Читать книгу The Long Shadows - Andrew Boone's Erlich - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

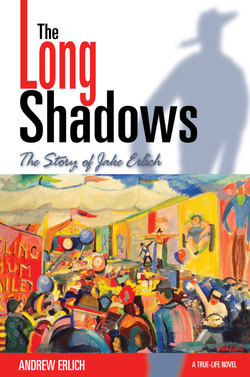

CHAPTER 5 The Neptune

ОглавлениеAfter that awful experience with the other kids down by the river, the sadness hit me really hard and escaping it became a daily struggle. It didn’t make any difference that Ben beat the hell out of Eisenbeis behind the reservoir. That melancholy was like a storm that lingered; a cold front that covered the sun for days.

I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t eat. I felt so tired. Moving was a chore. Everything took too much effort. I didn’t even want to brush my teeth. If it weren’t for Mama and Papa and not wanting to worry them I would have never left my room. I began to think that it would have been better if the Mexican who stole my shoes had just let me drown.

How would my father react if he knew the awful things I was thinking? I wondered. You’re worthless. All you do is cause your parents pain. You’ll never amount to anything. I wish you had never been born.

I snarled at myself. I imagined punching the ugly head with its protruding jaw, bulbous nose, and pimpled adolescent skin that glared back at me from the mirror above my dresser. Thinking better of it, I smashed my fist into my thigh instead. I wanted to cry but I couldn’t.

Every night I woke up sweating and unable to breathe. As alone as I felt with all of that pain, I don’t think I did a very good job of hiding it from my family. My older brother told my folks that I’d been taking back alleys to avoid people. That must have been the last straw. A few days later they came up with the idea for the trip to California.

“A change of scenery; maybe some fishing. That will be good for you,” Papa explained.

Little did Papa or I know how eventful that trip would be.

XXXX

Two weeks later, when Papa and I finally packed up the family’s Model T Ford for our trip, I just went through the motions. For all I cared, we could have been going to Fabens to pick up a crate of cantaloupe.

We departed after sundown on Saturday, driving through the night to avoid the treacherous desert heat. For two hours, quiet had filled our car like run-off from a summer rain had deluged the arroyo we passed alongside the road back in Canutillo. Somewhere just west of Las Cruces, Papa tried to break the awkward silence, but I wasn’t interested in talking. I was so cramped. Cars weren’t built for seven-and-a-half footers like me, so I had to press my knees tightly into my chest or drape my feet across the seat toward Dad.

“Did I ever tell you how we ended up in El Paso?” Papa asked.

Normally he was a man of few words and even fewer vacations. But now he was taking me on one and struggling awkwardly to make conversation. Papa’s words were forced. His behavior was out of the ordinary. It made me uncomfortable, as if his attempts to talk to me added to the heaviness I already felt in my chest. Strangely, I started to feel angry. I imagined myself pushing his words back at him so hard that they would fly past his face and out of the car window. Then they’d bounce along the highway until they finally rolled to stop by some Okie’s worn-out mattress, abandoned by the side of the road. Papa continued to speak.

“Yes, Papa,” I finally answered, looking out my window, not knowing what else to say. “But tell me again,” I said, reflexively polite.

Although I’ve always loved and respected my father, would not have hurt him for the world, and valued honesty, I was lying to him. I had about as much interest in listening to that misa (story) as I had in taking that damned trip to California. When I was younger, I loved his stories. It never bothered me that I’d heard them all before. I was just grateful to spend time with him and to connect any way I could. Although I never had any children of my own, I now realize how important it is for a father to connect with his son. It was particularly important at that time of painful transition in my life.

By the time he had finished his story, we had driven into Lordsburg and needed to stop for gas, a toilet break, and a soda pop.

Back then, the culinary options for Jews who kept kosher, like us, were limited. Sure, there were lots of choices in New York or Chicago but not where we were. There wasn’t even a deli in El Paso, let alone food for us in the badlands of New Mexico; so Mama had packed sandwiches of leftover brisket on challah, purple plums, and some of her pecan cookies.

We ate our supper without speaking, sitting on the charred stumps of two oak trees by the side of the road. Papa seemed to be wary of our surroundings. He kept glancing from the road to where our Ford was parked, as if expecting someone. I was just beginning to understand why people constantly need to be looking over their shoulders.

“I’m going to get some sleep,” I said as we pulled out of the filling station. I was determined to avoid any further conversation.

