Читать книгу For Alison - Andy Parker - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеAlison

It was Monday, August 19, 1991, and the world was on edge. Communists from the old Soviet regime had orchestrated a coup against Boris Yeltsin and his fledgling democracy. If it succeeded, no one knew what the implications were for our country, but the prospects weren’t promising.

Barbara was in labor with our daughter, Alison, and we watched the live CNN broadcast on the overhead television at Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis, Maryland. It was a nice but unremarkable facility, made to feel as homey as possible while still being sterile. All hospitals look pretty much the same.

We were both shocked by the unfolding world events, but we had other things on our minds. Just great, I thought. We’re bringing a child into a very uncertain world. The excitement of Alison’s imminent arrival was tempered by what appeared to be a world on the brink of war.

Adding to my concern was the health of the coming child. A few months before, our first-born, three-year-old Drew, had been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome. At that time, little was known about it; doctors knew it was somewhere on the autism spectrum, but it mostly remained a mystery. Now my wife was giving birth at age forty-one, an age where all kinds of problems can occur. The obstetrician who was supposed to deliver Alison was not on duty, so another from the practice was there instead. We had never met him previously, but this fortyish mustachioed doctor bore an uncanny resemblance to Barbara’s brother-in-law, and thankfully he had a good sense of humor. His joking demeanor helped take our minds off the ominous events that were unfolding, but only a little.

Barbara’s first delivery with Drew was via emergency C-section; I hated that I couldn’t be in the room when he arrived. Sometimes after a C-section doctors discourage natural childbirth, but Barbara’s doctor saw no reason for this. This time everything was going smoothly, except there was one spot on her abdomen that the epidural did not seem to help. Barbara was not thrilled by this development. Barbara’s not exactly the natural childbirth/midwife/delivery in a kiddie pool type, so she was ready for Alison to make her debut as quickly as possible.

Fortunately, Alison cooperated, Barbara pushed like a champ, and before long, I saw my daughter emerge into the world.

There are no words to describe what it’s like to witness the birth of your child. It’s a wonder, a miracle, but even that doesn’t go far enough. As with parents since the beginning of time, emotions ran the gamut from relief to joy and ultimately profound love for this life we had created.

At that moment, we didn’t care about the rest of the world or what it would turn into. I just knew we had something special from the moment I laid eyes on her. Two days later, we were all home, the Russian Federation survived, and I knew the light that had come into the world on such a dark day was destined for great things.

•

I want to tell you what Alison was like. This is no easy task.

Imagine your own child, or if you don’t have a child, imagine your wife, or your husband, or your mother or father. Now imagine describing that person—capturing everything that makes them special with crystal detail—in a single chapter of a few thousand words. Even if this entire book was solely devoted to describing how wonderful, unique, and talented Alison was, it would still fall short.

But my hope is that if I share a few stories—the little moments over the years that stick out—you’ll get a glimpse, and hopefully that glimpse will be enough.

The first thing I’ll tell you is that Alison was an easy baby. She was perfectly healthy, she slept through the night, and she was never colicky. About the only thing you could remotely call an issue was that she took a little while to get the hang of potty training, but once she mastered it, boy was she proud of herself.

On her first Halloween outing, Drew dressed as radio legend Dr. Demento and Alison dressed as a fairy princess, complete with a purple gown, a sparkling tiara, rosy cheeks, and a candy bucket that Barbara fashioned into the perfect gaudy accessory using tin foil and purple ribbon. I escorted them as they went door to door. We lived in a newly built subdivision in Bowie, Maryland, with lots of kids, nice sidewalks, and houses that were as close together as houses in new subdivisions tend to be. I would hang back on the sidewalk in front of each house while Drew took Alison’s hand and escorted her to each front door.

Alison was a little over two years old at the time. I’m not sure the concept of Halloween registered with her as much as the excitement of it all. It’s like the kids whose parents take them to Disney World at that age. They enjoy that excitement, but it doesn’t have much more impact than going to the local Chuck E. Cheese’s.

