Читать книгу Fatal Judgment - Andrew Welsh-Huggins - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление9

I PUT THE CAT’S food bowl and water dish on my kitchen counter, out of reach of Hopalong’s vacuum-like appetite. The cat’s back went up immediately when it spied the dog, whereas the Lab spent all of twenty seconds staring at it curiously before retreating to the couch. So hopefully there would be something left of my house when I returned.

Thirty minutes later I was pulling into a gravel parking lot framed by weathered split-rail logs half a mile off Sawmill Road on the northwest side. Even with a stand of maples lining the entrance behind me it was still possible to see the orange corner of a Home Depot a few hundred yards away. The rush of traffic on Sawmill was distinct, like an incessant breeze, and a smell of cooked meat wafted in from a nearby McDonald’s. A wilderness this was not. This was a petunia in an onion patch operated by an agribusiness. Just standing there glancing at the trees ahead of me, I could understand both sides’ arguments. For a developer, this acreage was a lost cause whose fate was being sealed by the growth around it one load of hot, steaming asphalt at a time. Why not call it a day, especially since the world would get an even bigger swamp in return? For an environmentalist, these fields and forest were a last stand whose fate would determine how society dealt with nature on the brink. Why not save it, since no one could plausibly argue the world needed one more strip plaza anchored by a Starbucks on one end and a Verizon store on the other? I didn’t envy Laura her decision.

I followed a packed dirt trail through the woods, noticing how the sounds of the outside world diminished the farther I walked, traffic noise dimming just a little and the smell of frying meat gone altogether, replaced by a mossy, wet odor that took me back to patches of forest on my uncle’s farm that my sister and I explored for hours as kids. After ten minutes of steady hiking I stepped onto an elevated boardwalk at a break in the woods. I read a marker that explained the biological diversity present in the swamp ahead of me. Herons, cranes, and hawks hunted there. Numerous songbirds called it home, including the coastal tanager, a Brazilian native that migrated north and summered in the few remaining swamplands that it favored. I looked up, hoping to glimpse the bird, but detected only a flutter of wings that could have been anything from a sparrow to a mourning dove.

I walked along the boardwalk toward the swamp. Just as I fostered the fantasy of seeing Laura in her home office when I entered her condo that morning, I imagined seeing the judge round the corner ahead of me, a smile on her face as she congratulated herself on luring me to a romantic rendezvous with a clever collection of verbal and handwritten clues. But no one was there. I walked another hundred yards until the walkway ended at an expanded platform overlooking a small pond at the heart of the park.

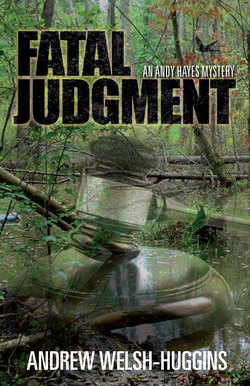

I put my hands on the rail running around the platform and gazed over the water, which was dark and brackish, its edges coated with algae like brushstrokes of undulating green batter. At my approach sunning frogs catapulted themselves into the water with a pitter-patter of splashes. Below me a mud-brown water snake glided into the depths in pursuit of lunch. On the far side of the pond a small stand of reeds was encroaching into the water. Something in the middle caught my eye. What I’d first mistaken for another pair of reeds were the legs of a heron. The bird stood motionless at the edge of the plants, head slightly lowered. I looked closer and saw just a few feet away another frog, this one sitting atop a lily pad, facing the opposite way, oblivious to the danger directly behind it. The heron extended its neck almost imperceptibly, raised a stick-like leg, and advanced noiselessly a few inches in the water. The frog didn’t move. I was torn between clapping my hands and giving the little guy a chance and doing nothing and watching the circle of life unfold in all its cruel efficiency. I chose the latter, for better or worse. The heron took another step, and then a sound behind me interrupted it, the creak of a loose board on the observation deck, and the frog disappeared with a splash and I turned and reflexively stepped back as the knife in the hand of a man crouching behind me bit into air instead of my rib cage.