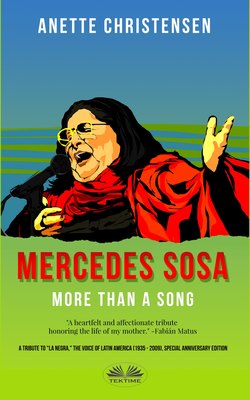

Читать книгу Mercedes Sosa - More Than A Song - Anette Christensen - Страница 9

Time before Exile

ОглавлениеSan Miguel, Tucumán, July 9, 1935

AT SANTILLÁN HOSPITAL, in northwest Argentina, twenty-four-year-old Ema del Carmen Girón has just given birth. It is seven o’clock in the morning. Her newborn daughter is safely asleep in her arms. The baby announced her entrance into the world with a hefty squall that could be heard all over the maternity ward. What no one knows is that one of history’s best voices has just made its first sound. Ema is grateful for this new and precious life she is holding in her arms, and, for a while, she forgets all the financial challenges that will come with raising a child. Ema has a job as a laundress, and her husband, Ernesto Quiterio Sosa, works in the sugar industry harvesting sugarcane and shoveling coal into the oven at the Tucumán Mill.

Through the half-open window, Ema can hear cannon salutes in the distance. She counts them—twenty-one. July 9 is Argentine Independence Day. Ema’s instinct is that it is not a coincidence that her daughter is born on this day. She confides in the midwife, who has just come back to the room, “This girl is going to be someone with great influence one day. Her birth is being welcomed by twenty-one salutes.”2 She keeps this conviction in her heart from this moment on.

EMA AND her husband, Ernesto, usually agree on everything, but when they have to give their newborn daughter a name, they run into some trouble. Ema wants to call her Marta, while Ernesto opts for Mercedes, after his mother, and Haydeé, after a well-liked cousin. Ultimately she gets the name Haydeé Mercedes Sosa, but for the rest of her life her mother will stubbornly call her Marta.3

Mercedes grows up in Tucumán, which is also called the Garden of the Republic. A semi-tropical and agricultural region with countless fields of sugarcane, flowers, and fruit trees, the smallest province in Argentina. It is in this oasis in the northwest corner of Argentina that Mercedes grows up with her older sister, Clara Rosa—also called Cocha—and her two brothers, Fernando and Orlando. The family resides in a poor, working-class area. The pink paint on the outer walls of their small, one-story house at Calle San Roque 344 is becoming black from the soot and smoke of the nearby factories, and in some places the paint is chipping off. The only light that gets into the house comes through two small windows with iron bars that face a narrow street where the children used to play, inventing their own games because they never had toys. Fortunately, they live close to the local park, which also has its ties to the date of Argentine independence, being named Parque de 9 Julio. It becomes a second home to them.

Growing up, Mercedes enjoys playing in the park with her siblings and the other children in their modest neighbourhood.4 She is always cheerful and connects with others easily. But sometimes she prefers to be on her own and withdraws to her favorite tree. She likes to sit leaning against the bark while watching the insects buzzing around her. She is a robust child in many ways, but she also has a sensitive, reflective side that makes her wonder why some people are rich while others are poor. Very early in her life, she has a developed feeling for right and wrong. It is a sensibility caused directly by seeing her parents work so hard to keep hunger from their doorstep. Even doing their utmost, they often can’t afford to buy food for their children. To distract their children from their hunger, they take them to the park to play every evening at dinnertime.3 To Mercedes, Saturdays are the best days because that’s when her father gets paid and the family can enjoy a meal of spaghetti with butter, the only hot meal they get all week. Often the hunger keeps her awake for hours at night.4

Still, later in life, Mercedes would come to say she had a happy childhood. “I do not wish to wail like someone who has lived in hunger, poverty, and cold. I lived my childhood in a poor house, which was however warmed up by the necessary feelings. My siblings and I always had the essentials, because we never lacked love. In this respect we were millionaires. Our parents not only sacrificed their lives, but they have been wise. They never put a burden on us for their sacrifices. They gave us everything they could, without revealing to us what they had to do to achieve this.”5

