Читать книгу Reframing Randolph - Andrew E. Kersten - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

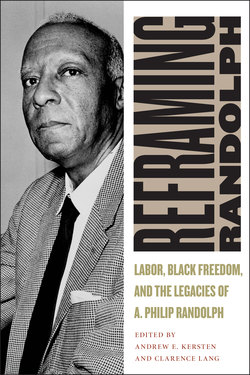

A. Philip Randolph

Emerging Socialist Radical

ERIC ARNESEN

Settling permanently in New York in 1911, Asa Philip Randolph was but one among tens of thousands of African Americans who sought opportunity, freedom, and adventure beyond the stifling confines of the segregated South in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With a religious background, modest but solid education, and notable lack of material resources of any kind, he initially exhibited few distinguishing characteristics that would set him apart from other migrants of the pre–World War I era. Yet in a remarkably brief time, Randolph had earned a reputation as one of the leading “Negro Marxians” whose radicalism eclipsed that of even the dominant civil rights proponent W. E. B. Du Bois. The magazine he cofounded and coedited, the Messenger, became, in the view of fellow Jacksonville-native-turned-New Yorker James Weldon Johnson, “the most widely circulated of all the radical periodicals and probably the most influential.” According to the anti-radical Lusk Committee of the New York State legislature, the journal was published by “one of the most active groups of Negro radicals” who were devoted to promoting the “principles of internationalism and the stimulation of the class struggle.” The Messenger, concluded Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, was “by long odds the most able and the most dangerous of all the Negro publications.”1 In the eyes of their contemporary opponents, according to the black social scientist Abram L. Harris, Randolph (and his collaborator, Chandler Owen) had become “wild-eyed ‘Reds’ of the deepest dye.”2 The man who “has been hailed at times as the greatest leader of his race since Frederick Douglass,” as one journalist put it in 1959, began his political career squarely on the socialist Left.3

How had Randolph transformed himself from a son of an American Methodist Episcopal (AME) minister in Florida to a socialist and “New Crowd Negro” during and after World War I? That Randolph threw himself into the radical milieu of Progressive Era New York and emerged as a militant socialist and civil rights advocate during World War I is well documented and understood. The origins and evolution of his radicalism are less clear. Tracing those origins is no simple task. In a 1944 portrait, Rosenwald Fund president Edwin R. Embree captured the difficulties in reconstructing Randolph’s early political journey. “About these early days—the life in Florida and the struggles in New York—Randolph does not talk much,” he explained. “It is clear that his interests are not in friends or family, but in ‘the cause.’ And there is no record that gives more than a vague picture of his life up to the time of the First World War and the beginning of his long fight for labor and the common man. From then on the record is full and heroic. And about these ‘serious things’ Randolph is ready enough to talk.”4 Because Randolph himself is virtually the only source on his early life and the development of his political vision, his recollections must be scrutinized carefully. But when they are combined with a more solid evidentiary trail from 1916 onward, it is possible to chart Randolph’s political trajectory. The radicalism he eventually adopted was an idiosyncratic one, drawing upon elements of both socialist and African American protest traditions. A lyrical and sometimes acerbic writer, Randolph was never a particularly original thinker. Rather, the power of his arguments lay in the strong moralism he brought to his analyses of American society, his ability to synthesize and apply socialist doctrine to the plight of African Americans, his uncompromising critique of existing black leadership and advocacy of aggressive New Negro radicalism, and his ever-optimistic belief that, however dire the situation, fundamental progressive change was indeed possible. The positions he advanced put him at odds not only with the U.S. government and American economic institutions but also with black conservatives, civil rights militants, black nationalists, and the small but vocal Communist movement as well. Despite hostility from the Right and Left, Randolph staked out provocative political positions and maintained his intellectual independence throughout the tumultuous era of the Great War and its aftermath.

