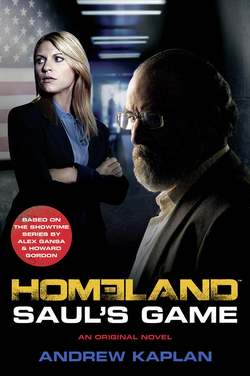

Читать книгу Homeland: Saul’s Game - Andrew Kaplan - Страница 16

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 8

Tampa, Florida

14 April 2009

That morning, Saul Berenson, CIA Middle East Division chief, publicly reprimanded at a meeting the previous day by the vice president of the United States, William Walden, and on official administrative leave, woke from a dream he hadn’t had since childhood. He was alone; the house silent, empty.

His wife, Mira, was gone. Back to Mumbai, India, two days earlier. If anyone asked, it was because of her mother’s illness, and to deal with the issues of Human Rights Watch, the charitable organization chapter her family ran. In reality, it was because she and Saul barely spoke anymore. There’s the official and the unofficial story in marriages like everything else, Saul thought as he dressed and packed for the airport.

Sandy Gornik, an angular, curly-haired up-and-comer from the Iranian desk, took time from the office to drive him to the airport. During the drive, Saul let it slip that he was going to Mumbai to spend some time with his wife and her family.

“Have you been there before? India?” Gornik asked. He had heard about Saul nearly getting fired. Nearly everyone in the NCS (National Clandestine Services), certainly everyone on the fourth floor at Langley, had heard about it. The story was topic A in the cafeteria. In fact, Sandy suspected he was probably not doing himself any good, careerwise, driving Saul to the airport.

But Gornik was one of Saul’s Save-the-Dead-Drop band, a tiny group, some four or five wise-ass, mostly single-rotation ops officers who picked up crumbs of tradecraft Saul dropped as he scurried through Langley’s anonymous corridors going from what he called “one moronic meeting to those where the Washington art form of wasting time reaches absolute mind-destroying perfection.”

“Once,” Saul said to Gornick. “Indian families are … well, it’s like getting into bed with a tribe of octopuses. No matter which way you turn, there are arms everywhere. Trust me, it isn’t simple.”

“I’m sure your wife and her family will be glad to finally spend some time with you,” Gornik said, hoping that came out right, that he didn’t sound patronizing or like he knew Saul had been involuntarily pushed out to pasture.

“I’m not so sure,” Saul said.

It caught Sandy Gornick, who always knew what to say to catch the female GS-8s and -9s trolling in Georgetown pubs, but not the real thing to someone who until yesterday had been not only his boss’s boss, but something of a force, if not yet a legend, in the Company, off guard.

“Sorry,” he said, face reddening.

“So am I,” Saul said, looking out the window at the traffic on the I-395, and that was that.

Cover established.

Saul thought he would prep for his next meeting during the two-hour flight from Reagan International to Tampa, but instead he kept his laptop closed. Officially, he was on leave. Officially, I don’t exist, he thought, looking out the plane’s window. Below, there were only wisps of clouds, and far below, the rolling green and brown hills of North Carolina.

Suspended in midair. Disconnected. A perfect metaphor.

He wondered if he would ever see his wife, Mira, again, because he certainly wasn’t going to India. He wasn’t even sure he would ever see Langley again. None of that mattered now. All that mattered was Carrie’s intel. It had changed the equation. It was about to change everything the United States was involved with in the Middle East.

The dream.

It had come back. For years, he’d had it almost every night as a child. And then one day it stopped. The day after he told his father he didn’t want to go to the old Orthodox synagogue in South Bend, the nearest to Calliope, anymore. He didn’t want to be Bar Mitzvah. And his father just looked at him, took his mother in the car, and, leaving him standing there, they drove off to the shul in South Bend without a word. Nothing. As if to say, Have your own war with God, Shaulele. You think because you say so, this is the end of the matter? You think God has nothing to say too?