I looked away from him and out my window. My attention was drawn to the Big Dipper and then to the North Star. They were so clear in the dark desert sky. By the time we hit the Arizona state line it was past midnight. Despite the darkness, the nighttime temperature still hovered at an uncomfortable one hundred degrees.

My clothes clung to my sweaty body. I reached my right arm out the open window to try to escape the claustrophobic heat in that confining car. Even though I knew what to expect, I was surprised by the temperature of the sirocco. It scorched me. The burning wind divided around my arm, a colossal peninsula of flesh and bone; my outstretched fingers, fiords.

Just outside of Phoenix, I woke with a start as our car skidded off the road. It was lucky for us my father hadn’t been driving very fast.

“I’m sorry, Jakey. I must have dozed off,” Papa said.

A few minutes later he pulled the Model T to the side of the road to get some rest. He parked under a stand of saguaro cactus silhouetted by the light from a late-rising sickle moon. Papa immediately began to snore.

I was restless and couldn’t sleep. I looked over at him and wondered what would become of me. I still didn’t understand why we had come on that trip. Money was tight and vacations were rare. Why did he take me and not Mama and my brothers? Why had he chosen that time for our road trip? After a while, the questions and concerns that were filling my head were drowned out by a symphony of palo verde beetles, cicadas, and crickets. I drifted off into a dreamless sleep.

If it hadn’t been for a flat tire just outside of Indio where boards, not asphalt, served as the road, we would have made it to Santa Monica—or as some of my parents’ friends called it, the Coney Island of the West—by morning. Instead we arrived at noon.

I would learn that my father was a practical man. He had a clearly defined agenda for our trip. I had no idea that fishing wasn’t the primary purpose of our holiday.

As soon as we checked in to the beachfront hotel where we were to stay, Papa suggested we take a walk on Santa Monica’s bustling streets. We were supposed to be looking for a fishing store to buy gear for our excursion the next day. I was tired, but Papa insisted.

We walked up Ocean Avenue towards Wilshire Boulevard. People constantly stared at me. Papa seemed oblivious; he just ignored all the attention. I wished I could have. He stopped and spoke in English and Yiddish with passersby on almost every block. At first I just stood by in silence, clenching my jaw and gritting my teeth, wishing I’d never come on that trip. I hated all the attention. When people stared at me like they did that afternoon in Santa Monica, I wished to be invisible; that I would actually disappear. But after two hours of trudging all over Santa Monica and encountering an infinite number of gaping strangers, I’d had enough. I couldn’t take it anymore. My head throbbed with one of my all-too-frequent headaches.

We were walking away from a small grocery store. He had spent ten minutes chatting with the business’s apron-clad owner who had been sweeping the sidewalk. I stopped abruptly, spun around, and looked down at Papa.

“We’ve been walking for two hours. You’ve stopped and talked to more people than a Tammany Hall politician: Polacks, Hungarians, Galizianas, even Litvaks. Here’s a bait and tackle shop we’ve already passed three times,” I snarled, pointing to a sign above a store. “Papa, what in the Sam Hill is going on?”

He smiled sheepishly.

“Jakey, do you still mind the people?” Papa’s question took the wind out of my sails long enough for me to think about what had been happening on our walk.

“Do you mean to tell me that all this searching for fishing gear was just to get me out with the crowd?” Even though I glared down at him, my father, like little David sizing up Goliath, stood his ground.

“Just answer my question,” he said firmly.

“I can’t believe . . . !” Exasperated, I took a deep breath, inflating my cheeks like a blowfish. I sighed, hesitated, then closed my eyes and shook my head in frustration. Finally, sensing what Papa needed to hear, I tried to placate him. “Well I . . . I . . . I guess I don’t mind them. Well anyway, not as much as I did before.” I struggled to hide my sarcasm, sure I didn’t sound convincing.

Papa looked up at me and unloaded both barrels of what he’d been thinking.

“You’ve got to toughen up, kid. Just because they are looking doesn’t mean that they are laughing at you or that they know anything about you.”

Without uttering another word, Papa spun around on his heels and entered the fishing store. For about a minute I remained frozen, staring in disbelief at the empty space where he had stood an instant before. Back then my father knew just what to say to exasperate me, particularly when he said something I really needed to hear.

