Читать книгу After the Past - Andrew Feldherr - Страница 9

1 Lives and Times

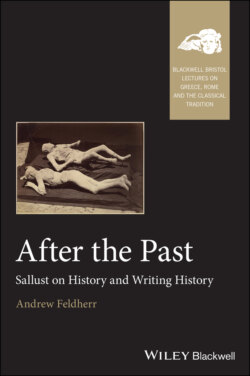

ОглавлениеI would like to introduce the approach to Sallust’s monographs developed in this chapter with an image, to be found on the cover of this book: a photograph by Giorgio Sommer showing the gesso casts of two bodies found on the Via Stabiana in Pompeii. I do so because the contrasting ways of understanding this photograph as a representation of the past at once figure the effects I want to claim for Sallust’s work upon its first audience and suggest their continuities with modernity’s experience of the classical world. My own initial impression of the photograph was of temporal distance. This derived from the already antique-looking sepia tones of the image itself, in conjunction with the battered and fragmentary aspect of the figures, and recalled to me the kind of self-conscious archaism so notable in Sallust’s diction. But if the picture looks old now, it was also clear how modern it must have seemed at the time it was made, around 1875. Had the casts simply been set against a black background, the effect might have been one of timelessness. But the way that background resolves into a cloth spread out on a pavement summons up the entire process of excavation and display. The very modern medium of photography, and indeed the technique of using plaster to fill the spaces in the ash the dead bodies had occupied, evokes the recent discovery of the figures themselves as part of a scientific program of exploration. Sallust’s emphasis on his impartiality and other evocations of the newly recuperated models of Thucydidean historiography give a similarly cutting-edge quality to his accounts of the past.1 The image comments on the promise of modern technology to capture history as it really was, with an objectivity no recovered work of art or ancient text could match. It is ultimately the combination of the sense of being in the presence of the real thing—and again at a moment of emotional exposure that strips away cultural difference—with a deliberate evocation of the distance that makes the past recoverable that I found so urgent in the image. A contemporary observer unwittingly highlights the same paradox when he comments on similar but earlier images that “while looking at the pictures, it is difficult to divest the mind of the idea that they are not the works of some ancient photographer who plied his lens and camera after the eruption had ceased, so forcibly do they carry the mind back to the time and place.”2

Again, the final scene of Sallust’s first monograph provides a specific point of comparison.3 His account of the corpses of Catiline’s defeated army combines a physical description of where they lay and the front-facing wounds on their bodies with an effort to depict the emotional forces that animated Catiline—Sallust’s words transform the breath his body still expels into the ferocity of spirit he had possessed while alive:

Sed confecto proelio, tum vero cerneres quanta audacia quantaque animi vis fuisset in exercitu Catilinae. nam fere quem quisque vivos pugnando locum ceperat, eum amissa anima corpore tegebat. pauci autem, quos medios cohors praetoria disiecerat, paulo divorsius, sed omnes tamen advorsis volneribus conciderant. Catilina vero longe a suis inter hostium cadavera repertus est, paululum etiam spirans ferociamque animi quam habuerat vivos in voltu retinens. … neque tamen exercitus populi Romani laetam aut incruentam victoriam adeptus erat. nam strenuissumus quisque aut occiderat in proelio aut graviter volneratus discesserat. multi autem, qui e castris visundi aut spoliandi gratia processerant, volventes hostilia cadavera amicum alii, pars hospitem aut cognatum reperiebant; fuere item qui inimicos suos cognoscerent. ita varie per omnem exercitum laetitia maeror, luctus atque gaudia agitabantur. (Cat. 61)

But when the battle was finished, then you might have beheld how much boldness and how much force of spirit had been present in the army of Catiline. For the very position which each while alive had fought to hold, his corpse was occupying even after death. A few in the center, whom the praetorian cohort had dislodged, lay at some distance, but all had fallen with wounds facing forward. Catiline himself was discovered far from his own troops amid the bodies of the enemy, still breathing a little and retaining in his expression the ferocity of mind that he had in life. … Nor did the army of the Roman people win a joyous or bloodless victory; for all of the most active had either fallen in battle or left it gravely wounded. Many who had come forth from the camp to look or to despoil, upon turning over the enemy corpses, discovered either a friend or a former host or relation; there were also those who recognized their own personal enemies. So diversely throughout the whole army exaltation and grief, mourning and pleasure were being enacted.

But it is not just the image Sallust represents that recalls the subject of the photograph. His narrative moves out from the corpses themselves to end with a view of the spectators coming out to see and take spoils from these bodies, and with an effort to evoke the emotions that “were being enacted” among the survivors as before he had done with Catiline. There is a big difference between looking at the image of an image of a 2000-year-old corpse in a museum on another continent and finding the real thing on a battlefield. But by making the last event in his narrative also the first event in its reception, Sallust highlights the layers of temporal and narrative distance between his reader and the actual scene. These layers can suggest separation, the 20 years from what we call 63 BCE to 43 and the distinction between a book and a body, or they can point to the stages that connect times and audiences. And to imagine an original audience for Sommer’s photograph brings a more immediate connection for us as well. As the nineteenth-century viewer was likely more aware than we, photography was a physical process only possible in the direct presence of what it depicts. The man and woman in the image left a material trace of remarkable intimacy on the volcanic matter that killed them. The gesso mold can only be made by putting the plaster into contact with that substance. The photograph can only be made by a long exposure to the mold. And one important use of these images was as souvenirs, which travelers could take back with them from their visit to the site. From this perspective, these inescapably modern images seem less depictions of antiquity than direct traces of antiquity. So too in the case of the Sallustian narrative, the distance that makes historiographic representation possible competes with an impression that the narrative itself is produced by the events it describes. His history becomes a fragment of the past, not so much removed from time as embedded in a process of transformation that can be traced within time.