In Alison’s case, it presented an opportunity to turn on the charm and engage the public. As I waited for them to trick or treat, to get their candy and return to meet me at the sidewalk, I began to notice a pattern. I was too far away to hear what was being said, but I saw parents in their doorways laugh, say something, and put more candy in Alison’s sparkly princess bucket. This went on door after door, so I finally walked up behind them to get within earshot.

Then I heard what prompted the neighbors’ responses. In unison, the kids would say “Trick or treat!” But then Alison would proudly proclaim, “I poo-poo in the potty!” to which the reaction was, “Well, that’s very, very good. I’m going to give you some extra candy for that.”

It was clear she understood marketing at an early age.

Middle and high school were an awkward time for Alison, though I suppose it’s an awkward time for all of us. But in the days when girls go through puberty at a sometimes alarmingly early rate, Alison was the opposite. Barbara and I were late bloomers, and Alison was no different. It didn’t help that, because her birthday was in August, she was effectively a year younger than many of her peers.

Middle school can be particularly rough on kids like Alison. Barbara had been relentless with her about skin damage from the sun, so her skin was snow white, and while it would give her a luminescence as a young woman, it was a subject of mockery among some of the crueler middle school boys. They nicknamed her “Casper,” as in the ghost. She was a gawky little kid with too many teeth surrounded by boys and girls who were physically mature if not emotionally so.

As she entered high school, she was not cheerleader material, and most of those girls and boys just ignored her. She wasn’t cool enough for them. It must’ve hurt in some ways, but Alison never seemed to let it get to her.

She embraced being a nerd through high school as she started to transform from the ugly duckling into the beautiful swan. She was proud to be a part of the Piedmont Governor’s School’s award-winning robotics team called the STAGS, and she put all of her other energy into academics, swim team, and dance classes. She also had rock-solid stability at home, and while many of the “cool” kids were out getting drunk, she spent her free time with a few good friends or with family. Her only dates in high school were to proms. It didn’t bother her. And as so often happens, while many of those kids reached the zenith of their lives waving pompoms or playing football, Alison kept on going and didn’t look back. Funny how just a few years later when she became a television personality, many of those kids wanted to be Alison’s friend.

Summers were spent on our boat at Smith Mountain Lake, a place we all loved. It’s a vicious irony to have such wonderful memories of a place and yet never be able to return.

Alison had a knack for doing a remarkable job at everything she tackled. She worked hard on academics, but athletics seemed to come naturally. During those Casper years, she won the respect of her peers by being down-to-earth, and also by demonstrating her athletic ability.

It all coalesced one field day. The sprinting competition was the main event. As Alison would laughingly tell the story, “As I was racing in my heat, I could hear one black classmate shrieking at the top of her lungs, ‘Run little white girl, run!’” She led the field.

Her classmates respected her ability, and it was an example of Alison’s underlying fierce competitiveness. Alison wasn’t content to just compete at anything. Her goal was to win at everything. And she practically did, with extraordinary composure.

Barbara and I put Alison in gymnastics when she was around seven years old. After a couple of years of learning various skills, she was ready for her first competition. Like any sports dad, I vividly recall the first routine she did at her meet. It was the floor routine, and while my heart was pounding with excitement, she coolly nailed it. On the balance beam and vault she was fearless. I can’t remember now how the meet turned out, but I know she placed in her very first event.

Through sixth grade, she competed around the state and took home her fair share of medals. All the while, she was taking dance classes, which she’d started when she was four years old. The wear and tear on her knees was taking its toll, so she decided to give up gymnastics and concentrate on dance. By then, she was also hitting her growth spurt. It’s rare to see a 5´9˝ gymnast, and it was clear that was the direction she was heading in.

Alison excelled in dance just as much as she excelled in gymnastics. At her dance studio’s year-end recital, she performed the role of Dewdrop in Waltz of the Flowers. I will never forget it, just as I’ll never forget the tears of pride that streamed down my face as I watched her. She was in sixth grade, the youngest dancer in the class to dance en pointe. Those strong gymnast ankles made all the difference. She was the graceful little angel upstage in the spotlight while all the older girls were downstage. She glided gracefully, effortlessly executing pirouettes. At the end of the performance, the crowd went nuts and I went to pieces. My heart was bursting with pride, but Alison was cool as a cucumber.