Mercedes never truly grows out of the mindset of poverty she grew up with, and it shapes her social consciousness and gives her sympathy for the poor, which, along with the love of her parents, shapes her ideology and provides the firm foundation on which she will continue to stand. As an adult she concludes, “Poverty has always chased us, but it never broke us down. It only helped us to be free and choose our way of thinking.”3

Mercedes has a close relationship with her grandparents. Her grandfather on her mother’s side is half French, while her grandparents on her father’s side are Amerindian with Quechuan roots, descending from the Inca empire. Mercedes is not aware of her Indian origins until her grandmother is dying and, in her delirium, starts speaking Quechua, but her new discovery instills in her a love for indigenous people and their culture, an affection that stays with her throughout her life.2

When Mercedes starts going to school, she quickly learns to read. She loves reading, and whenever it is time to cook at home, Ema orders Mercedes out of the kitchen and into her room where she can do so.6 It is important to Ema that Mercedes gain as much knowledge as she can, and Mercedes never resists. She is curious and eager, and she absorbs the words of one book after another like a sponge. It broadens her horizons and gives her an understanding of history, culture, and people of different backgrounds from her own. Mercedes also sings and dances throughout her childhood. It is like walking and talking to her. Yet she remains shy and doesn’t like to perform for others.

Then one day, in October 1950, when she is fifteen, her school music teacher, Josefina Pesce de Médici, discovers her ability to sing. To encourage Mercedes’ talent, she asks her to lead the school choir in singing the national hymn at a school celebration. Mercedes tries to hide in the back, but Medici tells her to step up in front of all the teachers, her fellow students, and their parents, and to sing loud and clear. She is nervous, terrified, but she does so well that her teacher and some of her friends decide, without telling her, to sign her up for a contest at the local radio station. “I remember singing from the far end of my life. However, it is not the same to sing at home and for the world. There is a date for this. I was fifteen years old, and, one day, school finished two hours early. There was a competition on the town’s radio station, LV12. I showed up more to play, rather than to sing.”5 Mercedes chooses to sing “Triste estoy” (I am Sad), a zamba by Margarita Palacios, under the pseudonym Gladys Osorio. She wins the contest, and the reward is a two-month contract with the radio station. This is the first stepping stone of her long career. Mercedes already knows that she wants to spend the rest of her life singing. A star has been born.

Her mother knows about the contest, but not Ernesto, her father, whom they know won’t approve. He finds out any-way, having recognized his daughter’s voice on the radio, and gets very upset. When Mercedes gets home, he slaps her in the face, which is something he has never done before. He doesn’t want his daughter to become a singer because he thinks it will move her away from the family and lead to a wild and dissolute lifestyle. He doesn’t believe there is any future in being a singer and wants his children to get an education so they can achieve more in life than he has. But to get the two months’ contract with the radio station, Mercedes, a minor, needs her parents’ signature, and Ema doesn’t want to sign behind her husband’s back. She is a clever woman who knows how to work on her husband, and, after a little persuasion, he finally gives in and signs the contract on the condition that Mercedes gets an education. To please him, she decides to become a dance teacher and study traditional Latin American dance, such as the Chacarera, Milonga, and Zamba.

The area where she grows up, with the influence of the indigenous culture of nearby Bolivia, inspires her to become a folk singer, although she could easily have made a career in opera instead and even considered it for a while. Her choice of education turns out to be an advantage for her career as an artist. But she can’t stop singing and continues to get many invitations to perform at public events. Her parents have no choice but to get used to the idea, and, little by little, they do. Soon the whole family is following her wherever she goes.4

As much as Mercedes loves singing, and as often as she is doing so for audiences, it remains an immense challenge each time she stands up before them. She is still shy and, despite appearances, suffers from severe stage fright. It is a fear she knows she must overcome if she is ever to fulfill what is becoming her dream.

EMA AND Ernesto are interested in politics. They don’t belong to any party, but they support Juan Perón, and even more so his wife, Evita, whom they admire for her outward beauty and her impact. Like them, Evita comes from a poor country region; unlike them (but perhaps like their daughter), she has worked her way out of poverty as an actress. Now, with her husband in office, she is responsible for the ministry of employment as well as the ministry of health. Her focus has been reforms to help the population’s poorest, and she founds a charitable organization, Eva Peron Foundation, responsible for building houses, schools, hospitals, and homes for children. Evita is also behind the legislation that gives women the right to vote for the first time. She is a heroine in the eyes of the working class and is loved by millions of Argentines, even while society’s right wing remains vehemently opposed to her.