Asa (as he was called as a boy) was born in Florida in 1889, the child of a self-educated, poor itinerant minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, James W. Randolph, and his wife, Elizabeth Robinson Randolph.5 The Randolph household inculcated two enduring traits in Asa. The first was a passionate commitment to education, which Asa and his older brother, James, acquired from multiple sources. Outside of formal schooling, they attended Sunday school and evening church class meetings and received tutoring from neighbors. (“By the time we got to school,” Randolph remarked in 1966, “we had the equivalent of a primary school education.”) Their out-of-school education covered the spectrum from religion and history to politics and current events. Whatever the subject, the subtext of race was never far from the surface. “Reading the Bible aloud was as much a part of the routine of our home as suppertime,” Asa recounted. But the biblical history Asa and James were steeped in challenged racially traditional accounts. “Jesus Christ was not white,” the Reverend Randolph would tell his sons. “Angels have no color. God has none.” He repeatedly emphasized the simple “historic fact that Jesus Christ, God, Moses, Peter, Paul and the great characters of the Bible weren’t white as pictured, but were colored or swarthy.” Reflecting back upon his father’s stories, Asa never knew if his father was aware of what he called the “economic, political, social and psychological motivation and machinery” behind the depiction of biblical figures as white. But the impact was profound: His father’s stories provided a “deep sense of solace and belonging and inner faith in the future.”6

From their parents and their instructors, the Randolph boys absorbed an abiding passion for reading, learning, and intellectual engagement that distinguished them throughout their teenage years. Both made extensive use of a small segregated library in town and pestered their father to buy them books from old bookstores.7 The “dominant climate of the home was ideas,” Asa recounted. With books by Herbert Spencer and Thomas Paine under their belt, James and Asa would engage in “intellectual gymnastics” and “intellectual entertainment” by debating at length the existence of God. These “intellectualities,” as Asa called them, could engage the Randolph boys “for hours, sometimes daily.”8 Their training at the private, religious Cookman Institute, where they excelled, immersed them in a classical education.

The second trait inculcated in Asa was an interest in politics and political commitment. Race again was central. “I spent a lot of my time accompanying my father to his churches in various parts of Florida,” Randolph remarked. As he got to know his fathers’ parishioners, Asa “listened to the stories . . . about work, racial prejudice and things of that sort.”9 From the time he was five or six through his teenage years, Asa and his brother would listen closely to the presiding bishops and church elders preach and review the year’s accomplishments. The Reverend Randolph took pride in introducing his sons to the visiting dignitaries. The highlight for the youngest Randolph—“one of the most exciting and hair-raising incidents” he had ever witnessed—took place during a speech by the legendary Bishop Henry McNeal Turner. According to Randolph’s recollection, the “ex-slave, first colored chaplain to the U.S. Army, and former member of the Georgia Legislature, pulled a 38-caliber revolver out of his pocket and laid it on the Bible and exclaimed with a sense of burning passion and anger that he had to carry this weapon in some of the jungles of the South in order to be able to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ.” The shocked congregation burst into enthusiastic endorsement at this “exhibition of matchless courage.” As a “fire-eating black prophet of Negro racial salvation,” Turner was one of Randolph’s boyhood heroes. Having been introduced to Turner by his father and having shaken his hand was, as Asa later put it, an “unforgettable trans-figuratively creative experience,” an inspiration “which caused me to feel I could storm the heavens in search of freedom and justice for black Americans.”10 With the memory of black Republican leadership during Reconstruction “very much alive in his mind,” Reverend Randolph “talked forever of the great days when Negro Republicans had served in the Congress and the Senate.” The broader pantheon of black heroes included AME Church founders Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, the early nineteenth-century black businessman and abolitionist James Forten, the Haitian slave rebel and revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman, and the abolitionists Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass.11

The Reverend James and Elizabeth Randolph expected significant things from their sons. Their emphasis on education, achievement, morality, and community instilled not just a sense of racial pride but self-confidence as well. The Randolph boys were “constantly and continuously” being told that “You are as able, you are as competent, you have as much intellectuality as any individual, any white boy of your age and even older than you are, and you are not supposed to bow and take a back seat for anybody.” Those lectures had their intended effect, for Asa and James “never felt that we were inferior to any white boy, never had that concept at all.”12 But the parental cultivation of pride and confidence were not ends in themselves, for the Reverend Randolph sought to direct his sons—his younger one in particular—toward the ministry where they could use their talents to spread the Lord’s word and, perhaps equally important, to do things that “will help other people as well as yourself.” Randolph recalled his father praising his sons’ verbal abilities and academic skills and his reminding them of how much faith their teachers had placed in them. They “believe you’re unusually gifted chaps,” he informed James and Asa, and “you’ve got to make use of that.” The goal, he stressed, was to “create conditions that will help the people farther down who don’t have your opportunities or don’t have your gifts.”13

