Читать книгу The Alex Crow - William Hughes, Andrew Smith - Страница 12

SCARY STORIES

ОглавлениеLet me tell you this, Max: When I came out of the refrigerator, there honestly was no place for me to stay. I had to go along with the soldiers who’d come to the village after the gas attack.

They were nice to me, anyway. I think it may have had something to do with the clown suit—how it made me look like a baby, even if I had just turned fourteen. Although they smoked, they never offered their cigarettes to me.

It seems so long ago, Max. It’s why I tell you it was my first life, as though I had been resurrected at some point—at least once—before we ever met.

I asked Thaddeus, the man who’d taken off his mask first, if it was the Republican Army who’d gassed the village, and he told me, no, that it was the FDJA rebels. What else would he say? Depending on how long I’d actually been inside that refrigerator, there were probably dozens of videos that had already been posted on the internet assigning blame to any imaginable party. And everyone knows whichever video scores the largest number of hits would be the one that tells the true story, right?

So I went with Thaddeus.

We rode in the open back of a dusty troop carrier with nine other soldiers. Our truck drove in a convoy of military vehicles, some of which towed weapons that looked like missile launchers. Although there was a metal frame to support a canvas covering for our truck’s bed, there was no tent, so we all sat there exposed to the heat, dust, and sun. The men were so tired they slept in the rattling bed, slumped over wherever they fit. The soldiers lay atop coiled serpents of ammunition—bands of oily bullets as long as my forearm. The men were uninterested in me, or how I’d come to be there dressed as I was.

But Thaddeus was nice to me. He’d told me that he had two sons at home, and he promised me that everything would work out for me now that I was safe and away from the village. He shared his water and food with me.

In the afternoon we rode through another small city. I did not know the place; I had never been there. But when the convoy drove down the main avenue, the people lined the street and crowded the balconies above to watch us. It was so quiet, or maybe it was just that any sound the people may have been making was drowned out by the clank and roar of our convoy.

Young men followed along on motorbikes and scooters, or they ran like snakes along the crowded sidewalks, as though it were a sort of festive parade, and this was the best thing that had happened in memory.

From time to time jets flew by, low in the sky overhead. We could hear the explosions from the missiles they fired miles ahead of us, beyond flat farmland and low mountains.

That night we slept outside on a dirt road that ran through a sesame field.

I woke sometime in the darkest part of the night. There was no moon, only stars. I didn’t know it, but Thaddeus had been sitting next to me, watching me as I slept. He’d given me a blanket to lie on, and it was so warm that I was damp with sweat.

“Are you all right?” Thaddeus asked.

“Yes. It’s hot, and I’m not very tired.”

“Can I tell you something?” he said.

“Sure.”

“It’s not a good thing,” Thaddeus said, “but I feel I need to tell somebody. And I think you’re the person to say it to.”

“Why me?”

Thaddeus shook his head. “I don’t know. Maybe it’s the white suit.”

“It’s not as white as it was when I put it on,” I said.

“No matter,” Thaddeus said.

He scooted toward my blanket and leaned close, so he could whisper. “When I was a boy—I was—how old are you?”

“Fourteen.”

“You’re fourteen?”

“Yes.”

“I thought you were just a baby.”

“Maybe it’s the white suit,” I said.

Thaddeus nodded. “When I was nine years old, my mother became very sick with cancer. She was dying. It was terribly slow and ugly to witness. My father never talked to me about it. Not one time did he ask me how I was feeling, or what I was thinking about. Do you know?”

“I think so.”

“I was so angry about everything, but my father never spoke to me about it.”

“It must have been sad. I don’t have any parents, and now my aunt and my uncle—”

“Yes. Maybe that’s why I need to say this.” Thaddeus leaned toward my shoulder. His breath was hot as he whispered. “We had a small dog then. His name was Pipo.”

“That’s a good name.”

“I was so mad about everything. Outside our house, there were fields of wheat growing. One morning, I took Pipo into the field and dug a deep hole. Then I put the little dog in the hole and I buried him. Nobody knew what I did. That evening my father asked where the little dog was, and I lied to him and told him I didn’t know; that maybe he ran away. It was a terrible thing. I feel so bad about what I did. I think about it every day.”

I could see Thaddeus was crying.

“I never told anyone about it until now. I was a monster, but I couldn’t control myself.”

“Maybe that little dog was the only thing you could control.”

“I hate myself still.”

What could I say to the man? It was almost as though, in the telling, he were pouring the story of the little dog into me—this receiving vessel dressed in a clown suit—and now it would be my responsibility to carry Thaddeus’s story along with me for how many more years.

“Eventually, I suppose you’ll have to find a way to make things right,” I said.

“That’s why I’m telling you. You need to say how I can do this.”

“Why me?”

“Because, when I found you, it was as though you’d come out of a hole,” Thaddeus explained.

