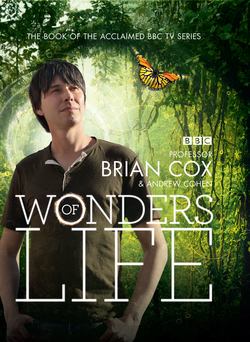

Читать книгу Wonders of Life - Andrew Cohen - Страница 6

ОглавлениеThe Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman used to tell a story about an artist friend who challenged him about the beauty of a flower. ‘You as a scientist, oh, take this all apart and it becomes a dull thing’ he said. Feynman, after describing his friend as ‘kind of nutty’, went on to explain that whilst the aesthetic beauty of nature is surely open to everyone, albeit not in quite as refined a way, the world becomes more beautiful as our understanding deepens.

The flower is made up of cells, single units with identical genes. Hidden within are a multitude of biochemical machines, each highly specialised to perform complex tasks that keep the cell alive. Some contain chloroplasts, once free-living bacteria, co-opted into capturing light from the Sun and using it to assemble food from carbon dioxide and water. There are mitochondria, factories that pump protons up energy ‘waterfalls’ and insert organic waterwheels into the ensuing cascade to assemble ATP molecules – the universal batteries of life. And there is DNA, a molecule with a code embedded in its structure that carries the instructions to assemble the flower, but also contains fragments of the story of the origin and evolution of all life on Earth, from its beginnings 3.8 billion years ago to the endless forms most beautiful that have transformed a once-sterile world into the grandest possible expression of the laws of nature. This is beauty way beyond the aesthetic that, as Feynman concluded, ‘only adds to the excitement and mystery and the awe of a flower. It only adds; I don’t understand how it subtracts.’

I confess that, when we began thinking about filming Wonders of Life, my knowledge of biology was a little dated – I gave it up as an academic subject in 1984. As I recall, the idea for the series came from an off-hand reference I made to Andrew Cohen about a little book I had read as a physics undergraduate.

What is Life? is an account of a series of lectures given by the physicist Erwin Schrödinger, published in 1944. Schrödinger was a Nobel Prize winner, one of the founders of quantum theory, and a deep and high-precision thinker. In the book, he poses a simple yet profound question: ‘How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?’ This question is beautifully phrased. Most important is the word ‘How’ at the beginning. Without this word, the question is metaphysical, in the sense that the answer may be ‘No’ – a complete understanding of life may be forever beyond the natural sciences because there is something inherently supernatural about it. The word ‘How’ transforms it, and provides a significant and important insight into the mind of a scientist. Let us find out, by studying nature, developing theories and testing those theories against our observations of the living world, how life can be fully explained by the laws of physics and chemistry, as it surely must be. This, I submit, is an excellent description of the science of biology.

Wonders of Life might be best described as a series exploring our current understanding of Schrodinger’s ‘How’ question. I enjoyed making the films immensely, because virtually everything in them was discovered after I gave up biology in 1984. The rate of discovery, driven by powerful new experimental techniques such as the exponentially increasing ease and decreasing cost of DNA sequencing, is quite dazzling and, Higgs Boson notwithstanding, I might be convinced that the 21st century has already become the century of the Life Sciences; but only ‘might’.

A truly wonderful exception to the modernity is Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, published in November 1859 and spectacularly verified as a conceptual framework to understand the diversity and complexity of life on Earth. To understand Darwin’s genius, look out of your window at the living world. Unless you are in the high Atacama Desert, you will surely see a living world of tremendous complexity. Even a blade of grass should be seen through Feynman’s reductionist prism as a magnificent structure. On its own, it is a wonder, but viewed in isolation its complexity and very existence is inexplicable. Darwin’s genius was to see that the existence of something as magnificent as a blade of grass can be understood, but only in the context of its interaction with other living things and, crucially, its evolutionary history. A physicist might say it is a four-dimensional structure, with both spatial and temporal extent, and it is simply impossible to comprehend the existence of such a structure in a universe governed by the simple laws of physics if its history is ignored.