Asa did not join the ministry, but he did absorb his father’s larger life lesson about leadership in the service of the race. Whether he did so at the time remains unclear. At the age of eighty-three, he seemed to locate the specific origins of his political activism in his high school years. His youthful daydreams, he explained, involved “carrying on some program for the abolition of racial discrimination.” Personal monetary success was not part of his agenda. What concerned him, by his own account, was a sense of obligation that the young African American had to “make a place in the world that would benefit more people than himself” and “to engage in various pursuits that would not only help Negroes but help the country and help abolish racial discrimination.”14 Perhaps he was guided by W. E. B. Du Bois’s pointed critique of the racial accommodationism of the then-most powerful black leader, Booker T. Washington. One journalist explained in 1969 that a fourteen-year-old Randolph “found direction for his life” when he first encountered Du Bois’s 1903 The Souls of Black Folk. “Negroes of superior intellect, said Du Bois, should help their fellow Negroes rise as high as they are equipped to,” explained the reporter. That book planted the idea of the “Talented Tenth” in his mind. And “Randolph decided he would be one of the 10th.”15

This was no small ambition for a poor high school student coming of age at a time that scholar Rayford Logan later identified as the “nadir” for black Americans. Perhaps Randolph and later journalists faithfully rendered his intellectual and political trajectory; perhaps an elderly man was reading back onto his early youth the passions of his young adulthood. Whatever the case, nothing in particular stood out in his academic or extracurricular life to confirm definitively his account. Growing up in the stifling and dangerous Jim Crow South, the young Randolph pursued his studies, enthusiastically played baseball, and excelled at singing. While imagining for himself a life in the theater, he patiently learned his Latin, practiced his elocution in school and in church, became an avid reader, and emerged a skilled debater. “Our home was marked and distinguished for prayers, poverty and pride,” he later observed in an unpublished autobiographical reflection, and from his parents he acquired self-confidence, racial self-respect, a disinterest in material goods, a stern sense of morality, and a commitment to serve the race.16 All of these traits would serve him exceptionally well when he explicitly chose a life of progressive and civil rights activism. Even if he had not actually envisioned a life of political engagement in his youth, his Jacksonville upbringing constituted fertile soil in which the seeds his father planted might later grow. But if Du Bois succeeded in opening Randolph’s eyes in 1903 and pushing him toward a more radical outlook, it would take less than a decade and a half for the student to reject the teacher’s insights as wholly inadequate to the task of the liberation of the race. Although conceding that Du Bois possessed “more intelligence than most Negro editors,” Randolph and his intellectual and editorial partner, Chandler Owen, denounced the NAACP leader as “comparatively ignorant of the world problems of sociological and economic significance.”17 Du Bois might be “the most distinguished Negro in the United States,” but his advice was “puerile and effete . . . not worthy of an alleged Negro sociologist.”18 If Randolph had drawn inspiration from Du Bois, he was later quick to put considerable distance between his own radicalism and that of Du Bois.

Whatever his thinking as a teenager, Asa’s geographical horizons had to expand before his political horizons could. The road to an activist politics first carried Randolph to New York, where he immersed himself in new intellectual and radical communities profoundly different from those in his native Jacksonville. This brings us to the second part of this biographical introduction: a political coming-of-age story that began when Asa joined the migrant stream that was steadily carrying the South’s Talented Tenth to a region that would soon be called a “land of hope.” The twenty-two-year-old Asa arrived in New York City in 1911, at the end of a small but steady movement of southern blacks to the North that had tripled the city’s black population between 1890 and 1910. In some ways, the city to which he moved depressingly resembled the world he left behind. Just over a decade before his arrival, one journalist had concluded that the “prospect for the Negro in New York City is not very encouraging,” for not only had an anti-black riot in 1900 revealed police indifference to blacks’ safety but the “opportunities of Negroes are less in New York than they have ever been, and there does not seem any likelihood that present conditions will be immediately changed.”19 Any black man or woman attempting to secure employment would have run up against employment barriers that relegated them to menial, unskilled work. The year after Randolph’s arrival, sociologist George Edmund Haynes found that “the large majority of Negroes are employed today in occupations of domestic and personal service” in New York, and that their relegation to such jobs was the result of “the historical conditions of servitude, of a prejudice on the part of white workmen and employers,” and the “inefficiency of Negro-wage-earners.”20 The job market hardly beckoned; opportunities remained restricted.