Not a dream. A nightmare. He was a little boy in a ghetto somewhere in Europe. It was like some old black-and-white World War II movie, only it didn’t feel like a movie. He was there. It was night and he was hiding in an attic. The Nazis, the Gestapo, were hunting him. He had heard someone talking, and even though he didn’t understand the language, he understood they were informing on him. The Nazis knew he was there.

They were searching the lower floors of the house, coming closer. He could hear their dogs, German shepherds, panting, coming closer. Closer. He didn’t know where his parents were. In the concentration camps. Gone. Alive? Dead? He didn’t know. He didn’t know where anybody was. All the Jews were gone. He had been alone for days, weeks, without food. Living like a rat. Scavenging food from trash in the alleys at night; licking water from dirty pipes in the coal cellar. But now somebody had told on him and they were coming for him.

The Nazis were talking in German, a language he didn’t know, although it was close enough to Yiddish that he got a sense of it. He was so afraid he couldn’t move. One of the dogs barked twice, very loud. It was close. Too close, just on the other side of the closet door. Suddenl, the door opened and light spilled in.

“Heraus!” one of the soldiers shouted. The soldiers had rifles, but the ones he truly feared were two men who wore black leather overcoats with swastika armbands and death’s-head insignias on their caps. The soldiers yanked him out and smacked his face so hard he saw flashes of light and the room spun. They were shouting and yelling at others as they hauled him down the stairs.

When they got outside in the street, they kicked him and stood him facing a brick building with two others, a young woman with blond Veronica Lake peekaboo bangs, wearing a jacket with a yellow Jewish star on the pocket over a nightdress. She was shivering. Next to her was a little girl. The young woman and the little girl held hands. The little girl was crying.

The three of them stood in the only light, the headlights of an army truck. A stream of exhaust came from the tailpipe of the truck.

One of the Gestapo men in a black leather overcoat came over to the young woman. Saul noticed for the first time how pretty, no, much more, stunning, she was. Like a movie star. The German took out a Luger pistol.

“I’m pretty. I’ll do anything you want,” the young woman said.

“Yes,” he said, and shot her in the head. The little girl screamed. He shot her too, but it seemed to Saul that her scream didn’t stop. Although she was dead—he knew she was dead. She had to be; he could see the blood streaming from her head on the cobblestones—her screaming went on in the dark street.

The German came to Saul and pointed the pistol at his head. Saul could feel the muzzle just touching his hair. The German started to squeeze the trigger. Saul couldn’t help himself. He began to pee. It was always at that moment that he would wake up, the bed wet, smelling of urine.

He never told anyone about his dream. Not his parents, not even when they scolded him about the bed-wetting. His parents never spoke about the war, the Holocaust. Once, when he was eleven, he started to ask. His mother just turned away. His father pretended not to hear.

The second time he asked, his father told him to come with him. They were going on a trip.

They drove all the way to Gary, Indiana, to the big steel mill on the shore of Lake Michigan. There was a platform where visitors were allowed to stand and watch the molten steel being poured from the giant bucket. They watched the fiery display of sparks and felt the heat of the blast furnace on their skin. His father held his arm tight like a vise.

“You see that fire, Shaulele? First you stand in that fire. That fire. Then you ask me about the camps, farshtaysht? Because in that place, Shaulele, the place you’re asking, there was no God.” They drove home in silence and never spoke of it again.

So he didn’t tell them about the dream. He never told anyone. Except Mira.

He told her the night when, as a young CIA operations officer in Tehran in 1978, the Revolution turning too dangerous for her to stay in Iran any longer, he sent her back to the States.

They argued. She didn’t want to go. She accused him of wanting to be apart from her, of wanting her to go. She knew better. It was all around them. Even their friends talked about what was happening every day. What Saul couldn’t tell her was that his friend and best intel source, a former SAVAK officer, Majid Javadi, had warned him, that it was time for all foreigners, especially Americans, to get out of Iran. Still she refused to go.

