Читать книгу A River Could Be a Tree - Angela Himsel - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 3

ОглавлениеIf Sunday belonged to family, then Saturday, the seventh day of the week, belonged to God.

The Sabbath began at sunset Friday night and ended at sunset Saturday night. On any Friday night, as the sun set behind the red barn and after we’d eaten the usual fried chicken and mashed potatoes and gravy for supper, we then-ten children gathered in the living room for Friday night prayer and Bible study. We took turns reading aloud from the church’s children’s Bible stories.

The gray, soft-backed books retold biblical events and were illustrated with black-and-white drawings: innocent Job, covered in boils, though he was sinless; Lot’s wife looking back over her shoulder, though warned not to, her eyes wide and frightened, before being turned into a pillar of salt, God’s punishment for her disobedience; Joseph, full of himself in the multicolored coat that got him into so much trouble.

I loved the stories, loved thinking about them and trying to figure them out. Joseph was thrown into a pit by his jealous brothers and then ransomed into slavery in Egypt. God destroyed the world in the flood, and only Noah and his family survived. Cain killed Abel, his own brother. They were harsh stories, and within them, God walked and talked and communicated with people. I was a literal-minded child, and I imagined God hanging out in their neighborhood, popping up on the street unexpectedly. I wished God would do that still, show up at the courthouse square in Jasper or maybe just appear in the backyard while we were playing red rover.

Friday evening ended with us kneeling at the couch and chairs, heads bowed, and our father led the prayer. “We thank you great God for your Sabbath, and for all of the spiritual blessings you’ve given us, and we pray that you will continue to bless us and open our minds to your Truth, in Jesus’s name we pray, Amen.”

I added my own private prayer: that my parents would get along; that my extended family would join our church so we could all be saved; that I would get into the Kingdom; and that I would receive God’s Holy Spirit.

_____________

On Saturday mornings, my father roused us with “Boys, girls, get up! You got to make hay while the sun shines!” We exited our rooms—there were two or three or four siblings per room, depending on the year, and we fought over access to the one bathroom. My brothers had it easy—they could go outside and pee behind the garage.

Then we ate a quick breakfast of oatmeal or Cream of Wheat. My mother was a devotee of anything natural and unprocessed and authentic. Wheat germ and blackstrap molasses were mainstays. We looked suspiciously on Cap’n Crunch.

My four brothers, scrubbed and pink-cheeked, ears jutting out below the almost military-style haircuts the church demanded, wore ill-fitting hand-me-down suits. My five sisters and I wore dresses that came to the middle of our kneecaps, in accordance with church doctrine. Just as Saturday was set apart from the rest of the week, I felt distinctly set apart from, and indeed superior to, our neighbors on the Sabbath. But still I longed to belong. I learned early to squelch personal desires like exchanging Valentine’s Day cards with my classmates, giving and receiving Christmas presents, eating turtle soup at my grandparents’ house. Anything that didn’t fit in with the life I was supposed to live. Anything that prevented me from getting closer to God.

Usually running late, which my father blamed on my mother, we piled into one of the rotating, fixer-upper, ancient Cadillacs and drove past weathered barns and billboards that urged us to “Chew Mail Pouch Tobacco.” Stacked on top of one another in the car, we grumbled and complained. We were bored. Jim took up too much room; Ed was deliberately bumping his legs up and down, causing Liz, who was seated on his lap, to lunge forward almost into the front seat. Wanda wanted the window rolled up because her AquaNet-ed hair was getting messed up, and Paul was sure that I had deliberately elbowed him. Within minutes my father yelled, “Would you kids PIPE IT DOWN!”

It was an hour and a half drive to Evansville, where we attended church services at a seedy gray building that the church rented from the Order of Owls, a fraternal society founded in South Bend, Indiana, in 1904 open to white men only. The church had no connection to the Owls, except to rent “The Owl’s Home” on Saturday afternoon. The church did not build or own houses of worship. This would have cost money and deprived it of money needed to preach the gospel to the world. Instead, rented movie theaters, Masonic lodges, auditoriums, and various other public spaces served as our “church” for Saturday services.

During the long ride, my father railed against the evils of drugs, miniskirts, evolutionists, and women’s libbers, all of which seemed to have overtaken America like a scourge in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was the time of Woodstock, the Summer of Love, the long-haired Beatles, and women burning their bras.

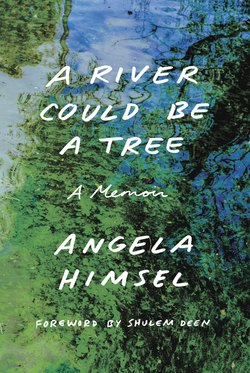

Incensed that women no longer knew “their place,” Dad made his case: “God created a role for everything in the universe. Just think what would happen if a river thought it could be a tree! God is not the author of confusion, it says that in the Bible, and women are confusing the way God intended them to be. They’re so mixed up these days that they’re mixing everybody else up. A wife is supposed to submit herself to her husband, for he is her head even as Christ is the head of the Church.”