For a number of years, Asa Randolph joined thousands of other black New Yorkers, old timers and new arrivals alike, in maneuvering the low-wage common labor market and living what one observer called the “hand-to-mouth existence so common to Negro migrants of that period.”21 He kept few jobs for long. At one point he was a hall-boy in apartment buildings on 89th Street where a cousin worked as a janitor; his effort to become a waiter on a Fall River Line steamship ended quickly when he was fired either for attempting to unionize his fellow waiters over poor conditions or for screwing up a white customer’s order for little neck clams, or for both. (His accounts of that incident vary.) Then, he commuted from New York to Jersey City to work as a counter waiter boy in a restaurant.22 During these years before the U.S. entry into World War I, Randolph barely eked out a living on his own wages.

If his work experiences resembled those available to blacks in the South, in other ways Randolph’s New York was a world away from the Jacksonville of his youth. The rapid relocation of Manhattan’s black population north to Harlem was in the process of transforming that community into what would soon be viewed as the “Negro Mecca,” the vibrant, cultural capital of black America. Although “Harlem wasn’t the Harlem it is now,” an elderly old Randolph reminisced, its “Negro artistic and literary life . . . was developing rapidly.” Harlem, already home to a “type of Negro artist, musicians, singers and so forth, that were on a high order from the point of view of quality,” appealed to the young Randolph’s vocational aspiration: to become an actor. As a newcomer to the nation’s largest city, he soon found fellowship and an institutional anchor in the Salem Methodist Church’s Epworth League, a youth group sponsored by the Methodist Episcopal Church.23 It was through an Epworth connection that Asa met Lucille Greene; among their common interests were political radicalism and Shakespeare. They married in 1914.

Dissuaded by his parents’ objections to his potential acting career, Randolph channeled his energies into another avenue: socialism. Working odd jobs during the day, Randolph explored New York City and discovered a world of learning—and radicalism. In 1912, he enrolled in inexpensive night classes at City College—then among “the hottest beds of radicalism in New York City,” as he put it.24 Randolph studied public speaking, political science, history, philosophy, and economics. It was in this interracial intellectual milieu that he first encountered the arguments of socialist thinkers and studied the history of workers’ movements in Europe. According to biographer Jervis Anderson, Randolph was so excited by his discovery of the Left that “in his spare time, he ‘began reading Marx as children read Alice in Wonderland.’”25 As an Ebony magazine portrait recounted in 1958, this young man, “always hungry for learning,” found an intellectual home in New York. “In libraries and rented rooms he feasted on books of all kinds.”26

Study led to action. In the realm of practice, he helped to found an Independent Political Council as a forum for the discussion of political issues and the advancement of a radical critique. “We were having a great time,” Randolph told Anderson. “We didn’t think of the future, of establishing a home, getting ahead, or things of that sort. Those things weren’t as important as creating unrest among Negroes.”27 Meeting Chandler Owen at a party at Madame C. J. Walker’s home in 1915, Randolph found an intellectual soul mate. They challenged one another intellectually, undertaking an independent course of study of Marxian socialism and Lester Ward’s sociology, spending countless hours reading and discussing at the New York Public Library or at the Randolphs’ apartment, attending radical meetings addressed by such left-wing luminaries as Eugene V. Debs, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, or Morris Hillquit, and soaking in the soapbox oratory of Hubert Harrison. In 1916, they opposed military preparedness efforts in Harlem and campaigned for the Socialists’ presidential candidate, Allan Benson, while maintaining their political independence. “We are not Socialists. We are not anything,” Randolph made clear.28 That independence was short-lived; the two young black men joined the Socialist Party (SP) in 1917. Later that year, they founded the self-consciously radical Messenger magazine, with financial assistance from the Socialists, and threw themselves into the mayoral campaign of socialist candidate Morris Hillquit, coordinating the party’s efforts in Harlem.29

