Читать книгу The Least of These - Andrew E Matthews - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

LEPERS

ОглавлениеThe market was teeming with people as we searched and bargained for essentials. I impressed upon Shanti the need to spend as little as possible. In her kindness, she didn't ask why. She just kept bargaining, which she was doing when I was distracted by a small gathering around a man, an Indian, who appeared to be preaching. I wandered over to listen and found myself a subject of his attention. I was carrying the only food we would be eating for a while: a large bag of rice. Unwittingly I provided an illustration for him.

"Christians are told to forgive their enemies," the man was saying, a statement that was met with some derision and humour from his listeners. He was not an elderly man, but was greying at the temples, so reasonably advanced in years. I wondered what financial benefits he received for this preaching, which I suspected he must be paid by the foreign missionary.

"Your reaction is right," he acknowledged. "How is this possible? Like this man here," (and this was where I became the subject) "we all have a burden. We have a burden of guilt and unforgiveness that we carry."

I did not like the attention, but far more annoying were the words, words that quickly cultivated anger in my breast. I was no longer a dependent school boy who had no right of reply. I wanted to shout him down. How dare he presume that I, or anyone else, had burdens of guilt or unforgiveness? How quickly I had forgotten my own feelings from the day before. But now all that was eclipsed by my noble cause.

"But when Jesus takes that guilt and unforgiveness, then we too can forgive others because we no longer have that burden weighing us down," he continued.

I would have argued, confident of my right and the anger mushrooming inside me, except for what happened next, turning anger to fear in an instant.

A boy, a beggar, no more than ten years of age, was wondering through the crowds, begging and no doubt seeking opportunities to steal. And Shanti, having completed her purchase and carrying the bag of vegetables, turned to join me. I suppose neither was looking where they were going in that moment. They collided. Shanti, conscious of the baby she was carrying, reacted to protect her stomach and called out instinctively, a cry that caused me to instinctively swing to her defence.

The boy, malnourished, but also aware of his secret, had leapt backwards and lost his footing. I moved swiftly toward them and aimed a vengeful kick at the wretch lying on the ground. Apparently he was familiar with such treatment and he expertly avoided contact. But in doing so his hand, a hand that had been holding his buttonless shirt closed around his neck, was needed to balance his deft avoidance. In that moment his shirt fell open.

Somebody screamed.

My second strike swung from its target in an avoidance manoeuvre of its own as I swivelled instantaneously towards Shanti, the bag of rice toppling in the swiftness of my act. I let it go, precious grains erupting from the bag as it split, rice flooding onto the dirt.

My only thought was Shanti. I shielded her from the crush as people put as much distance between themselves and the boy. Shanti had not seen what I had seen.

"The rice," she called.

"Leave it. Leper."

Yes, I knew there was a cure for leprosy, but it hadn't been around that long and the stigma of a curse such as this lingers for many decades in the psyche of a people. There is something at the edge of my memory that I still can't quite grasp - perhaps it is only a feeling - but whatever it is, it causes me to baulk, even now, at the thought of leprosy. Times are changing, but back then, leprosy was still a curse in rural India. I think it is still so. Lepers are not readily accepted back in their communities, if at all.

The boy who had fallen and who was hopelessly trying to cover the appalling lumps and lesions on his shoulder and neck, was cursed with this sickness that above all others separates one from society, makes one an outcast, and an out-caste.

And we were closer than I wanted to be, on the edge of the wide circle that had formed around the boy, who was alone now on the dusty ground, staring despairingly at the crowd, they making the sign against evil, some shouting curses at him, others shouting at those pushing to see from the back of the crowd.

It happened in the middle of this chaos.

The clamour decreased, the crowd calmed, almost hypnotized it seemed, as a white man, a European in his fifties I guessed, stepped from the crowd. He stood looking at the boy for a moment - it seemed longer. Nobody spoke. He could not see the leprous lesions from the angle he had approached. He started forward.