At seventeen, Mercedes adores Evita and sees her as a real revolutionary. It is a major sorrow for her when, on July 26, 1952, Evita dies from cervical cancer, only thirty-three years old.2

IN 1957 Mercedes meets Manuel Oscar Matus, a composer and guitarist with a passion for traditional Latin American music, just like Mercedes. She falls head over heels for him and his songs despite the fact she is already engaged to someone else. “I was about to marry a rich man, but I married a poor man, and I never regretted it. That poor man was the author of the most beautiful songs I have been singing. If I hadn’t married him, it would have been a big mistake.”3

Oscar is also handsome and charming, with conclusive leftist ideals. They tie the knot on July 5, 1957. Mercedes doesn’t want to leave Tucumán, where she has lived all of her life, but Oscar convinces her to move to Mendoza, in the central-west part of the country. The city is a cultural meeting point for artists, where many new beneficial friendships are forged. Mercedes soon becomes pregnant, and on December 20, 1958, she gives birth to a son, Fabián. Making a living from their music is a tremendous challenge; the young family struggles financially and lives in poor conditions that remind Mercedes of her childhood. Though they would love to stay in Mendoza, the looming circumstances force them to move to Buenos Aires, leaving friends and close relatives behind as they begin the journey toward securing better and more stable lives.8

But even in the capital, they soon find they are not able to make a living from their music alone, so they take cleaning jobs and work as night porters at hotels. Mercedes, like her parents before her, is suffering under the burden of not being able to feed her family. When she goes to the market, she buys the leftover ribs without meat on them—the bones can give some taste to the soup she cooks. For the first time in her life, she feels discouraged and depressed. This is not how she imagined life to be—not for herself or her son.

Artistically, Oscar Matus is a tremendous inspiration to Mercedes, and she finds great joy in singing his songs. He encourages her to dedicate herself even more to the original Latin American music traditions and to revive folk music, a genre that is about to be forgotten due to the onward march of contemporary music. He is the producer of her first two albums, La voz de la zafra (Voice of the Harvest) and Canciónes con fundamento (Songs with a Foundation). They often give concerts for the students at the campus of the University of Buenos Aires, where Mercedes receives considerable recognition from the students, who are impassioned by her voice and engaging personality. She always takes the time to talk with them and listen to their ideas. But at the same time, as her popularity increases, an artistic jealousy arises in Oscar and it taxes on their marriage. The financial pressure, still extant despite Mercedes’ recent accomplishments, affects their marriage further. Regardless of her affection for Oscar’s music, she is uncertain of the durability of their marriage. It seems that it is only their passion for music that keeps them together.

STARTING IN Chile under the influence of Violeta Parra and Víctor Jara, the New Song Movement (Nueva Canción Movimiento) spreads in the sixties and seventies all over Latin America. It is associated with revolutionary music because its musicians aim to unite with their listeners in a demand for democracy and social justice, hoping to achieve social and political change through music. The lyrics put issues such as poverty, imperialism, democracy, human rights, and religious freedom into the spotlight and relate to marginalized people by putting words to their struggles and their hopes. The song “Plegaria a un Labrador” (A Prayer to the Farmer), by Víctor Jara, for instance, deals with the need for agricultural reforms, giving farmers the right to own the land they cultivate.

Free us from the one who rules us in poverty.

Bring us your kingdom of justice and equality.

Blow, like wind, the flower of the ravine.

Clean, like fire, the cannon of my rifle.

Your will be done, finally, here on earth.

Give us your strength and your courage to fight.

Such ballads, loaded with political messages wrapped in evocative, poetic metaphors, are perceived as threats to oppressive governments. One of Mercedes’ favorite songs, which in many ways becomes equivalent to her own struggle and resilience, is “Como la Cigarra” (Like the Cicada), by the Argentine poet and children’s book writer María Elena Walsh.

I was killed so many times.

I died so many times

however, here I am

reviving.

