Читать книгу The Son - Andrej Nikolaidis - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I

ОглавлениеEverything would have been different if I’d been able to control my repulsion, I realised.

The sun was still visible through the lowered blinds. It had lost all its force and now, unable to burn, it disappeared behind the green of the olive groves which extended all the way to the pebbly beach of Valdanos and on as far as Kruče and Utjeha; bays sardined with bathers determined to absorb every last carcinogenic ray before going back to their accommodation. There they would douse their burnt skin with imitations of expensive perfumes, don their most revealing attire and dash off to discos and terraces with turbofolk music, full of confidence that tonight they would go down on another body with third-degree burns; possessing and then forgetting another human being almost identical to themselves.

At first I’d resolved to stay in bed a bit longer, but I had to get up because the stench of sweat in the room was unbearable. The room is located on the western side of the house, and it’s as hot as a foundry in there in the afternoons. The sun beats against the walls for hours and hours. Even when the bugger goes down, the walls still radiate the heat. They bombard me with it all night long. Ever since we moved into the house and I first lay in that bed, I’ve sweated. I wake at three in the morning and have to get out of bed because the pillow and the sheet are drenched with perspiration and start to stink. What’s more, they stink dreadfully – it’s simply unbearable. My own body drives me out of bed.

Making that room the bedroom was a catastrophic decision. We carried in the bed, wardrobe and bookshelves, and sealed the unhappy fate of our marriage, although we wouldn’t realise it until later. Nothing could survive the night in that room, certainly nothing as fragile and bloodless as our marriage.

For two years I sweated, woke horrified by the reek of my own body and drank coffee on the balcony for hours. Shortly before dawn, I would fall asleep again briefly on the couch in the living room. Worn out by insomnia and fatigue, I would go in and cuddle her when she woke. For two years I tried to grasp what was amiss and why everything seemed to go wrong for us. I strained my mind as best I could, exhausted by insomnia and the dissatisfaction which filled the house. For two years I wasn’t even able to think. And then it was all over. She left. ‘I can’t take this anymore’, she yelled, and was gone.

That same instant I threw myself onto the bed, where even just the night before we’d said ‘I love you’ to each other in our ritual of hypocrisy. I was asleep before I hit the pillow. I woke bathed in sweat, as usual. She really has gone – that was the first thing I thought when I opened my eyes. She wasn’t there anymore, but the bed still stank of me.

I got up and almost fled from the bed. I closed the door behind me, determined that nothing would ever leave that room again. I plodded to the kitchen and put on some water for coffee. Then I ran back to the room and locked the door twice just to be sure.

I thought it would be good to read something, I said to myself. It really was high time. For two whole years I hadn’t read anything except the crime column in the newspaper. The only things which still interested me were crime news and books about serial killers. It was as though only overt eruptions of evil could jolt me out of my indifference. I no longer had the energy for the hermeneutics of evil. That was behind me now. I could no longer stand searching for evil in the everyday actions of so-called ‘ordinary people’. Instead, I chose vulgar manifestations of evil. If a man killed thirty people and buried them under his house, that still had a wow factor for me. But I’d lost the strength to deal with the everyday animosities, suppressed desires and cheap tricks of the people I met: those who treated me as if I was blind, convinced that they’ve duped me into believing their good intentions and made a total fool of me, while I simply looked through them as if they didn’t exist.

He Offered Himself for Dinner, the paper wrote that morning. The crime column reported on the cheerful story of Armin Meiwes, a cannibal from Germany, who had joined an online cannibal community. Humans are sociable beings: they come together when they’re born, they flock together when they go off to do their military service and learn to kill other human beings, they come together to mate and to marry, and ultimately they also congregate when they want to eat one another. Meiwes had found a place where kindred souls gathered. He wanted to eat someone and confided this to his friends from the cannibal community. When he placed an announcement in the forum, replies came in from 400 people who wanted to be eaten. And so he chose one of them. It seems this fellow had particular demands: he requested that he and his benefactor celebrate a ‘last supper’ together and eat his penis before he be killed. Obliging Meiwes wanted to fulfil his wish, but after their initial enthusiasm they agreed that the meal was inedible. The paper then went on to explain how the ‘volunteer’ then felt sick and started saying the Lord’s Prayer. Meiwes, whom doctors established to be quite normal, stated that he skipped the prayer because ‘he couldn’t decide who his father was – God or the Devil – so he didn’t know whom he should be praying to’. In any case, Meiwes killed the fellow after the prayer, later ate him and filmed the whole business.

