Читать книгу Psychovertical - Andy Kirkpatrick - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

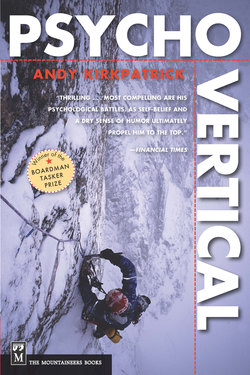

TWO Bird rock

ОглавлениеI was hanging in space, my fingers clamped tight, holding on, above a new and startling world of light and sound. People often ask me how long I’ve been climbing and I suppose it all began here. It was 1971 and I had just squeezed my way out of my mother.

The doctor held me above my mum, my tiny untested fingers wrapped around his and hanging on in terror, something that is often mistaken as strength.

‘My, Mrs. Kirkpatrick,’ said the doctor, dangling me before her like a zoo keeper dangles a baby chimpanzee in front of a TV crew. ‘You have got a very strong baby here. He’s as strong as an ox.’

My childhood was full of high places, of holding on, hanging, swinging, and falling, and so it’s no surprise that as an adult I would be drawn towards the heights and a life off the horizontal.

My first high place was a hill named Bird Rock, a mountain carved in half by some geological fluke, exposing a limestone face set in a valley not far from our house, and visible from our tiny garden. It always seemed strange and exotic, always there on the horizon, mysterious, its summit seemingly inaccessible amongst the more pedestrian rolling green hills that surrounded the Welsh village where I grew up. I’d seen films like King Kong, Tarzan and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, where strange rock faces yielded prehistoric lands and lost species. I wondered if Bird Rock was the same, its craggy face perhaps hiding dodos, pterodactyls and giant eagles that would have to be fought off.

I was five and it was my first mountain, and my dad always promised that when I was a little older we would climb it together.

My father was a mountaineering instructor in the RAF, based at a Joint Services camp in the Welsh seaside town of Tywyn, running courses for the army, navy and air force. That is the perfect job for a sadist: running poor recruits around the hills in the rain, making them shimmy across greasy ropes above ponds of vile green liquid, pushing them to near hypothermic death in foaming rivers, all in the name of training. My dad threw himself into the job with gusto, thinking up increasingly devious ways of scaring and stretching recruits in the outdoors, always setting an example by going first. I can still remember creeping into my parents’ warm bed on dark winter mornings, as my dad got up to take a load of recruits down to the sea for an early morning swim, his face grinning with the craziness of it all. You could say he was very pre-health-and-safety.

He was pretty unconventional for someone in the RAF in the 1970s. Rather scruffy and prone to bend the rules, he never went too far in his long career, generally being placed out of harm’s way in the outer reaches of the RAF: mountain rescue teams, officer development, and outdoor education. His only advice to me growing up, apart from how to tie knots, roll kayaks or light a stove, was ‘Only work hard when people are looking.’ No doubt this tongue-in-cheek approach didn’t serve him well when it came to making air chief marshal, but fundamentally all he wanted to do was to go climbing.

He was charismatic, a fantastic story teller and a great ‘people person’, which is probably why they didn’t just boot him out. These skills trumped a pair of well-ironed trousers or polished shoes any time. His enthusiasm for the mountains was also infectious, whether you liked it or not. He pursued climbing and adventure with a passion, and at that time the only way to do this was to work as an instructor in the forces, where you could use the system to go away on trips you would never have been able to afford otherwise. Throughout those early years there were big gaps when my dad was away on courses or expeditions, but I never stopped idolising him, and still remember my heart leaping when, sitting on our back fence, I saw him for the first time in weeks, coming out of the base and across the playing field to our house. Coming home.

He applied many of his military training techniques to my upbringing, such as exposing people to danger in a controlled environment, so as to better prepare them for real danger in the future: war in Europe, global Armageddon, primary school. My mother still tells the story of her coming home to our flat when we were posted to Sardinia, and finding him watching the TV, while I sat in my nappy in the kitchen playing with the largest carving knife in the cutlery drawer. I was two at the time. On being challenged by my mum, my dad’s only response was, ‘You have to cut the apron strings some time.’