The ministers often quoted this verse from the book of Ephesians, the apostle Paul’s letter to the church at Ephesus, to justify why wives should neither make decisions on their own nor work outside the home if their husbands didn’t want them to. In all things, one’s husband had final say.

“And Mama,” my father continued, “you should know that. It won’t work, with you pullin’ gee, and me pullin’ haw.” I imagined my father hitched to the plow, calling, “Haw!” while my mother shook her head and pulled in a different direction, “Gee!” He often accused her of deliberately undermining him. Which she did: covering for my older teenage siblings when they went out on Friday nights, the Sabbath, and turning a blind eye to my older sisters rolling up the waistband of their skirts to shorten them when they left for school.

I tuned out my father’s loud, tiresome, and contentious diatribes that made my heart jump and immersed myself in a word search puzzle or reading Trixie Belden. With books, I learned the useful art of tuning out things I didn’t want to hear.

When I was in my teens and the 1970s women’s movement—Ms. magazine; Roe v. Wade; Helen Reddy’s feminist anthem song “I Am Woman”—was in full swing, I challenged my father on this sexist and patriarchal attitude that I thought all religions should have long abandoned. While I still believed the Bible was God’s sacred word and contained laws that regulated how we should live, I thought the Bible could be interpreted in more than one way. I questioned why things had to remain the same.

I argued, “Daddy, I don’t believe that God created men and women unequal, or that one of us is supposed to serve the other. We’re all the same in the eyes of God.”

“Tater Doll,” my father literally threw up his hands and said, “you’re so stubborn, a team of twenty mules ain’t gonna change your mind. You would argue with the devil if you thought you were right!”

I took that as a compliment.

When we arrived at church, a deacon—maybe Mr. Davis or Mr. Cooper—stood at the door and greeted us with a big smile and outstretched hand. “Mr. Himsel, Mrs. Himsel.” Close to 200 people attended services with us every Saturday. They came from the tristate area: southern Indiana, southern Illinois, and northwest Kentucky. Until the mid-1970s, they were all white. Growing up, I was oblivious to the lack of racial diversity in the church. Though why would any black person wish to join a church that stated dogmatically that blacks were intended by God to be slaves because their ancestor, Noah’s son Ham, was cursed to be “a servant of servants unto his brethren”?

My mother greeted other women warmly by their first names, while my father offered a formal handshake and addressed everyone by “Mr.” and “Mrs.” We walked down the aisle to claim a row of hard metal chairs, where we would sit for the next two hours. Wanda, eight years older than me, and Mary, four years older, often sat with friends they’d made. My older brothers, Jim, Ed, and Paul, sat with us. Sarah, the youngest, sat between my parents and occupied herself with her coloring books. Abby, Liz, John, and I—all of us a little over a year apart in age—were clumped together, and we shared a hymnal, passed notes, and poked each other if someone was yawning loudly or if a whisper had become too loud.

In the back was a soda vending machine. The deacons had placed a piece of paper over the coin slot so we could not buy soda on the Sabbath, as we were forbidden to shop or spend money. While we were, of course, not allowed to work on the Sabbath, the church shifted its position on what exactly constituted “work” whenever “new truths” were revealed to Mr. Armstrong. At one point, we were not even allowed to buy gas for the car to drive to services; later, a new truth emerged to allow us to buy gas if it was an emergency. It was difficult to keep track of the ever-changing rules, and just as I’d figured something out, it was altered. It felt like walking on spiritual quicksand.

I liked to turn around in my chair and look at all of the other church members. I had yet to learn that staring was rude. There was a pale, emaciated woman with jet black hair. She fascinated me because she looked so different than everyone else. Only many years later did it occur to me that she was anorexic. Her best friend was one of the heaviest women in the church, a nice lady who would host us in her home when we needed to stay close by to attend church socials on Saturday night or church softball games on Sunday.

I remember being mesmerized by a woman scratching her elbow back and forth in an almost hypnotic way. White flakes fell from her elbow onto her black dress, like stars against a night sky.

Another couple, who had two sons, sat with each other during services, but didn’t live together. Though married, they had been forced to separate because she was previously divorced. According to church doctrine, anyone who got divorced and then remarried must leave his or her current spouse and either return to the one they’d divorced or remain unmarried.

I never knew how the family felt about the rule. If anyone disagreed with church doctrine, they didn’t dare verbalize it. Otherwise, the minister would show up at the house unexpectedly and give them a talking-to. He would remind them that Herbert Armstrong was God’s appointed one. If we wanted to grumble and complain like the Israelites had in the desert to Moses, then, just as the Israelites didn’t make it into the Promised Land, we wouldn’t make it into the World Tomorrow when Jesus returned. Church members lived in fear of those surprise visits.