I went to the bookshelf and took down Eliot’s The Waste Land, which a friend had given us in our first summer in the house. The November of that year was rainy and condemned us to stay at home since the continuous deluges made our walks through the olive grove impossible. That month we tried to achieve the idyll from B-movies, sitting in armchairs in our living room with a fire crackling in our fireplace. We sat and read Eliot. I read aloud and she listened. I loved her then, like I always loved her. Then I couldn’t take it anymore, like I’d never been able to take it anymore. But I decided to go on after all, like I always decide I should go on. Things never fail because of me, nor do they go off well thanks to me. They always happen with me as a bystander. I just adapt to them.

As a child I imagined life as an enormous desert which I had to walk through while trying not to disturb a thing or to leave any trace. Not one footprint was to remain in the sand after I was gone, not one flake of ash from the fire I laid, not one bone of an animal I killed to eat, not one scrap of waste from the caravan I met, not one tree at the oasis whose bark I carved my initials in, not one woman in a village with a child of mine by her side. I was just passing through, and I took care that no-one noticed and was able to say: he was here. That’s how I thought back then, and that’s how I still think today. But that’s not what I did. I got married. I took a wife but continued travelling without a trace. In the end she declared ‘I can’t take this anymore!’ and left. I could have said that too, but I didn’t – she said it because she was stronger than me.

April is the cruellest month, according to Eliot. But he never lived on the Montenegrin riviera, and his fellow citizens didn’t rake in wealth by renting out rooms. He never saw tourists arriving in his peaceful town like hordes of Huns and turning it into a giant, barbarian amusement park, and he never felt how it feels when your habitat shrinks to the boundaries of your courtyard, because simply leaving the house means having to forge your way through a seething mass of foreign bodies, all of whom are ugly, loud and possessed by the pursuit of pleasure. It is this that always forces me to rush back home in panic, constantly vigilant for the omnipresent, lurking danger: I return to the world of my own property, separated by a tall fence from the rest of the world which has been occupied by unknown and terrible people. August is the cruellest month, I say.

I think it was Al-Ghazali who wrote that heaven is surrounded by suffering, whereas hell is surrounded by pleasures. Seen from up on the forested hill where my house is, the town I live in looks like hell in the summertime. Tourism is a trade in pleasure, and people in a tourist town are indeed surrounded by pleasures. So Al-Ghazali was right: I am in hell because I am surrounded by pleasures. Sartre is also right when he says hell is the others. Their pleasure is my hell.

The phone rang. A friend was calling to tell me that a DVD edition of the film Cannibal Holocaust had just arrived from America.

‘What’s that?’ I asked him.

‘A film about an expedition of film-makers, who come across a tribe of cannibals in the Amazon jungle,’ he said.

‘Sounds good for starters. What happens after that?’

‘Nothing much – the rest of the film is about the cannibals eating them. The distributors I got it from are called Grindhouse and specialise in the obscurest, most shocking and most repulsive films of all time,’ he explained, not without enthusiasm. ‘Imagine what I’ve just seen in their catalogue: there’s a whole range of films where people are put to the most terrible of tortures, raped, slashed open, quartered and eaten. There are also titles where it says No animals suffered in the making of this film. Get that?’ he yelled into the receiver.

‘I get it,’ I answered through my teeth.

‘They’re worried that some lovers of cannibalism, who watch movies of people being disembowelled, might feel squeamish about violence towards animals,’ he bellowed.

‘I’m afraid I get it,’ I said.

