Читать книгу Rabbit and Robot - William Hughes, Andrew Smith - Страница 16

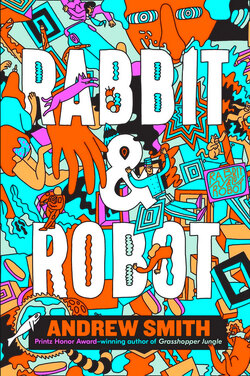

Rabbit & Robot

Оглавление“Happy almost-Crambox Eve, Cager,” Billy said.

“Fuck, Billy. Why are you guys doing this to me?” I needed to vomit.

Puking in space is not good; just ask anyone who’d survived the Kansas ordeal.

In the absence of gravity, sewage, like hungry tigers and venomous snakes, is incomprehensibly terrifying.

The transpod shuddered and roared as it picked up acceleration down the railway of the takeoff strip. Rowan turned his face toward us and watched what was going on. I could tell he felt bad for me and Billy, so there was a lot of feeling miserable going on in first class.

Except for Lourdes, our flight attendant, who squealed, “Whee! Whee! I am so happy! I am so happy! I could poop myself, I’m so happy! Whee!” From her rear-facing seat, she paddled her high-heeled feet as though she were doing the backstroke.

I couldn’t help but catch a glimpse of her panties.

“Well. I thought it would be a nice gift for you, Cager. You know. Just us—well, and Rowan, too—up there on that enormous ship, where we can do whatever we want and basically run the place. Think of it, how much fun that will be.”

“Yeah. Whatever, Bill.”

“Come on. It will be great. Tell him how fun it will be up there, Rowan,” Billy said.

“You may never want to come back,” Rowan confirmed.

The transpod got noisier and noisier as it approached liftoff speed.

My hand trembled next to Billy’s on our armrest. I watched as my skin drained to the color of skim milk. I felt terrible, so I grabbed Billy’s hand.

And I’ll admit the truth: When a Grosvenor Galactic cruise transpod lifts off, there are undeniable moments of terror. The noise is so tremendous that you can’t hear the other passengers scream, which they always do (and Billy, who had never traveled to space, was doing right now), and the entire craft shakes like it’s about to fall to pieces. And then there’s that instant when your feet are pointing directly upward and your head fills to capacity with whatever blood was previously circulating in your system. Thankfully, it’s all over in a minute or so, and then you’re just floating along in silence—and if it’s your first time up there, chances are you’re wondering if this is what death is actually like.

Billy Hinman’s fingernails dug into my hand.

“This may have been the dumbest mistake I’ve ever made,” he said. “Get me down.”

“Ow,” I said. “Your fingernails are sharp.”

Rowan’s expression showed a bit of concern—possibly worry—over how I was handling my abduction. And then Rowan said the worst thing imaginable, which was this: “It’s all perfectly smooth sailing now, Billy. Look at how high we are.”

Rowan extended his hand toward the porthole.

Billy Hinman, who was terrified of flying, groaned. He fired a dirty look at Rowan, and that’s when he said good-bye to Earth, and to California.

Billy opened a rectangle between his hands, and his thumphone screen hovered in the air above his lap. I watched without saying anything as Billy Hinman attempted to call his dad, who was somewhere in India.

There was nothing. No message, no fake ringtone. Only static. It was weird, and it made me want to try my phone too, or at least offer to loan mine to Billy, because Hinsoft thumbphones worked everywhere—even in space. But I pretended not to pay attention to what Billy was doing, even though I obviously was doing exactly that.

Billy closed out the screen and said, “Fuck this, stupid no-signal in space.”

Behind us, one of the attendants in second class screamed and cried about being unfairly persecuted by a bigoted passenger.

Being on a transpod was almost like being stuck inside Gulliver’s Travels, I thought. I imagined that if I’d spent a few days in second class, I’d come out acting like the raging flight attendant behind us. As it was, I could only hope that being in the front affected all of our moods in a more positive way.

Lourdes unhooked from her seat and gleefully announced that she would begin in-flight service and entertainment. She activated the transparent screenfield at the front of the cabin and said, “I am thrilled to present our in-flight entertainment selection for first-class passengers on R&R Grosvenor Galactic! Our feature will begin after a brief advertisement! I love this so much!”