By the time Alison was a junior in high school, I was sure she had the talent and the looks to go to Broadway. That opinion wasn’t just subjective. I had performed on Broadway in a past life and I knew what talent looks like. The mark of a great performer is performing effortlessly. She was fluid and graceful and she danced that way through high school. I’ll always wonder what it would have been like to watch her in New York.

As a junior, Alison decided to try out for the swim team. She had reached her full height, and her strong dancer’s body also turned out to be perfect for swimming. She was a competitive swimmer during her last two years of high school, swimming freestyle, medley, and her specialty, the butterfly. She won each event in every local meet. Some girls on the swim team were in it for the social aspect and merely wanted to participate; Alison wanted to beat every one of them—and she did. She received the Piedmont District Swimmer of the Year Award both her junior and senior years.

In cities the size of Richmond, Virginia, high school swimmers were in the pool practicing twenty hours a week, but our much-smaller hometown of Martinsville, about three hours west, didn’t afford that opportunity. They could only practice at the YMCA for about six hours a week. As a result, when Alison competed regionally, she didn’t win, but she was able to qualify for the state meet her junior and senior years. She did it on sheer ability. Had she been part of the team that produced our good friend Lori Haas’s son Townley, I have no doubt she could have gone on to win an Olympic gold like him.

Soon enough, we discovered the wonders of white-water paddling, first on guided rafting trips on the New and Gauley Rivers. By the time we graduated to kayaking, Alison was intuitive and fearless on the water. Our first guide told us, “When you get to that big rapid, keep paddling. Don’t stop or you’ll get pulled back into the hole.”

“Keep paddling” became our family slogan, though we didn’t know at the time how much it would one day mean to us.

While Alison had a talent for nearly everything she touched, she didn’t let it inflate her ego. She never lost the ability to laugh at herself. There was one story in particular that followed her for her whole life.

It began back in 1994 when we had had enough of Maryland’s cold weather and high taxes. We sold the house, stored the furniture, and drove to Texas to spend Christmas with family. I had sold my golf shirt business and was about to start a new job as a partner in a new endeavor, but it fell through the day after Christmas. I had to get another job fast, and I ended up taking one with Cross Creek Apparel in Mount Airy, North Carolina. They also made golf shirts, and the president of Cross Creek liked my creativity and offered me a job to make licensed PGA Tour merchandise.

We were in Mount Airy for a year and then I was transferred to Columbus, Georgia, where they housed all their licensing projects. It was a miserable time for me and Barbara. The brutal heat and humidity in Georgia made us miss Mount Airy more than we did already, but Drew and Alison were quite resilient. They adapted well, and we did everything together. We were fortunate that our best friends just happened to be each other.

In Columbus, Alison was in kindergarten at Reese Road Elementary School. One day her teacher was reading a story to the class. All the students sat on the floor in a semicircle in front of her. What follows is an account in Alison’s own words.

“When I was five years old, I started kindergarten at Reese Road School. My teacher Mrs. Enmond was full of encouragement and entertainment, and my classmates and I really enjoyed her class because she was kind, caring, and willing to help us whenever we needed her. Because she was so wonderful, we all wished she was our mother! On the day I discovered her flaw, I also learned an important lesson about myself.

“On that infamous day, Mrs. Enmond and the class were sitting in a circle for story time. Because she was reading [a story about] Marshmallow the bunny, I was in the front listening attentively to my favorite story. Suddenly, complete chaos invaded this peaceful story time, and everyone was shrieking and running around the room! Confused, I approached my friend Victoria and shouted, ‘What’s going on?’ She exclaimed frantically, ‘There’s a cockroach on the floor!’ At that very moment, I felt tiny little legs crawling up my arm and into my dress. I scrambled to find Mrs. Enmond, who was just as frenzied as the rest of us. ‘Mrs. Enmond! I think there is a cockroach in my dress!’ I screamed. She took one look at me, leaped onto her desk, and waved her arms in the air, screeching, ‘I can’t help you!’ Because all of my classmates realized that the cockroach was not chasing them, but rather crawling on me, they all giggled while I just stood there. Finally, the teacher’s aide grabbed me and shook my dress vigorously until the cockroach fell onto the floor. Calmly, she retrieved the fly swatter and flattened the bug.”