That night in Tehran in 1978, for the first time since he’d been a child, the dream, the nightmare, came again. He had been moaning in his sleep, Mira said. That’s when he told her.

“I forgot. You were the only Jews in this little town in Indiana, surrounded by Christians. Were they mean to you?” she asked, putting her hand on his arm.

“Sometimes. Sometimes kids called me ‘dirty Jew’ and ‘Christ killer’ or they would look at me funny. One of the teachers said something and they left me alone. I spent a lot of time alone.”

“Little Saul, by himself on the playground,” she said.

“Look, it’s not like Hindus and Muslims in India, Mira. The Christians didn’t try to run us out or burn crosses on our lawn. I was an American kid. That’s all I ever wanted to be. The fear came from someplace else. My parents never spoke about what happened to them in the Holocaust. Never,” he said.

“Why are you telling me this?” she asked.

“Because last night, for the first time since I was a child, I had that dream,” he said.

“What does it mean?”

“You have to go now. It’s a warning. Something terrible is coming,” he said. As soon as the words came out of his mouth, he knew it was true.

Barely speaking to him, she got on the plane. A month later, it was Javadi himself who would teach him how terrible—and how true.

A very fit-looking African-American in his early forties in pressed slacks and a well-fitted casual shirt, hair cut short in a military high-and-tight, stood waiting in Tampa Airport by the luggage carousel. He was dressed as a civilian, as Saul had requested.

“Mr. Berenson, sir?” he asked.

“You are?” Saul asked.

“Lieutenant Colonel Chris Larson, sir. Can I take your bag?”

“I’ll take it. They told you to look for the guy with the beard?” he asked as they walked to the parking lot.

“Something like that, sir.” Larson smiled.

As they got into the car and drove on the airport road, Saul asked:

“Will it take us long?”

“It’s not far. You’ll be sitting in the general’s office in nine and a half minutes, sir.”

“The general likes it precise, does he?”

“He does, sir.”

They drove to the gate at MacDill Air Force Base, and nine and a half minutes, almost to the second, later, Saul was able to park his suitcase in the outer office and was sitting next to his carry-on in the office of four-star General Arthur Demetrius, CENTCOM commander, famous for having implemented the surge in Iraq, the current commander of all U.S. military forces in the Middle East, and in charge of all military-related activities and negotiations including the Status of Forces Agreement and the military resolution of the war in Iraq.

Demetrius was about Saul’s height, six feet. Lean, very fit, about fifty, with an intelligent horsey face, tanned from spending time outdoors. Not just West Point, Saul reminded himself. He had an M.P.A. from Columbia and a Ph.D. in political science from Princeton. He remembered Bill Walden’s description of General Demetrius. “He’s not just some military hard-ass. He listens.”

“So, Mr. Berenson, you know my problem?” Demetrius began, leaning forward on his desk, fiddling with a ballpoint pen. Behind him, Saul could see a bit of the air force base and a palm tree through the office window’s partially closed venetian blinds.

“Your problem is that Abu Nazir, IPLA, knows everything your troops or the Iraqis are going to do before you do. So do the Shiites and the Iranians. They’re always one step ahead of you. Your problem is that the U.S. is on the verge of an economic meltdown and the Congress and the country think the war in Iraq is over, only nobody told the enemy. Meanwhile, we, the CIA, have been playing Whac-A-Mole with IPLA and AQI, al-Qaeda in Iraq, not to mention the Shiites, and have been of little or no use to you. That’s your problem. Oh, call me Saul, General,” he said.

“Finally.” Demetrius smiled, putting down the pen. “Somebody from Langley capable of telling something that resembles the truth.”

“There’s more,” Saul said, and told him about the SOG mission to Otaibah and Carrie’s intel. When he talked about the SOG mission, Demetrius went to a wall map and they followed the mission on the map and then Carrie’s route in Damascus and to Aleppo.

“So the Syrians gave sanctuary to Abu Nazir?” General Demetrius asked. “Why?”

