Читать книгу Fallen Angel - Andrew Taylor, Andrew Taylor - Страница 16

7

Оглавление‘… we are somewhat more than our selves in our sleeps, and the slumber of the body seems to be but the waking of the soul.’

Religio Medici, II, 11

Sally had not expected to sleep on Saturday night, the second since Lucy’s disappearance. Part of her was determined to stay awake in case Lucy needed her. When David Byfield rang with the news that Michael was safe, however, tiredness dropped over her like a blanket.

Judith, the policewoman who had been on duty on Friday, and who had relieved Yvonne in the early evening, took advantage of this weakness. She persuaded Sally to go to bed, brought her a cup of cocoa and cajoled her into taking another sleeping tablet.

‘It’ll just send you to sleep,’ Judith said, her Welsh voice rising and falling like a boat on a gentle swell. ‘It’s not one of these long-term ones that knock you out for ages. There’s no point in you flogging yourself to keep awake.’

‘But what if – ?’

‘If there’s any news, I promise I’ll fetch you straightaway.’

Sally took the tablet and drank her cocoa. Judith lingered for a moment, her eyes moving round the room.

‘Do you want something to read? A magazine?’

‘Could you pass me the books over there? The ones on the chest of drawers.’

Judith brought them to her. ‘I’ll look in a little later. See how you’re doing.’

Sally nodded. The door closed behind Judith and she was at last alone. Lucy. Her eyes smarted with tears. She wanted to bang her head against the wall and scream and scream.

Miss Oliphant’s books lay before her on the duvet: unfinished business that would normally have nagged Sally until she had dealt with it. She touched their covers one by one with the fingertips of her right hand. The Bible. The Prayer Book. The Religio Medici. The first two were bound in worn black leather, dry with age, their spines cracking and in places breaking away from the covers. Sally knew without looking that the paper would be so thin that it was almost invisible, and that the type would be so small that even someone with 20:20 vision would have an effort to read it. The Religio Medici had a larger typeface but the book was as battered as the others. All three smelled musty: tired, repulsive and unwashed. Sally shivered, reluctant to open any of them. Each book might be a miniature Pandora’s Box full of unexpected evils.

‘You mustn’t blame yourself,’ David Byfield had told her on the telephone.

‘Then who else do you suggest? God?’

There was a silence at the other end. Then David said dryly, ‘The person who took Lucy, perhaps.’ He had overridden her attempt to interrupt. ‘Concentrate on this: you mustn’t worry about Michael. He’ll sleep it off tonight and be with you tomorrow. You mustn’t blame him, either, or yourself. Do you understand, Sally? It’s most important. Nor must you stop hoping and praying.’

‘I can’t pray.’

‘Of course you can.’

‘Listen,’ Sally began, ‘I don’t like –’

‘Don’t argue. Pray, go to bed and try to sleep. That is the best thing you can do.’

David Byfield’s voice had sounded unexpectedly youthful over the phone. Like Derek Cutter, the old man had been in full pastoral mode, but his technique differed completely from Derek’s: the former’s had made her squirm; David’s infuriated her. Talk about arrogant, Sally thought. What did he know about losing a child? The autocratic, patronizing bastard: who had given him the right to give her orders? She glowed with anger at the memory. Only then did it occur to her that David might have intended to achieve just that effect. He was a clever man, she conceded: an old fool, but still clever.

Her eyelids drooped, she slid down the bed. Endowed with a life of their own, her fingertips continued to stroke the binding of the three books. Audrey Oliphant, she thought sleepily: that’s a strange name. Oliphant sounded like elephant. Had there once been a saint called Audrey? Then, as sudden and as violent as a flash of lightning, the knowledge that Lucy was not there slashed across Sally’s mind. She sat up in bed and screamed. But the sound which came out of her mouth was no more than a whimper. She sank back against the pillows.