Lourdes’s face scrunched and she farted. Then she danced. With no music, and for no reason at all that any of us could figure out.

V.4 cogs can fart. There is no Woz in space. Another war was bound to begin on Earth—it was only a matter of time—while the first one between Billy Hinman and Cager Messer was just getting started somewhere between home and the moon.

I did not want to speak to Billy Hinman.

I knew our trip would be tough. There was no turning back, even if I tried using the no-credit-limit impact of my name. And although there was something especially painful in knowing that my best friend was trying to do something nice and positive for me, it was something I didn’t want anything to do with. So I found myself pendulum-swinging between regret for being angry at Billy and trying to rationalize the truth that if he’d have let me alone, I would not have lived much longer. I suppose that was selfish of me. And it seemed that every beating I’d ever received at the hands of my mother or father always included some type of it’s-for-your-own-good justification, which I knew was bullshit. Just like I knew that what Billy Hinman was doing to me was bullshit too.

Not surprisingly, the brief commercial that played before our in-flight entertainment was produced by Hinsoft International. It was a sure bet that the next advertisement on the flight would be from a Grosvenor brand. After all, there was almost nothing at all in existence that didn’t come from the guys whose sperm made me and Billy Hinman.

The Hinsoft ad was all about the New! Revolutionary! v.4 cog, and how seamlessly it blended in to the human world—satisfying the demand for anything people no longer wanted to waste their time doing, which was just about everything you could list, besides being a bonk, a coder, or maybe a department store Father Christmas. The commercial showed happy cogs, which I was already getting sick of after spending about forty-five minutes with Lourdes, shouting cogs, a chorus line of singing cogs, cogs performing surgery on human beings, road-building cogs, and even naked ones. It was perfectly okay to show full nudity in public media displays—as long as the nakedness in question involved unclothed cogs, who were strikingly anatomically correct—because, after all, cogs were cogs. It was like looking at a Renaissance sculpture of a Greek god or some biblical character’s penis or breasts. It was actually like looking at a naked electric toaster, when you thought about it. As long as they weren’t actually people, everyone was pretty much okay with whatever cogs did.

And the commercial’s British-accented and most likely cog narrator said, “Hinsoft v.4 cogs—so lifelike and functional, so smart and reliable, you might find yourself falling in love.”

Wonderful, I thought.

The more disturbing thing was what followed the v.4 ad. What came next was an episode of Rabbit & Robot.

Billy Hinman perked up from the melancholy that pervaded our cabin. He had an almost conspiratorial look on his face. Neither of us was ever allowed to watch my father’s program, so this was like sneaking a drink or a smoke, except those were things that Billy Hinman and I did whenever we wanted to. Watching Rabbit & Robot, on the other hand, was entirely forbidden in the Messer and Hinman households.

I glanced over at Rowan. “Hey!”

Rowan said, “Would you like me to have Lourdes turn it off?”

Billy answered, “No. We’re stuck and there’s no turning back at this point. I want to see it.”

And on came the opening song. It was meaningless and absurd, sung as a duet by Rabbit, the bonk, and Mooney, the cog, but for whatever reasons it brightened my mood. I think it was most likely the case that if there was such a thing, the song was written in the key of Woz, since everyone who was addicted to the program was also, like Cager Messer, addicted to Woz.

Oh, Rabbit and Robot, Robot and Rabbit

Behind your eyes, the kingdom we inhabit!

The land of asynchronous transfer mode,

Go fight wars, and write that code!

Oh, Rabbit and Robot, Robot and Rabbit

Oh, Rabbit and Robot, Robot and Rabbit

Oh, Rabbit and Robot, Robot and Rabbit

Oh, Rabbit and Robot, Robot and Rabbit!

Like I said, it was really dumb, to the point that I felt uncomfortable—embarrassed, even—because I always knew Rowan was exceedingly judgmental about stupid shit. And there was no getting around it here. But I liked it. It made me happy. Just as Billy said, we were stuck on this shit ride.

And while Mooney and Rabbit—and Lourdes—sang to us, a shotgun storm of images blasted all around the screen—scrolling strings of code commands, and short staccato clips of bonks doing what bonks do, the types of things that were big thrilling hits at Charlie Greenwell’s “engagement parties.”