At a time of tremendous ferment marked by the emergence of so many ideological currents analyzing the ills of American life and proposing solutions for transcending them, Randolph without reservation cast his lot with the Socialist Party. For a young black migrant making New York his home in the prewar years, a turn toward socialism was hardly a logical or popular choice. It was, rather, a move that put Randolph at odds not only with most of the African American establishment but with many black critics of the social order as well. Within the broader black community, mainstream civil rights leaders dismissed the party as too utopian to be of value to the black cause, while the rising leader Marcus Garvey and his nationalist Universal Negro Improvement Association dismissed it as simply another tool of the white race; other black radicals simply found the party too class-focused and insufficiently race-focused to warrant their support. Unmoved by criticisms from either his right or left, Randolph maintained his faith in the Socialist Party against considerable odds, sticking with it through thick and thin. That decision took him down a somewhat lonely and certainly unpopular political road.

By the time Randolph had joined the Socialist Party, the organization had already passed its “high-water mark,” in Daniel Bell’s words.30 The party’s ability to attract votes peaked in 1912, with its perennial presidential candidate, Eugene V. Debs, garnering some 6 percent of the national total. With the outbreak of the World War I in Europe in 1914, the myth of working-class internationalism was shattered as Europe’s socialists put aside cross-border class solidarity and took up arms for their respective countries. By the following year, party membership in the United States had fallen to just eighty thousand (down from 125,000 in 1912); when its numbers began rising again, it was new European immigrants, not native-born whites or African Americans, who made up the reconstituted party. And when the United States finally entered the war in April 1917, the debate over the SP’s stance nearly tore the organization apart. In the end, many of its prewar leaders broke with the party over its antiwar stance and instead allied themselves with President Woodrow Wilson. What internal dissension failed to accomplish, governmental and extralegal repression did. By the war’s end, government persecutions, along with numerous arrests and convictions, decimated the party.31

Ideological fissures and government hostility notwithstanding, the Socialist Party’s appeal to African Americans was virtually nonexistent. That black ministers, journalists, and businessmen would object to the party and its anti-capitalist goals is not surprising, for their abiding hostility to white organized labor—whose execrable track record on race made it an enduring target of black contempt—and embrace of captains of industry as offering black workers their only chance for economic survival rendered socialism anathema. A miniscule number of black activists were temporarily attracted to the party, however, including W. E. B. Du Bois and Hubert H. Harrison. Du Bois, the scholar-turned-editor and NAACP leader, first encountered socialist doctrines as a graduate student in Germany in the 1890s; by 1904, he would “scarcely describe [himself] as a socialist” but admitted that he held “many socialistic beliefs,” which included public ownership of railroads, mines, and factories.32 He joined the New York party local in 1911, but his flirtation with the Left was brief. With the approach of the 1912 presidential election, he voted for the southern-born Democrat, Woodrow Wilson (a decision he would come to rue). Although never overtly hostile to the socialists, he made clear his sharp disappointment with America’s white radicals. The party’s socialism was the “Socialism of a State where a tenth of the population”—some nine million “Americans of Negro descent”—is “disfranchised,” yet they “raise scarcely a single word of protest against it.” When “Revolution is discussed,” he asked, “it is the successful revolution of white folk and not the unsuccessful revolution of black soldiers in Texas”? For Du Bois, the answer was an unfortunately self-evident “no”. The nation’s silence—its lack of “moral courage” to discuss frankly the “Negro problem”—was shared by reactionaries and radicals alike.33