I realised I wouldn’t be able to read any more after that. There’s always something at the last instant which prevents me from reading. For reading and any kind of mental exertion I need leisure. If I never felt bored, I’d never write anything. And I was still bored now, as usual, but for some time I’d been unable to think why I should read or write at all and why it was important to ‘develop my mind’. I gave up all thought of reading and turned on the computer.

I couldn’t get onto the internet. The dial-up connection kept tossing me offline. The telephone exchange was overloaded due to the thousands of Kosovo-born tourists who were probably sending messages to their families in Western Europe. In the summertime, these Gastarbeiters like to show off the pittance they’ve earned by insisting on these two weeks of annual holiday which bring them only frustration: no matter how much they’ve strutted like peacocks and seduced young girls from Pec with their gold chains and ten-year-old Mercedes, the stench of the toilets they’ve cleaned and will go back to clean in Munich, Stockholm or Graz still sticks in their nostrils. Now they were back from the beach and frantically phoning and sending mails, driven by the need to communicate, despite being illiterates for whom every spoken word induced suffering like that of giving birth.

I was livid with contempt and antipathy, an abhorrence which flooded over me as completely and utterly as they say saints are suffused with love. I needed to see open space: the soothing emptiness of the sea; a blue unpolluted by people. I rushed out onto the balcony.

The first shades of night were falling. The sun was setting once more behind my great-uncle’s olive grove, which is what we called the hill laden with rows of overgrown olive trees. In fact, it was fifty hectares of viper- and boar-infested scrub blocking our view of the sea. My father claimed he had once seen ‘something otherworldly’ come down to land behind the hill. I never managed to convince him that it was just the sun. Evening after evening, we sat on the terrace waiting for darkness to fall. We watched in silence as the sun slowly disappeared behind the silhouette of the hill, which had always stood between me and the world. When the light was gone, my father would get up, state resolutely, ‘No way, that wasn’t the sun!’ and disappear into the house. From then on, the only sign of his existence would be strains of Bach which escaped from the dark of the bedroom, where he lay paralysed by the depression which had abused him for two decades.

That evening the hill caught on fire. Instead of feeling a breeze from the sea, I was hit in the face by the heat of the burning forest. The fire would erase all my father’s labours once more, I thought. After each blaze, the police scoured the terrain searching for evidence which would lead them to the culprit. Needless to say, they never found anything: not a single piece of broken glass or a match, let alone a trace of the firebug. ‘They’ll never find out who set fire to our hill, I tell you. How can they when the fire comes from another world?’ my father repeated.

When the hill burned the first time, he saw it as a sign of God: ‘My whole life had passed by without me even taking a proper look at the olive grove my uncle left me. Now there’s no olive grove left – just my obligation to the land,’ my father spoke with the fatalism so typical of this crazy, blighted family.

He built a fence around the entire hill. He worked his way through the charred forest step by step, breaking stones and driving hawthorn-wood stakes into the rock, as if into the heart of a vampire. Then he tied barbed wire to the stakes, which tore into the flesh of his hands. For months he came home black from head to toe like a coal miner who had just emerged from the deepest pit. And that’s what he was: a miner. He delved into the heart of his memories. He wasn’t clearing the charcoaled forest but digging at what was inside him, breaking the boulder which oppressed him, shovelling away the scree which had buried him alive. He came home all wet and sooty for months, until one day he announced that his work was done. The property was fenced in and cleared. He had built new dry stone walls and planted olive saplings. He took me and my mother onto the terrace and showed us my great-uncle’s olive grove for the umpteenth time. ‘I’ve resurrected it from the flames,’ my father pronounced.