The last time we’d been to Charlie’s apartment on a Woz buying mission, Charlie Greenwell told us this: “Every week or so, the boys in my unit would get together and drink and get hacked on Woz, and we’d tell our stories about the people we’d killed in engagements. That’s what we called ’em—engagements. It was an engagement party. Ha ha!”

“Yeah. Funny,” Billy had said, completely deadpan.

“I’m not lying,” Charlie said.

Neither one of us thought Charlie Greenwell was lying. I could smell the runny eggs Charlie Greenwell had eaten that morning for breakfast, and that he’d drunk some vodka too. It kind of turned my stomach.

“And I’m not embarrassed to say what happened, either,” Charlie said. “But, you know, it was weird, but that’s what we were there to do. Twenty-seven wars don’t just fight themselves, you know?”

“Twenty-eight,” Billy corrected.

“What fucking ever, Hinman,” Charlie said. “Anyway, it was how we blew off steam—telling about all the rabbits we’d shot, and what it was like. And I ain’t lying, neither, but most of us bonks would get pretty worked up after a few hits and all the stories we’d tell about whacking rabbits. Most of us got pretty horned up just thinking about it.”

“Wait, wait, wait,” I said. “You fucking got horny while telling stories about killing people?”

“Well. Yeah. It was no big deal, Hinman. Everyone does,” Charlie said.

I could only imagine Charlie Greenwell had no clue about what everyone did, and now there he was, back in the good old United States of America, smoking Woz with me, and walking down the same streets and visiting the same shopping malls as everyone else.

Charlie Greenwell was on state disability. Everyone in America who was old enough to work was either a bonk, a coder, on disability, or maybe on disability and doing part-time gigs as human department-store Santas, or completely invisible, except for people like Billy and me, and that was just because of our parents. It had nothing to do with us.

Rabbit & Robot turned out to be meaningless and riveting at the same time. There was something about the song and the images that seemed to connect directly with the Woz receptors in my brain.

I always knew this was why Billy and I had been kept away from the show—and supposedly from Woz—for our entire lives.

When the assault of the song and pictures finally ended, and the quiet opening of the first scene replaced it, I felt my shoulders relax. I slumped comfortably back in my seat.

“I love this show! I love this show so much, I want to rip my clothes off and rub Rabbit & Robot all over my naked body!” Lourdes gurgled. Her hair was a mess, and her skirt had twisted around, due to all the wild dancing she’d been doing. If she were a human, she would have been soaked in sweat, and quite possibly ashamed of herself too.

But I love v.4s, even if I was calculating in my mind how unbearably long the two-day journey to the Tennessee would actually be with Lourdes running as juiced-up as she was.

Rowan shrugged and shook his head.

If the opening song was stupid, the episode of Rabbit & Robot we watched adequately matched or exceeded that quality.

The episode we saw—well, the one I saw, since Billy Hinman was obviously trying to force himself to not watch it—was about a mistake that had been made with Mooney’s work classification. He had been drafted into the army, which made Mooney the cog very confused, and Rabbit the bonk extremely angry.

But Mooney, being the patriotic and dutiful cog that he was, reported to boot camp along with his partner, Rabbit (which didn’t really make sense, since Rabbit was already an accomplished bonk, but sense making was not something the program was necessarily praised for), and zany high jinks ensued. And even though nearly every episode of Rabbit & Robot included Mooney’s violent destruction at some point, people regularly told us how hilarious it was, and lavished us with undeserved vicarious praise for our television-program-and-spaceship-producer and cog-and-thumbphone-manufacturing sperm-donor fathers. When the other bonks in Mooney’s squad at boot camp found out they were sharing their barracks with a cog, they were understandably outraged. They found out because Rabbit outed Mooney when he was drunk, which was something Rabbit routinely was in the show too.

Oops.

So the other bonks in Mooney’s squad waited until after lights-out was declared and, on the third night of boot camp, dragged Mooney the cog outside and set him on fire while he screamed and screamed. Actually, they set him on fire after cutting off his arms and legs so he couldn’t run away or attempt to pat out the flames with his cog hands. It was all very funny, especially when the bonk recruits began singing a bonk song called “Making Rabbit Stew.”

Everyone knows that it is barbaric and uncivilized to allow cogs to participate in the glories of human warfare. What purpose could that possibly serve? Nothing would ever get solved if people let wars just fight themselves.

Even Charlie Greenwell knew that.

Cheepa Yeep!