This final effect of Sallust’s narrative, where the past at once recedes from and approaches the historian’s audience through a recognition of the text’s participation in time, provides my own starting point for interpreting his work. It is also the point of my title, “After the Past,” which intends to capture the same tension between distance and contiguity linking now and then. The complexity of Sallust’s positioning his audience in time can be first described through the tools of narratology, as in Jonas Grethlein’s holistic interpretation of all ancient historiography, informed by the modern struggle between what he calls teleology and experience as goals for historiographic representation. Teleological narratives lay emphasis on the hindsight available to both author and reader. Such depictions fit events into a larger story whose ending point lies beyond what any of the figures in the narrative can know and so inevitably separate the perspective generated by the narrative and those of the actors within it. By foregoing an effort to explain events, however, historians can much more directly reproduce the experience of the past.4

Grethlein’s demonstration of how a historical narrative generates this division in points of view, for example, through effects like counterfactuals, which construct a future in the past different from how the reader knows things will always turn out eventually, leads him to quite surprising re-evaluations of the ancient historians. Yet while narratology offers an excellent and precise tool for describing these effects, it does not on its own suffice for explaining them. Narratology recognizes, indeed practically develops from the recognition, that descriptions of internal spectators or focalizers refract representations in the ways I have been discussing, but such descriptions also do something more. They draw attention to the very process of spectation and response and, by embedding it within their own narrative, interpret it. And so starting from this very up-to-date—I am tempted to say photographic—account of what Sallust does I want to ask more directly why he is doing it. How does his account of Roman history explain why it matters whether his work draws his reader closer to events or imposes distance? And what historical and cultural factors are likely to have made such choices meaningful for his contemporaries? In this chapter I suggest how three aspects of Sallust’s work can be connected through their mutual dependence upon a reader’s recognition of the narrative as a representation of the past or as a part of history. These aspects are, first, the larger temporal framework employed to locate events and to measure the distance between present and past; second, the consequences of such perceptions for the audience’s conception of their political present, whether they see themselves as part of the res publica or as outside, and after it. My final subject will be the historian’s own language and whether it can represent change or must be affected by it. Befitting my attempt to keep the historicity of Sallust’s writing before our eyes at the same time that we try to understand his own view of history, I will try to locate my interpretations within the time period in which Sallust wrote by making comparisons to the literary production of a precisely contemporary figure, Marcus Junius Brutus, born just one year after Sallust. And since his work is almost completely lost, no one will mistake my efforts at historicization as anything more than subjective prompts for reimagining the effects of Sallust’s writings.

I begin with a couple of preliminary observations to confirm that the audience’s sense of where they stand in time is an issue that matters in Sallust. First, that partial viewpoint of an immediate audience in the final sentence of the Catiline gains yet further power by contrast with the work’s opening. Sallust begins the monograph with a description of omnis homines—all humans, not particular humans, nor even Romans—and treats them as objects of description more than as subjects: what men ought to do turns out to be very different from what they actually do. The verb of that sentence is also in the present tense, implying not so much that the claim he makes is true “now,” but that it is always true:

Omnis homines qui sese student praestare ceteris animalibus summa ope niti decet, ne vitam silentio transeant, veluti pecora quae natura prona atque ventri oboedientia finxit. sed nostra omnis vis in animo et corpore sita est: animi imperio, corporis servitio magis utimur; alterum nobis cum dis, alterum cum beluis commune est. quo mihi rectius videtur ingeni quam virium opibus gloriam quaerere, et, quoniam vita ipsa qua fruimur brevis est, memoriam nostri quam maxume longam efficere. nam divitiarum et formae gloria fluxa atque fragilis est, virtus clara aeternaque habetur. (Cat. 1.1–4)

All human beings who desire that they stand ahead of other living creatures ought to strive with the greatest effort not to pass through life in silence as the herds, which nature has formed as downward looking and subservient to their stomachs. All our power is placed in mind and body; we employ the ruling power of the mind, the slavery of the body. The one we share with the gods; the other with beasts. Therefore, it seems more upright to me to seek glory with the resources of talent than strength, and, since the life we enjoy is short, to make the remembrance of us as long lasting as possible. For the glory of wealth and beauty flows away and breaks; virtue is held (as) bright and eternal.

A glance back at the work’s beginnings from its ending makes clear how it has combined a focus on a specific point in time with the fragmentation of perspectives that lead from all humans to the partial and partisan view of the battlefield; as I will discuss more later, this process takes the reader into history, both as a genre and an awareness of how one’s place in time affects perception.