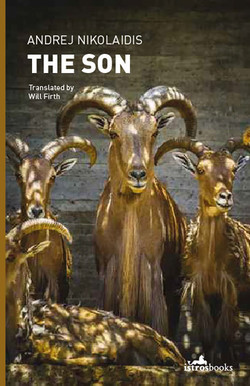

When the hill burned the second time, he installed a new fence and planted the olive trees again. As if that was not enough work, he also built a barn. Then he brought in goats from Austria. His diligence went so far that he even minded them. That year he was a goatherd. During the day he would roam over the hill with the goats; in the early evening he would bring them back to the barn for the night. ‘The pasture is excellent this year –,’ he said, ‘fresh growth is coming up from the scorched earth, and so the goats are eating the best food. Now they’re fenced in, safe from the jackals, and have a nice dry place to sleep: like a five-star hotel,’ he was fond of adding.

My mother thought she knew the root of my father’s devotion to the goats. She claimed to remember from my grandmother’s stories that my great-uncle had tuberculosis. ‘He died of it in the end, too, but he owed the last years of his life to the goats,’ my mother said. ‘A goatkeeper came from Šestani and brought him milk. He lived on even after the doctors had written him off, thanks to that milk. He had no wife or children, only your grandmother – the wife of his deceased brother, your father, and those goats up in Šestani. He lived with your grandmother and your father, and the goats helped him survive,’ my mother told me.

Born in the coastal range of Crmnica, my great-uncle had left for America in his youth. He fled his impoverished village for New York, only to go hungry in the big city for the next three years. He slept in neglected warehouses and stole vegetables from the markets to feed himself. Occasionally he would kill a stray dog, and then he thanked the Lord for the skills with knife and stick he had learnt hunting birds on Lake Skadar. ‘After the first week I knew I’d succeed. I knew I’d survive,’ he later told his brother’s wife and her son. ‘I eked out a lonely living in the middle of New York as if I was up in the wilds of Montenegro.’ The boy stared, riveted, while he spoke about the dog skin he had made shoes from. The boy had never seen his own father, but he imagined he must have looked like this uncle with the short, grizzled moustache who now came into their kitchen in shoes of strong-smelling leather (maybe even dog-leather?), hugged his mother and him, slipped some money for sweets into his pocket like uncles do, and in the evening told them tales of his adventures. What an uncle, what a man!

He made it good in America but died of a broken heart, my grandmother told my father, who later told me: ‘He never married and therefore died unhappy. “Everything I’ve done and all the roads I’ve travelled have been in vain because I’m dying without a son”, he said before he died.’ My mother, while she was alive, maintained he would have lived longer if he’d stayed in America: ‘But he came back, saw your father and fretted for the son he’d never had – that’s what killed him in the end.’

He slaved away all his life, only to die in misery. But he left all his worldly goods to his sister-in-law. That saved her from the penury she faced after her husband’s death and would have had to raise her child in. ‘All my young years I ate the fruits of my uncle’s labour; I fed on his sweat and suffering,’ my father used to say.

The man from Crmnica laboured, suffered and died. That’s the whole story about each and every one of us: the complete biography of the human race. He was buried fifty years ago, and what’s left of him is going up in flames tonight.

Now it’s all over, I thought as I watched the flames rising into the night sky. The hill was burning for the third time in ten years. The fire would be my father’s final defeat. He no longer had the strength to raise the property from the ashes again. After my mother died, the enforced loneliness he was ill-prepared for exacerbated his depression. He hardly ever left the house anymore. He would just sit in the darkened living room all day. I asked myself what he was thinking about, but in fact I didn’t really care. I just hoped he was thinking and that at least his thoughts might manage to break through the tall, smooth walls of depression which surrounded him.

That night the hill was on fire, but he didn’t go out in front of the house even to watch the flames which were swallowing up all his labours. From the balcony of my house I watched his terrace, without hope that he would appear or maybe even step through the door he had decided to die behind. His wife had died, and mine had left me. Two men, each in his own house, whom not even a fire blazing a hundred yards away could unite; not even to watch the spectacle of it devouring their property.