And whilst you are contemplating the humble majesty of a blade of grass, with a spatial extent of a few centimetres but stretching back in the temporal direction for almost a third of the age of the Universe, pause for a moment to consider the viewer, because what is true for the blade of grass is also true for you. You share the same basic biochemistry, all the way down to the details of proton waterfalls and ATP, and much of the same genetic history, carefully documented in your DNA. This is because you share a common ancestor. You are related. You were once the same.

‘How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?’

Erwin Schrödinger

I suppose this is a most difficult thing to accept. The human condition seems special; our conscious experience feels totally divorced from the mechanistic world of atoms and forces, and perhaps even from the ‘lower forms’ of life. If there is a central argument through the five films and chapters in Wonders of Life, it is that this feeling is an emergent illusion created by the sheer complexity of our arrangement of atoms. It must be, because the fundamental similarities between all living things outweigh the differences. If an alien biochemist had only two cells from Earth, one from a blade of grass and one from a human being, it would be immediately obvious that the cells come from the same planet, and are intimately related. If that sounds unbelievable, then this book is an attempt to convince you otherwise.

I write this in full appreciation of the so-called controversy surrounding Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. My original aim was to avoid the matter entirely, because I think there are no intellectually interesting issues raised in such a ‘debate’. But during the filming of this series I developed a deep irritation with the intellectual vacuity of those who actively seek to deny the reality of evolution and the science of biology in general. So empty is such a position, in the face of evidence collected over centuries, that it can only be politically motivated; there is not a hint of reason in it. And more than that, taking such a position closes the mind to the most wonderful story, and this is a tragedy for those who choose it, or worse, are forced into it through deficient teaching.

As someone who thinks about religion very little – I reject the label atheist because defining me in terms of the things I don’t believe would require an infinite list of nouns – I see no necessary contradiction between religion and science. By which I mean that if I were a deist, I would claim no better example of the skill and ingenuity of The Creator than in the laws of nature that allowed for the magnificent story of the origin and evolution of life on Earth, and their overwhelmingly beautiful expression in our tree of life. I am not a deist, philosopher or theologian, so I will make no further comment on the origin of the laws of nature that permitted life to evolve. I simply don’t know; perhaps someday we will find out. But be in no doubt that laws they are, and Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is as precise and well tested as Einstein’s theories of relativity.

If this sounds a little strong, then perhaps it reveals my genuine excitement in learning about the sheer explanatory power of Darwin’s theory when coupled with recent advances in biochemistry and genetics. Modern biology is close, in my view, to answering Schrodinger’s ‘How’ question. There are unknowns to be sure, which is what makes the subject of these films doubly exciting. Some parts are speculative, but that is nothing to be ashamed of in science. Indeed, all science is provisional. When observations of nature contradict a theory, no matter how revered, ancient or popular, the theory will be unceremoniously and joyously ditched, and the search for a more accurate theory will be redoubled. The magnificent thing about Darwin’s explanation of the origin of species is that it has survived over a hundred and fifty years of precision observations, and in that it has outlasted Newton’s law of universal gravitation.

My favourite moment in the series is the final scene of the final film, which unusually, was filmed on our final evening; television shows are rarely made in chronological order. We found a tiny rocky island off the coast of northern Madagascar, no bigger than the average suburban garden, isolated in the warm waters of the Mozambique Channel. The idea was to sit down and chat about the experience of making the series, and film the result. I won’t tell you what I thought and said, because that should wait until the end of the book. But I do want to say one thing here in the introduction. I recall a conversation in March 2009, just before we started filming Wonders of the Solar System. Andrew, my co-author and executive producer, said that we would have achieved our goal if those who watched never again looked at the night sky in quite the same way. This is in the spirit of Feynman’s flower. Deeper understanding confers that most precious thing – wonder. A sky filled with tiny, twinkling lights is one thing, but a sky filled with other worlds is quite another. I have known this for virtually all my life, because I have always been an astronomer at heart. Perched on my island, thinking about what to say, I realised that I now felt precisely the same about a single blade of grass.