Alison was embarrassed by the cockroach story, but as she demonstrated through her developing skills, a story like this could be helpful in learning how to find humor in situations. It could connect with an audience.

The cockroach story resurfaced five years later at a 4-H speech competition when Alison was in fifth grade. By that time, we had moved to Martinsville where I had a new job with Tultex Corporation. We didn’t know it then, but Southside Virginia would become our permanent home.

The same confidence Alison had shown in her endeavors since the age of two was apparent in her speech competitions. She won the local competition and advanced to the district level. Some years later, she wrote about her 4-H experience:

“As embarrassing as the [cockroach] story may sound, I learned something from this and have been able to use it to my advantage. For example, I competed in the 4-H Public Speaking Competition. My classmates decided to write about cliché topics like ‘the most influential person they know,’ or ‘what integrity meant to them.’ This was the time for me to test the usefulness of this embarrassment. When I stood before my first audience and delivered this speech, people had puzzled looks on their faces. No audience member had ever heard something so ‘unique.’ I received my scorecard and had advanced to the next level! Finally, after a series of competitions, I reached the state level competition. I was extremely nervous because all of the other competitors had very intelligent speeches about the economy, social issues, and other serious matters that were over my head. Standing at the podium I took a deep breath and gave my speech. I won.”

She wasn’t through with the cockroach story. When Alison applied for early decision to James Madison University, she decided to use that story in her personal statement. The last paragraph sealed the deal:

“Having that ability to laugh at myself will benefit me. Who would have thought that a cockroach crawling up my dress in kindergarten earned me the 4-H Public Speaking trophy in my living room? Because I did not let my embarrassment overwhelm me, I was able to accomplish my goal. More importantly, learning to appreciate instances like this has helped me find humor in even the most unusual circumstances.”

Later in Alison’s high school career, she attended one of the best-kept secrets in Martinsville/Henry County: the Piedmont Governor’s School for Mathematics, Science, and Technology. Rising high school juniors must apply to be accepted into the program, and if they’re chosen, they begin the school day an hour before their peers. When Alison was in the program from 2007 through 2009, it was held in an old elementary school building in town. Before returning to their regularly scheduled high school programming at noon, she and her Governor’s School classmates spent their mornings challenged with a college-level curriculum that helped turn them into creative thinkers.

Alison loved the demands placed on her, the inventive projects she completed, the teamwork the program fostered. Like many of the other successful students in the program, she graduated from high school with an associate’s degree from our local community college without actually attending classes on the campus. It worked out to roughly sixty hours of transferable hours to James Madison University. She made good use of those hours, too. When she told me the courses she was taking her first year at JMU, most of which sounded like Underwater Basket Weaving 101, I asked her why she was bothering to take all that fluff. I’d placed out of some courses back when I went to college at the University of Texas, but I still had to bust my hump taking tough freshman classes.

“Scooter,” I asked her, “aren’t you supposed to be taking a serious course load?”

“Dad, I got all that stuff out of the way at Governor’s School. I have to get through my GMAD [General Education Media Arts] classes and be accepted to SMAD [School of Media Arts and Design] and then I can’t take the other courses until I’m a junior.”

“Uh, okay.” She knew what she was doing, even if dear old dad did not.

During her entire first year of college, she mostly took electives. One of those electives was calculus. Most students wouldn’t volunteer to take calculus even under penalty of torture, particularly if it wasn’t their major, but Alison loved math, and she had already become an old hand at calculus during her stint at Governor’s School. She aced every test.