XXXX

That night, after a dinner of herring, corn beef, and cabbage stuffed with rice and raisins at a nearby kosher restaurant, Papa and I returned to the boardwalk. Then we stepped onto the beach, took off our shoes and socks, and rolled up our trousers. The tide was out. I ran a zigzag pattern out to where tiny waves lapped up on the beach and back to Papa. He strolled in the hard-packed sand closer to the shore. After two days of driving through the desert, the cool, salty air felt refreshing. The beach and the boardwalk were crowded. People flocked to the seashore for a moonlight swim, to enjoy the steel Ferris wheel on the pier, to indulge in frozen bananas dipped in chocolate and peanuts, to spoon on the beach, or to Charleston at one of the popular casinos.

After a while, Papa spoke to me from his heart about not wasting energy and time on what strangers think, about not giving up before even starting, about accepting what can and cannot be changed. I tried to listen, I really did, but the constant swish of the surf, the bright lights and mirrored music of the pier’s merry-go-round, the laughter, and the sounds of an orchestra escaping through a half-open ballroom window in a nearby casino grappled for my attention. Looking back on it, I didn’t want to listen to what Papa said. The distractions helped me avoid the painful realities and challenges he pushed me to face.

XXXX

Each morning I relished the chugging, almost meditative sound of the diesel engine that propelled our rickety old fishing boat through Santa Monica Bay. Before sunrise, Papa and I, along with twenty other men and a half-dozen boys, sailed from the pier on the Neptune.

On the second morning, I recall glancing back from my place by the railing on the starboard side of the bobbing boat and drinking in the orange- and purple-hued daybreak sky. I watched a black plume rising from the smoke stack disappear in the breeze. A swarm of cackling seagulls flew just below it, looking for a snack of discarded bait or fish entrails that wouldn’t be served until afternoon.

A fine salt spray covered my face. Being out in nature like that gave me a needed break from my self-consciousness. Although I still got stares from the other fishermen, my surroundings were so dramatic that they almost drowned out my need to blend in. If I noticed someone looking my way I could easily divert my attention to the ocean, the sky, my gear, or the schools of fish I imagined swarmed under the sea.

Later, as I baited my hook with a slippery sardine, Papa cast his line into the white-capped fishing bed where the Neptune was anchored. I carefully cocked my right wrist to my ear. My rented fishing rod flexed. As I whipped my arm forward, the baited line flew a third of a football field farther than my father’s had.

“You seem to be standing a bit straighter today, Jake,” Papa commented as he rewound his fishing reel.

I didn’t respond. I didn’t know if he was right or it was just wishful thinking. It would take a few more years, but I would come to recognize that changes in my posture reflected changes in my mood. I normally felt tense and withdrawn, so I tended to hunker down. Perhaps I avoided standing tall because I was frightened to get a glimpse of what more anguish might exist beyond the uncontrollable reality I’d experienced since I turned seven. Maybe I constricted myself and didn’t stand tall in some futile hope that that would stop me from growing; that I could will myself to be ordinary and end the nightmare before things got worse.

XXXX

That day, like we did each afternoon, when the Neptune docked, Papa and I gave our catch— bonita, red snapper, and albacore—to poor folks who gathered where the fishermen came ashore. As we disembarked, I carried the burlap bag that held the prizes from our day at sea. It was wet with a salty smell of ocean.

Once we were on the pier, an old gray beard with an olive complexion approached me. He walked with a limp like Kika. Then the old man snatched the bag from my hand. As he limped away, I heard him mutter “Evaristo (Thanks).” The strange sound of that word dissolved into the hustle and bustle of the Santa Monica Pier in late afternoon.

I turned around to find Papa. When I reached him I noticed that two odd characters had joined the crowd. Their apparel and the way they stared at us made them stand out. Instead of wearing sweaters and bait-stained denim and khaki like the others, these gentlemen were dressed for high tea. I think I was so aware of their clothing because I’d been envious. You see, I’d always worn hand-me-downs. The taller and thinner of the two wore a charcoal-gray suit and a black fedora on his balding head. The short and rotund one sported a coffee-colored houndstooth suit, a chocolate-brown derby, and a neatly trimmed moustache. He puffed on a half-smoked panatela.

Though I was drawn to the fine, big-city clothing they wore, something about them put me off. The two oddballs stared at me in a manner that made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. They were eyeing me with hunger and anticipation, just like the rest of the crowd was eyeing the burlap bags that the Neptune’s passengers were schlepping ashore. I would shortly learn that those two were looking for a different kind of a meal.