The burning hill sounded like the crackle of an old record. Or the hiss of a cassette. Something you could get rid of by pressing the Dolby button. But now the flames spread out of control down the slopes of the hill. I turned on the local radio and learnt that the first houses had been evacuated. Behind the first houses, of course, were more houses. And then mine. I was horrified by the thought that the whole neighbourhood had again pooled its efforts and was doing its utmost to stop the fire, and in doing so was obstructing the fire brigade in doing its job. I could just imagine the neighbours gossiping about me. ‘He’s the only one who’s not here,’ I could hear them whisper to each other. ‘It’s their property that’s burning and he’s not here. Why do we have to put out their fire?’ they asked themselves, ignoring the fact that they were out there protecting their own houses, not my olive grove. They were only fighting the fire in my olive grove because they feared it could encroach on their houses. ‘My olive grove’ wasn’t mine anyway.

They said on the radio that the government had sold all its Canadair aircraft to Croatia because it had assessed that the country didn’t need a fleet of water bombers. That was in the springtime. The coastal area had been set alight in the first days of June and was still burning – from Lastva above Tivat to Budva, Petrovac, Možura and all the way to Lake Skadar. Now Ulcinj was ablaze too: the flames had spread from my great-uncle’s hill to the first houses in the suburb of Liman. The walls of the Old Town were also at risk, the radio reported.

Since the government had sold the aeroplanes, the fire was being fought with helicopters. They were hauling up water in what looked like sacks and dropping it on the fire. The instant the water fell on the ground, smoke and steam obscured its elemental beauty. Everything vanished momentarily in grey, but the flames only needed another minute or two to re-establish their reign over my father’s property.

I soon tired of the scene. Three helicopters were now in operation, and it was plain to see that they would defeat the fire in what would be one more triumph of technology. Once technology and nature were pitted against each other in this way I felt there was nothing left for me. And yet I simply couldn’t make up my mind as to which was more monstrous: nature itself or the methods people employ in order to dominate it. Before turning and going back into the room, I glanced over to my father’s house. The lights were off, but I knew he wasn’t asleep.

It was at that point that I heard the bleating of goats. The neighbour must have been herding a flock along the road towards the house. ‘Eh, mate!’ I heard him call, and that sound made the blood freeze in my veins. I wasn’t prepared for a conversation with him. I wasn’t in the state of mind to thank him for saving my father’s goats from the fire, or to invite him in for a drink and have a good talk like good neighbours and real men are supposed to.

But he was already standing at the gate, which I always kept locked, and waving to me. Great: now there was no escape. I put on my boxers and went down to open up for him.

‘What a tragedy, eh mate?’ he droned. Fortunately he didn’t expect me to answer. As he drove the goats in through the gate he continued: ‘Everything your father did has burnt down. I only just managed to save these ones here. I got them out when the barn caught fire. There was no saving it. Such a great shame, ain’t it mate? But that’s life for you – people slave away, and sometimes you wonder what for. You slog and sweat, and then everything goes up in smoke in a flash. It was destroyed by the flames, they say. But it wasn’t the flames – it was God.’

With this kind of attitude, he was bound to be considered a wise man by those who knew him.

Finally all the goats were in the courtyard, and I realised I was already sick of the situation. The goats themselves immediately set about what they do best: surviving. These creatures, which had only just eluded death, now grazed indifferently and stank to high heaven. The billy goats were the most accomplished in that; they stank even worse than my neighbour, who doggedly came up behind me every time I tried to move away from him to get a breath of fresh air.

‘You know, old son –,’ he schmoozed, determined to get some reward for his good deed, ‘I always tell people there’s no better rakija than yours.’

‘Let’s go upstairs,’ I said, too weak to fight against the kind of incivility where people invite themselves into others’ houses.

But I hadn’t set one foot on the stairs when I was compelled to turn around abruptly, feeling as if someone was watching me. And sure enough, my paranoia was justified once again: the black he-goat was looking at me intently. His yellow eyes were staring at me in the dark. Their slit-shaped pupils looked like cracks in the earth, ready to swallow me up. He threateningly flared his nostrils, from where a gleaming trail of saliva trickled. His sharp little teeth chewed the grass I’d just walked on, and he kept his eyes on me. I was sure we were thinking about the same thing: he about how to eat me, and me about my flesh disappearing into his mouth, his teeth sinking into my body and tearing off piece after piece.

