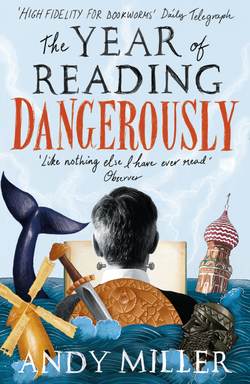

Читать книгу The Year of Reading Dangerously: How Fifty Great Books Saved My Life - Andy Miller - Страница 11

Book One The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

ОглавлениеMy life is nothing special. It is every bit as dreary as yours.

This is the drill. Every weekday morning, the alarm wakes us at 5.45am, unless our son wakes us earlier, which he sometimes – usually – does. He is three. When we moved into this house a year ago, we bought a Goodman programmable radio and CD player for the bedroom. The CD player, being cheap, is temperamental about what it will and will not play. When it works, which it sometimes – usually – doesn’t, the day begins with ‘I Start Counting’, the first track on Fuzzy-Felt Folk, an arch selection of children’s folk tunes on Trunk Records. (For a few weeks after we got the CD player, we experimented with alternative wake-up calls, from Sinatra, to the Stooges, to Father Abraham and The Smurfs, but the fun of choosing a different disc every night quickly turned into another chore, one more obstacle between us and our hearts’ desire – falling asleep.) ‘I Start Counting’ is a lilting and gentle song, a scenic shuttle-bus ride back to Morningtown, and the capricious CD player seems to like it. So we have settled for ‘I Start Counting’. ‘This year, next year, sometime, never …’

But on those mornings when the CD won’t take, the radio kicks in instead. These are the days that begin at 5.45am not with a soft dawn chorus of ‘I Start Counting’, but with the brutal twin reveille of Farming Today at ear-splitting volume and the impatient yelling of our only son, who has invariably been awake for some time. ‘Is it morning yet?’ he enquires, over and over again at the top of his lungs. We lie there, shattered. Someone somewhere is milking a cow.

I stumble downstairs and make a cup of tea. In the time it takes for the kettle to boil, I put some brioche in a bowl for my son – his favourite – and swallow a couple of vitamin supplements, cod liver oil for dry skin, and high-strength calcium (plus vitamin D) for bones. The calcium tablets are a hangover from a low-fat diet I put myself on four years ago, wanting to get in shape before Alex was born, one of the side effects of which, other than dramatic weight loss, was to make my shins ache from a real or phantom calcium deficiency. The pains soon went but the tablets have become another habit. At that time, my job was making me miserable. For too long I compensated by eating and drinking too much, wine at lunchtime and beer in the pub after work, with the result that for the first time, in my early thirties, I had become a fat man with a big, fat face. I shed three stone and have successfully kept the weight off, so that now, combined with the effects of sustained sleep deprivation, my face is undeniably gaunt. Acquaintances who haven’t seen me for a while look concerned and wonder whether I’m ok. ‘Have you been ill?’ they ask. I love it when they do this.

The kettle boils. I pour the hot water onto the Twinings organic teabag nestled in the blue cat mug which came from Camden market in the early 1990s, soon after my wife, Tina, and I first started going out, and which for reasons both of sentimentality and size remains her preference for the first cup of tea of the day.fn1 Sometimes I put out the mug and bag in readiness the night before, sometimes I don’t. I stir the teabag, pressing it against the side of the mug and squashing it on the bottom. Then I throw it in the bin, pour in the organic semi-skimmed milk, give the tea another stir and put the spoon to one side so I can use it again in an hour’s time to eat half a grapefruit – another surviving component of the low-fat diet. Actually, to all intents and purposes, I am still on the low-fat diet. I don’t drink beer any more and I rarely eat cakes, chocolate, biscuits, etc.

fn1. While the mug is blue, the cat itself is ginger.

If reading about this is sapping your spirit, you should try living it.

I take my wife her tea in bed. On a good morning, she will be waiting to take the hot cat mug from me, but sometimes, when I arrive in the bedroom, hot tea in hand, she has gone back to sleep and so I have to wake her up and cajole her into a sitting position. This does irritate me. I have been performing this small, uxorious duty for the last thirteen years; surely I am entitled to a measure of disgruntlement that she, luxuriating in precious minutes of sweet sleep I have already forgone on her behalf, cannot even be bothered to sit up? By now, three-year-old Alex has climbed into bed, though, so all slumber soon ceases. We lie in bed together, our whole family, complete. The best minutes of the day.