I thank misfortune

and I thank the hand with the dagger

because it killed me so badly

that I went on singing

Singing in the sun

like the Cicada

after a year

under the earth

just like a survivor,

that’s returning from war.

Mercedes Sosa and Oscar Matus are the key figures of the New Song Movement in Argentina. With a desire to exchange ideas with artists and movements throughout Latin America, they meet with eleven other artists and poets in Mendoza on February 11, 1963, to sign the New Song Movement (Manifiesto Fundacional de Nueva Canciónero). The movement emphasizes the continent’s indigenous history and native cultural roots, making use of folk instruments like the Andean flute, the quena, pan pipes, and the ten-stringed charango.9

In Argentina, Mercedes and Oscar work closely with Armando Tejada Gómez, an Argentine poet living in Mendoza. Gomez writes the songs, Matus composes the music, and Mercedes Sosa provides the voice connecting the two. Mercedes never writes her own songs—her strength lies in interpreting the songs of others and making them her own. “I fall in love with a song like one falls in love with a man. I love what I sing,”3 she says.She gets many of her songs from Víctor Jara and Violeta Parra of Chile. “Gracias a la vida” (Thanks to Life), by the latter of the two becomes one of the movement’s best-known songs worldwide, thanks to Mercedes’ interpretation, which is remarkably persuasive and personal, so much so that the song becomes her trademark for good. In the Unites States it is sung by Joan Baez, who also uses her popularity as a vehicle for social protest, expressing anti-imperialist views resulting from the Vietnam War.

OSCAR MATUS is a fervent communist and supports militant methods. Mercedes joins him in the party, but she can’t accept its militant approach so she resigns shortly after. Despite the brevity of her membership in the Communist Party, she is pigeonholed the rest of her life as one of its members, stigmatized by right-wing politicians as communist and a threat. Meanwhile, the communists take advantage of her name appearing in their member lists, at the same time blaming her for not being a “real” communist because she doesn’t break with the Catholic Church. However, Mercedes doesn’t allow anyone to place her in a box. She is what she sings of in the song “Como un pájaro libre” (Like a Free Bird), a free bird who follows her heart and her conviction in everything she does.

Her involvement in the New Song Movement is an ideal platform where she can combine her art and her concern about human issues. She is a woman with a leftist ideology, but she doesn’t see herself as a political leader and doesn’t like being labelled as a protester either.10 “Were they protesting songs? I've never liked that label. They were honest songs about the way things really are. I am a woman who sings, who tries to sing as well as possible with the best songs available. I was bestowed this role as a big protester, but it is not like that at all. I am just a thinking artist. Politics has always been an idealistic thing for me. I am a woman of the left, though I belong to no party and think artists should remain independent of all political parties. I believe in human rights. Injustice pains me, and I want to see real peace,”11 she says.

By insisting on being an artist, she gets some enemies on the left, while her leftist ideology makes her an enemy of the right. It is a dilemma, but it doesn’t stop her from taking a stand in her music. “Sometimes a song needs to have a social content. But the primordial issue is one of honesty. In Latin America, the mere act of an artist being honest is itself political,”12 she says, and advocates that artists have the same rights to have an ideology as everybody else.

IT IS not only political dilemmas Mercedes has to overcome. She is also facing a moral dilemma; she has become pregnant for the second time. Mercedes loves children and wants more but feels it is irresponsible of her.8 Her career is consuming almost all of her time and energy, and she is living a turbulent, often changing life that lacks the safe environment necessary to raise a child. She is already struggling to be the mother she wants to be to Fabián, and it is a huge challenge for her to reconcile her high expectations of herself as a mother with her ambitions as an artist. She is overwhelmed by the thought of having a second child, so when she becomes ill during her pregnancy, she decides to get an abortion, a decision that is hard on her and makes her feel that she is not able to live up to her ideals.8

This experience gives her a new understanding of young girls who have become pregnant against their will. She is not against the Catholic Church, but she sees it as a problem that the church is against teaching young adults about sexuality and fails to deal with the issue of children being molested by priests. Too many teenage girls die because they go to incompetent doctors who don’t know how to do the procedure safely and correctly. She believes that the average fifteen-year-old girl is not able to take care of a child, and that such girls need someone to speak up for them.8 As a result, she embarks on a lifelong journey, becoming a spokeswoman for women’s rights, and, in 1995, she is honored for her work by receiving the UNIFEM Award from the United Nations.13

Mercedes never regrets her decision about getting an abortion, but she nonetheless feels guilt over it frequently.