I shrugged.

“It was a refrigerator. I needed to pee.”

- - -

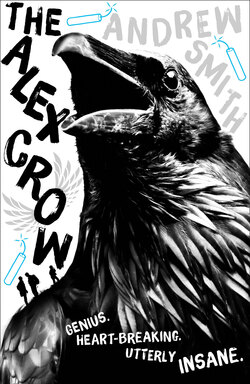

Jake Burgess worked in a semiautonomous laboratory owned by the Merrie-Seymour Research Group. It was called Alex Division. This is where nearly everything Jake Burgess invented came from, including our pet, Alex.

Jake always had a fascination with crows. He told me it was due to the birds’ uncanny intelligence and their ability to adapt to just about any situation that confronted them. The first Alex crow was a gift from Jake to Natalie just after the birth of Max, my American brother, who did not like me and was exactly sixteen days older than I was.

I say “first” Alex because that bird died when Max was ten months old and I lived in a dirty village halfway around the world from Sunday, West Virginia. Well, to be honest, the crow only sort of died when Max and I were ten months old.

Jake Burgess brought both of the Alex crows back to life. They were like photocopied beings that would never change, and never leave. Alex, our crow, was a member of a species that had been extinct for a century.

At that time, my father, Jake Burgess, was investigating a method for perfecting de-extinction for Alex Division. Of course, both the word and the concept of de-extinction are entirely ridiculous.

Extinction can’t be undone, or else you were never extinct in the first place. You were just waiting for something better than eternal death.

There was always something a little off about the things Jake Burgess brought back to life. At least, that’s what Max told me. I couldn’t exactly say I knew any of the other Alex animals created by Jake Burgess, so I had nothing to compare our pet to. Still, our resurrected pet bird did strike me as being empty of any kind of soul, and overwhelmingly disappointed by his existence.

Sometimes I wondered if Max had been emptied out and brought back to Sunday just like Alex, in some cruel experiment researched by his father, or that perhaps I had been brought back like our crow, too.

It’s funny how I remember some events in my life so clearly, and others—often recent ones—seem disjointed and fuzzy. I attribute that to nervousness, I suppose. It’s a very frightening thing, when you think about it, being dug up from a hole or extracted from a refrigerator and then finding yourself some kind of display artifact for everyone to marvel over (See the kid who shouldn’t actually be here!). But I can’t clearly remember all the details surrounding my arrival at the Burgess home in Sunday. I remember riding in a van with Jake Burgess and a man named Major Knott from a place called Annapolis, which I had never heard of before. Also, I remember all the trees and water—we crossed so many rivers on the way—things I’d only seen in pictures.

The Burgess house was a single-story brick home built into a hill with a garage and basement underneath the main floor. We walked up a gravel driveway to the front door, where Natalie and Max—who had taken the day off from school to meet his new foreign brother—waited.

Natalie held my face and kissed me on top of my head. It made me feel nice.

And Max said to me, “What’s your name, kid?”

“Uh.”

Natalie patted Max’s shoulder. “Don’t be silly, Max. We’ve told you. His name is Ariel.”

Max said, “Oh yeah. Ariel,” and walked away.

But they pronounced it correctly.

I went inside with Jake Burgess and Major Knott, who carried a cloth bag containing the new clothes and things they’d given me when I got to Annapolis. The house was dark and smelled like nothing I had ever smelled before. It was the smell of America, I’d supposed, a combination of furniture polish, cleanser, and cooking oil.

In the living room, behind an old tufted chair, stood a type of black rounded perch. And on that perch was the Burgesses’ crow, Alex. He was staring at me, holding perfectly still. I honestly thought he was some sort of decoration; I never imagined people kept such creatures in their homes.

But then Alex moved his head slightly and said, “Punch the clown. Punch the clown.”

It was nothing more than a frightening coincidence. Eventually I came to realize Alex learned much of his vocabulary from Max.

- - -

Joseph Stalin was not the only voice inside Leonard Fountain’s melting head. The melting man also heard someone named 3-60.

3-60 was not as mean or harmful as Joseph Stalin. While Joseph Stalin urged Leonard Fountain to kill people, 3-60 said nice things to the melting man. 3-60 liked to narrate to Leonard Fountain everything that he was doing, as though she were telling the story of the melting man’s life while it played out in real time.

“You are turning onto Smale Road.”

“Yes. I am,” the melting man said to 3-60.

“You are driving past a cemetery. You are looking at the headstones. Your balls are itchy. You are drifting off the road.”

The melting man swerved back onto the highway.

“Thank you for saving my life, 3-60.”

“You’re welcome, Lenny.”

That reminded the melting man of his younger brother, who was the only person who’d ever called him Lenny.

“But your balls still itch,” 3-60 reminded him.

“Oh yeah.”