At this point, a fork appears in the road, depending on which of us has to go to London today. Tina and I both have jobs that permit us to work selected days from home. I look after Alex on a Thursday and his mother spends the day with him on Monday. On Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday, he is in nursery from 7.30am until 5.30pm. My mother-in-law helps with the pick-ups and drop-offs, as well as the washing and ironing. We pay her a small monthly retainer for these chores, which discreetly bumps up her pension and helps keep her grandson in chocolate buttons. However, by placing this arrangement on a financial footing, my mother-in-law is understandably reluctant to perform any grandmotherly tasks which fall outside her remit. We rarely arrive home after a long day at the office to discover, to our surprise and delight, someone has baked a cake or hidden a thimble.

So one of us goes to work in London, sometimes two of us. If it’s me I make sure I have enough time to eat breakfast, which is the same breakfast I eat every day except Sunday – half a grapefruit, a glass of orange juice from a carton, a slice of wholemeal toast and Marmite, and a mug of strong black coffee, brewed in a one-person cafétière. On Sundays I have black coffee, warm croissants and good strawberry jam. After six days of abstinence, the sudden Sunday combination of sugar, caffeine and pleasure propels me to a state of near-euphoria. This is usually the most alive I feel all week. For about half an hour, things seem possible.fn2

fn2. In the interests of full, Patrick Bateman-like disclosure, here are the brands which make up this breakfast. Grapefruit: Jaffa, pink, organic. Orange juice: Grove Fresh Pure, organic. Bread: Kingsmill, wholemeal, medium-sliced. Low-fat spread: Flora Light. Marmite: n/a. Coffee: Percol Americano filter coffee, fairtrade, organic, strength: 4. Sundays – All-butter croissants: Sainsbury’s, ‘Taste the Difference’. Jam: Bonne Maman Conserve, strawberry. I drink the orange juice from a type of Ikea glass called Svepa which, through a process of trial and error, I have determined is the perfect size for consuming a carton of orange juice in equal measures over four successive mornings. Then I go out and disembowel a dog.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein is said to have remarked that he didn’t mind what he ate, as long as it was always the same thing, although I imagine Wittgenstein rarely, if ever, bagged up his own packed lunch. If I am working in London, I always take the following with me: a ham sandwich, a tomato, a bag of baked crisps and an apple, which I eat at my desk.fn3 If I am having lunch in a restaurant with a colleague or a client, I still make and pack this exact combination of items and eat it twelve hours later on the train on the way home, where it tastes absolutely desperate. Why do I always do this? Because I don’t have the energy to be bothered to think about doing something different, even though the thing I am doing will, I know, stick in the throat.

fn3. ‘I sometimes feel like Nietzsche in Ecce Homo, feeling it appropriate to give an account of his dietary habits, like his taste for “thick oil-free cocoa”, convinced that nothing that concerns him could be entirely without interest.’ Michel Houellebecq, Public Enemies.

(FYI Mrs Miller skips breakfast – tut – and makes her own sandwiches only infrequently – tsk – although she does put a banana in her handbag and keeps a box of Oat So Simple instant porridge in her desk drawer.)

One or both of us leaves home at about 6.30am, certainly no later than 6.35am. We both prefer the 6.44am train, run by Southeastern Trains. There is very little chat on the 6.44; many of the other passengers are asleep. (The 7.03 lands you at Victoria at the height of the rush-hour crush, while the 7.22 usually fills up by Chatham, and its human traffic, having had an extra hour in which to wake up, make-up and caffeinate, is significantly rowdier.) But the 6.44am train has its drawbacks, too. We both travel in fear of sitting next to the woman who boards the train at Sittingbourne and without fail performs the same daily manicure: fingernails with emery board till Rainham, application of hand cream at Gillingham, greasy massage to Rochester. Once treatment is complete, the hands’ owner takes a power nap, mouth agape, to Bromley South, where she leaves the train. We refer to the woman as ‘Mrs Atrixo’. If she sits down next to one of us, we text the other: ‘Eek! Atrixo!’