One day, her professor took her aside and asked her, “Why are you in this class?” Alison told him she simply liked math and thought it would be a fun elective.

The following semester, the professor hired her as a tutor.

Governor’s School is where Alison caught the journalism bug, which is the reason she chose JMU. Being on the Governor’s School yearbook staff planted that seed, but a high school band trip to Atlanta (she played trumpet and French horn) made it sprout and grow.

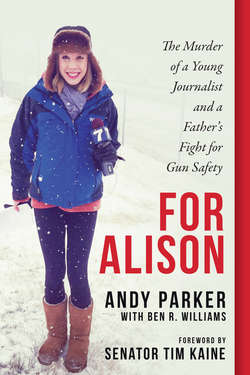

During the band trip, Alison and her classmates had the opportunity to tour CNN. She was in awe. She had enjoyed the band trip to Disney World the previous year, but in her eyes, Disney had nothing on CNN. She saw her future in those halls. There is a picture of her beaming in front of the giant CNN block logo, arms outstretched over her head, palms out in a display that suggested, “This is where I’ll be one day.”

And she did appear on CNN, just a few years later. We’ll return to that soon enough.

Once she knew that journalism was her calling, it was simply a matter of choosing a college. Barbara and I limited the search to Virginia schools to take advantage of in-state tuition, so there were only two schools that she ever really considered: James Madison University and the University of Virginia. When she discovered that UVA didn’t have a journalism department, she didn’t even bother to apply.

Alison sailed through her first two years at JMU before diving headfirst into her journalism courses. She honed her skills as a storyteller and soon became the news editor for the Breeze, JMU’s award-winning student paper. She enjoyed mentoring her fellow students, and she liked writing so much that she nearly decided that was her calling. But that was before she took any on-air courses.

When she started in video production, it became clear to her professors that she had “it.” Her beloved Professor Ryan Parkhurst, a trusted mentor even after she graduated, said, “I’ve never had a student with the talent, drive, and gift that Alison possessed.”

I only saw one video of her from JMU. She was in the field, and got the “toss” from her student anchors. It was decent, but it wasn’t prime time material. Hey, it was her first time, and she was still in school. Even in that brief clip, she did do something that was purely Alison; right before the live shot, a truck pulled up in the background, and she sprinted over to it in high heels to ask the driver to move out of the way, sprinting back just in time for the shot.

The next time I saw her on television, it was the real deal. It was the summer before her final semester at JMU, and she had an internship at WDBJ, a CBS-affiliated station in Roanoke.

“Scooter, are they going to let you go on-air?” I’d asked her.

“Oh Dad, they’re probably just gonna make me go get coffee.”

Clearly, she had no expectations. But the station did. They saw “it.” She called me after she’d been there about ten days, bursting with excitement.

“Dad, I’m doing a package!” she said. “It’s going to be on at the six! I just finished, and I think it’s going to be really good!”

“What’s a package?” I asked. “And what’s the six? Does that mean you’re going to be on TV?”

Indeed she was. In the months to come, she would playfully admonish me for confusing a “package” with a “stand up.” (In broadcasting vernacular, a “package” is a report in which the correspondent narrates around video and interview excerpts, while a “stand up” is when a correspondent stands at a news location and talks directly to camera, live or taped.)

Barbara and I watched WDBJ that evening, breathless. There was Alison, doing a story about a camp for diabetic kids. She looked great, professional, like a veteran correspondent. Our hearts were bursting with pride. Barbara and I couldn’t stop smiling, and we gave each other high-fives until our palms stung.

Proud Dad posted that clip on Facebook, and looking back, I think it was my all-time favorite. Watching our daughter take the first confident, practiced steps toward her dream was an experience like no other. I would give anything to relive it.

Alison went on to do five more packages until one of the reporters complained that an intern was doing all their work. I will always wonder if the complainer was the one who ended up killing her.

On her last day as an intern, we took a picture of her sitting at the anchor desk. Like the photo in front of CNN, it was another prescient “I’ll be here one day” moment.

