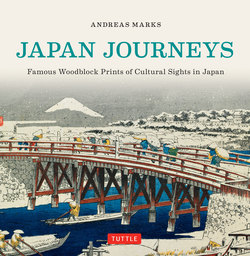

Читать книгу Japan Journeys - Andreas Marks - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Paradise for Travelers

In nineteenth-century Japan, after centuries of civil war and restrictions on individual mobility, travel became a popular leisure activity, thanks in part to the development of a network of well-built and fairly safe roads. Instead of a rough ordeal into the unknown, traveling was expected to be pleasurable and to provide opportunities to experience culinary and cultural specialties, local color, and other entertainments. This new interest in travel and enjoyment of local culture is reflected vividly in the woodblock prints of the period. Prints featuring the natural beauty and architectural riches of various regions of Japan started to gain widespread popularity by the 1830s, giving birth to a new category of print that served as an affordable memento for travelers. Thus historic views of Japan’s favorite sights have been preserved over the generations, offering a fascinating perspective on familiar cultural icons for tourists both domestic and foreign today.

TRAVEL AND PRINTS

The origin of the travel boom in Japan is found in the pilgrimages to sacred sites that became widespread among all classes during the nineteenth century. Accurate statistics of domestic tourism at this time do not exist, but it is estimated, for example, that as many as five million people participated in the 1830–1831 mass pilgrimage to Ise when the total population of Japan is believed to have been 32 million. To facilitate the growing number of travelers, lodging and dining opportunities, as well as other services, were established, especially along the main arterial roads like the Tokaido highway that connected Edo (today’s Tokyo) with Kyoto. This interest in travel and depictions thereof was further bolstered among the masses by travel stories like the bestselling serial novel by Jippensha Ikku (1766–1831), Strolling Along the Tokaido, also known as Shank’s Mare in English.

The customer seated on the left, playing the popular parlor game ken with a woman, is believed to be Hiroshige himself. Ca. 1838–40, Utagawa Hiroshige, Musashiya Restaurant in Ushijima from the series Collection of Famous Restaurants in Edo.

By shogunal decree, with very few exceptions, Japan had limited contact with foreign countries until the 1850s, when the American navy forced Japan to open its doors to the West. This opening was swiftly followed by an unparalleled modernization and Westernization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The development of railways facilitated rapid urbanization and along with that came a shift away from traditional lifestyles.

In the twenty-first century, when social networking has created a demand for a constant photographic recording of one’s life, the urge for documentation is especially apparent in the behavior of tourists, where excessive photographing and digital sharing seems to have largely replaced the once obligatory postcard writing. An obsession with capturing scenes visually has always been noticeable in Japan: in the late twentieth century, the camera-wielding Japanese tourist was a common stereotype worldwide. This interest in documenting travel is not new, and is one of the reasons why thousands of different views of Japan’s scenery were offered as commercially produced woodblock prints in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Such prints were attractive not just as a memory of a past trip but also as a visualization of a desired future journey. Today they allow us a glimpse of life at that time and provide also an image of the scenery then, although we should keep in mind that views of remote locations weren’t necessarily accurate representations but rather idealized interpretations by artists who usually did not have the opportunity to actually see these places with their own eyes. Instead, they often based their pictures on illustrations in travel guidebooks.

Two artists were especially successful in designing landscape prints and have received substantial international recognition over time: Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). Hokusai created an enormous output of several thousands of highly original prints, paintings, sketches, and book illustrations. Since around 1800, he regularly designed landscape prints and significantly influenced the genre, first and foremost with his print series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji from ca. 1829–1833.

Geisha and courtesans are seen by many as cultural icons associated with a traditional Japanese lifestyle. Ca. 1815, Kikugawa Eizan, The Courtesans Tsukioka and Hinagoto of the Hyogoya.

Ikaho is a hot spring resort in the center of Gunma Prefecture, located near the foot of Mount Haruna. 1883, Toyohara Chikanobu, Ikaho Spa, Foreigners at a Festive Meal with a Bath House in the Background.

This highly esteemed print was copied in 1887 by Vincent van Gogh in oils. 1857, Utagawa Hiroshige, Sudden Shower over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

Hiroshige’s first landscape prints appeared in the early 1830s and he subsequently became the leading landscape artist. He was especially known for several series he did depicting sights along the Tokaido road, the earliest and most famous of which is generally known as Tokaido published by Hoeido, and was issued ca. 1832–1833. The print entitled Hara: Fuji in the Morning on page 111 is an example from this series. Hiroshige was equally successful with views of famous places in Edo, such as his final series of masterworks, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, published from 1856 until 1858 of which many examples are shown in Chapter One of this book. The city of Edo was by far the most popular scenic motif in the nineteenth century and woodblock prints that feature the city include depictions of the important and popular roads, rivers, bridges, shrines, and temples, featuring them at specific times of the year, such as spring wisteria blooms at the shrine at Kameido, or summer fireworks on the Sumida River. Many of the Edo locations featured in this book are still tourist attractions today, although other areas, such as the electronic mecca of Akihabara and the nightlife district of Roppongi were established after the Second World War and are not featured in the woodblock prints of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries.

Women walk in the snow to a backdrop of one the aqueducts that supplied Edo’s water. 1853, Utagawa Hiroshige, Ochanomizu (detail) from the series Famous Places in Edo.