The movement had dislodged the books. The corner of a piece of card protruded from the Religio Medici. Sally pulled it out. It was a postcard of the west front of a great church, an old-fashioned colour photograph bleached with age. The building was familiar, but for the moment her mind refused to produce the name. She flipped the card over: Rosington Cathedral. There was writing, too. She squinted at the postmark. April 1963? 1968? It was addressed to ‘Miss A. Oliphant, Tudor Cottage, The Green, Roth, Middlesex’. The name Roth was faintly familiar. Somewhere west of London? Near Heathrow Airport? She tried to decipher the message.

Too many tourists and more like Feb. than April but choral evensong was super. Our mutual friend still remembered. Small world! See you on Tuesday. Love, Amy.

A glimpse of other lives, Sally thought, of a time when Audrey Oliphant had perhaps been happy. Why do we even bother to try?

The card slipped from Sally’s hand, and she sank into sleep. Thanks to the tablets she lay there for what she afterwards discovered was almost seven hours. For much of the time she moved restlessly through the dark phantasmagoria of her dreams, searching for Lucy. This must be hell. When she awoke, she swam up from a great depth, painfully conscious of changing pressure and a desperate need to reach the surface.

Lucy.

Still with her eyes closed, she made an enormous effort and gathered together the pain, the fear and the anger. She made a ball of it in her mind and kneaded it like dough. The ball was streaked with colours: red, brown, green and black, the colours of the emotions. She picked it up and threw it over her shoulder. Then she found the strength to open her eyes.

The bedroom was in darkness, apart from a band of light from the streetlamp slipping between the curtains and the red digits glowing on the clock display. Her pulse was racing, her mouth was dry and her eyelids were swollen and sore.

No Lucy, she thought, and no news of her either: they would have woken me.

Something had driven her awake. She had fled to consciousness as if to a refuge. Had something down there been even worse than this waking knowledge of Lucy’s absence?

It was six-fifteen. She switched on the bedside light. Judith must have come in to turn it off last night. Miss Oliphant’s books were in a neat pile on the bedside table. Sally lay back on the pillows, fighting the despair that threatened to overwhelm her. She tried to pray: it was no use – the lines were down, the airwaves jammed, or perhaps no one was bothering to answer at the other end. Pray, David Byfield had told her; pray and hope. She could do neither.

Gradually, fragments of her dreams slipped into her conscious mind. She glimpsed Miss Oliphant, attired in episcopal robes, standing in front of the high altar of a great church, which Sally knew must be Rosington Cathedral. Miss Oliphant was reading the Service of Commination from the office for Ash Wednesday in the Book of Common Prayer. Is that why they’ve taken Lucy, because we were cursed? But there are no woman bishops, Sally remembered thinking in her dream, not in this country. Have they changed the rules and not told me? In the dream world this possibility had been far more unsettling than the sight of Miss Oliphant, last seen dead in a hospital bed, apparently alive and well.

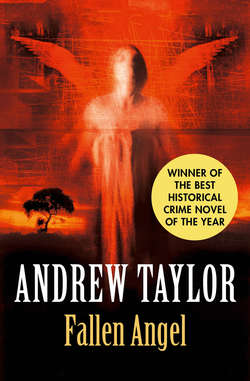

Another fragment of another dream had concerned David Byfield. He had seen an angel flying low over Magdalene Bridge in Cambridge.

‘Real feathers,’ he insisted to Sally and Michael, ‘rather like a buzzard’s.’

‘But Lucy’s missing!’ Sally shouted.

‘This is far more important.’

In a different part of the same dream, she and Uncle David were in a police station that smelled like a public lavatory. Chief Inspector Maxham leaned across the counter towards them, sucking in his breath, the air hissing between his tongue and his teeth.

‘Couldn’t have been an angel, sir. Angels don’t exist.’ Sally was embarrassed. Grown men did not believe in angels. David became very angry with Maxham.

‘Don’t be naive, Officer. You’re not competent to make wild assertions like that.’

The chief inspector smiled, revealing Yvonne’s perfect teeth. ‘You were dreaming.’

