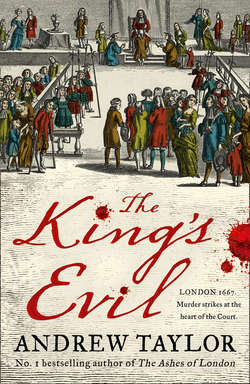

Читать книгу The King’s Evil - Andrew Taylor, Andrew Taylor - Страница 23

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

ОглавлениеTOWARDS THE END of her second day at Mangot’s Farm, Cat sat by the window of her chamber, looking out over the sloping fields behind the house. The light was fading, and the tents and cabins below were mercifully less obvious than they were in the daylight.

It was a chilly evening. No more than two or three fires were burning, though scores of people were living there, for firewood was scarce after all these months. It was quieter than it had been earlier in the day when, under Israel Halmore’s direction, the men of the camp had been building further shelters and strengthening the existing ones, using the nails and canvas that he and Mangot had brought from London. There had been ground frosts already, and the refugees realized that winter would soon be upon them.

Cat’s casement was open, and she heard the sound of singing from one side of the camp; some of the men gathered here in the evening and drank a raw grain spirit that they distilled in one of the ruined outhouses in the farmyard. The smell of smoke drifted towards her, mingling with the smells from the stream the refugees used for a latrine. Once upon a time, Mangot’s Farm had prospered, but that time was long gone.

This refugee camp was not like those that the authorities had established on the outskirts of London in the immediate aftermath of the Great Fire, such as Moorfields and Smithfield. These, almost all closed now, had been relatively well-administered affairs with makeshift streets neatly laid out and lined with temporary shops, and with access to markets and to the jobs that had sprung up as the city began to grow anew from its own ashes. This camp, by contrast, was small, isolated and chaotic. The only authorities its inhabitants recognized were Israel Halmore, who dominated the others by force of personality, and Mr Mangot, who let them use his land because he could no longer work it himself, and because he believed that God had commanded him in a vision to expiate his sins and those of his dead son by providing a home for the homeless.

It was warmer in the kitchen, but she preferred to be up here, alone in the little chamber under the eaves that had once belonged to the old man’s son. The door was solid, and she could bolt herself in. Besides, there was nothing to attract her in the rest of the house, which was gradually turning into a ruin, and only a fool would venture into the camp itself unless they had no choice in the matter.

She felt sleepy, and her mind drifted back to the commission at Clarendon House. Modernizing an old building like the pavilion was a tricky matter, as Mr Hakesby had pointed out to my lord; it would have been far simpler to pull it down altogether and rebuild it from scratch to match its near twin in the opposite corner of the garden. However well they did it, the result must be a mongrel building, particularly from the rear and side elevations, neither one thing nor the other. On the other hand, she thought, the mansion itself was a mongrel building, for all the money that had been spent on it. It was classical in its pediment and its symmetries but, in the native English manner, it lacked classical orders. Should they ever look down on it from heaven, Andrea Palladio would shake his head and Vitruvius would throw up his hands in disgust.

The pavilion was a matter of sentiment, Cat had understood, a gift from an old man to his ailing wife. At the start, they had occasionally seen her ladyship herself. Later, when her health worsened, Lord Clarendon, wincing at the pain from his gout, had sometimes shuffled down the garden on the arm of Mr Milcote to inspect the works. But then Lady Clarendon had died, and he had come no more. Mr Milcote, my lord’s gentleman, came in their place.

Cat’s mind shied away from Mr Milcote. She was increasingly worried by the conversation she had overheard in the cart yesterday morning, on their way to the farm. If Halmore had been right, the Duke of Buckingham was orchestrating the attacks on Clarendon House. Who was the Bishop, who was acting as the Duke’s agent? It had sounded as if he planned something else to harm Clarendon, something much worse. Perhaps he would incite the mob to break down the gates and set fire to the house itself. He might even attack Clarendon in person.

