was a built-for-efficiency house that wasn’t very fancy. A bungalow with a crawl space for a basement. The walls were extra thick, because when John’s dad built the house he was like, “I need to have as much insulation in this house as possible.”

They went to the Canadian school that was just about a kilometre from their farm for kindergarten through grade six, and then they crossed the US border and went to a school in Baudette, Minnesota, for seventh through twelfth grade. Their mom drove them across the border every day to school.

John had to leave home to go to university. Their parents were really pro-education. There wasn’t anywhere to go in the area, apart from maybe a community college in Fort Frances an hour and a half away. John’s dad really wanted someone to take over the farm, so there was that pressure, but John knew they wouldn’t be suited to it. If John wasn’t going to take over the farm, there was nothing really for them in their hometown.

John really didn’t have much of a concept of queerness until they went to university. They knew gay people existed, but they didn’t know anyone who was out. Everything they heard about being gay growing up was pejorative, insults. They didn’t have a sense of there being any community.

John’s mom is pretty open-minded, and their dad just doesn’t care about that sort of thing, for the most part. John is not exactly out with their parents, but their mom follows their Twitter account, so she sees John tweeting about queer themes and topics, and being non-binary. It’s probably something they should have a conversation about at some point. But John is not very good at having these kinds of conversations.

As John started learning more about trans people, they remember being really fascinated but not really knowing why. They were maybe a junior in university when they learned being trans was a thing. They didn’t learn that being non-binary was a possibility until after they graduated. It wasn’t something they encountered until they came across A. Light Zachary, a writer who had they/them pronouns in their Twitter bio, and they were like, “What does that mean?” John learned more and thought, Oh, wow, that’s me.

John gave themselves permission to identify as non-binary a couple years ago, when they were living in Jersey City, New Jersey, after finishing their coursework for grad school. John was working on their thesis and had just broken up with someone. They’d been thinking a lot about gender and decided they needed to give themselves space to figure it out. After a lot of questioning, and a deep depressive period, they came to the conclusion they were non-binary. It was freeing. In part because of its inclusivity. They can say they’re non-binary, and it doesn’t erase their life before that. They were a boy for a while, and that was fine, but it wasn’t working out. For John, the term “non-binary” felt like it acknowledged a connection to their past and made space for the fact that they sometimes don’t care if people call them “he.”

John now lives in Kansas City, Missouri, which has a population of several hundred thousand people. Very sprawling. Kansas City is very liberal, for the most part, despite the fact that it is in Kansas and also Missouri. If you go to the ’burbs, it gets a little bit more conservative. John doesn’t necessarily read as queer from the outside. They paint their nails and wear rings and have long hair. Over the last year they started using “Elizabeth” as their middle name, because a friend used to call them John Elizabeth, and Elizabeth is their mom’s middle name. But they still don’t come out to that many people in day-to-day life. They have trouble advocating for themselves, so they just accept what’s given to them. People say “sir” all the time.

John feels less comfortable whenever they go anywhere outside of Kansas City. Their partner’s family is from Oklahoma, so they’ll go down to Tulsa and they’ll keep their hands in their pockets when they’re fuelling up the car in Oklahoma or southern Missouri. Or sometimes they won’t paint their nails. It depends on where they’re going.

Going back home—that’s a different beast. John is the middle kid, and their brothers will kind of tease them. Their little brother can be mean. Seeing both of their brothers together can be bad. One on one, they’re fine. But if they’re together, it can be a nightmare.

John will paint their nails when they go home, but they’ve never sat down and explained their gender to their parents. They don’t know how much their parents have deduced. Recently, too, a friend of theirs from high school has started saying that they should hang out. John isn’t sure about it. They’d want to make sure their friend was aware of their identity beforehand. And maybe the friend wouldn’t care, or maybe he would be confused. It feels weird, like this other world trying to collide with their current world.

Whenever John tweets, they think, My mom might see this, because she follows about five people. She’s kind of like a mom on Facebook, just responding to everything. John will see her in a conversation with someone like writer Joshua Whitehead and be like, “All right. She’s doing her thing. It’s okay.”