As her final semester at JMU wound down, Alison used the video from WDBJ for an audition reel to send to prospective employers in the TV news field. She graduated in December, a semester early, with genuine professional experience and an impressive list of accomplishments, but she had sent out her audition reel in November. She had a few criteria: The station had to be a top 100 market, it couldn’t be anyplace cold, and it would preferably be close to home and/or family. She sent out just six packages. A couple of stations didn’t reply, a couple said they needed someone with more experience, and two wanted to talk.

One was a station in College Station, Texas. It was farther away from me and Barbara, but close enough to the rest of the family in Texas. She had a phone interview with the news director who promised a follow-up in a week or two.

The other that wanted to talk was WCTI in New Bern, North Carolina. It was a top 100 station, reasonably close, and in a great area. The news director, Scott Nichols, received Alison’s reel on a Tuesday and called her Friday. The interview went well. He asked her for references and said he’d be back in touch with her soon.

He called her references over the weekend and called her back on Monday, offering her a job as a reporter for the Greenville, North Carolina, viewing area. She would be working alongside another reporter, although that situation would change a week after she arrived.

After getting the news, she called me, breathless.

“Dad, he offered me the job! He even said I’d be making $24,000 a year!”

She had won the lottery.

“What did you tell him?” I asked.

“I said, ‘Don’t you need to see me in person?’ He said, ‘No, I see everything I need to see from your reel and your résumé. You don’t have to decide right away, you can think about it for a few days, but we really want you.’ I was so stunned I just said, ‘OK, let me think about it.’”

“How do you feel about it?” I asked.

“I like it,” she said.

“Then, Scooter, call him back and accept the job. It sounds like the perfect start for you.”

And so she did. Alison had a job in television two weeks before she got her diploma. She graduated on December 15, 2012, started with WCTI the day after Christmas, and was immediately thrown into trial by fire, doing a stand up her very first day. I’ve heard from pros in the business that what she pulled off rarely happens, if ever. But Scott Nichols saw “it.”

Scott wanted her to spend a month in New Bern learning the ropes at the station before heading to Greenville. The problem was, there was little to no temporary housing that she (or I) could really afford. I called around for her before finding a unique arrangement: she spent January in an assisted living community. She had a pretty nice apartment, and of course it was quiet. I joked with her that she should join the residents for dinner and enjoy those cooked-to-death green beans. She drew the line at that, but was grateful for a nice cheap place to live for a while.

Two weeks later, after several packages and stand ups, Scott said he wanted to meet with her.

“My original plan was to have you working alongside a reporter in Greenville,” he told her, “and you can still do that if you want. But after watching your work, I’ve got another opportunity I’d like you to consider. Our bureau reporter in Jacksonville is leaving. How would you like to run your own show there?”

Alison jumped at the chance. Now she was a twenty-two-year-old bureau chief with her own veteran cameraman working for the number one station in the market. She covered hard news, but in Jacksonville it generally revolved around these kinds of stories:

“Marine Comes Home to Hero’s Welcome,” or

“Marine Shakes Baby to Death,” or

“Big Meth Lab Bust.”

A year in, recognizing her ability, Scott gave her an opportunity to be the fill-in anchor. Barbara and I watched the first episode at home, watched her sitting at an anchor desk for the first time. We were giddy with joy, and it marked the moment that Alison knew she wanted to be a full-time anchor.

When the noon anchor position became available, Alison lobbied hard, but the job went to another deserving candidate. She was disappointed, and she knew her options were limited. The other anchors at the station had been there for a long time and had established roots in the community. They weren’t going anywhere. It was time to move up and move on.

As she was preparing her reel, Tim Saunders, a reporter from WDBJ, gave her a call. He said they had a couple of interesting prospects in the works and that Kelly Zuber, the news director, wanted to talk to her. Kelly told her they wanted to create a regional reporting position that was based in Martinsville. As always, Alison asked me what I thought.

“I could live at home and save a lot of money,” she said.

“Yeah, Scooter, you could. But as much as we’d love to have you back home, and even if they paid you more money, this would be a step back for you.”