“Papa, the men in the suits are staring at us,” I said, elbowing my father.

“Just ignore them,” Papa replied. Before he could finish his thought the two well-dressed strangers pounced.

“Excuse me sir,” said the short one. I took a step back. “Can we please have a word with you?”

For an instant I imagined the cigar smoker looked like the Neptune would have if it were reincarnated as a man and stood upright. The tall one seemed to be measuring me with his eyes. Papa stepped in front of me, taking a protective stance.

“Why, what’s this about?” he asked in a prickly tone.

“You seem kind of touchy,” the short one said.

I saw Papa clench his fists. “What business is it of yours how I seem?! You two best back off from my boy and me or you’ll be sorry,” Papa threatened. He’s always been so protective.

“I’m so sorry if we have offended you, but we have a business proposition,” said the small one.

“Who the hell are you and what do you want?” Papa challenged with the same tone I’d seen him use with snake-oil salesmen who, from time to time, came into the store.

“My name is Zion Meyers,” said the taller of the two.

“And I’m Jerry Ash,” added the shorter one.

It turns out they were talent scouts and silent comedy film pioneers who represented Century Comedies and Universal Pictures. “We work with Carl Laemmle, the studio president. Maybe you’ve heard of him?” Ash continued.

Papa looked back at me and in a tone he normally saved for German Jews who looked down on the rest of us, he muttered: “Er es groisachti (He thinks he is a big to-do).”

“If you don’t mind, what is your name, sir?” Meyers asked.

I saw the muscles tighten in Papa’s jaw. For a moment, he stood there in silence as if to say: I do mind.

Finally he answered: “My name is Mr. Erlich, and this is my son, Jacob.”

“So you just came to Los Angeles for a fishing trip, Mr. Erlich?” Myers was making a statement with his question but I wasn’t sure what he was trying to say.

“That’s right . . . and we don’t want to be bothered. I’m not interested in buying whatever it is you’re selling.

“Please hear us out, sir,” Ash continued. ”I’m sorry if we offended you with our attention but when you come to the moving picture capital of world, how could you ever think you wouldn’t get noticed? Since you got to town, the tom-toms have been pounding.”

Papa looked at me in a silent appeal for a translation of that Jazz Age metaphor but I had no idea what it meant either.

Sensing our confusion, Ash rephrased his remark. “Since you two arrived, word has spread like wildfire about a boy giant.”

Meyers took a half step forward. “People in our line of work would kill to sign somebody up who can pull the kind of attention your boy can!”

“Nobody else has talked to you about the flickers?” Ash added.

“The flickers have not been such a big deal for us,” Papa shot back. “Please geh weg (go away). We’re not interested in you or your movie business.” Papa grabbed my arm and we started to march down the pier toward Ocean Avenue. I felt embarrassed. I towered over Papa, yet he was treating me like a child.

As I felt Papa tug me along, I wanted to stay and hear what those two had to say. Wow, the movies, I thought. Why was Papa so harsh? After all, they hadn’t done anything so bad.

I turned around to see Myers and Ash looking at each other in amazement. It turns out that Los Angeles was full of people who were constantly scouting for new and unique talent to help their movies stand out from all the rest that rolled out of Hollywood. The town was full of actors who would have given their eyeteeth for such an opportunity.

Like cheetahs who’ve gotten a scent of prey, they ran after us. I heard their footsteps just behind us. Papa and I stopped. He turned around to face our pursuers, his face red.

“Please, Mr. Erlich . . . hear what we have to say. It’s a great opportunity for this bocher (young boy) and your family. All we ask is fifteen minutes,” Ash pleaded.

That was a one-in-a-million chance. At that instant I didn’t stop to think about the downside, about how scary it would be to leave my family in El Paso, to move to Los Angeles alone and to work in pictures. Somewhere deep inside I didn’t feel frightened. I just felt desperate. I understand that sometimes fate uses desperation to make itself heard. For the first time in my short life I had the opportunity to reach for the brass ring. When would somebody like me ever get a chance like that again? No matter what Papa thought, I couldn’t let it pass me by.

“I think we should listen to what they have to say,” I said.

Papa turned to look at me. We were both surprised at my audacity. You see, in those days, neither of us was accustomed to me speaking up like that. Asserting myself would be a lifelong challenge.

