Читать книгу The Ashes of London - Andrew Taylor, Andrew Taylor - Страница 9

Author’s Note

ОглавлениеOn 1 September 1666, London was the third largest city in the European world, after Paris and Constantinople. Estimates vary but its population probably amounted to around 300–400,000 people.

The city had three great centres of political power, strung along the north bank of the Thames – just as they are today. The wealth of the merchant classes was concentrated in the walled medieval City between the Tower in the east and St Paul’s Cathedral in the west. A mile further upstream, beyond Charing Cross, was the sprawling Tudor and Stuart palace of Whitehall; this was the King’s principal London residence and the heart of the government’s executive powers. Beyond that lay Westminster, where Parliament sat in a former royal palace.

The river linked these centres of power and offered the easiest way to travel from one to the other. Around them, the suburbs expanded steadily. London Bridge – at this time, the only bridge below Kingston, ten miles upstream – linked the City to Southwark, itself as large as many seventeenth-century cities, on the south bank of the Thames. The river was also the main artery for trade, both domestic and foreign.

Charles II regained his throne in 1660 amid scenes of almost universal jubilation. In the previous twenty years, hundreds of thousands had died in the Civil War between Crown and Parliament, including Charles’s own father, executed with a nice sense of symbolism in front of his own Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace. Afterwards, sustained by the army, Oliver Cromwell ruled the country with ruthless and bloody efficiency. When Cromwell died in 1658, however, the Commonwealth rapidly crumbled, and a restored monarchy seemed the only practicable way to heal the country’s divisions.

Six years later, the jubilation had subsided. The King’s profligate court horrified and angered his more sober subjects. Religion was a constant source of conflict – the Anglican establishment, restored with the King, nursed a deep distrust of the dissenting Protestants who had formed the core of Cromwell’s support. Both parties loathed the Catholics, who in popular imagination were associated with conspiracies at home and implacable, devious malignity abroad. The government was chronically short of money, which hampered its policies at every turn. To make matters worse, the plague struck repeatedly at the capital – in 1665, its most virulent outbreak, the mortality rate was an extraordinary one in five.

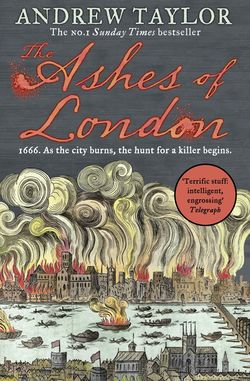

Still, somehow, London grew and prospered. Then, on 2 September 1666, the Great Fire began to burn in a baker’s shop in Pudding Lane, deep within the densely populated heart of the old City.