‘You all right, mate?’ I heard the man say behind me. I turned back and saw my neighbour, whom I’d completely forgotten. For the first time in my life I was glad to see him. For the first time I found comfort in another human being, despite his gap-toothed smile and half-witted gaze set beneath a low brow and red lopears. Away, away from the animals! I thought as I rushed up the stairs. My neighbour ran after me in surprise.

‘Whoa, easy does it, mate. You look a bit pale,’ I heard him say.

I led him into the house and cast one more glance at the he-goat. He was still standing in the same place and staring at me. It was as if he wanted to make it clear to me that I’d opened the gate of my house for him, that he’d entered and that he’d never leave. He’d stand there and wait for me until the end, whenever my end would be.

‘I don’t have any rakija. Do you drink whisky?’

‘I drink everything,’ he said.

I poured myself a full glass and just two fingers for him because I wanted him to leave as soon as possible. We sat in the armchairs in the living room, opposite each other. I put the bottle down on the table between us, hoping it would obstruct my view of him, but it was in vain: the table was too low and the bottle too small.

Through the balcony door, I could see the tips of the flames. They must have been frazzling what was left of the hill. Yet I found comfort in the flames. They were the perfect excuse for me not to look at the fellow in front of me. He’d think I was fretting because of the fire or that I felt sorry for my father. He tried to start a conversation but soon gave up and decided to leave me to my sorrow.

‘I’ll pour myself, mate, don’t you mind. You just go ahead and think,’ he reassured me.

After that we sat in silence. When he’d quaffed all my whisky and my neck was stiff from looking out through the balcony door, he left. As he was going, he said: ‘You’re a good man.’ I nodded, refusing to look at him. When he closed the door behind him, I burst into tears.

That’s how she cried, too, as if she was imploring someone. And that someone was me, I sometimes thought, and yet it was as if she was beseeching someone who wouldn’t hear. The only purpose of crying is self-pity, which brings us the greatest satisfaction – a wet orgasm after emotional masturbation. We pity ourselves because there’s no-one else who would. Self-pity is held in great stead. Only someone who cries and weeps convulsively over themselves can hope to gain the sympathy of others. But it only lasts an instant. Everyone turns back to themselves in a flash because people are only capable of ongoing agony in relation to themselves. And who can blame them: being alive is an unquestionably tragic fact which can induce nothing but tears.

When she finally stopped sobbing, she left me. All at once she wiped away her tears, and instead of a tearful glance she sent me one full of hate.

‘You’ve destroyed me. I curse every day of our life together,’ she snarled.

I saw clearly where this was heading. Two or three sentences more and she’d say I’d made her want to die, I thought. But she didn’t.

‘Life with you was hell,’ she said instead, ‘a hell I’m now leaving. I’m going to start life again. On second thought, I should be grateful to you because you’ve aroused the desire for life in me again: a life after you. Now I know there’s a life after death.’ She laughed hysterically. ‘Life after you. Thank you for everything,’ she shouted as she threw her things into her suitcase.

She left before I could say anything in return. I simply stood in the hall, staring at the door she’d slammed behind her, left alone in the house which until just a moment ago had been our home. What did I expect? That the door would open again, that she would come in, laugh her golden laugh and once more grace this damned house with her smile; with the smile which made me fall in love with her in the first place; the smile I married? It was only this morning that she left me, yet I can no longer remember the reason why. What happened between us? What was it that became so unbearable? I thought about her but couldn’t come up with a single reason why she found me so abhorrent, nor of how I’d become estranged from her, incapable of living close together. I knew now that I loved her. I thought about her smile and loved it like the very first day I met her, and it seemed as if nothing untoward had happened at all, nothing had changed. I realised that her leaving had brought everything full circle: she had gone and everything returned to nothing.

I remembered watching her singing in the kitchen in the immaculate light which came in through the open window, like the illumination in baroque paintings. She stood there like an angel with wings outspread, too tender for this world. It seemed only a moment before her mangled, fragile form would float heavenward and her wings would fall into the mire in which I reside. But then she started singing, and the terrible dissonance destroyed the picture.