Papa must have seen the determination in my eyes. He looked away and grumbled a word or two in Yiddish and stared out over the railing on the pier to the ocean. He looked as if he were waiting for something or someone, perhaps a tramp steamer from Shanghai that carried a mysterious passenger who would tell him how to resolve his ambivalence about what to do next.

“Okay, okay, but just fifteen minutes is all.” Papa finally agreed.

To this day I don’t know why Papa changed his mind. Maybe it was his destiny, too. I felt relieved. Ash and Meyers looked like they just received a stay of execution from a firing squad. Papa looked like he was still ready to pull the trigger.

The four of us ducked into The Crab Catcher, a seedy restaurant at the end of the pier. The first thing I noticed when we entered that place was the smell of stale beer and the two drunken sailors at the bar, their heads pillowed on their arms.

An apron-clad waitress with curly blonde hair and very red lips led us across the sawdust-covered floor to a small table in the back. From the moment we sat down with the well-dressed cheetahs I sensed Papa’s impatience. Three of us ordered cherry pie and coffee; Papa just waived his hand curtly: “Nothing for me.”

For about five minutes no one said a thing. After Papa’s initial outburst, Ash and Meyers seemed to be cautious, politely avoiding any semblance of a hard sell. They just sat there and looked at us as they ate their pie.

I looked up at the thick, black fishing net and white buoys that hung from the roof of the darkened restaurant serving as ersatz maritime décor. When Papa took out his Hamilton pocket watch to check the time, I saw myself as a huge swordfish, frantically thrashing about in that net.

What Meyers and Ash didn’t know was that when Papa said we only had fifteen minutes, he meant business. Now there were only ten minutes to go. Soon Papa would say time was up. Hurry up you schmendriks, I thought. Finally, Ash put down his fork and wiped his lips with the napkin.

“Mr. Erlich, we would like to offer your son a contract to try him out working as an actor in pictures at Century Comedies. We can make him a star. Someone like your boy would be perfect for—”

“Huh?!” my exhale was punctuated by a question mark and shock. The whole thing felt unreal, like a dream.

“Whoa, whoa!” Papa almost yelled, as if he were still in the Russian Cavalry. For a moment I imagined him atop a runaway horse that had his ear shot off, sawing at the reins, and trying to stop his stampeding mount.

I felt sick. I felt I was about to cry. I put my hand over my face. He’s going to ruin it. He’s going to ruin it. I don’t know what it is yet, but he’s going to ruin it, I thought. Patience was a virtue I had yet to learn. Suddenly, I confronted the loss of a destiny I hadn’t even known I had just a half hour before.

“My son’s not an actor, much less a professional actor,” Papa argued.

I stopped myself from slamming my hands down on the table. I felt wild. “Papa don’t you remember, I’ve had a year of drama at El Paso High?” I pleaded.

“Don’t worry about that,” said Meyers. “We can teach him to act. He’ll make a good living. Anyway it’s only for one picture. If you or Jake is unhappy after we finish shooting, then you can stop. But if he likes it—and you like it—this could be the beginning of something big.”

“What do you have to lose?” asked Ash.

“Yeah, Papa, what do we have to lose?” I added for emphasis.

Papa held up his hands. My father could be stubborn, especially if he felt forced into something. But I couldn’t hold myself back. I experienced a unique feeling I’d never had; certainty about what I wanted to do. That kind of certainty would be in short supply when it came to making my decision about staying or leaving the circus.

After a minute, Papa looked at me and then at the two men. He looked down at his folded hands on the gingham tablecloth. Then, as though it weighed fifty pounds, he slowly lifted his head.

“This is a ganza (big) decision. I need to think about it and talk to the Missus. I will contact you within the week.” Papa abruptly stood up and extended his hand.

Myers and Ash looked uncomfortable. After all, they were so close to closing the deal. I bet it was unnatural for them, but they must have sensed the need to go slow with someone like Papa.

At that moment I was elated, flying, but I bit my lower lip almost until it bled. That forced me to come back down to the real world. I reminded myself that Mama would be more difficult to convince than Papa.

On the taxi ride back to our hotel I couldn’t believe what was happening to me. I was so anxious my head spun. I could barely think, let alone listen to Papa speak.

“I don’t know, Jakey. The movies . . . such a big city . . . what about school? We’ll have to call Mama.”