Our train arrives in town. Then follows the bus or Tube ride. Then work. Work lasts all day, sometimes longer.

Meanwhile, at his nursery, my son enjoys a day of structured and unstructured activity in the company of a mixture of children and young women – few of whom are older than eighteen and none of whom are older than twenty-five. He might play with the Duplo™. He might pretend to be Doctor Who for a while. He might tell one of the girls what he got up to on his last ‘Mummy day’. We don’t know for sure because we’re not there. He usually has his breakfast and his lunch and his tea sitting at a little table with some of his friends. Of course, they are only his friends by virtue of being the children with whom he is obliged to pass much of his time (three days in every seven). They are more like colleagues than friends. At the end of the day, they all sit around the television, children and helpers, and watch a video until someone, a parent or grandparent, comes to collect them.

Sandwich, bath, a little more television, bed, stories, sleep. Also a telephone call from the parent – or parents – who may or may not get home in time to say goodnight.

The parental evening routine follows a very similar pattern, with half a bottle of wine and maybe some cooked food, sometimes even cooked from scratch. Sleep follows swiftly at 10pm, unless some detail of the day sticks in mind, some professional slight, some office skirmish to come.

That’s how the week goes. Weekends and family days are less restricted but still have their structures and patterns and duties – paperwork, haircuts, the weekly shop, visits from friends with children, long car journeys to close family. There is some fun but there is little in the way of spontaneity. We do not have the time. Then Monday comes around and we start counting all over again. ‘This year, next year, sometime, never …’

I assume we are happy. Certainly we love each other.

We have been working parents for three years. In that time I have, for pleasure, read precisely one book – The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown.

It is Thursday, and Thursday is a Daddy day. So we have packed the Wet Wipes and a change of trouser and after lunch the boy and I set off for Broadstairs.

Broadstairs is half an hour up the coast from where we live. For a part-time child-minding parent, it has several attractions to recommend it. The bay encloses a sandy beach with swings and trampolines. There is a small, old-fashioned cinema. Along the promenade, overlooking the bay, lies Morelli’s famous ice-cream parlour. And the long walk downhill from the station to the seafront almost guarantees an afternoon nap for members of the party travelling by pushchair.

However, this is a Thursday in late November. The cinema is closed. The swings and trampolines are shrouded in winter tarpaulins and the sea is too boisterous and cold for paddling. The rain that greets us at the station thickens as we trudge into town, facing the wind, and we have to shelter in the doorway of a charity shop to unpack the PVC rain cover, which flaps about uncontrollably until skewered to the metal frame of the buggy by ruddy red hands – mine. No one feels much like a snooze.

In Morelli’s, we are the only people eating ice creams. We also appear to be the only customers younger than sixty. Around us, pensioners eke out their frothy coffees and try not to make eye-contact with me. It has been my experience over the last few years that people are generally more at ease with the dad and toddler combo on TV than in reality, where it seems to disconcert them. Is the mother dead? Are we witnessing an abduction? In spring and summer, this place is full of life, with holidaying families and little children boogieing in front of the jukebox. But today the view across Viking Bay has vanished behind fogged-up windows.

We leave Morelli’s and walk up the promenade to the Charles Dickens museum. Hmm, some other time. But around the corner on Albion Street is the Albion Bookshop. I yank the pushchair up the steps, holding open the heavy door with one foot, and once inside try to find a corner where we shan’t be in anyone’s way, even though the shop is empty. Down the street a little way is another Albion Bookshop, a huge, endearingly dingy secondhand place – fun for Dad, who could easily lose hours in there, but less so for three-year-old boys. So while Alex decides which Mr Men book he would like, I browse this shop’s smaller selection of titles. There is a cookery section, a local interest section – Broadstairs In Old Photographs, etc. – and a Dan Brown section, with his four novels to date: The Da Vinci Code, Angels and Demons and the other two, and a plenteous range of spin-offs and tie-ins: Cracking the Da Vinci Code, Rosslyn and the Grail, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail.fn4 On the fiction shelves, between Maeve Binchy and The Pilgrim’s Progress, I am surprised to find Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. I pick it up – small format, £3.99, good value. The grinning cat on the front coverfn5 makes Alex laugh, so I take it to the till along with his choice, Mr Small.

fn4. I am aware The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail was published long before The Da Vinci Code. The Albion Bookshop has since closed down.

fn5. The book is orange, the cat is black.