The ministers had dropped by our house unexpectedly a few times. I never knew exactly why. My oldest sister, Wanda, who was more keenly aware of what was going on, thought it was because they wanted to remind us that they were in control. Or they wanted to make sure our parents were accurately tithing. Wanda surmised that the minister had told my parents not to have more kids, or maybe he was concerned about the spankings my father meted out, mostly to my older brothers, whom he deemed “rebellious.”

The spankings were, in fact, more like beatings. “Spare the rod, spoil the child,” was my father’s definition of parenting, at least of the older ones. Corporal punishment was encouraged, and when you went into the bathroom during church services, you would often hear the sharp slapslapslapslapslap of a mother’s hand against a child’s bare bottom. Not until the child stopped crying would she exit the stall, toddler in hand, the three-year-old’s face blotchy with crying. The mother felt no shame. In fact, she had done her parental duty.

I was completely unaware of the personal lives of any of the members. I found out that a man we all thought was upstanding actually liked young girls. One of the regular door greeters drank three martinis during Spokesman Club and got looped at restaurants. Several of the men spanked their wives to discipline them. And children were beaten regularly for any infraction.

When everyone was seated, the music director went to the front and said, “Please rise for the opening hymn.” Old and young voices joined together to sing songs from The Bible Hymnal, most written by Herbert Armstrong’s brother Dwight. The first song, “Blest and Happy Is the Man,” taken from Psalms 1, was a crowd favorite:

Blest and happy is the man Who doth never walk astray,

Nor with the ungodly men Stands in sinner’s way.

All he does prospers well,

But the wicked are not so;

They are chaff before the wind,

Driven to and fro.

I imagined myself, a fluff of chaff, being tossed about in the wind, never coming to a rest. I feared being wicked.

Next, another deacon offered the opening prayer. Heads bowed, eyes closed, hands clasped either in front or behind us, we listened. “Our merciful Father in Heaven, we thank you great God for bringing us here together on your Sabbath Day, and Lord, we pray that we will take the spiritual nourishment we need today. We pray that your work be done here on earth, and that you just strengthen and lift up your apostle, Herbert Armstrong, to witness to the nations and spread the gospel. In Jesus’s most holy name we pray, Amen.” The deacon’s prayer filled the creaky old room, and it was as if the entire congregation was one soul, praying to God, who bent His ear toward us, taking note of what was being asked.

Depending on the deacon, the prayer could go on for quite some time and incorporate asking God to help us remain strong in the face of persecution (“persecution” was code for one’s extended family or community opposing the church) and thanking God that we knew the Truth, and praying for those in our families who had not yet come to the Truth. Then we sat, placed our Bibles and notebooks in our laps, and listened to the sermonette, followed by the sermon.

Whether the topic of the sermon on any particular Saturday was “What Is Spiritual Sin?” or “Why Were You Born?,” it invariably became a shouting exhortation to remain steadfast in the church because these were the End Times. “You can be alive in Christ or dead in Adam!” the minister would scream. “You must love correction, and diligently seek the sin in yourself. Satan roams society like a lion seeking to devour you! God has raised up this church to witness for the End Times!

“God’s Holy Work must be done so Jesus can return,” the minister would remind us. “God needs YOU! God has called us—the weak and the poor—to confound the wise. Many are called, but few are chosen. This church and God’s chosen prophet, Herbert Armstrong, need your prayers, your loyalty, and your money to do the End Times work.”

My parents tithed ten percent of their income and gave it to the church; another ten percent they set aside to spend at the Feast of Tabernacles, plus there was a third tithe in the third and sixth years of a seven-year cycle that went to the poor, as well as the various “free will” offerings and pleas for money from Mr. Armstrong. My parents believed that our relatives, who disapproved of the money we gave the church, failed to understand that we’d been chosen for an important purpose: so Jesus could return. I was proud to be a part of God’s work on earth, even in a small way. As God’s soldier, I was heralding Jesus’s return to the earth. Nothing could be more important than that. I was proud that my family was chosen but also worried that too much pride was a sin. It was hard to calibrate how much pride was acceptable and how much would get me in trouble.

If Jesus didn’t return, it was the church’s fault. It meant that we were sinning, or not giving enough money to the church’s coffers so that Mr. Armstrong and the evangelists could spread the gospel worldwide. You could never pray enough, never give enough. God, who we were taught was good and merciful, was also insatiable in His demands. God was as inconsistent as the church, as my parents.

The screaming, dire certainty with which the minister announced that we were in danger of losing our eternal life—“If you are lukewarm in your love for God, if you are a spiritual DRONE, then your ETERNAL LIFE is at stake! You will NOT make it into the Kingdom!”—the fear of the End Times, the threats of the looming Lake of Fire where sinners would be tossed, and the incessant accusations that, as sinners, we needed to do more, be more, and give more, terrified me as a child. With their every exhortation, a sense of panic and doom squelched my childish optimism, my faith that tomorrow would come. We had to obey every command. Do it God’s way. Our lives, our salvation, were in jeopardy. The stakes were very high.