I took a deep breath as he spoke. I whiffed the scent of something sweet yet distant, like the aroma of the first tiny honeysuckle blossom in the desert in late winter. You can’t see it, yet you’re sure it’s there. You might say that for the first time since I was seven, I smelled hope.

XXXX

That night, sleep was definitely out of the question. But that sleeplessness was different than what I had experienced earlier in the summer. I wasn’t haunted by memories of what Epstein and the other doctors had foretold for my future or by the traumatic memories of cruel taunts and teasing. I was thrilled but also frightened.

Earlier that night, Papa had challenged me. He recalled how I had spent the summer hiding in my room and how, in my effort to avoid people, I had even skipped out on my job as a lifeguard at the reservoir. Later, tossing and turning in the cramped hotel bed, I played and replayed Papa’s words. They were like a song in my head, the kind you can’t forget.

“How will you ever handle all the attention?” he’d said to me.

Papa was right; I loathed attention. Yet, the December before, when I wore the raggedy Santa suit in front of my parents’ store, I remember how I felt absolutely carbonated. That mangy costume felt comfortable. When I did my Saint Nick impression, the ragtag group of children and not a few adults swarmed me on the sidewalk. The commotion brought out Morris Thurmond, the photographer whose studio was across the street. When he set up to take my picture, about a hundred shoppers—Mexicans, Texans, and a few Tigua Indians—all rushed to be in that shot. The three hours I spent in costume went by like three minutes. I felt free in a way I’d never felt before. I never told Papa or Mama, but I couldn’t wait for next Christmas. That’s kind of strange for a Jewish boy.

I wondered if playing roles in Hollywood would make me feel like that. I started to drift off. If Mama blessed this whole business, which was very unlikely, I couldn’t imagine what life in the movies would really be like; just like later when I couldn’t imagine what life would be like without the circus. How would I learn to act in front of a camera? Would my bosses be kind? I had only been away from my mother and father once. That was just a weekend trip with the Kahn’s when I was eight and went with them and Abbie to their cabin in Cloudcroft. Since there was no way I’d fit in their bunk beds, I had to sleep on the floor. Those two days I was up there with them in the mountains, I cried myself to sleep. How could I ever live on my own without my family?

The last thing I remember that night in our hotel in Santa Monica was a gray image: me under bright lights in a brown cowboy outfit, complete with boots, sheep skin chaps, silver-engraved six-guns, a tin star, and a ten-gallon hat. Just before I fell asleep, I thought I heard the crisp, booming sound of a movie director’s voice: “Roll ‘em.”

XXXX

At about seven o’clock the next morning, we called Mama from the pay phone in the hotel lobby. I bounded down the three flights of stairs well ahead of Papa, carrying Treasure Island in my right hand. I was so anxious for him to make the call; I figured reading would help me pass the time. Books have always helped me to calm down. But that morning I couldn’t concentrate enough to read even one sentence. I waited impatiently for Papa by the stairs.

It seemed like it took him two weeks to reach the lobby. When he finally did, we walked past the registration desk and Mrs. Tomasic, the hotel owner’s mother. She seemed to perennially stand guard from her post; her small, ancient frame almost hidden by the overstuffed green and orange floral couch where she always sat in the middle of the room.

Mrs. Tomasic put down her Daily Forward. How could I ever have imagined that newspaper would write articles about me in the future? She looked us up and down as if we were thieves in the night, and grunted, “Guten Tag.” Without so much as a smile, she lifted her paper and began reading again.

At that early hour, besides the desk clerk and a skinny bellhop whose pants were too short, Mrs. Tomasic was the only person in sight. I was relieved. I didn’t want a pack of strangers eavesdropping on my parents’ discussion about my future.

Papa approached the public telephone that was mounted on the middle of a beige wall at the rear of the lobby next to a magazine rack. He lifted the large black receiver and rapidly depressed the metal lever that had supported it two times.

“Operator, operator,” he demanded. An instant later I heard Papa say, “I want to make a station-to-station collect call to El Paso, Texas. The number is 4256.”

Papa replaced the receiver and looked over at me where I was standing about four feet behind him. I took a step closer. Mama would have just opened Geneva for business. I imagined her standing in front of the open safe, counting out the U.S. currency and Mexican pesos she would use to make change for customers. At that hour, Ben would be washing the windows and Myer would be dusting the glass showcases in the store.

