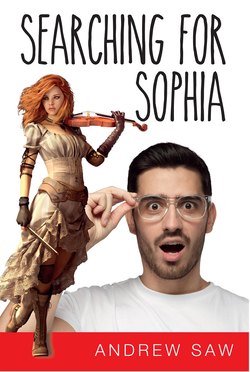

Читать книгу Searching For Sophia - Andrew Saw - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

It’s said real lovers don’t just meet, they’re a part of each other all along. Maybe it’s their dateable DNA. I’m not sure. What I can tell you is that when the violinist Sophia Luca walked out of my office in Elizabeth Bay, my business partner Dr Joe Franken was stunned.

“Definitely didn’t see that coming,” he said, as she left the building.

“See what coming?”

“You heard her. She had this weird feeling we’ve known each other forever, practically since we were kids.”

“A little unusual, so?”

“I know it’s bizarre but I felt the same thing.”

“Well, it’s nice being noticed by talented women.”

“So now I’m Harvey Weinstein?”

“Joe, you know I didn’t say that, but you’ve never seen her before, right?”

“Never.”

“So how does that work?”

“I wish I knew.”

I’m Dr Tim Wilde. For twelve years Joe and I have run a successful veterinary practice on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour, about a ten-minute drive east of the Opera House. Elizabeth Bay is an unusual suburb, both shabby and elegant like an elderly courtesan who has seen better days. To the west along a low ridge, her streets run into the drug confusion and retail sex of Kings Cross. To the east, she’s a haunt of elegant 1930s apartments and Georgian terraces, with the occasional mansion rolling its lawns down to the wintergreen harbour.

It rains cats and dogs in Elizabeth Bay, along with light showers of guinea pigs, goldfish, rabbits, snakes and budgerigars, so Joe and I are doing okay. We’re both single, in our late thirties, living in good apartments with harbour views. We drive nice cars and travel abroad whenever we feel like it. All we’re really missing is the right woman to love.

We’re devoted to the animals, of course, and our work is important but, with the exception of the odd anorexic axolotl, our practice rarely encounters anything exotic. Wandering between the strip joints and organic grocers you’re unlikely to be run down by a yak. On the other hand, if your guinea pig is buffing its claws and staring at you with an unpleasant look in its eye, Franken and Wilde is there to offer help. Although, as Joe never stops saying, “We’re not just treating animals, Tim, we’re treating whole families. Living things that keep other living things as pets need affection.”

Some of our customers dote on creatures that slither in cold blood, but it’s animals who pack or flock in nature that fall in love with their humans. They love like we do, with an attachment similar to that of human babies for their mothers. I’ve learned more about unconditional love from my feathered and furred patients than I have from any human. They’ve also taught me how terrible life becomes when devotion is ignored.

A nurse named Charlotte and her pet parrot were a case in point. Michael Hutchence was (and still is) a sulphur-crested cockatoo deeply in love with his human; and like all parrots, a passionate animal. His seventy-year life span and lifelong mating in the wild made him obsessed and possessive in captivity. Charlotte was freshly remarried in her early thirties with two small boys, and in Michael’s cockatoo mind they’d been in love since she was a little girl. They’d shared the homework, the hockey, the eisteddfods, every teen crisis, her difficult divorce, even the birth of her children. But the new man in her life made Michael simmer with jealous fury. When Charlotte and her husband wanted more out of love by candlelight, Michael would fly to the top of the bedroom cupboard and peer through flickering shadows with a baleful black eye. As soon as her husband’s back was uppermost, he would swoop, a parrot out of hell landing talons first, biting and tearing at bare flesh.

The strain on Charlotte’s marriage was considerable, but she couldn’t give up the parrot she’d loved since she was eight years old. They tried the obvious but Michael had never lived in a cage. As a precursor to lovemaking, chasing an angry cockatoo flying from room to room was a disaster. Charlotte’s claustrophobia eliminated shut windows and doors. Finally, after weeks of shattered crescendos, her husband had had enough. When Michael attacked he pivoted back onto his knees, snatched him up with both hands, and threw him into the garden. An hour later, peering through the bedroom window, Michael was ruffled and noticeably depressed, although not as depressed as Charlotte, who faced the dilemma of loving a man who throws sulphur-crested cockatoos.

When she came in with Michael early the next morning she was pale with contained rage. “I have to see Dr Joe.”

“He’s with a patient,” I said, “but I could …”

“I’m sorry, but I need to see Joe straight away,” she said, while Michael stared at me from her left shoulder with a single obsidian eye. “If I don’t, I’ll be forced to do something terrible. I’m serious, Tim.”