It is time for us to go home. On the long climb back up the hill to Broadstairs station, the combination of sea air and ice cream finally catches up with Alex and he nods off. We find the space on the train next to the disabled toilet and, with my son still asleep and nothing to do for half an hour, I start to read.

‘Mr Small was very small. Probably the smallest person you’ve ever seen in your whole life.’

No, better wait till Alex wakes up. I turn my attention to the other book.

‘At the sunset hour of one warm spring day two men were to be seen at Patriarch’s Ponds …’

Later that evening, after reading Mr Small three times in a row, after Alex is tucked up and sleeping, I hazard a few more pages of The Master and Margarita. The two gentlemen at Patriarch’s Ponds in Moscow are Mikhail Alexandrovich Berlioz, editor of a highbrow literary magazine, and the poet Ivan Nikolayich Poniryov, ‘who wrote under the pseudonym of Bezdomny’. Before they have had a chance even to exchange pleasantries, a third character materialises:

‘Just then the sultry air coagulated and wove itself into the shape of a man – a transparent man of the strangest appearance. On his small head was a jockey-cap and he wore a short check bum-freezer made of air. The man was seven feet tall but narrow in the shoulders, incredibly thin and with a face made for derision.’

It seems this character, ‘swaying from left to right … without touching the ground’, is the Devil. But no sooner has He manifested himself, than the Devil vanishes. Shortly thereafter, Berlioz and Bezdomny are joined by a ‘professor’, a foreigner, country of origin unclear. The three of them have a rambling, opaque conversation. At the end of the first chapter, the action suddenly shifts to Rome at the time of Christ, and the palace of Pontius Pilate. What?

I cannot really fathom it. But the sheer novelty of reading a book of this sort after such a long lay-off is reward in itself. I am doing something difficult – good for me.

‘Your head will be cut off!’ the foreigner informs Berlioz in the course of their baffling chat, ‘by a Russian woman, a member of the Komsomol.’ (I have no idea what the Komsomol is.) After the mysterious detour to Rome in Chapter 2, back at Patriarch’s Ponds the editor and poet decide this ‘professor’ is certifiably crazy – ‘his green left eye was completely mad, his right eye, black, expressionless and dead’. Leaving Bezdomny to watch over this lunatic, Berlioz runs to telephone the authorities. (‘The professor, cupping his hands into a trumpet, shouted: “Wouldn’t you like me to send a telegram to your uncle in Kiev?” Another shock – how did this madman know that he had an uncle in Kiev?’)

Then this happens:

‘Berlioz ran to the turnstile and pushed it. Having passed through he was just about to step off the pavement and cross the tramlines when a white and red light flashed in his face and the pedestrian signal lit up with the words “Stop! Tramway!” A tram rolled into view, rocking slightly along the newly-laid track that ran down Yermolayevsky Street and into Bronnaya. As it turned to join the main line it suddenly switched its inside lights on, hooted and accelerated.

Although he was standing in safety, the cautious Berlioz decided to retreat behind the railings. He put his hand on the turnstile and took a step backwards. He missed his grip and his foot slipped on the cobbles as inexorably as though on ice. As it slid towards the tramlines his other leg gave way and Berlioz was thrown across the track. Grabbing wildly, Berlioz fell prone. He struck his head violently on the cobblestones and the gilded moon flashed hazily across his vision. He just had time to turn on his back, drawing his legs up to his stomach with a frenzied movement and as he turned over he saw the woman tram-driver’s face, white with horror above her red necktie, as she bore down on him with irresistible force and speed. Berlioz made no sound, but all around him the streets rang with the desperate shrieks of women’s voices. The driver grabbed the electric brake, the car pitched forward, jumped the rails and with a tinkling crash the glass broke in all its windows. At this moment Berlioz heard a despairing voice: “Oh, no …!” Once more and for the last time the moon flashed before his eyes but it split into fragments and then went black.