Alison agreed. She thanked Kelly and declined the offer.

Kelly called her back a day later.

Melissa Gaona, the “Mornin’” reporter, had been promoted to anchor. Would Alison be interested in taking her old position? The job was mostly fluff reporting and spanned the station’s entire viewing radius. She would work five days a week alongside a cameraman named Adam Ward, and she would get a $9,000 a year raise, a wardrobe, and a makeup allowance. Alison had won the lottery again.

Barbara and I got up at the crack of dawn, quite literally, to watch Alison’s first “spot.” It featured a climbing wall, and as would regularly happen, Alison was an active participant in the story. She was hooked up to the safety rope as she climbed the wall, a bundle of energy and enthusiasm. Unfortunately, that enthusiasm manifested itself in lots of wild arm gestures. In a Facebook comment on the segment, one viewer wondered aloud if she had some kind of neurological affliction.

Alison called me in tears.

“Dad, what am I going to do?” she sobbed. “This is terrible. They might fire me. What if I can’t stop waving my arms?”

“Scooter, it’s just one day,” I said, marshaling all of my fatherly comfort. “You’ll be fine. You did great.”

That one Facebook comment was all it took. That’s when she really became a pro. She didn’t wave her arms anymore, and Alison and Adam became the Roanoke area’s favorite news duo. She always had great story ideas and she often made Adam her foil, a role he cheerfully played.

Over time, she became a regular noontime fill-in anchor on WDBJ, and she was still working toward that anchor position. In the meantime, she became a celebrity in the New River Valley, and those viewers who watched her every morning fell in love. They knew she was electric. They knew she had “it.”

I can tell you that Alison was smart, that she was naturally talented, that she was humble, but if there’s only one trait about her that you want to commit to memory, make it this: she was, above all, kind.

So many parents these days want to be friends with their children, and as a result, their kids grow up with no boundaries, no manners, and a sense of entitlement. Alison was our friend, and we were hers—Drew is the same way—but we also raised them both with expectations. We held them to standards of achievement. The only thing we were going to force them to do was be good human beings, and we tried to teach them how to make the best possible choices in life.

I believe Barbara and I were pretty damn good at parenting. Alison never got into trouble. The only time I really yelled at her was when she was about ten. We were horsing around on our boat when she hit me in the ear. It obviously wasn’t intentional, but that didn’t make it hurt any less; I felt like my eardrum had ruptured. I screamed at her, saying to never do that again. She went to the bow of the boat, curled up in a ball, and started to cry. I apologized instantly, but the incident haunts me still. I suppose it always will.

Like all fathers, I was the smartest guy in the world until my daughter got into her teens, but even when she noticed my IQ had dropped substantially, we didn’t butt heads all that often. She would, however, get ticked off at me for my wanting to fix things every time she had a problem, instead of just providing a listening ear and letting her solve it like an adult. That was the dad part in me coming out. I always wanted to fix her problems, to fight whatever injustices she encountered. She wasn’t shy about being irritated by this; she inherited a great deal of my personality and could be just as stubborn and willful as I am.

But all kids are stubborn at some point; when she was, she was still able to listen. She was always polite, and she had an otherworldly kindness. It was easy being Alison’s dad.

There was so much of me in Alison. Her fierce competitiveness and desire to win everything came from me. As an adult this desire bled into her career and that, plus her natural talent, allowed her to excel in journalism, just as she had excelled in athletics and academics. Alison always wanted to break the story, and the majority of the time she did. She was young for a TV news reporter, so very young, and already destined for an anchor’s chair in her mid-twenties. There is no telling where she could have ended up. But while Alison was determined to be the best, she didn’t step on other people in the process. She had a genuine grace and kindness.

They say that the light that burns brightest burns briefest, and there was always a part of me that feared, perhaps irrationally, that her light would burn so bright that it would flame out long before her time.

In the aftermath of her death, I’ve heard countless stories from her friends, teachers, coworkers, and perfect strangers about things she did for others, things I never would have known about had people not volunteered to share their Alison stories.