‘I was not.’

Uncle David raised his arms and spread them wide. To her horror, Sally saw that his dark clerical suit was sprouting two rows of silvery-white feathers, one for each arm, running down the sleeves from shoulder to cuff. Uncle David was growing wings.

By eight o’clock, Sally had showered, dressed and had breakfast, which in her case consisted of three cups of coffee. She and Judith sat at the table in the living room. Judith tried to entice Sally’s appetite from its hiding place by filling the flat with the smell of toasting bread and boiling herself an egg.

‘No news is good news.’ Judith’s face creased with anxiety, and Sally felt guilty for spurning all those good intentions. ‘Why don’t you have a spoonful of cereal – something light like cornflakes?’

Sally reached for the coffee pot. ‘Perhaps I’ll have something later.’

‘I expect you’ll want to go to church this morning. I’m sure Yvonne will drive you.’

Bugger church. ‘I don’t want to, thanks.’ Sally glimpsed, or imagined, hurt surprise in Judith’s eyes. Bugger Judith. But it wasn’t that easy to slough off the habit of being considerate. She heard herself saying soothingly, as if Judith, not herself, were the victim: ‘It’s kind of you to think of it, but I want to be here when my husband comes home.’ With his slippers warming by the fire, the newspaper on the arm of his chair and fresh tea in the pot? ‘And of course there might be some news.’

‘I do understand.’ Some of Judith’s creases vanished. ‘Won’t be long now, will it? It will be easier with the two of you.’

Sally nodded and sipped her coffee. She doubted if it would be easier when Michael came. Nothing could be easy without Lucy. In the second place, there wouldn’t be just the two of them because David Byfield was coming up to London, too. In the third place, Michael, much as she loved him, was likely to create more problems than he solved. He habitually repressed his emotions, which meant when they did come to the surface they tended to be under great pressure and boiling hot.

‘I wonder if the newspaper’s come,’ Sally said, her eyes meeting Judith’s.

‘I’ll see, shall I?’

Before Sally could protest, Judith was on her feet and moving towards the door. A moment later she returned with the Observer.

‘Would you like me to …?’

Sally held out her hand for the newspaper. ‘I’d rather find out myself.’

The story was confined to a few paragraphs on one of the inside pages. Lucy Appleyard, four, had disappeared from her child minder’s; the police had not ruled out the possibility of foul play. Chief Inspector Maxham provided a guarded comment, which in effect said no more than that the police were investigating.

‘The whole parish is praying for Lucy, Sally and Michael,’ Derek Cutter had told the Observer‘s reporter. ‘Sally’s a marvellous curate. She’s already made her mark at St George’s.’

Sally pushed the newspaper, open at the story, across the table. Judith read it quickly.

‘Fair enough, I suppose,’ she said brightly.

‘I wonder what the tabloids are saying.’ Sally winced. ‘Perhaps it’s better not to know.’

A key scraped in the lock of the door to the landing.

‘That’ll be Yvonne.’ Judith gathered up her handbag, and risked a small joke. ‘Just in time for the washing-up.’

The living-room door opened and Maxham came in. Yvonne’s blonde head bobbed above his shoulder in the hallway behind him. Judith glanced at Sally and stiffened, ready to take action. Sally put her hand to her mouth and stared at Maxham.

‘There’s been a development, Mrs Appleyard.’ Air hissed into his mouth. ‘It may not be connected with Lucy, so don’t get upset.’

Maxham came to a halt a few paces inside the room. Yvonne moved round Maxham and came to stand beside Sally. Judith edged closer. My God, what are they? Wardresses?

‘Do you know a church called St Michael’s?’ he asked.

‘Which one?’ she snapped. ‘There must be dozens.’

‘In Beauclerk Place – west of Tottenham Court Road, near Charlotte Street.’

She shook her head, unable to speak.

‘When the caretaker – churchwarden, would it be? – came to unlock this morning, he found a black bin-liner in the porch. I gather there are wrought-iron gates on the outer arch of the porch and a proper door inside. Someone must have slipped the bin-liner through the railings or maybe over the top.’