Hubert Harrison’s involvement with the SP was longer but his disillusionment even more bitter. A native of the Virgin Islands, Harrison made New York his home in 1900, completing his secondary schooling there and securing a position as a postal clerk. A voracious reader, an elegant and powerful writer, a trenchant social and literary critic, and a skilled and charismatic orator, he emerged as the Socialist Party’s most prominent and vocal black member by the early 1910s. His primary task, it seems, was to educate his fellow white socialists about the “Black Man’s Burden,” a subject that they knew little about and about which they expressed little interest. The facts he brought to their attention would “furnish such a damning indictment of the negro’s American over-lord as must open the eyes of the world,” Harrison wrote in 1911. Disfranchisement, segregation, a system of peonage that constituted a “second slavery,” and white trade unionists’ violent attacks against black workers were only part of his bill of complaint.34 These alone should have commanded blacks’ plight to white socialists’ attention. But lest his white listeners fail to be moved by his indictment, Harrison translated it into a language socialists could not fail to understand. America’s black population formed a “group that is more essentially proletarian than any other American group,” he insisted. Not only was the Negro “the most thoroughly exploited of the American proletarian, he was the most thoroughly despised.” The nation’s ruling class propagated race prejudice, the “fruit of economic subjection and a fixed inferior economic status.” Whatever else white socialists might think, they had to confront the fact that “the Negro problem is essentially an economic problem with its roots in slavery past and present.” Since the SP’s mission was to “free the working class from exploitation,” the fact that the “exploitation of the Negro worker is keener than that of any group of white workers” made it the duty of party members to champion the cause of African Americans. “This is the crucial test of Socialism’s sincerity,” he concluded.35

Socialists failed that test, Harrison believed. Recruiting black members required special efforts on the party’s part, including an acknowledgement of “their history, their manner of life, and modes of thinking and feeling,” as well as the deployment of multiple black organizers. The party did neither. Then there was its members’ behavior. The purpose of socialism was to “put an end to the exploitation of one group by another,” Harrison insisted. “We are not a white man’s party or a black man’s party, but the party of the working class.” But that ultimately seemed like wishful thinking, not a description of fact. From within the party, Harrison took his white comrades, particularly those in the South, to task for embracing “Southernism” over socialism. Shortly after becoming a party organizer, Harrison observed that “south of the 40th parallel are some people who think that the Socialist movement can be made into a vehicle for the venom of their caste consciousness.”36 Putting the question bluntly, he asked: “Is it to be the white half of the working class against the black half, or all the working class? Can we hope to triumph over capitalism with one-half of the working class against us?”37

Over time, Harrison’s frustration with the party’s unwillingness to make race as central as he would like prompted him to withdraw and channel his energies in other directions. In print, on Harlem soapboxes, and in meeting halls, the man known as the “Black Socrates” had, by 1915, left the party and resolved to give himself “exclusively to work among my own people.”38 Advancing a “race first” perspective, he published a short-lived magazine, the Voice, and led a short-lived Liberty League to promote racial consciousness and black political influence in 1917. Self-consciously portrayed by its founder as the foundation of the “manhood movement for Negroes,” the League vowed to organize blacks to vote independently and to advocate armed self-defense. Turning to the Socialist Party for financial support in 1917, Harrison could maintain neither the journal nor the League when it rejected his appeal. It was not that New York party leaders had no interest in supporting black radicals; it was, rather, that they had already committed funds to subsiding Randolph, his partner, Chandler Owen, and their newly launched magazine, the Messenger.39 Harrison’s bitterness toward the Socialist Party, and its leading black members, Randolph and Owen, intensified over time. The SP’s record, he charged in 1920, did not entitle its members to respect from blacks. “We say Race First,” he lectured them, “because you have all along insisted on Race First and class after when you didn’t need our help.” Now that the party had lost influence and membership, it finally seemed willing to take up blacks’ cause. “Well, we thank honest white people everywhere who take up our cause, but we wish them to know that we have already taken it up ourselves.” As for the Messenger’s editors whom the party had selected to represent African Americans, they were “green and sappy in their Socialism.”40