A typical example came from her time at WDBJ. It was just before Christmas and Alison, part of the skeleton crew still in the building, picked up the call. A desperate grandmother was on the other end of the line and spoke of a family with a struggling dad, a mom not in the picture, and children who were about to go without presents. All of the Christmas-assistance deadlines had passed and calls like these can sometimes be bogus—and bogus or not, they are generally met with a response of “I wish we could do something, but . . .”

Maybe Alison could tell the call was genuine, or maybe she was just willing to roll the dice, but she took a leap of faith. She made several calls and finally got in touch with an organization willing to help. Three children ended up with presents from Santa they wouldn’t have received otherwise.

There were so many little acts of kindness that only she and the recipients knew about, so many stories she never shared with me. I’m so thankful her coworker Heather Butterworth shared that one.

Throughout her short life, Alison developed relationships and trust. There is no better example than the mutual trust she shared with the court clerks, judges, and law enforcement in Jacksonville, Onslow County, and the state police attached to the area. While they had to share appropriate press releases with all local media, Alison was clearly a favorite. Once while visiting her, she took Barbara and me to meet the previous Onslow County sheriff. He sang her praises and invited us to join him and his wife “for suppuh.” I thought it quite unusual, but it clearly showed that Alison had left an impression on him. You don’t invite someone over for suppuh unless you’re fond of them.

She did once get “scooped” while she was working in New Bern, when she got an early tip from one of her police contacts that they were working on an active investigation. She was asked, however, not to break the story too early—the police wanted the media to keep it quiet until they wrapped up their investigation. The contact said this was because of its “sensitive nature.” Alison was ethical and complied, but when her competition found out, they were not. They broke the story. Afterward, there were some people in her news department that criticized her for not reporting it. I remember her telling me how much that stung, but she never second-guessed her decision. She knew she had done the right thing, and she stood up for her ethics in subsequent staff meetings. Ultimately, prematurely breaking the story backfired on the other station and Alison was hailed by upper management at hers. The respect she already had was multiplied.

The immediate benefit came in the form of getting more news tips. When law enforcement had information to feed the press, they would send out a release to all media outlets at the same time. They often seemed to make a mistake, though, and Alison would get the releases an hour or two before anyone else. Funny how that happened.

All of this leads to my favorite story about Alison’s news career. She was tipped off that there was going to be a major meth lab bust in the county. State as well as local police were involved, and the lead investigator assured Alison that they would be working long through the night at the crime scene. She requested the only live truck the station had for the entire area so she could lead the ten o’clock news with a live report. Before long, Alison and her crew were on the scene, raring to go.

At 9:45 p.m., the lead investigator called out to his team: “OK guys, that’s it. Let’s wrap it up.”

Alison panicked. Her story was tanking before her eyes. She went to the lead investigator and asked if they could please just stick around for a few more minutes for her live shot.

A lot of law enforcement officers would have shaken their heads no, however politely. The lead investigator didn’t.

“Sure, Alison, we’ve got you covered,” he said. He then instructed his men to fire up the flashing light bars on all the squad cars. He positioned his team in the background of the shot and armed them with clipboards, which they furiously scribbled on as the cameras rolled. It was a dramatic scene and made a great backdrop for Alison’s report. She nailed it.

Some readers will conclude, “Aha! Fake news!” But it wasn’t. Law enforcement busted a meth lab. The outcome was the same either way. It was a benign recreation, the kind of harmless small-town courtesy that could have happened in Mayberry, North Carolina, as easily as Jacksonville. Would officers in a major metropolitan market have done this for Alison? Given the trust she’d garnered, I’d like to think so. Those officers did it for her because she was held in high esteem and they knew her ethics to be beyond reproach.

What was it like being Alison’s dad? It was getting up each day with a heart bursting with pride. When I was running for Henry County’s Board of Supervisors just before she was killed, I only halfway joked that my campaign slogan was “I’m Alison’s dad.” It’s how I introduce myself still.

I worshipped my little Scooter. She will always be the best part of my life. I think she knew it, too.