My second point moves from narratology’s concern with point of view to the schemata the text creates simply for measuring and understanding time. In a narrative like Livy’s, structured around changing years marked by naming consuls, you always know where you stand.5 Even if consular dating provides a notoriously awkward system for relating events to one another, for visualizing the hundred years between the defeat of Hannibal and the defeat of Jugurtha, it creates a powerful sense of a shared experience of the past measured through Roman political institutions. Sallust too seems to mark this tradition by beginning the first action of the story of the conspiracy proper with a specific consular date, the Kalends of June when Caesar and Figulus were consuls (17.1). But as the notice that this is June 1, not January, may suggest, we are already in medias res. For Sallust has provided his own account of the first beginnings of the conspiracy and located them in two contrasting frames of reference for understanding time. First, these events which we could measure from the middle of the consulate of Caesar and Figulus become manifestations of causes better traced through the life story of Catiline, and Sallust similarly imposes a biographical structure to his narrative, by beginning the story of Catiline at his birth and ending with his death. These causes must also be explained by a longer digression on the development of the republic, one that does not emphasize its extent through the proliferation of named magistrates but collapses that history into a short story. Its pattern moreover seems not distinctively Roman but comparable to what other empires have experienced.

But Sallust’s use of consular dating not only contrasts the shared Roman convention for measuring the extent of time with the alternatives of a life story and a universal pattern of rise and decline. The consular date is itself made part of the narrative in a way that connects its use with a sense of belonging to the res publica. Catiline’s plot aims at his obtaining a place for himself in the Roman fasti by becoming consul. When Catiline outlines his plans for the future, beginning with the programmatic “new accounts,” he ends with the promise that he as consul, with his partner Antonius, will make a beginning of action, of doing:

tum Catilina polliceri tabulas novas, proscriptionem locupletium, magistratus sacerdotia rapinas alia omnia quae bellum atque lubido victorum fert. praeterea esse in Hispania citeriore Pisonem, in Mauretania cum exercitu P. Sittium Nucerinum, consili sui participes; petere consulatum C. Antonium, quem sibi collegam fore speraret, hominem et familiarem et omnibus necessitudinibus circumventum; cum eo se consulem initium agundi facturum. (Cat. 21.2–3)

Then Catiline promised cancelation of debts, the proscription of the wealthy, magistracies, priesthoods, plunder, and all the other things which war and the pleasure of the victors brings; besides, Piso was in Nearer Spain and P. Sittius Nucerinus in Mauretania with an army, both fellow conspirators; C. Antonius was also seeking the consulate, whom he hoped to have as a colleague, for he was both a close friend and a man beset by every sort of need; he himself as consul with this man would make a beginning of action.

Here is a counterfactual consular date that would provide not only the beginning of an ideal historical subject, a deed, but perhaps would restart a new res publica. Sallust’s choice of the conspiracy as a subject depends on “the newness of the crime and the danger.” Newness here implies a contrast with the old, with the Roman past constituted as a norm to measure Catiline’s exclusion from its traditions. But the Catilinarians themselves view time differently in looking not backward but forward to this new beginning. The conspirators see the promise of living after the past as positive good. And we may contrast Cicero’s efforts to ensure that any sense of the conspiracy as a new beginning was contained and refuted by his own consular insistence on precedent (cf. Cic. Cat. 1.3–4). Far from being really new, Catiline was just another rebel, with all too many antecedents in the early republic, each checked by the appropriate consul. And so the defeat of this conspiracy is both assured by the past and destined to take its place “in the date of my great consulate” (Juv. 10.122), within the ongoing flow of time that the open annalistic form guarantees. The consul, and consular dating, equally defeat Catiline.

Mention of Catiline’s implicit promise to refound the republic provides an appropriate cue for the entrance of the actual liberator, Marcus Junius Brutus. I will later return to Brutus’ potential similarities to Catiline, but for now I want to compare him not to the work’s protagonist but to its author. It may seem that Brutus can best illuminate Sallust by contrast: Brutus was an active figure who aimed to free the republic through his deeds; Sallust can be a historian because he already possesses a “free mind,” animus liber, one achieved through his own escape from the partisanship of the republic (Cat. 4.2). However, like so many of his contemporaries, Brutus also managed a varied and extensive literary production.6 And the particular works he wrote, historical epitomes, epideictic works, including a life of the Younger Cato, and philosophical treatises on duties, virtue, and endurance, echo precisely the generic alternatives that especially complicate a sense of time in the Catiline. Is Sallust’s work an excerpt from Roman history, an epideictic life of its protagonist, or a treatise on virtue? The accomplishments of Brutus the author remind us that these were no abstract categories but important and proliferating forms of literary composition in the decade when Sallust worked. Sallust places his Catiline between all these writings, offering each as a competing template for understanding his own priorities. But a focus on Brutus also allows us to measure the aims of these literary exercises together, to give a snapshot of what writing at Rome was for, and to make clear how all these forms themselves mirror different understandings of the relationship between past and present.