Get on with it. Sally watched Maxham’s face, saw the pale eyes blinking behind the black-rimmed glasses and the muscles twitching at the corners of the mouth. With a shock she realized that he was stalling because he found this no easier to say than she did to hear.

Air hissed. ‘The fact of the matter is, Mrs Appleyard, there were some clothes inside that bag. A pair of child’s tights and a pair of boots. They seem to resemble the ones you described Lucy as wearing.’

‘For Christ’s sake – what about Lucy? Is she there, too?’

Maxham hesitated, greedily sucking in breath. ‘Well,’ he said slowly. ‘Yes and no.’

St Michael’s, Beauclerk Place, stood at the end of a cul-de-sac squeezed between higher, younger buildings to either side and behind it. It was a scruffy little building built of red brick, rectangular in design, with pinnacles at the corners and debased perpendicular windows. The visible windows were protected with iron grilles and decades of grime. The church was like a child who has never had quite enough love or money devoted to it.

The uniformed policeman pulled aside the barrier to allow Maxham’s unmarked Rover to drive into the cul-de-sac. The buildings on either side were post-war, with plate-glass windows and Venetian blinds: probably offices, empty on a Sunday. As yet, there were no sightseers, but the police were ready. The car slid to a halt near the church. Two police cars were parked nearby.

The porch had been tacked on to the south-west corner of the church. The police had screened off the entrance. On the left of the porch was a row of iron railings which ended in a matching gate.

Sergeant Carlow switched off the engine. He looked over his shoulder at Maxham, sitting in the back of the car with Sally. Maxham nodded. Carlow extracted his long body from the car and walked towards the screened-off porch. His hips were unusually wide for a man’s, Sally registered automatically, and as he walked his bottom swayed like a woman’s.

Maxham folded his hands in his lap. ‘Just going to see what’s what.’

For a few seconds, silence spread through the car. In the front passenger seat Yvonne stared fixedly through the windscreen. The inspector rubbed his fingers on his thigh. Carlow reappeared. He looked paler than ever.

Maxham turned his head towards Sally. ‘You sure you’re up to it? Still time to change your mind.’

‘I’m quite sure.’

‘We can wait till your husband –’

‘No.’ My baby. ‘Can we get it over with?’

Maxham nodded. The three of them got out of the car. It was suddenly cold: the wind funnelled through the cul-de-sac and escaped into the dull, grey sky. Sally forced herself to look away from the porch. She noticed that the gap between the railings and the church had silted up with a thick mulch of empty lager cans and fast-food wrappings, and that the gate at the north-west corner guarded the entrance to a narrow alleyway between the north side of the church and the adjacent building.

According to a notice on the wall, the Anglicans now shared St Michael’s with a Russian Orthodox congregation and a Methodist one. Otherwise it would probably have been made redundant long ago. Perhaps that would have been better than this unloved half-life.

Half a life, half a person?

Sally found herself staring at the porch. From what she could see above the screens, it was about six feet wide and nine feet deep; it was covered with a pitched roof of cracked pantiles streaked with lichen and moss.

Maxham put a hand under Sally’s elbow. They walked towards the screen. Yvonne and Sergeant Carlow fell in behind. A one-legged pigeon with frayed feathers hopped across their path. An amputee. To those in fear, creation was nothing but a mass of portents. Sally pulled away from Maxham and thrust her hands deep into the pockets of her long navy-blue coat. They rounded the corner of the screen.

The light dazzled her. For a moment she stopped to blink and stare. Two floodlights gave the interior of the porch a hallucinogenic clarity. The outer gates were open. On either side were benches, with notice boards above. It should have been sheltered in there, but the notices fluttered and rustled in the wind. A photographer was shooting away seemingly at random, the shutter falling in a stammering rhythm like irregular rifle fire.