The phone rang. “Yes, yes my name is Erlich, Isadore Erlich,” Papa said. “Hello Mamala, it’s Yitzhak. No, nothing is wrong! We are having a wonderful time. But I have something very important to tell you . . . No! I promise nothing is wrong . . . Jakey is right here . . . Yes, he’s fine.”

I inched closer and struggled to make out what they were saying, but not so close as to make my father feel I was intruding. I held the book in front my nose, but even Long John Silver couldn’t hold my attention. Papa lowered his voice to prevent me from hearing. I knew he was telling Mama about the meeting with Meyers and Ash and their offer.

I imagined that Mama’s scream of disapproval was so deafening it pierced the distance and traveled across three states from Texas to the Pacific Coast without the need of Mr. Graham Bell’s invention: “No . . . No way . . . never . . . not over my dead body will I let my little boy move to such a God-forsaken place with strangers—actors no less! Hollywood. Puey.” I could just see her spitting as she enunciated the word. “He’s just a child. How do you know these two talent scouts aren’t ganuveem (thieves)?”

Papa’s voice brought me back to the real world.

“I know I know, but he’s been so sad. When he finishes school if something should happen to us, how will he make a living in El Paso?” Papa asked.

In order to keep my fearful fantasy about Mama’s response at bay, I anxiously tried to weave together the entire conversation from the few fragments I heard.

“Yes, of course . . . but maybe the movies would be a place where his height would help him.”

I found myself pacing back and forth.

“Ya, ya, I’m worried about it as well. Who would watch him? Show people?”

“Papa!” I roared. He was about to murder my movie career. The sound of my own voice startled me. It woke up the bellhop, who had fallen asleep where he was standing. It got the clerk to raise his head from the numbers he was inscribing in the ledger. It so unnerved Mrs. Tomasic that she looked up from her newspaper and angrily opened it to the next page. But Papa just ignored me and went on talking. I wanted to grab the phone from Papa’s hand and beg Mama to let me accept the offer and move to Hollywood.

“Certainly, but he’ll never be happy working in the store. It’s not for him,” he continued. Papa was right. “I hate to say it, but . . . ” His voice trailed off so I couldn’t hear the rest of what Papa said.

Then there was an uncomfortable, and what felt like unending, silence. Papa listened for several minutes, nodding his head in agreement as the words that would determine my fate were magically transported across space. I watched Papa, but visualized Mama slicing and carving the idea of me moving to California and finally, in a fatal coup-de-grâce, stabbing it in the heart. I looked down at the hotel lobby’s warped wooden floor and mourned for the loss of my future.

“We’ll take the first train tomorrow morning. Don’t worry about the car. The Gattagnos are out here on vacation. I’m sure they wouldn’t mind driving the Ford back and saving the train fare . . . Ya, I love you, too!” Then he hung up.

Slowly, Papa turned to gaze up at me, understanding my need for an immediate answer. He looked mischievous. “I’m not sure, Jakey. We’ll see what Mama says when we get home,” he said with a sly smile and a wink.

It wasn’t like my father to wink. He wasn’t a winking sort of a man.

“Papa!”

Reborn with hope and possibility, my mind danced. I started to ask him a question.

“Sha!” Papa held up his right hand to stop my onslaught. “Not another word until we get home.”

I bit my tongue and galloped to the stairs, taking them two at a time. When I reached our room, I was so wound up that I ran into the closed door and dropped my book. Questions that my excitement had kept at bay began to come to me, first in a trickle, than in a flood.

If I move to Hollywood, where will I eat? Where will I sleep? Inside the room, I spun around and around trying to remember where I stashed my suitcase. I noticed that my spinning quieted my questions, though just for an instant. The questions resurfaced, louder and more intrusive. Will they stare at me? Who will look after me? What if I get sick? What if I make a mistake? Will they yell at me? Will they laugh?

I spun faster and faster, whirling like some kind of a dervish, intoxicated on the divine. I crashed into the bedside table and sent the lamp flying. Moving so fast, fueled on excitement and the need to flee my reservations, I couldn’t stop or calm myself. I collapsed on the bed, breathless and uncertain about the promise of a future I never dreamed possible.

Even if I could have spun as fast as a Sufi and answered the torrent of all those questions with the wisdom of a gaon (a Talmudic Scholar considered a genius), I could not have foretold the hard knocks and danger that lay ahead, the least of which was Papa’s anger at me because of the lamp I had just destroyed.