“Now they hurt.”

“Well, I shouldn’t have scratched them,” the melting man said.

“You’re very sick,” 3-60 told him. “Maybe you should consider leaving the masterpiece somewhere along the side of the road and just moving on.”

“I have to do what Joseph Stalin told me to do. I don’t want to make him angry.”

“You are driving. You are driving. You are driving,” 3-60 said.

“Yes. I am.”

Tuesday, February 17, 1880 — Alex Crow

While the Alex Crow sank, the crew managed to pull two of the ship’s longboats, as well as the dog sleds, food, and equipment from the doomed vessel.

Mr Warren could not assist the off-loading due to his incapacitation. However, in this past week, Mr Warren’s hand has healed significantly, although he has lost a great deal of mobility due to the shattered bones. Imagine the predicament of a newspaperman who lacks the ability to put pen to paper! Mr Warren has been dictating to Murdoch, but the man is constantly frustrated by Murdoch’s deficiencies in skill.

Let me express how disheartening it was to see the last timbers of the Alex Crow being shut up behind the mouth of this hellish Arctic ice. It was a mournful event for us all, because despite our predicament there was always some insulating sense of safety provided to our little society by the formidable ship. Now we are stripped of nearly everything and left to make some way, which I fear is only a lengthening of our journey toward doom. I cannot believe any of us will survive now.

After a full day’s rest on the ice pack, Captain Hansen and Mr Piedmont calculated a direction for our attempt at reaching the New Siberian archipelago. The journey has been incredibly arduous—the men work without rest, dragging the burdensome boats over impossible crags of relentless ice. Two days ago, on Sunday, it seemed as though our party had only managed to cover a few hundred feet for the entire day’s labor.

The cost on the men has been significant. Yesterday morning, Mr K. Holme, a naval seaman, succumbed to the cold, and today our expedition’s ice pilot, Edgar Baylor, passed away shortly after dawn.

Our crew has lost all hope of rescue. I am afraid that if there was any reasonable alternative to Captain Hansen’s strategy to reach New Siberia, there certainly would be mutiny among the survivors.

Sunday, February 22, 1880 — Alex Crow

A most remarkable occurrence—we reached open water today!

Could it be that those of us who have endured this ordeal will survive? Mr Murdoch during this past week has taken to uttering a repetitive chant of sorts—“Why bother?” he asks again and again. It does give one pause, at times, to consider the point of it all. Why is the will to survive—in spite of the horrors of one’s condition—so profound?

Why bother?

It was entirely unbelievable. When we saw the dark breach ahead of us, Captain Hansen and Mr Piedmont presumed we were approaching Kotelny Island, and that what we saw must have been the rocky shore. This proved to be incorrect as we neared the edge of the ice pack.

So it was with renewed spirit the men bothered to lower the heavy longboats into the sea. The dog teams, however, were forced to turn back in the direction from which they’d come, since there was not adequate room on our boats for everything. I sensed some great relief among the native handlers when they were finally free to leave our ill-fated expedition.

I am in Captain Hansen’s boat. I believe that his leadership has kept the majority of the expedition alive during the difficult journey across the ice, and I have faith that he will bring us safely to the shores of the northern islands where we will find shelter and warmth among the natives there.

This is my hope.

Tuesday, February 24, 1880 — Alex Crow

We lost sight of our sister boat in a vicious storm last night.

One more of the seamen—Richard Alan Culp—died aboard our vessel this afternoon. Once again, our diminished party feels alone and without hope. It is all I can do to tend to their aching bodies, and attempt to inspire some sense of confidence and optimism. I’m afraid this is entirely useless, though. The least I can do is to ignore the constant questioning of Murdoch.

This afternoon, Mr Warren and I huddled beneath the gunwale in a small covered space we’d made with one of the expedition’s tents. I’d asked him if he was still dictating the narrative of our expedition to Murdoch. He insisted that readers would want to have the full account of the loss of the Alex Crow, even if none of us survived.

“Particularly if none of us survive,” I said.

To this, Mr Warren replied, “I cannot think any of us will ever see his home again. Why would anyone think such a thing, given our current state?”

I do not believe we can last one more night in this boat. I have found myself hoping—and that is an odd word to use—that I will not wake to find myself the sole living inhabitant of the boat, that if I am not to make it home again, as Mr Murdoch predicts, that I die before too many others are dropped into the sea.

I realize that death and survival are both extremes of selfishness.

Just before nightfall, from beneath our covering, Mr Warren and I heard Murdoch shouting that land had been sighted, but when we came out to look, it was already too dark to see anything more than an arm’s reach from the boat’s hull.

Imagine our disappointment and dread at Captain Hansen’s cautious decision to forego any attempt at landing until daylight tomorrow.

“Who knows where we will be at daylight tomorrow?” Murdoch wondered.