This is significant. A meaningful engagement with the power of oestrogen is a vital part of veterinary practice. It’s wives, mothers and girlfriends who initiate most of the pet care in Elizabeth Bay. Even when the surgery is flaming with rainbows, a clear understanding of oestrogen is very useful. We both get on well with our clients, but Joe has the edge.

Women with pets love Joe, there’s no more honest way to put it. He has a presence that I’ve never been able to classify. There are plenty of words: empathy, humour, intelligence, but none really do the job when it comes to understanding Joe’s relationships with our female clients. It’s not as if he’s stunningly prepossessing. For as long as I’ve known him, he’s referred to the anatomy supporting his glasses as his snout, for good reason. When his magnified marsupial eyes blink behind heavy spectacles it’s like window blinds snapping up and down. He’s very healthy, that I’ll say for him. Twenty years of amateur boxing have given him a muscular welterweight frame, a good match for his emphatic nature.

He’s most comfortable with women, but Joe is no ladies’ man. His obsession with ethics prevents him manipulating for pleasure, although much of his charm does lie in his unusual view of devotion. “Love has been in the chemistry of the cosmos since the beginning of time,” he said once when we were studying animal attachment at university.

“Actual love?” I remember asking, naturally dubious.

“It’s a biochemical algorithm created in a supernova.”

“What kind of biochemical algorithm?”

“A mix of lipids and alkaloids, electrical energy, magnetism – the stuff you should’ve learned in high school.”

Over the years I’ve become used to such pronouncements, usually based on his fascination with obscure papers on astrochemistry. Joe is a walking TED Talk in that way – often mystifying, but sincere.

When I took Charlotte into his surgery with a bewildered parrot clinging to her arm, Joe was managing the difficult birth of a white mouse doe’s first brood. Michael Hutchence was in such bad shape he turned gloomily aside from the wriggling pink titbits on the examination table and buried his head in his loved one’s armpit.

“Oh hello,” said Joe, with a quick glance. “Michael causing trouble, is he?”

“It’s pathological, Joe, I can’t take it anymore.”

“He loves you, Charlotte, he doesn’t know what else to do.”

“That’s your solution?”

Joe stopped what he was doing and began the pastoral care that makes him so good at his job. Charlotte was struggling, I think, embarrassed by the threat of breaking down, and Joe filled the space between them with an easy compassion. Without being invasive, he seemed to connect to a vulnerable part of Charlotte she was reluctant to reveal. Radiating kindness, he handed me his box of surgical gloves. “Tim, do us a favour and take over the delivery. So far the young mum’s doing okay. Charlotte and Michael, come with me.”

They went into his office to consult while I kept an eye on the doe to stop her killing her pups, something that mice often do if they’re disturbed during birth.

After half an hour Charlotte left without Michael. On her way out she wrapped her arms around Joe in an intense hug. It was obvious she was deeply relieved.

“What did you say to her?” I asked, when he’d shown her out of the clinic.

“A lot of things, but in the end we talked about astrochemistry.”

“Astrochemistry?”

“Actually, astrochemistry and love.”

“Not your rant about the cosmos? She’s medically trained, Joe, she’ll think you’re a lunatic.”

“Not at all, she liked the science. I just said everything living is connected by a biochemical algorithm, including women and parrots, and a vital part of that biochemical algorithm is unstoppable attraction created by sentient genetics.”

“In other words, aside from ruining Michael’s life by locking him in a cage, there’s not a lot we can do.”

“Well, no.”

Eventually, Joe convinced Charlotte to farm Michael out to her uncle Ralph, a retired show boy from the cruise ship circuit; but the real outcome for Charlotte was a reinvigorated marriage. Judging by what I witnessed in the surgery that day, Charlotte’s vulnerability had turned to relief then, I hope, happiness.

Which brings me to the true point of my parrot story. Joe Franken’s record of loving animals is brilliant. His relationship with our female customers is unique. But his history with women outside the clinic is a mess. He genuinely believes love is a fundamental part of the universe, but what begins in a shower of stardust often collapses in six months or a year with a sad phut. Even though the end is rarely sordid, it’s always demoralising, and Joe retreats back into his work for months on end.

For as long as Joe and I have been friends, we’ve been anxious to find “The One”. Now that we’re both in our late thirties, this inclination has morphed into a desire to start families but, with the exception of myself, I’ve never known anyone so hopeless at making love last as Joe Franken. Neither of us is predatory by nature, nor are we misogynists. We’re just a couple of vets searching for the certainty of shared devotion.