Very often in my childhood, while I was standing on a tiny ledge, walking across a plank above a big drop, or about to jump into an icy lake, my dad would shout, ‘A real man would do it,’ to which I would always reply, ‘But I’m not a man, Dad.’

The closest this exposure came to unravelling was one Christmas afternoon, when he took me down to the sea for a walk as a huge winter storm raged, and surf crashed over the sea defences. The most hazardous spot was the boat ramp that led into the sea, the waves rushing up it and fanning out behind the sea wall. Dressed in my black donkey jacket and red wellies, I ran backwards and forwards, trying to race the waves down and back again without getting too wet, when all of a sudden a huge wave overtook me, knocking me over and sucking me back into the sea.

Luckily my dad was close by, and was used to swimming in the cold Irish Sea. He dived in and managed to pull me back to shore. I was frozen, my eyes were full of sand, but I was alive. My strongest memory is of being run home in his arms and then plonked in a warm bath, the remaining contents of a bottle of Matey bubble bath being added to the water as a treat. I suppose it was an early lesson that when you survive a life-threatening trauma, people tend to treat you nicely.

My dad had joined the air force at seventeen. It’s strange he found himself having a role in the mountains, since he was born in Hull, one of the flattest places in Britain. I often wonder if having an adventurous spirit is genetic, as my dad’s father and grandfather had also been in the military, his dad fighting in Egypt and in Ireland during its civil war. It’s hard to imagine now how limited people’s lives and careers were back then, born and dying in the same town, taking up the trade of their fathers. For most, joining the navy or army was the only way to break free.

My dad’s two brothers were also rather unconventional. Eddy Kirkpatrick had been a salvage diver whose hair-raising adventures deserved their own book: diving on sunken German U-boats in primitive gear for their brass torpedoes, and searching for Nazi gold lost in the North Sea. His life must have been lived by the seat of his pants. Doug Kirkpatrick had worked on Baffin Island in the Arctic as a radio operator, and later as a hunter in New Zealand, before he settled down to normal life as an insurance salesman.

Maybe this wanderlust comes from the place where you are born. The fictional adventure of Robinson Crusoe had begun in the port of Hull and I wonder if maybe this spirit for adventure was part of the genetic heritage of the city. It is a place from where boats sailed all over the world, where seamen once signed on for white-knuckle rides to hunt whales in Greenland, and to fish on the violent northern oceans, a city whose heart was laid waste by the cod wars. Whatever the reasons, the Kirkpatricks are a strange breed, a mixture of many roaming people, Russian, Scottish, Romany. Whoever they were, they all seemed to be afflicted with wanderlust, and were single minded and incredibly stubborn.

Since I had been born we had moved around the country several times, and a lot of my early memories involve playing in wooden RAF-issue packing cases. However, my dad’s posting in Tywyn was long enough for it to become the place I see as my first home, and I can think of no better place to grow up. It was nestled between mountains and ocean, and we lived next to the camp. The military and mountaineering seem to produce larger than life characters, men who jumped straight from the war films on the telly, and many of them made an impression on me. Our next-door neighbour was a man called John Bull, who seemed to be able to communicate only by shouting. He was in the army and was a lifer like my dad. He was a fellow instructor and would always be thinking of new ways to torture the recruits. In his house he had a full-size Greenlandic kayak he’d brought back from an expedition.

On Sundays we would go to the sergeants’ mess for lunch, where there were pictures of mountains, and walls full of plaques, polished ice axes and mountaineering mementos. On one wall was a giant picture of Mount Everest, with its camps marked, part of an upcoming military expedition. Standing there in my best clothes, I felt I was in a special place, a place of men. Even to a five-year-old, there was such a feeling of being wrapped up in the military, of being one institutional family. I can understand how soldiers can carry on fighting in wars that they feel are unjust, or illegal. It was a home.