THE FINANCIAL pressure, their unpredictable lifestyle, raising a child, their disagreements over politics, and Oscar’s jealousy—which is causing him to mistreat her—is forcing her to question if she can keep her vows and stay in the marriage.4 She is desperate to get out but is caught in a bind. She has always been a “good girl.” She hadn’t had sex with anyone before she got married, and she has never been unfaithful to her husband. According to the norms of the time and the traditional values of the area, she has grown up believing that good girls don’t get divorced. Even so, she is considering another hard decision that goes against her values and her loyal personality. But while she’s deliberating, she learns that Oscar has been unfaithful and wants to leave her for another woman. He makes the decision for her, easing her conscience. But she still feels humiliated and finds it hard to accept that he has abandoned her. Hatred is not a feeling she normally possesses, but Mercedes feels hatred toward the other woman for the rest of her life. “I did not leave the marriage. He abandoned me. A Tucumána girl marries for life. That destroyed me.”4

Mercedes and Oscar have been married for eight years when Mercedes, thirty years of age, finally accepts that the marriage is leading to a dead end and consents to the breakup.

After the divorce, she feels heartbroken and lonely. She doesn’t even have a permanent place to stay and moves from one small pension to another with Fabián, who is now seven. Eventually, she decides to send Fabián to live with her parents in Tucumán. Her income comes from singing at nightclubs in Buenos Aires, but she doesn’t earn enough and has to get loans from some of her friends in order to survive. When the time comes to pay her friends back and she asks how much she owes, they all answer with variations of the rejoinder, “What money?” She is deeply moved by the sense of solidarity shown by her friends, who are artists struggling to make ends meet as well.

In 1965, Mercedes makes a significant step forward in her career. Thanks to the support of a very popular Argentine singer, Jorge Cafrune, who invites her to sing at the national folk festival in Cosquin, she gets a national breakthrough. At first, the festival committee doesn’t want her to sing as they consider her a communist, but Jorge Cafrune insists. Standing on the stage with her arm around Fabián, who she brings along whenever she can, she gives her thanks to Jorge Cafrune and the committee for the opportunity to sing. The song that provides her biggest breakthrough is almost prophetic, its lyrics ominously pointing toward what she is about to face.

Night is coming to me in the middle of the afternoon,

But I don’t want to turn into shadows,

I want to be light and stay.4

IN 1967, a new life is taking shape. Professionally, Mercedes is being introduced on the big international stages. She gives concerts in Miami, Rome, Warsaw, Lisbon, Leningrad, and many other cities. She becomes engaged to Francisco Pocho Mazzitelli, her manager, whom she had developed a friendship with while still being married to Oscar. In the beginning, he was just a very good, supportive friend, but the friendship has grown into love. He becomes crucial for the way Mercedes develops as a musician, as he likes many different genres and introduces her to both classical music and jazz. Their relationship helps keep Mercedes from becoming further depressed and lonely after her divorce. Francisco, or Pocho as she calls him, pulls her out of the darkness and Mercedes realizes that she has to hold onto him to stay in the light.4 They decide to get married in 1968. Pocho is a couple of years older than Mercedes, and he gives her the stability and peace she never experienced in her marriage with Oscar. He ends up being the love of her life, her true partner, and a substitute father for Fabián. He is also there supporting her through her grief when her father dies suddenly of a heart attack in June 1972, at the age of sixty-two.8

AS THE popularity of the New Song Movement grows among the working class, it becomes a real threat to the ruling dictatorships across the continent. Soon many of its artists face political oppression—censorship, persecution, intimidation—and some are forced into exile. One of the leaders of the movement in Chile, Mercedes’ good friend Víctor Jara, comes out in support of Salvador Allende for president. In 1970, Allende is inaugurated as the first socialist head of state in a Latin American country elected by democratic means. When he steps out in front of the masses to be paid tribute for the first time, there is a banner hanging behind him that says, “It is not possible to have a revolution without singing.”