The little space was crowded. Beside the photographer, another scene-of-the-crime officer was dictating into a hand-held machine. A third was measuring the dimensions of the porch. A fourth man, with a bag next to him, was kneeling in the far left-hand corner. Sally glimpsed shiny black plastic.

‘This is Dr Ferguson,’ Maxham said. ‘Mrs Appleyard.’

The kneeling man half-turned and nodded, acknowledging the introduction.

Sally swallowed. ‘Where –?’

‘Here, Mrs Appleyard.’ The doctor rose to his feet in one supple movement. He was younger than Sally, fresh-faced, with a healthy tan and a Liverpool accent. His eyes slid to Maxham, then back to Sally. ‘Are you sure you want to see this?’

‘Yes.’ With an effort she kept her voice low, concealing the scream inside her head.

Ferguson nodded. ‘Over here.’

He gestured not as Sally had expected towards the black plastic on the floor behind him, but to a plastic sheet on the bench on the left. Two L-shaped ridges showed underneath in relief, each about twenty inches long. Automatically Sally looked up, unable to keep her eyes on the two ridges. She examined the notice immediately above, noted with furious concentration the yellowing paper, the nearly illegible typed letters and the circular rust stains left by vanished drawing pins.

She was aware that Maxham and Yvonne had moved a step nearer and were now standing directly behind her. The other police officers had stopped what they had been doing. The doctor was watching her, too. All of them were in position, she realized, ready to catch her when she fainted. Ironically, the thought braced her.

‘You’re ready?’

Ferguson drew back the plastic sheet. Beneath was a transparent plastic bag with a neatly written tag. The bag contained a pair of small, white, woollen tights with ribbing on the legs. For an instant they looked as if they had been stuffed with kapok like cuddly toys. The tights were lying in a reddish-brown puddle of blood. Sally compressed her lips and swallowed. She thought of meat from a supermarket defrosting on its plastic tray. Blood need only be blood: nothing more, nothing less: largely composed of water, a means of supplying living tissues with nutrients and oxygen and of removing waste products. Once separated from the pumping heart, it was nothing but a reddish-brown liquid.

Drink ye all of this; for this is my blood.

‘Mrs Appleyard?’ Ferguson murmured. ‘Steady, now.’

‘I’m fine.’

The waist of the tights lay flat against the plastic. There was no kapok in there. The blood was thickest from the top of the thighs to the waist of the tights. You could no longer see the whiteness of the wool.

O Lamb of God –

Sally’s eyes travelled down the length of the legs to the feet. The feet were wearing miniature red cowboy boots. They were dainty things, the leather supple, a delicate pattern stitched in black thread at the ankles. In the toe of the nearer one was a shallow cut about half an inch in length.

You naughty girl. Have you any idea how much those cost?

‘The ankle boots are Italian.’ As Sally paused, she heard a faint, collective sigh behind her. ‘They’re made by someone with a name like Rassi. I bought them at a shop in Covent Garden about two months ago.’ The boots had been an extravagance that Sally had been unable to resist. She had put towards the cost the money that David Byfield had sent for Lucy’s last birthday. Michael had been furious. ‘I wrote Lucy’s name on the back of the maker’s label.’ Not the sort of boots you could afford to lose, she had thought. ‘As for the tights, I’m pretty sure she was wearing ones like that on Friday. It’s hard to be absolutely certain because of the blood.’

Lucy’s blood. Oh Christ – can’t you stop this?

They had known what Lucy was wearing, down to the maker’s name in the boots. But they needed to be sure. Sure? Gingerly, Sally stretched out her hand towards the two legs.

‘Mrs Appleyard –’ the doctor began.

Sally ignored him. She touched the leg very gently with the tip of the index finger of her right hand. ‘It’s icy.’

‘It may have been deep-frozen until recently.’ Maxham’s voice was harsher than usual.

‘Like the hand they found in Kilburn Cemetery?’

‘Yes.’