“So that Sunnis in Damascus don’t start strapping on suicide vests or RPGs with President Assad and his generals as the target,” Saul said. “Anyway, Abu Nazir’s gone. He’s not in Syria anymore.”

“So where is he?”

“Probably back in Iraq.”

“Any idea where?”

“Could be anywhere, could be south, even north.”

“Why? The Kurds’d have him for breakfast.”

“Hard to say. The one thing we’ve learned is not to underestimate him.”

“But you’ll find him?”

“Eventually. Right now that’s not my priority,” Saul said, moving his chair closer to the general’s desk. “Or yours either. You’re leaving very shortly, aren’t you?”

General Demetrius nodded, looking at him sharply.

“How did you know that?”

Saul pointed to himself. “CIA, remember? Listen, I came to you because it’s vital.”

Demetrius put down the ballpoint pen and leaned forward, his chin resting on hands clasped together as if he were praying.

“I’m listening.”

“I’ve been suspicious of something for a long time. Our ops officer in Otaibah and Damascus came through with intel that confirms beyond the shadow of a doubt that we have a mole. The likelihood is that it’s a very high placed mole somewhere within the Coalition Forces or top echelons of the Iraqi government. But I need to be absolutely honest and clear. It could also be inside the CIA’s Baghdad Station or even at Langley. It could even be inside your own command, General. It is one hundred percent actionable intelligence.”

“Inside my command?”

“Or mine, General. I don’t think it’s likely that a CIA agent or an American soldier would do such a thing, and none of us likes to think it’s possible, but you and I both know, sir, it’s been known to happen.”

General Demetrius stood up. He began pacing up and back in his office, then turned to Saul.

“What the hell am I supposed to do? We’re on the verge of making critical decisions to finish this war. I have to trust the people I work with, that I give orders to.”

“It’s worse than that. The same actionable intel also indicates that Abu Nazir is planning a major ‘action,’ something that may finally trigger the civil war you have been doing everything in your power to prevent, General,” Saul said, rubbing his beard.

“Do you know what it is?”

“Not yet. But I will. Very soon.”

General Demetrius glanced at his watch.

“We have three and a half minutes, Saul. Then I have to go.” He leaned against his desk. “Why don’t you tell me why you’re really here?”

Saul smiled. “They said you were good, General. I have to get going too,” he added, standing up and lifting the handle on his carry-on. “I need a favor.”

“And that is?”

“A counteroperation to block Abu Nazir’s action is being set up. I may—repeat may—have to come to you at some point for some Special Forces–type resources. Not sure if and not sure how much. Anyway, just in case, the name for this counteroperation is ‘Operation Iron Thunder,’ ” Saul said.

“And flushing the mole is part of this operation?” Demetrius asked, heading for the door.

“You could say so,” Saul said, following him to the outer office, where a half-dozen officers stood ready for the general. “You could definitely say so.”

General Demetrius stopped.

“And do you know where I’m going now?”

Saul smiled. “You’re flying, along with some additional resources, on your specially fitted C-17 to CENTCOM HQ in Doha, Qatar. Actually, I’m headed to the Middle East myself. Only not to Qatar.”

“Would you like a lift? I think we need to continue this conversation,” General Demetrius said.

“I was hoping you’d ask,” Saul said as a master sergeant grabbed the handle of his suitcase and pulled it after them outside the office toward the general’s waiting staff car.

The C-17 was bigger than any aircraft Saul had ever flown in. Both sides of its cabin aisle were fitted with rows of screens and electronics, which enabled the dozens of officers and men working at their stations to track the latest data from land, sea, and air operations from all parts of General Demetrius’s widespread command across the entire Middle East and South Asia. For several hours out of MacDill, an F-16 fighter jet flew escort, then peeled off when they were well out over the Atlantic.

Saul sat toward the rear, in an area of seats that were set in rows like business-class seats in a normal passenger jet. He worked on his laptop, doing tradecraft, setting up basic drops, codes, locations, for Operation Iron Thunder. He used special CIA encryption software that was unique to CIA Top Secret Special Access files; it could not be decoded by standard NSA, DIA, or other agency decryption software, not even by other CIA decryption software.

