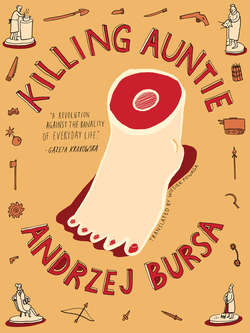

Читать книгу Killing Auntie - Andrzej Bursa - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

EVERY TIME I OPENED MY EYES IN THE MORNING AUNTIE was already on her feet. Humming in her low alto voice, she bustled around the stove, preparing our breakfast. The simplicity and good nature of this woman was too much of an everyday occurrence to make any impression on me. Nevertheless, from time to time, there were moments it moved me, though more often recently it irritated me. Auntie earned her living as a sort of middleman in the local wool trade or some such business; I was never really interested in that. She worked like a dog.

Apart from myself, a twenty-one-year-old loafer, Auntie also provided for her old mother and her crippled sister. Both lived in a remote small town in the mountains. They visited us more than four times a year. I hated those visits. When Granny, wrapped up in black frocks, her ears all smeared with some white pasty medicine, sat at the table, it was revolting. I felt even more disgust toward her daughter – a young apathetic hunchback with coke-bottle spectacles. They were both very devout and crossed themselves eagerly before every dish. Auntie, once a beautiful and worldly woman, with them suddenly remembered which church she belonged to. The dinners were better then, and that was the only upside to those visits.

Auntie maintained that she would like to have her old mother and her crippled sister live with her but it was impossible because our flat was just too small. And she had to keep her eye on me while I was studying. It wasn’t true. I have no doubt she preferred to share the flat with her favorite nephew than with her half-dead mother and blockhead sister. I was the only person Auntie truly loved. She liked it when I whistled during my morning shave in the bathroom, or polished off her scrambled eggs with gusto. She knew I had to finish my studies and she spared no effort making sure I did. However, there was a limit to how much effort she could spare, and that limit was not far off.

Auntie had reached the point when she needed quiet recuperation before the terminal advance of old age. And yet still she worked like a horse. She carried big packs of merchandise, went on business trips, often sleeping on the train. She paid for it with her heart, her liver, varicose veins. She was trying to cure them, visiting doctors and following their orders. But often life made this impractical. So Auntie suffered on, now and again letting out with a groan or a sigh, and who knows — perhaps that was the cause of the whole affair. Normally she bore her illnesses and old age with gallant heroism. She took care of herself, was not above a discreet touch of makeup and generally kept her spirits up, waking me up almost every morning with a joke. Truly, when I look back at those times, I have to admit she was indeed a very, very good woman.

Certainly, the cause of this whole situation could not lay in the small misunderstandings that naturally took place between us. In fact, if I remember correctly, no such incidents occurred that day. It was March, the frost still held fast. Auntie had to breathe on the windowpane to check the temperature on the outside thermometer. It was about ten o’clock. The snow glistened on the metal windowsill. But inside the room it was actually warm. I remember that when I was putting my slippers on, Auntie made some chirpy remark, which irritated me. Without hurrying things, I put on my trousers, a shirt and a sweater. I ate my breakfast of scrambled eggs, bread and tea with appetite. Auntie asked me what time my lectures began, to which I replied that they started at ten and therefore I had plenty of time. After breakfast Auntie asked me to hammer a nail into the wall so she could hang a mirror. This new task gave me a certain satisfaction. The hammer especially proved to be an oddly pleasant tool to handle, something I had not paid any attention to before. When the nail was hammered in, and I sat sprawling lazily on the stool, I was still holding the hammer in my hands. I was playing with it.

Auntie was getting ready to go out. She looked into the room, opened and closed the sideboard, checked the gas and bent down to pull on her boots. Then I walked up to her from behind and with all my strength I whacked her twice on the side of the head.

There was no doubt Auntie was a corpse. She lay still, a small trickle of blood pouring out of god knows where, as there was no visible wound. I grabbed her by the shoulders and turned her face up. No, there was no doubt – she was a corpse.

“Corpse,” I pronounced half out loud. “Corpse, corpse, corpse …” I sort of sang to myself, and felt uneasy.

Auntie’s eyes were opened wide; her moist teeth peered out from behind parted lips. And the blood – from her nose, mouth, ears – flowing in tiny rivulets into puddles on the floor. This fleshy, ripened body ceased to be fifty-four years old, ceased to feel pain, suffer illnesses, to enjoy itself. The shapely though overworked hands were now wooden. This body was so alien to me that I found it impossible at that moment to feel any pity or regret.