I was a very physical child who was always running, climbing and generally getting into the type of trouble that such kids usually do. My clothes were always a collection of patches, ripped, scuffed, torn and then mended, with shoes lasting me no more than a few weeks, meaning cheap rubber wellies and shorts became the only answer for my despairing mum. My legs were always brown with bruises, and scabby. The arrival of my brother Robin had given me another person to play with, but, because I was a rough child, Robin would often come off worse: falling off, falling down, being hit, knocked out or generally injured in any playtime we had. One of my strongest memories is of my mum slapping me, my brother standing crying behind her, while she shouted, ‘Your brother must have rubber bones.’ It was a phrase repeated so often I actually believed such a thing was possible, no doubt further adding to Robin’s misery. I used to think that our family were borderline freaks, as not only did my brother have rubber bones but my mum also had ‘eyes in the back of her head’.

Other children were not fortunate enough to have rubber bones, and for a while I was in big trouble after pushing a twelve-year-old girl off the top of the slide and breaking her arm. I wasn’t a bad child or a bully in any way, only a child who ‘always took things too far’.

I was a very happy-go-lucky boy, but Robin was less easy to please. My mum would often tell him to stop whining, sometimes slapping him on the legs and telling him ‘Now you have something to whine about.’ She often put the disparity in our characters down to the fact that the doctor had run him under the cold tap as soon as he’d been born, a shock he’d never quite recovered from.

My mum had met my dad at a dance, and they were married not long afterwards. She was also from Hull. She had wanted to go to art school, but instead had been forced to give up such fancy notions and work in a bakery. I suspect this had had a major effect on the rest of her life, as she would often tell us this story, wanting us never to compromise what we wanted to do. My mum was far from pushy, but she always told us that the world was our oyster—not that I ever really understood what that meant.

What she wanted most of all, though, was children, and I had been her firstborn, in 1971, Robin coming along a year later. Times were hard for her, with my dad’s pay low, and she would often repeat the phrase, ‘I don’t know how we’ll make ends meet’, which I mistook as ‘hen’s meat’, often wondering if hen’s meat tasted just like chicken. Although we were poor, my mum hid it well, and did things that were free: going for walks, playing on the beach, drawing and painting, and giving the priceless gift of a parent’s attention. My mother’s side of the family had been craftsmen, her father a carpenter, his father a head gardener, her great-grandfather a stone mason. From her I learnt to draw, something that would prove invaluable later in life. I scribbled on anything at hand as soon as I could hold a crayon.

Like my dad, my mum wanted fun and adventure, and a life less ordinary than the one she had left behind in Hull, but not at the cost of security for her and her kids.

We lived on the military estate on the edge of the camp, not far from the beach. Even at the age of five I was a bit of a loner and a daydreamer, happy to be by myself, playing for hours in the garden, making up imaginary worlds. I was lucky enough to have the freedom to do my own thing and wander around the estate by myself, in the days before people even knew anything about pedophiles, where there were only ‘funny men’. I was only reined in after I went missing one day and didn’t come home for lunch, and the whole camp was mobilized to look for me. Several hundred soldiers and airmen combed the sea shore, fields and rivers looking for my body. In the end I turned up asleep in a collection of hay bales a few hundred metres from our house. My mum belted me with relief, shouting, ‘I was worried sick,’ a phrase that was now added to her daily litany.

After that I had to stay with Robin, although this almost cost him his life on more than a few occasions.

My worst youthful scrape, and one of my earliest fully formed memories, was going to our next-door neighbour’s house with Robin to look at their aquarium. It stood on a wooden stand near the front door, looking like an enormous TV filled with fish. We would stand with our noses pressed up against the glass, and watch the fish race around. On this day, my mum stood talking on the doorstep to the couple who owned the fish, my dad being away on an expedition. She had probably taken us around to see the fish as a distraction because I was missing him.