‘Darling, you look like an angel but sing like a toad,’ I told her.

As a matter of fact, everyone becomes unbearable once we get to know them a little better. That’s why the most beautiful women are those on painters’ canvases, where they’re limited to their appearance. Beautiful they are, and that’s all we need to know about them. Because any other detail about their biographies, habits and thoughts would repulse us and turn delight into disgust. I can just imagine how the girl with the pearl earring must have stunk. Europe at that time didn’t have bathrooms, so it’s hard to think of European women of that era as anything other than carriers of the plague bacillus. This woman, as we know, was a maidservant. Before she sat for the painter determined to immortalise her beauty, in other words the lie about her, she must already have cooked the main meal, scrubbed the floors and done all the shopping. She’s sure to have worked up a sweat at least three times, and being in the same room as her must have been awful. But there’s not a man alive who doesn’t desire to kiss her when he sees her on a museum wall.

Art always lies, as a matter of fact. It seduces us with its lies like a killer seduces a girl standing in the rain in front of the school and waiting for her mother, who’s running late because her lover needed several minutes longer to reach orgasm that day. It takes us by the hand just as that girl is, blinded by lies, and leads us away from the truth, away from life. Art creates the impression that things have meaning and always happen for a reason, but the truth is different, of course: we never find out why, nor do we perceive the meaning of what happens to us. Things are neither beautiful nor justifiable. They simply stink like the sweaty body of Jesus did up on the cross, or the masses who tried to stone him and the disciples who bewailed him; they stink like the saints and sinners, the convicted and the executioners, da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, and especially van Gogh’s shoes, which Heidegger, amid the stench of beer and sausages, claimed to be those of a peasant. We, the living, stink too; we wash in vain because filth, not cleanliness, is our natural state. We clean ourselves but always get dirty again. And we stink hideously: from the day we’re born until our dying day, and even after we’re dead. We stink in both life and death.

Only now that she’s gone can she be beautiful again, and only now am I able to love her again. Because now I’m forgetting all I had learnt about her, and can allow only her beauty to remain. Her smiling face. I will cherish that image just as precious paintings are stored in high-security museums.

Apropos women…I heaved myself out of the armchair and sat again at the computer. I connected to the internet at the first attempt and typed ‘free cumshot pics’ into the search engine. It came up with 40 million porno sites, and I chose one at random. I saved several women’s faces to my desktop. Splattered with sperm, they stared up adoringly at the studs who’d just ejaculated on them as if they were pagan fertility gods. Cumshots are my favourite segment of pornography: the wanton spilling of seed, the defiant and futile squandering of fatherhood.

Ready to masturbate, I thought! After all, masturbation is the ultimate consequence of the Cartesian concept of the subject. I gazed at the image on the screen: a siliconed Korean knelt in front of a circumcised black. Talk about multicultural. Political correctness is only tolerable in pornography, I thought – this is its true place. Because what is political correctness if not a pornography of correctness?

But it wasn’t to be; this happens to me all the time. My masturbation has become excessively intellectual and too discursive for it to be possible. For months I’ve been unable to feel sexual arousal and instead resort to fulfilling a need to deconstruct porno images, can you believe it? My own hunger for the grotesque will destroy me, I yelled, pacing round and round. It was clear that my need to discover the grotesque in every detail would be the end of me: I look at everything with contempt because I see discord and misery in it all. Yet the only alternative to repulsion is compassion, which is equally lethal. In the end I’ll die, and when they’ve buried me everyone will hold me in contempt. There will be no-one to mourn for me.

‘It’s unbearable how my brain works!’ I roared.

Going out onto the balcony, I gripped the railing with both hands.