Two hours out, Lieutenant Colonel Larson, looking much more in his element in a Class-A uniform, came and asked if Saul would like to join the general for coffee. Saul followed him forward past the men and women working at their screens, talking through headsets to their counterparts in various commands, to the general’s office. It was completely closed off. Inside was an office with a desk, conference table, armchairs, and a lounge area with a stocked bar, all of it modernistic and made of stainless steel; it had the odd feel of a men’s club for robots.

General Demetrius was sitting in a swivel armchair, sipping coffee and reading a copy of the Economist, which he put down when Saul came in. He poured Saul a cup of coffee.

“How do you take it?”

“Milk and sugar; you take yours black, thanks.”

General Demetrius swiveled toward him, hands on his knees like a sumo wrestler about to pounce.

“You’re setting up a separate operation outside Langley, aren’t you? That’s what this little trip is all about, isn’t it?”

Saul sipped his coffee.

“Good coffee. I’m here so you could ask me that.” He looked around the partitioned office. “No bugs I hope.”

General Demetrius shook his head.

“You are worried. Who else knows about this?”

“The director of the CIA; the vice president, Bill Walden. Took him by surprise, but he finally agreed. Facts are facts. The national security advisor, Mike Higgins. The president. Now you.”

“Where are you going to run it from?”

“I’ll be moving around. But I’ll have something in Bahrain,” he said. “The capital, Manama. For obvious reasons.”

“Middle of the Persian Gulf. Not that far from Iraq. Or CENTCOM. Or Iran, for that matter. Like the real estate people say: location, location, location. Or do you have some thing or some one particular in mind, Saul?”

“Both maybe. Manama’s a crossroads. A place where people come to do business, clean and dirty. And close enough to your headquarters in Doha, General, although I suspect you won’t be there that often.” He put down his coffee.

“You know damn well I won’t be sitting on my ass there,” General Demetrius growled. “There’s a battle shaping up in Basra right this minute—and we don’t have shit there.”

“It’s not just IPLA. The Kurds, the Shiites, the Mahdi Army, the Iranians …” Saul ticked them off. “Abu Nazir is trying to light a match. There’s plenty of tinder lying around.”

“How soon and where?”

“I’ll let you know very soon,” Saul said, looking at the map of Iraq on the general’s laptop screen. “There are some things I have to do first.”

General Demetrius looked at him.

“Operation Iron Thunder?”

Saul nodded.

“Where do you start?”

Stand in the fire of a blast furnace to get the answer in a place where there is no God, Saul thought, for some bizarre reason thinking of his father. “By sending my best operations officer into the enemy’s camp with a big fat target painted on her back,” he said.

“What?”

“Sorry. A stupid metaphor. We don’t just know we have a mole who’s feeding AQI, General. For the first time, we also have a lead that might help us nail who it is. There’s more. The Iranians. They may be also be getting intel.”

“You’ve been reading my DIA reports. There’s something going on with the Iranians. The Shiites in Iraq have suddenly gone quiet. Too quiet. If our withdrawal from Iraq were to come under heavy enemy attack, it could be a bloodbath,” General Demetrius said grimly.

“What if we were to come under attack from both sides, the Sunnis and the Shiites at the same time—and they know everything you’re going to do in advance?”

“You must be a mind reader. What the hell do you think has been keeping me up at night?”

“I have a plan,” Saul said.

“Iron Thunder.”

“Exactly. I understand you play Go. Something of a fanatic, they say,” Saul said, taking a board and a box of black and white stones out of his carry-on. “You can be black. If you like, I’ll take a modified komidashi.”

General Demetrius studied him. “Are you hustling me, Saul?” He glanced at his watch. “Are you sure? The game’ll take at least a couple of hours.”

“No,” Saul said, waiting for the general to play his first stone. “Not that long.”