That the Socialist Party of the early twentieth century was not an attractive or promising vehicle for advancing black rights is a conclusion drawn by most historians interested in race, labor, and radicalism. Prior to the war, argued the socialist writer James Weinstein almost half a century ago, “Negroes were virtually ignored by the Party officialdom.”41 With a few exceptions, Sally M. Miller once observed, the Socialists “did not see the Negro[,] . . . doubted Negro equality[,] and undertook no meaningful struggles against second-class citizenship.”42 Not only did southern branches sanction segregated locals, but some of the party’s leading figures—like Victor Berger of Milwaukee—were open in their belief in black inferiority.43 Perhaps most significant, the party’s official program seemed to leave little space for the recognition of black Americans’ distinctive place within American society. In his 1903 essay, “The Negro and the Class Struggle,” party leader Eugene V. Debs declared that “We have nothing special to offer the negro, and we cannot make separate appeals to all the races. The Socialist party is the party of the working class, regardless of color.”44 In so declaring, Debs was hardly signaling disinterest in black recruits; rather, he was affirming a shared socialist belief that, ultimately, race prejudice was but a tool of domination deployed by the ruling class intent upon dividing and conquering; that black workers were workers whose problems would be solved by a common working-class strategy and program resulting in capitalism’s defeat. Socialism “recognizes no class or race distinction”; it “contains the only hope for either black or white,” white party member Charles H. Vail had explained in 1901. For black Americans, it would both “emancipate the negro from economic servitude” and would “solve the negro problem by destroying race prejudice” over time. Socialism was “the only hope for the negro and for humanity.”45 Unlike the Communists in the 1920s and 1930s who insisted upon the specificity of blacks’ oppression as workers and as a national minority under capitalism, the SP in its “daily functioning . . . did not concern itself with the Negro’s economic and political problems,” in Miller’s disapproving words.46

What, then, would lead Randolph, Owen, and a small group of other African Americans into the party’s ranks, given the SP’s apparently problematic stance? What prompted them to remain socialists as opposition from black nationalists and interracial communists intensified into the 1920s? Their following of a less-traveled and idiosyncratic path into the world of socialism initially came through books and personal contacts. Unlike Harrison or Debs, Randolph and Owen never held up the party’s race record to close scrutiny; instead, they took individual socialists’ positive expressions of support for black rights as evidence of the party’s overall progressive stance. After all, key white socialists like Mary White Ovington and William English Walling had been instrumental in founding the NAACP and, in the pages of the New York Call, the party’s daily, could be found sympathetic and at times extensive coverage of the plight of black Americans, particularly in the South.47

On a personal level, individual white socialists made a deep impression upon Randolph. If Debs once suggested that the party had nothing special to offer blacks, he also affirmed, on numerous occasions, his firm belief in black humanity and his deep understanding of black suffering. Neither his door nor heart would “be ever closed against any human being on account of the color of his skin,” Debs insisted in 1904. In a wartime exchange with a skeptical Du Bois, Debs displayed no defensiveness, only a general endorsement of the Crisis editor’s indictment of the American racial order. “The whole history of the American slave trade and of African slavery in the United States, clear down to the present day, is black with infamy and crime against the negro, which the white race can never atone for in time or eternity,” Debs passionately wrote. Chattel slavery was a crime “without a parallel in history,” for which “complete restitution . . . can never be made.” As for the socialists, Debs concurred that even among their ranks “the negro question is treated with a timidity bordering on cowardice which contrasts painfully with the principles of freedom and equality proclaimed as cardinal in their movement.” He forthrightly condemned the socialist “who will not speak out fearlessly for the negro’s right to work and live, to develop his manhood, educate his children, and fulfill his destiny on terms of equality with the white man.” That individual simply “mis-conceives the movement he pretends to serve or lacks the courage to live up to its principles.” Debs may have incurred Du Bois’s disapproval with his admission that the “negro is ‘backward’ because he never had a chance to be forward,” having been “captured, overpowered, put in chains, plundered, brutalized and perverted to the last degree.” But all that would change, Debs argued, if African Americans were given a genuine chance. “The negro is my brother. . . . I refuse any advantage over him and I spurn any right denied him.” In the end, blacks’ “salvation” lay “with themselves,” and through organization, self-education, and their assertion of “united power,” they would “progress” and “take their rightful place in society.” Nothing in his words suggested a subordination of race to class or a failure to recognize the specific conditions experienced by African Americans. It would be difficult to find a stronger indictment of America’s racial past and present and a more open embrace of the African American cause from any group of whites at the time.48