‘I can’t take this repulsion anymore,’ I cried, ‘no-one would be able to. But what can I do when I keep seeing all those things, when the wretchedness and filth drive me to disgust and pity, and when they crucify me like Christ. I’m like Christ on the cross, who instead of love for the mob who stoned him feels only disgust. And the stinker who cuffed Christ while he was carrying the cross: what if Jesus saw in him only a wretch who’d found out the day before that his wife was cheating him, and who hit him today because he didn’t slap her yesterday? What if that’s how it was? What if Christ simply loathed him? What if he laughed at those grotesque creatures and then breathed his last, adrift in the ocean of sorrow which washed over him, sorrow because of all the misery on Earth. What if that’s how it was? Everything would go down the plughole and there would be nothing but agony, like everything really has gone down the plughole and my life is nothing but agony. Death is the only fact which one can build optimism on – only death can finally bring hope…’

I stood on the balcony, howling out this tirade, and then stopped myself when I suddenly remembered my father. The terrible thought that I might waken him forced me into silence. I glanced over to his house, but he hadn’t turned on the light or come out onto the terrace. He hadn’t heard me, after all. I had avoided that reproachful question, ‘What are you doing, for goodness’ sake?’; that question which I had always found the most shameful and frustrating. Once again there was no sign of my father. I tried to recall when I’d last seen him, but I couldn’t quite remember: I now wondered if he left the house at all anymore.

If I don’t wake him, the dogs butchering each other down on the road will, I thought. A huge black tyke was tearing away at an unfortunate hunting dog. And a whole pack of dirty mutts and mongrels had come bolting up behind; canine freaks combining all the worst features of their forebears. The black tyke seized the slender hunting dog by the neck, immediately drawing blood and maddening the black leader’s entourage – that incestuous, degenerate pack. The long-bodied dog died in agony as dozens of jaws rent at it, pulled at its limbs and tore it apart on the sticky, hot asphalt. That will wake my father, I thought, and everything will end in a row, like every other conversation we’ve had since my mother died: without her standing between us as both dyke and bridge. Without her, our relationship was finally reduced to its very essence of mutual antipathy. My father had grated on my nerves even when I was a child, when I would be annoyed by everything he said or did. The trauma I carry with me from my earliest years is my father. I must have had a hundred nervous breakdowns in my childhood, and each of them because of him. Every time my father thought of giving me a goodnight kiss, of coming into my room, stroking my hair and saying something to me which he thought was affectionate – he who never learnt anything about children, who never learnt to live with his child, who never really accepted the fact that he had a child…Every time he stroked my hair and kissed me on the neck after his ‘affectionate’ and fortunately brief monologue…

He even kissed me that evening after Milan had fallen from the gnarled, enchanted, 500-year-old maple. They said it was me who had talked him into climbing it. I don’t remember that, and I don’t know why Milan climbed the tree that particular day, like I know he had many times before. Perhaps he climbed it to needlessly prove to me once again that he was the elder brother, and thus braver and stronger. It turned out that a man was hoeing around the olive trees on the property next door: he heard our argument and me telling Milan that I hated him and demanding that he climb the tree all the way to the top. Milan refused because it had rained and the bark was wet, and then the man heard me saying I would climb it instead. Soon there came a scream and the sickening sound of a bone breaking.

The body of his seven-year-old son was at the city mortuary in Bar that time my father leaned over my bed, covering me with the bridge of his body, and said, ‘Don’t cry, we love you.’ I listened to his steps receding, heard my mother’s sobs and the door of their room close. It closed once and for all for me. From that moment on, it was no longer the long hall and the two doors which separated us. Between us lay dead Milan, the blood trickling from his small, fractured skull and being borne away by the water from the old Turkish drinking fountain. From that moment on, we were separated by my guilt. My father never said that to me. He didn’t have to: it was enough for him just to look at me, or even worse, to kiss me. Every evening I awaited my punishment, but it never came. Instead there was the goodnight kiss. Only today do I realise how cruelly I was punished – that kiss was the punishment. I was ‘forgiven’, and it had been ‘decided’ that Milan’s death would never be mentioned in front of me. I was left to take care of my punishment myself. They could just as well have said: We won’t mention it but we know it was your fault, just as you know it was your fault.