She had liked Lady Clarendon, and she respected the Earl; good clients, who took an informed interest in the work and paid Hakesby’s bills on time, were few and far between. The house itself might not be architecturally perfect, but she had no wish to see it damaged. She wished there were a way to warn them.

A woman screeched somewhere in the camp, reminding Cat that she could not stay here for ever – it was time for her to prepare the old man’s supper, if one could call the meal that. This was part of the price she paid for his hospitality.

She went slowly down the creaking stairs, avoiding the third tread from the bottom, which was rotten, and went into the kitchen. Mr Mangot was already there. He was reading his Bible by the faint, evil-smelling glow of a rushlight, running his finger slowly along the lines of words. He still wore his smock, which was made of unbleached linen and too large for him. He was painfully thin and always melancholy.

Cat made up the fire and set the pan of soup to warm. There seemed to be nothing else to eat here, apart from stale bread which they dipped in the soup to soften it. She had given Mr Mangot another five shillings this morning in the hope that he would buy more food.

Outside in the yard, one of the dogs barked. The other dog took it up. Then they fell silent.

‘Is someone coming here?’ she whispered, slipping her hand into her pocket, where the knife was.

‘The carrier, probably,’ he said, without looking up. His voice sounded creaky with disuse. ‘They bark differently if it’s a stranger. He’ll see Israel first, then he’ll come here. He calls for orders on Monday evenings. He’s a pedlar, too – always got something to sell.’

‘Food?’ Cat asked.

He shook his head, his finger still moving across the page.

‘Could he take a letter to London for me?’

Mangot raised his head from the book. His eyes were so filmy that she wondered he could read at all. ‘A letter? You can ask him. Who’s it to?’

‘Your nephew.’

He snorted. ‘Are you his sweetheart?’

‘No.’

‘Just as well.’

She glanced at the pot on the smouldering fire. The soup would take another quarter of an hour to heat through, at least. ‘I won’t be long.’

She took a rushlight upstairs to her chamber and wrote a few lines to Brennan.

Beg H to warn Ld C that the D of B bribes the mob outside CH, through a man they call the Bishop, who is their leader. The Bishop intends some future move against him that will cause C particular pain. H could write a letter, saying he’d heard tavern talk about it.

She left the note unsigned. She folded the paper, torn from her notebook, and wrote Brennan’s name on the outside. She had nothing to seal the paper with. She wondered if it would do any good, even if it reached Brennan: he would have to persuade Hakesby to take it seriously – no easy task – and Hakesby would have to warn Lord Clarendon. It might be better if he went instead to Mr Milcote. She hesitated, wondering whether to unfold the letter and add a postscript. Then she frowned. There was unfinished business with Milcote; wiser not to involve him.

There was a hammering on the door downstairs. She put the letter in her pocket and went down to the kitchen. The carrier was showing Mangot a packet of newly printed chapbooks, sermons and pamphlets. He looked up as she entered, revealing a wall eye, and appraised her swiftly, before turning back to the farmer.

While the men were talking, she wiped the table and set out the wooden platters and cups. She stirred the soup, willing it to heat up more quickly. Mangot bought a pamphlet about a Papist plot to murder the King with a poisoned dagger as he was going to his devotions in Whitehall.

When the carrier was packing up his stock, Cat asked him if he would take a letter to London for her. He agreed to deliver it to Henrietta Street in the morning. He charged her two shillings for the service, which they both knew was an extortionate price.

‘I want you to put it in the hands of a particular man, not a servant or anyone,’ she said. ‘He works for Mr Hakesby, at the sign of the Rose, and his name’s Brennan, and he has a thin face and ginger hair. He’s Mr Mangot’s nephew.’

The carrier smiled at her, revealing a toothless mouth, and spat into the fire, narrowly missing the pot with the soup. ‘Then that’ll be an extra shilling.’

She paid him reluctantly. As the carrier turned to go, the back door opened. A current of cold air swept into the kitchen, followed by the tall figure of Israel Halmore.

A rabbit dangled from his right hand. It was already skinned and gutted. He tossed it on to the table, where it lay, lolling, in a parody of ease. ‘For the pot, master.’