What struck Sally now was the silence. Here they were in one of the world’s great cities, in the middle of a pool of silence. There must have been at least a dozen police officers within thirty yards and they all seemed to be holding their breath.

Dear God, the pain. Had they had the decency to kill her first, and kill her swiftly?

Sally ran her fingertip delicately down the leg, following the curve of the knee, on down the shin to the top of the boot. She bowed her head.

‘Mrs Appleyard?’ Maxham sounded anxious, with just a hint of exasperation. ‘That’s all we need, thank you. You’ve been very helpful. Very brave.’

Sally slipped the thumb and forefinger of her hand right round the ankle and squeezed it, through the plastic bag and the leather. She felt the hardness of the bone underneath.

‘Mrs Appleyard,’ said Ferguson, ‘there’s a possibility of postmortem damage. That could give us problems at the autopsy.’

Yvonne put her hand on Sally’s arm. Sally shook her off. Someone snarled like a dog deprived of a bone. Me. Puzzled, she ran her hand round the bend of the L and on to the foot itself. Maxham grabbed her other arm. She felt the toes. It wasn’t possible. Yvonne and Maxham pulled her gently back.

‘I’m sorry, Mrs Appleyard.’ Maxham allowed his exasperation to show plainly. ‘Now we’ll get you home. Your husband will be back soon.’

I don’t want my husband: I want Lucy.

Then Sally saw how the impossible might have happened. Must have happened.

‘The legs are too long,’ she said slowly. ‘So they aren’t Lucy’s.’

Maxham allowed Sally to sit inside the church because he could not think of a valid reason to prevent her. Besides, she knew, he had assumed that she wanted to pray, a possibility which embarrassed him. His embarrassment was a weapon she could use against him.

It was very cold. The gratings set into the cheap red tiles suggested underfloor heating, but either the system didn’t work or the people using the church could not afford to run it. The silence pressed down on her. The air smelt faintly of incense. The brass of the lectern was smudged and dull. She glanced up at the roof, plain pitch pine, full of darkness, shadows and spiders’ webs.

Her eyes drifted along the line of the roof to the east wall. A large picture in a gilt frame hung above the altar. The light was poor and the paint was dingy. Maybe the Last Judgement, Sally thought, a cheap and nasty Victorian copy if the rest of the church was anything to go by. Christ in Glory in the centre of the picture, a river of fire spewing forth at his feet; flanked by angels and apostles; and below them the souls of the righteous queuing for admission to paradise; and the archangel with the scales – Michael or Gabriel? – weighing the souls of the risen dead. A picture story for children afraid of the dark.

And Lucy? Was she afraid? Or already dead?

Sally let out her breath in a long, ragged sigh. Don’t think about that. Think about the good news. The legs were not Lucy’s, any more than the hand had been. They were the wrong shape, wrong size, wrong everything. Lucy’s were thinner and less muscular, and her feet were much smaller than the feet which had been stuffed into Lucy’s red Italian cowboy boots.

At first Maxham had not believed Sally. Even Yvonne and Dr Ferguson had been sceptical. They had all been suspicious of her certainty, willing to attribute it to wishful thinking.

I’m her mother, damn you. Of course I know.

Sally bowed her head. Once again she tried to pray, to thank God that the legs were not Lucy’s, and that therefore Lucy might still be alive. But her mind swerved away from prayer like a horse refusing a jump. An invisible barrier hemmed her in, enclosing her in her private misery. It was as if the church itself had surrounded her with a wall of glass which cut off the lines of communication. For an instant she thought she glimpsed the building’s personality: sour, malevolent, unhappy – a bricks-and-mortar equivalent of Audrey Oliphant, the woman who had cursed her.

What’s happening to me? Churches don’t have personalities.

Gratitude was in any case misplaced. The legs had belonged to another child. Should she thank God for the other child’s death and mutilation? Beside that terrible fact, the goodness of God receded to invisibility.