Berlioz vanished from sight under the tramcar and a round, dark object rolled across the cobbles, over the kerbstone and bounced along the pavement.

It was a severed head.’

Google tells me the Komsomol was the popular name for the youth wing of the Communist party of the Soviet Union and not the Moscow municipal tram network. But it’s academic: I’m in.

Right here is where my life changes direction. This is the moment I resolve to finish this book – a severed head bouncing across the cobblestones. Life must be held at bay, just for a few days, if for no reason other than to prove it can be done. I need to know what happens next.

Mikhail Bulgakov was born in Kiev in 1891 and died in Moscow in 1940 and at no point in-between, as far as I can establish, did he ever visit Broadstairs – never toured the Dickens Museum on a drizzly afternoon, never ordered a milkshake at Morelli’s. But let’s pretend he did. Imagine he manifested himself in the Albion Bookshop on Albion Street and discovered, as I had done, a copy of something called The Master and Margarita, with his name on the spine and cover. For a number of reasons, he would be astonished.

Macтep и Mapгapитa, usually translated as The Master and Margarita, was unpublished at the time of Bulgakov’s death – unpublished and, in one sense, unpublishable. For many years, it was available only as samizdat (written down and circulated in secret); to be found in possession of a copy was to risk imprisonment. Even its first official appearance in the journal Moskva in 1966 was censored; the first complete version was not published until 1973. Yet here it is in Broadstairs, available to purchase and in English to boot. ‘Бoжe мoй!’fn6

fn6. ‘Good Heavens!’

Another reason Bulgakov might be astounded to find his novel, in English, in a small Kent bookshop, might stagger out onto the pavement to catch his breath and, with a trembling hand, light a cigarette – ‘Я нyждaюcь в дымe!’fn7 – is that back when he died, the book remained unfinished. The first draft was tossed into a stove in 1930, after Bulgakov learned that his play, Cabal of Sanctimonious Hypocrites, had been banned by the Soviet authorities (who, unsurprisingly, did not care for the title). After five years’ work, he abandoned a second draft in 1936. He commenced a third draft the same year and chiselled away at it, making corrections and additions, until April 1940, when illness forced him to abandon his labours. A few weeks later, Bulgakov expired, exasperated. Macтep и Mapгapитa was completed by his widow, Elena Sergeevna; and it was she who spent the next twenty-five years trying to get it published. (‘Eлeнa, мoя любoвь, ecть кoe-чтo, чтo мы дoлжны oбcyдить …’fn8)

fn7. ‘I need a smoke!’

fn8. ‘Elena, my love, there is something we need to discuss …’

Have you read The Master and Margarita? It cannot be denied that the early part of the book is often inscrutable, a barrage of in-jokes savaging institutions and individuals of the early Soviet era which only an antique Muscovite or an authority on early twentieth-century Russian history would recognise or find amusing. And then there is the business with Rome and Pontius Pilate. Essentially, it is a book one has to stick with and trust.

Here are the bare bones of the plot. The Devil lands in Moscow, disguised as a magician. With Him is an infernal entourage: a witch, a valet, a violent henchman with a single protruding fang, and an enormous talking cat called Behemoth, a tabby as big as a tiger. The diabolic gang leave a trail of panic and destruction across the literary and governmental Moscow landscape. Sometimes this is grotesquely amusing, at others terrifying; frequently it is both. In a lunatic asylum we are introduced to the master, a disillusioned author whose novel about Christ and Pontius Pilate (ah, I see!) has been rejected for seemingly petty reasons. His response has been to burn the manuscript and shut out the world, even turning away his lover, Margarita, who ardently believes in his work.

Of course, I only appreciated the autobiographical significance of this in retrospect and the communistic targets of the satire remained obscure to me. In terms of the story itself, the promise of the severed head was slow to be realised. Had it not been for the half-forgotten kick of reading a book at all, I probably would not have carried on; for the first couple of days, I was compelled to do so by little more than my own stubbornness. This is only a book; I like reading books; this one will not get the better of me. But the more I read, the more I understood – or rather, understood that I did not need to understand. If I let it, the book would carry me instead.