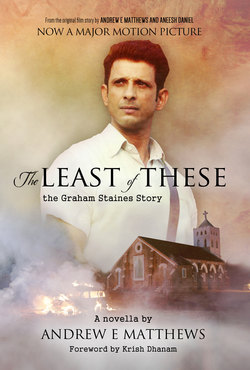

Of course it crossed my mind that this was the missionary - Staines was his name. An Australian. Apparently he had been in Baripada for over 30 years. He wasn't the fly in, fly out variety. He was more dangerous. You didn't stick with something that long unless you had carved out a very comfortable life, filled with servants and luxuries you could not enjoy in your home country, or you were of the really hazardous variety: a fanatic.

Nevertheless, the man was walking right up to a leper, a boy cursed with a terrible, contagious disease, the treatment of which was and is difficult and time consuming. I scanned the crowd - they seemed spellbound, fascinated, watching.

Shanti felt as I did; we didn't know, and Mishra had not mentioned this aspect of Staines, the missionary.

'Do something, Baba," she whispered.

I knew what she meant. I couldn't allow him, irrespective of who he was, to walk up to a leper unknowingly, even if everyone else was going to let him. It did make me wonder, fleetingly, if there was a suppressed animosity towards him amongst the people of this town.

I called out a warning, "Hey Mister, he's a leper."

He raised his hand in acknowledgement, but did not look my way, his eyes on the boy alone.

The boy turned at his approach, alerted by my call. His shirt fell open again and the full effect of the disease up his shoulder and across his chest was revealed. Shanti gasped. I quickly shielded her and tried to move her further away, but the crowd were not giving way at this climactic moment in the drama. I was angry with myself for not getting her away earlier. We were about to have a baby and proximity to a leper, looking at a leper, was asking for bad luck.

By this time Staines - yes, it was him, although I still wasn't certain at that point - had knelt down beside the boy and was talking to him. Then he did a thing that is still etched in my memory, something so foreign to my way of thinking that I could hardly grasp what my eyes were telling me. This man reached out both arms, took this boy in them and lifted him gently from the ground and held him close.

At that moment an experience from my youth on the streets of Kolkata flooded my memory in all its detailed and emotional clarity. We were walking on a busy street when my mother pulled me to the side, around a man lying in our way. He was moaning, trying to move, eyes glazed over from starvation and near death. My mother told me not to look, but it was a fascinating sight to a young boy. As I looked back at the man, I saw a small woman dressed in strange clothing kneel down next to him and begin to tend to him. Soon the sight was obscured by the throng of people, but the picture of humility kneeling next to pain, the depiction of compassion and hopelessness merging, that portrait was inexplicable, transcendent, 'other'. It was the only time I saw Mother Teresa.

The boy buried his head in the man's neck as he was carried from the scene. Then the crowd parted, and quickly too, clearing a wide pathway for this impossible sight to depart along. Had I just witnessed a phenomenal display of courage, or was the man simply insane? I asked who the man was, already knowing the answer.

"That was Graham Staines."

Yes, that was my first encounter, and it left me in no doubt that Staines was a missionary of the hazardous variety: a true fanatic.

But I had a job to do.

I should have done more research, been more cautious, but I didn't have the luxury of time. How is one to know that misfortune lurks just beyond the next bend in the river, ready to throw one in?

My investigations into Christian activity in the area had quickly borne fruit... although that is too generous a description. I had seeds that could be planted, an encouraging start en route to the garden of delights that I was anticipating: a baptism by Christians of a young woman was to take place at a nearby village and a number of the villagers were anxious and annoyed. The primary reason for the baptism appeared to be the promised marriage of the girl to a Christian boy. Why not convert the other way around? It did not take much on my part to fuel the villagers discontent into a commitment to action. The plan was for a group of men to ambush the baptism and prevent it from happening. I, of course, would be present, together with my impressive camera, to capture the evidence.

I had to leave the house well before dawn to reach the place. After a long walk I made my way through the riverside reeds to find a suitable hide, a spot with a view of what I hoped was the location where the baptism would take place.