In the Messenger and in later recollections, Randolph expressed a deep respect for the white socialist leader. Although he did not consider Debs to be a “great leader of thought,” he did see him as a “matchless” and “mighty orator, one of the great men on the platform for social change,” who “had the power of moving people . . . by painting pictures of the degradation of the working man.” In a description that others would later apply to Randolph, he viewed Debs as “selfless. He had no concern about amassing wealth, making money out of anything he did.”49 Impressed by these attributes, Randolph admitted that Debs “had quite a bit of effect on me.” But the relationship went both ways. “Debs had great admiration” for the black socialists too, “because it was a new phenomenon to find Negroes leading in the Socialist movement.”50 The Randolphs spent “time with him,” dining together at various downtown restaurants and talking philosophy and politics in Harlem. At no point did Randolph perceive any racial condescension in their exchanges. Debs “was a man who was absolutely convinced of the principle of equality among human beings, regardless of race, color, religion or anything else. And he practiced it and he demonstrated it by his work.”51

Debs was not the only white socialist who favorably impressed Randolph.52 As Randolph took to soapboxes in Manhattan, he came into contact with the hitherto unknown but vibrant world of Jewish immigrant socialism and labor radicalism. The encounter was enlightening for both sides. “These people were really converted to us, because we were black,” Randolph later explained. “They had never seen any black people on a soapbox . . . this was altogether new to them.” The staff of the Jewish Daily Forward, in particular, found the young black radicals compelling. “They said, ‘I think you ought to be supported. You’re doing for our country that which ought to be done, that is, giving them knowledge about the history of man, the history of the struggle of civilization.” The Jewish socialists provided Randolph and the Messenger with modest financial assistance over the years.53 But more than money was involved. “All of us Negroes know that, on the whole, the Jews are the fairest and most friendly people in the United States in their dealings with the Negroes,” the Messenger declared in its first issue in November 1917. “Despised and oppressed through centuries, the Jews know what oppression means, and consequently they have always been tender and sympathetic toward the Negroes who have been their companions in drinking the bitter dregs of race prejudice.”54 In subsequent years, Randolph would appreciate the struggles of Jewish trade unionists in the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union; he would become a strong supporter of the state of Israel.

What, then, was socialism to Randolph? What, specifically, did he think it would do for blacks? Why did he think that blacks should vote for the party? Another reason that the Socialist Party drew Randolph’s support stemmed from his belief that neither of the principal political parties had anything to offer black America. With the pre–New Deal Democratic Party attracting little black support, he castigated the black electorate for its “slavish and foolish worship of the Republican Party,” whose sole gesture was granting the occasional patronage post to a few prominent black politicos while offering them “no voice in the government.” Those obedient “Negro peanut politicians”—“political palliators, acquiescers and compromisers”—did their white masters’ bidding. With “hat in hand,” the hand-picked black official, the “old, archaic, fossilized Negro political” parasite “sermonizes, prates and apps about the grand, old Republican Party being the ‘ship and all else the sea” in exchange for “a crum [sic] from the political dinner table.”55 The Republicans shared the blame for all that afflicted black America: “Jim Crowism, segregation, lynching, disfranchisement and discrimination.” And since the overwhelming number of African Americans were working people, they had “nothing in common” with the “party of plutocracy, of wealth, of monopoly, of trusts, of big business.”56

In the first issue of the Messenger, which appeared shortly before the 1917 mayoral election in New York City, Randolph put a positive spin on the Socialist Party’s race record. The SP “does not even hold race prejudice in the South,” the journal declared; the following year, it echoed that claim by declaring that the “Socialist party has always . . . opposed all forms of race prejudice.”57 Were the editors being disingenuous? Or were they ignorant of the party’s mixed record? Although they left no clues to help historians resolve the matter, it is possible to believe that their standard of evaluation was different than that of Du Bois or Harrison; that they simply did not judge the party as a totality; that they ignored the party’s practical shortcomings, and embraced the more progressive New York variant, which they very much found to their liking.

Whatever the case, the Messenger’s socialist pitch to black readers was largely class-based. Mayoral candidate Morris Hillquit would reduce the high cost of living; provide free food and clothing to school children “as a matter of right,” not charity; build public housing; eliminate food speculators by establishing public markets to sell fresh food to people “at cost”; end the practice of jailing war critics; and promote municipal ownership of subway, telephone, gas, and electric service. African Americans, who suffered from exorbitant rents, high subway fares, and the escalating costs of living, would directly benefit: The Socialist Party, the journal explained, “is the Party of the workingman” and “99 per cent. of Negroes are working people.” Hence, logically, blacks should vote the socialist ticket.58