The Master and Margarita begins as a waking nightmare. It has the relentlessness of a nightmare, the same persistent illogic one finds in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, but nastier, crueller – dead eyes, derision, severed heads, a cat whose mischievous grin betokens only black magic. Once in train, it is pitiless. But for the nightmare to take hold, the reader must fall asleep and wake up somewhere else.

Back in reality, though, I had to stay awake. I read in fifteen- or twenty-minute bursts, in lunch breaks or during Tikkabilla. It wasn’t a good way to go about it. To engage with this book when there were tasks to be performed, emails to be sent, ham sandwiches to be packed, or a purple dragon singing a song about being friends, was hard. It required sacrifices. Wine, TV and conversation were all postponed. It also required selfishness and cunning. ‘Just off to the Post Office,’ I would announce at the busiest hour of the day, ‘I won’t be long.’ And in the gloriously slow-moving queue, I would turn a few more pages.

At the beginning of the second half of the novel, Margarita is transformed into a witch at the Devil’s command. She accepts an invitation to His great Spring Ball. This is when both Margarita – and The Master and Margarita – take flight. She soars naked across Mother Russia – across the cities and mountains and rivers – transformed, ecstatic and free. And as she does, borne aloft on Bulgakov’s impassioned words, I felt the dizzying force of books again, lifting me off the 6.44, out of myself, away from Mrs Atrixo and her hands. How had I lived without this?

The Master and Margarita is a novel about many things, some obscure, others less so. To me, at this point in my life, it seems to be a book about books; and I love books. But I seem to have lost the knack of reading them.

After the ball, Margarita is granted a wish by the Devil. She asks only that the master be restored to her from the asylum. And then: ‘Please send us back to his basement in that street near the Arbat, light the lamp again and make everything as it was before.’

‘An hour later Margarita was sitting, softly weeping from shock and happiness, in the basement of the little house in one of the sidestreets off the Arbat. In the master’s study all was as it had been before that terrible autumn night of the year before. On the table, covered with a velvet cloth, stood a vase of lily-of-the-valley and a shaded lamp. The charred manuscript-book lay in front of her, beside it a pile of undamaged copies. The house was silent. Next door on a divan, covered by his hospital dressing-gown, the master lay in a deep sleep, his regular breathing inaudible from the next room … She smoothed the manuscript tenderly as one does a favourite cat and turning it over in her hands she inspected it from every angle, stopping now on the title page, now on the end.’

But of course an arrangement with the Devil has its price. Life cannot stay the same. For the master and Margarita to live forever, their old selves must die. She will stay at the Devil’s side, he will be free to roam the cosmos:

‘“But the novel, the novel!” she shouted at the master, “take the novel with you, wherever you may be going!”

“No need,” replied the master. “I can remember it all by heart.”

“But you … you won’t forget a word?” asked Margarita, embracing her lover and wiping the blood from his bruised forehead.

“Don’t worry. I shall never forget anything again,” he answered.’

It took me a little over five days to finish The Master and Margarita, but its enchantment lasted far longer. In death, the master and his book become as one. The book is no longer a passive object, a bundle of charred paper, but the thing which lives within his heart, which he personifies, which allows him to travel wherever and whenever he likes. The deal Margarita makes with the Devil gives him eternity. And this is how The Master and Margarita had made its journey down a century, from reader to reader, to a Broadstairs bookshop. Some part of that book, of Bulgakov himself, now lived on in me. The secret of The Master and Margarita, which seems to speak to countless people who know nothing about the bureaucratic machinations of the early Stalinist dictatorship or the agony of the novel’s gestation: words are our transport, our flight and our homecoming in one.

Which you don’t get from Dan Brown.

So began a year of reading dangerously. The Master and Margarita had brought me back to life. Now, if I could discover the gaps in the daily grind – or make the gaps – I knew I could stay there. Could I keep that spark alive in the real world, I wondered? Yes! Because to do so would truly be to never forget anything again. All I needed was another book; that was the deal. This was not reading for pleasure, it was reading for dear life. But, looking back, perhaps I should have stopped to think. With whom, exactly, had the deal been struck?

‘The master, intoxicated in advance by the thought of the ride to come, threw a book from the bookcase on to the table, thrust its leaves into the burning tablecloth and the book burst merrily into flame.’