We were playing our usual fish-spotting game, eyes tracking the red, blue and purple flashes darting around the tank. The couple who owned the house would always tell us that we had to be careful as the tank held piranhas, and that they would bite us if we got too close. I always wondered if they really would. If I were to stick in my hand, would the flesh be ripped off it in seconds like I’d seen in an old film once on our black and white TV?

I wanted to find out if it was true.

The fish darted away from the glass as I moved round to the side of the tank, trying to grab the top so I could pull myself up and dip my hand in. I would probably have lifted Robin up so he could dip his hand in, but already he had learned not to get involved in any of my games and would probably have started crying.

Being small for my age I found the tank was too high, so, looking for another option, I saw that I could maybe climb up between the wall and the tank, using the skirting board as a foothold. I started by squeezing my leg in, my welly sticking well to the edge of the skirting as I tried to squirm up the gap, which widened as I pushed in.

I looked through the glass as I moved up, seeing through the drifting green murk my brother’s tiny face, his eyes fixed on the dancing fish. I pushed up. I slipped back. I pushed harder.

The tank moved . . . then moved some more . . . then crashed over onto Robin. An explosion of glass and water shot through the porch, a tsunami raging out of the front door and knocking everyone off their feet.

There I stood, my back to the wall, looking down at the floor littered with glass, pebbles, soggy green plants, twitching fish and, right in the middle, the tips of two small red willies—my little brother.

Incredibly Robin made a swift recovery, and after a night in the hospital he left with only a few cuts, being declared by the doctor as having a very strong heart.

Personally, I put it down to his rubber bones.

Not long afterwards my sister was born. My mum had always wanted a daughter, and had become so desperate she’d taken to clothing Robin in dresses when he was a baby. Joanne was born in 1976 and from the beginning everything changed.

She never stopped crying, screaming non-stop for six months. The calm, fun house I’d known existed no longer. Mum and Dad became steadily worn down, tired and strung out. My dad could escape but not my mum.

Then one day my mum took us all to the hospital, and I can remember me and Robin waiting in the hallway while she talked to the doctor. Then I could hear her crying and screaming, appearing in the hallway distraught. They had asked her if either I or Robin had dropped Joanne. It appeared her hip was broken. Soon, though, it was discovered she had been born with an undiagnosed congenital hip defect, meaning she had no hip bone, and had been in terrible pain since her birth.

Soon after that, Dad was posted to another camp in Llanwrst on the edge of Snowdonia and a few weeks later we followed him, Joanne’s tiny body encased in plaster. We were leaving the happiest period of my childhood behind.

Everything was different; new school, new house, new friends and, worse still, new parents. I hated school. I felt like an outsider, starting from scratch. I was no longer at the center of my parents’ universe: Joanne took up much of my mum’s time, while my dad seemed to be away more and more. When he was around he seemed bad tempered, or not really there at all. He was about to go on a trip to Yosemite, a name I only understood from Yosemite Sam on the TV, and this further added to the stress, leaving my mum with me and Robin, both unsettled, and Joanne. I suspect that the pressure was too much for my dad: his happy and conventional life, a life where he could have the freedom to climb and still have a family, began to collapse. Demands began to be made of him. He was forced to choose.

One night, Robin and I woke up and could hear noises downstairs. We crept down to the dining room where our mother was at the table with our dad. She was crying. There had never been crying before we moved from Tywyn, but now it seemed to be happening all the time. We had always been happy; we had never had much but at least we had that; there had never been room for sadness. This was all to change. He was telling her something. Something she was shocked to hear. Her world and future falling apart. Her heart broken. Another woman.

The following morning we were bundled out of bed by Mum, quickly dressed, and walked down to the train station. It was early; a fog obscured the line. I wondered if this meant I didn’t have to go to school. My mum wasn’t talking. It took all her strength just to keep it together.

The train appeared out of the mist and slowed to a stop.

We stood, no longer the family we had once been, our bags all packed for a new life in Hull, a place far removed from my world of sand dunes and hills, from beaches and green fields full of sheep, and from my dad. I had no idea where we were going, or that we would never come back—that Dad and I would never climb Bird Rock together.