Sally opened her eyes, desperate to find a distraction. On the wall nearest to her hung a board with the names of the incumbents inscribed in flaking gold letters, beginning with a Reverend Francis Youlgreave MA in 1891 and ending, seven names later, with the Reverend George Bagnall, who had left the parish in 1970. It was a big board and three-quarters of it was blank. No doubt Youlgreave and his immediate successors had imagined that the list of incumbents would stretch on and on, and that the building would always be a place of worship.

Things could never get better, she thought bitterly, only worse. How those long-gone priests would have hated the thought of her, a woman in orders. And what was the purpose of it anyway? It now seemed absurd that she had fought so hard to be ordained, and that she should devote her life to playing a minor part in the affairs of a dying cult. So far the effect had been wholly evil: she had ruined her own life, damaged Michael’s and abandoned Lucy. She was to blame. She was too angry with herself even to share the blame with God. Oh yes, he was still there. But he didn’t matter any more. If the truth were told, he never had. He didn’t care.

You mustn’t blame yourself. David Byfield’s words twisted in her memory and took on a bitter and no doubt intended irony. He blamed her. He always had blamed her, the woman who had committed the double sin of wanting to be a priest and taking away his Michael. She wondered yet again what bound the two men so tightly together. Whatever the reason, now she had her reward for breaking into their charmed relationship, and no doubt David was rejoicing.

Sally stared at the list of priests. The church’s dedication was written in gothic capitals at the head of the board: ST MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS. Her mind filled with a thrumming sound, as though a thousand birds had risen into the air and were flying across the mud flats of an estuary. Her husband’s name was Michael, and the church was dedicated to Michael. Just a coincidence, surely. It was a common name. Only a paranoiac would think otherwise.

And yet –

This evil was beginning to take shape. It had been planned and executed over a long period. The brown-skinned hand in Kilburn Cemetery and the bleeding legs in the porch must be connected with each other because there were so many correspondences: both had been deep-frozen; both were parts of a child’s anatomy; both had been left in places which were sacred; and they had been found within twenty-four hours of each other. It was theoretically possible that the two were separate incidents – that the story of the severed hand had inspired a copycat crime – but this seemed less likely. The boots and the tights left no doubt at all that Lucy was at the mercy of the same person. Had there been a message there?

Lucy’s dismembered, too.

Whoever had taken her had not done so merely for sexual gratification or from emotional inadequacy; or if he had, that was only a part of it. What lay in the porch had been designed to shock. And the urge to shock had been so great that it had outweighed the risk of being seen.

The wings rustled and whirred. Not just to shock: also to tease.

Had Lucy been chosen not for herself but because she was a policeman’s child? Sally remembered Frank Howell’s feature on St George’s in the Evening Standard. Perhaps someone had read it who had a grudge against the police in general or Michael in particular.

Then why not leave the remains outside a police station? Why the church today and the cemetery yesterday? Perhaps the hatred was aimed at God rather than the police. A further possibility struck her: that this might be a more extreme form of the loathing which had gripped Audrey Oliphant; and in that case it followed that Sally herself, by wanting to become a priest, could have been directly responsible for bringing down on Lucy’s head the attention of whoever had taken her.

‘I’m getting paranoid,’ she told herself, her voice thin and childlike in the empty spaces of the cold church; she shocked herself, for she had not realized that she had spoken aloud. ‘Stop it, stop it.’

The thoughts spurted through her mind – fragmented and disjointed. The noise of the wings grew louder until it obliterated all other sounds and swamped her ability to think. The thrumming was so loud that Sally hardly felt like Sally: she was merely the sound of the wings. She drowned in the sound, as if in the black mud of the estuary.

‘No. No. Leave me alone.’

The thrumming grew even louder. It was dark. She could no longer breathe. She heard a great crack, so loud that for a moment it dominated the thrumming of the wings. Cold air swirled around her.

‘That’s quite enough.’ The voice was furious and male. ‘This must stop at once.’

Sally opened her eyes and turned her head. Through her tears she saw Michael’s godfather, David Byfield, stalking down the aisle towards her.