I became a little nauseous. I went back to my room and lay on the bed. I felt my hand sticking to the sheets. It turned out that both hands had blood on them; god knows how it happened, as there wasn’t really that much blood, and I hadn’t been touching it. So I went to the bathroom. It angered me to see I was leaving bloody marks on the tap. It struck me as too literary. Washing my hands, all the time I felt in my stomach and in my throat the morning’s breakfast: sweet tea and peppery scrambled eggs. And before me – Auntie’s corpse. I bent over the toilet bowl, pushed two fingers down my throat and vomited. After I threw it all up, once more I thoroughly washed my hands, rinsed my mouth and drank some water. Then carefully examined my face in the mirror.

I looked bad, but that could be put down to vomiting. At any rate, I saw in myself nothing of a murderer. I still had the same lock of hair on my forehead, lips, nose and the gray good-natured eyes of a luckless boy who at twenty-one was still just an awkward teenager. I took out a cigarette and smoking, walked to the kitchen, where I sat over Auntie’s corpse. As I smoked the fear began to rise. It was making me sweat. I was cold and nauseated. My fingers, by now burned by the cigarette, seemed so weak and helpless I could hardly believe what they had been capable of.

And yet they were capable. I felt pride, which alas was immediately soured by icy, slimy fear. It seemed there was nothing left for me but to go down and make a report at the police station, or simply stop the first policeman in the street and bring him in here. The policeman: red face of the common man, matter-of-fact, unbelieving tone – I was gripped by spasms of terror. I dragged myself back to bed and tried to calm down. I was talking to myself in a half-voice, as any fully spoken sentence would have been drowned out by the pounding fear.

“Calm down, my boy, calm down … Everything will be all right. We’ll manage … Ha ha, we will …” Something broke loose inside me. “Never mind, it’s nothing. I know it sounds paradoxical. Never mind, it’s nothing. You’ll live … We’ll get out of it … Remember,” I raised my finger, “you’re twenty-one years old. You have to live. Your whole life is ahead of you. Women, travel, work, adventures. You are twenty-one years old. Twenty-one. You are young, young …”

I was telling myself this and believed it all, though I did not at all feel twenty-one years old, let alone that it was a good reason I should live, and pleasantly at that. This does not mean I felt physically weak. I could have gotten up and lifted that heavy chair off the floor with my left hand. But why? What for? Don’t move, calm down.

I looked at my watch. It was ten o’clock. I still could make it to the lecture. The thought of getting out of the flat filled me with energy. I put my boots on, but as soon as I laced them up I changed my mind. This special day called for some little celebration. Devil knows why I thought that by turning up at the lecture I might be tempting fate. I unlaced my old skiing boots, took them off and put on my slippers again. I carried out these small tasks with precision and diligence. I was terrified but my movements were calm now. I began to consider ways of disposing of the corpse. It seemed child’s play. I’d chop the body up, flush some parts down the loo, burn some, take others away in parcels and throw them in the river or bury them. Bury them where? Ah, it’s a trifle. I know a quiet place in the woods on the outskirts of town.

I felt light-headed and carefree. I decided to carry out the plan without further ado. I went into the kitchen with an open penknife. I started with a finger. It turned out to be not that simple. The blade was blunt, the flesh gave in with difficulty, chafing and tearing. The bone just would not cut. I put away the penknife and fetched an axe. I swung it and the finger sprang off. Meanwhile, the tip of the thumb struck me in the eye. I picked up the finger and dropped it down the toilet bowl. It floated in the yellowish water like a pale sausage. I flushed the loo. The water gushed, snatched the finger and sucked it into the black void, but after a while the finger floated back to the surface. I yanked the chain. The pipes rumbled deeply, the water rose and filled the bowl. The finger disappeared. I took a piss. The finger resurfaced. The water subsided slowly. I fished out the wet finger and held it hopelessly between my own two fingers.

Apparently, that was not the way. It became clear to me that disposing of this hefty, one hundred and fifty pound body, depriving it of its full, overripe figure and its bale of fresh skin was not going to be as easy as it seemed to me, fed on the literature from the “time of contempt.” The corpse defended its individuality, its natural right to biological decay. Somewhat embarrassed, I returned to the kitchen and laid the hacked-off finger on Auntie’s breast.

There was something of a gesture of reconciliation in that.