At the time, I remember, I was excited. I expected a successful disruption of the baptism, good photos with the telephoto lens and an excellent article to hand in to Mishra. If luck was on my side, I thought, Staines would not only be present, but also conduct the baptism. I still had a lot to learn.

That early morning was filled with anticipation for me. Even the mosquitoes could not suck it from me as I huddled at the water's edge, the steam gently resting just above the surface of the water, beautiful lilies, kokaa, a scattering of pink along the banks, opening up as if offerings on my part to the Goddess of Wealth.

It was not long before the tell-tale put-put of a motorbike approaching interrupted my dreams of Mishra's pleasure and my inevitable success. I remained hidden, practising patience. I had the right place; all I had to do was wait for the action.

The small group of Christians gathered at the waterside exactly where I had expected, but there was no sign of Staines -disappointing, but not ruinous to my expedition.

I waited, camera ready, for the moment of disruption as a local pastor took the young woman into the water, snatches of his words reaching me across the water.

"...The way, the truth..."

"...Do you believe..."

I could not hear her replies.

"...Of your own free will..." (I remember being struck by that line).

But it was happening too fast.

I risked raising my head above the reeds, scanning for the promised villagers.

"I baptise you in the name of the Father..."

And in she went, disappearing under the water, and still no sign of the disrupters. What was I to do? When next would I have such an opportunity?

Impulse urged me to action.

I intercepted their retreat to the road, determined to question the woman and challenge the proceedings, nullify them if I could. My anticipation of an easy success had heightened my disappointment, which in turn fueled my anger and determination to get something worthwhile out of this event.

The Christians quickly closed ranks around their prize who was now wrapped in a blanket against the cold, shrouded in her new cloak of protection and supposed righteousness, they hustled her away from my approach and the reality I represented. The pastor intercepted my inquiry, turning to block my advance and prevent me from getting anywhere close to the girl. He was smiling, pretending friendliness. He didn't just smile; he couldn't stop smiling - at his victory, I was sure.

I moved to get past him, calling, "What have you been promised?"

He bluntly blocked my path again, making it quite clear that he would physically prevent me from speaking to the girl, as if that insolent smile of his was compensation.

"Only what God promises, Sir."

He had the impudence to call me "Sir" while still standing in my way, no intention of treating me anything like a "Sir". I tried to push past him.

"I want to talk to her."

"You can talk to me, Sir."

"Where's your legal documents? Your affidavit?"

"Those are for the proper authorities, Sir, not for you."

It was the "Sir" again that really did it, and the superior attitude. I grabbed the wooden cross he had hanging around his neck.

"You think this gives you the right? Huh?"

With my other arm I shoved, really only trying to get past him...

I'm still not entirely sure how it happened. I suppose I pulled harder on the cross as a counterbalance to the push of my other arm. And he tripped as he stepped backwards, adding to the weight. Maybe I even tried to stop him falling - I don't know - but I do know that the thin leather around his neck snapped, and I know I was pulling hard at that moment, and I know that the bottom point of the cross with its metal cap smashed into my camera lens, badly cracking that expensive lens.

It sounds like a cliché to me now, but I honestly could not believe my bad luck. My first report, and I had not even taken a photo yet. I could not imagine what I was going to say to Mishra. I could see the certainty of a permanent position fading fast.

It took me a while to realise the pastor had hit his head on a rock when he fell. He was being assisted by a young man from the group, now shirtless as he wrapped it around the pastor’s head to staunch the flow of blood. I vaguely heard “you may need stitches” as I tried to come to terms with my own tragedy; hardly a tragedy, but I was young and selfish, and that was how it seemed to me at the time. The first carefully cultivated opportunity for my garden of provision had been ravaged by a flash flood, the top soil carried away, leaving me with a few sick and straggly seedlings. In that moment I could not imagine how I was going to salvage the story, let alone rescue my reputation.

Ah, how experience of real tragedy changes perspective!