Читать книгу A Certain Mr. Takahashi - Ann Ireland - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеI don’t know whether to fear Or love you, ghost.

Does Colette have laugh and frown lines about her eyes now? From holding expressions too long? We’re old Kabuki actors posing a dramatic mie, crossing one eye over the other for the thousandth time.

Jean steps off the ferry onto the Victoria dock. It was a rough crossing, and she sways for a minute, holding on to the suitcase. A gust of wind sweeps across the concrete and billows her blouse into a tent. She squints at the little crowd of welcomers.

A horn bleats a sharp tattoo and, following the sound, Jean spies the old Volvo cruising to a stop by the waiting-room.

“Jean-ie!” A figure waves. A familiar mound of dyed blonde hair — Sam.

Jean skids over the pavement, suitcase castors veering every which way, her face pulled into a grin.

Sam unrolls the window. “Hurry up, honey. I’m in a no-parking zone!”

A car behind honks.

Jean dashes around to the passenger side, opens the door, and tosses her suitcase into the back seat. She jumps in beside her mother, and they kiss hurriedly.

Sam guns the motor and swings the car out of the ferry terminal in a cloud of dust and exhaust.

As Jean catches her breath she watches her mother. Nothing has changed. A fast shot of relief.

Sam turns and meets her stare. “You look terrific, old thing,” she says, and gives her daughter’s knee a quick squeeze.

“Do I?”

“You haven’t written in weeks. We were worried.”

“I’ve been busy, but I’ve thought of you lots.”

“Good!” Sam slaps the knee briskly. “The music must be going well for you.”

Jean understands this to be a question. Instead of answering she crosses her legs and looks out the window. The car purrs along, nearly soundless on the shelf of freshly laid asphalt. A cool breeze streams into her face: airconditioning.

They turn into a street parallel with the water. Big new houses set back from the road are surrounded by impossibly lush flowers in full bloom. Hibiscus, bougainvillea. Between buildings flash patches of glistening sea water.

“It’s lovely,” breathes Jean.

“Isn’t it?” Her mother is pleased, “We’re delighted to be out of Toronto. It was getting too big, too dirty.”

Goodbye Bowery, the screech of sirens, the howl of drunks, the smell of spilled Thunderbird. That word again.

“I read about you in Betty Dewart’s column,” Jean says.

“You saw that?” Sam chuckles. “Where?”

“Colette sent it to me. What’s this about a secret announcement?”

Sam’s fingers slide up and down the wheel. The car responds with a tremor, and Jean keeps an eye on the broken line fast disappearing beneath them.

“It wouldn’t be much of a secret if I told you.”

Jean backs off. “All right, I’ll wait.”

Funny how there are no people on the street and it’s not even dark yet. No one perching on his stoop with a beer can cheering on a ball game. No Puerto Rican kids hanging out on the corner with a ghetto blaster cranked to high decibel screech.

“Colette arrived from Toronto,” says Sam.

“What? She’s here already?” exclaims Jean. Her chest tightens. For some reason she assumed they’d arrive at the same moment.

“She took the red-eye last night. Do you realize this is the first time the family’s been together for two and a half years?”

“How is she?”

The car cruises to a halt to let a small dog cross the street.

“Same as usual,” says Sam. “Except she’s taken to wearing army fatigues.” The car rounds a corner. “Nelson’s influence, I gather.”

They travel on for a while in silence.

“And how’s Dad?”

“Your father’s fine,” says Sam. “By the way, an old pal of yours is coming to Vancouver this weekend. A fellow New Yorker.”

“Oh? Who?”

Sam continues to look straight ahead.

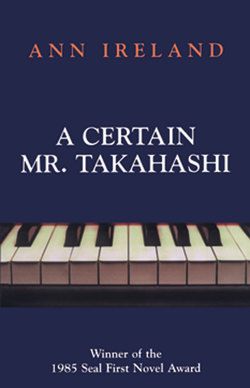

“A certain Mr. Takahashi.”

“Yoshi?” Jean tries for a tone of normal interest. “That’s certainly a coincidence.” She swallows. “Does Colette know?”

“She must. There’s a big ad in the morning paper. He has a new record.”

“Ahhh.” Jean lets the news sink in. A bee of anxiety zaps crazily around in her stomach.

“Here we are!” says Sam, rolling the tires over a long driveway of fresh gravel. “Our little pied-à-terre.”

Hooray, I’m back, Colette. I’m home!

Colette was living with her boyfriend in an apartment near the old police station. I couldn’t wait to surprise her—two years. I’d changed a lot.

Weird walking through that part of Toronto, the Polish market, with its bakeries, pirogi joints, and sausages hanging in windows. She’d written me about her apartment, a third-floor walk-up next to an auto-body shop. I still couldn’t imagine her with her own place, away from Dundeen Square. Did she take her dresser with her? I forgot to look. Would she still live in spartan Japanese-style simplicity? She’s still Colette, I reminded myself, pushing through crowds of people on the narrow sidewalk. She’d be pleased to see me — but what if she wasn’t?

The door opened to my knock, and her face spread with surprise. “Jean!” Then we hugged like I imagined we would and of course cried because it had been so long. Oh, Jean. Oh, Colette. Then we laughed at our red eyes and wet cheeks, and she pushed me into the apartment where there were walls lined with Mexican serapes and Moroccan cowbells and posters from rallies and rock concerts. A giant photo of Karl Marx hung at the top of the stairway. I guess her Japanese phase was over. She went into the kitchen to make camomile tea and told me to roll a joint, the stuff was on the table in the wooden box.

“Where’s the man?” I looked for signs of his existence.

“He’s out,” she said. “At a political meeting.”

“Oh.”

“And what have you been doing for the last two years?”

There was so much to tell, and I began to wonder, just for a moment, if I’d be able. How could I explain going to school in Manhattan? “I sit in Washington Square, Colette, and read a book while all around people roller skate, drop flaming swords down their throats, deal dope—everything’s there, things you can’t imagine-and, Colette, the man I’ve been going with, the married professor who publishes stories in the New Yorker—it’s over now. He decided to stick with his wife and it hurts, Colette, sweet glorious pain.”

I sat dumbly, words lodged in my throat like dry toast. We watched each other over aromatic tea, checking out adult faces and bodies. I’d gained weight and become plumpish, rosy-cheeked. I looked over her shoulder at the bookshelf and read titles. Where would our conversation begin when there was so much?

Then something went click, a gear I’d sworn not to use, the beginning of the end of us. I said, “Do you remember the time … ?”

And laughing, resigned to it but a little ashamed, we dug into reminiscence, that durable cactus. Yoshi.

That’s all I had to say. Then “Montreal”. Our smiles broadened, overlapped.

“How did you feel when you realized we’d be staying in the room with him?”

“Terrified,” I admitted. “Thrilled.”

“And when the bellboy came in … ”

“ … and there we were sprawled on the floor on hotel mattresses. He didn’t bat an eyelash.”

“But he wondered, all right.” A trill of shared laughter.

“After all, what were we, seventeen, eighteen?”

Brief silence as each re-enacted the scene. More tea.

“What a remarkable dream it was,” Colette said, dead serious.

I shook my head. “Nothing like it can happen again.”

We continued the story, incident by incident, breath by shared breath, as if we were one person all those years. We remembered his house with the yellow door, the black car, the thick white rug, the jasmine tree in a pot, his yukata and olive skin. And, Colette, the music.

Marijuana lapsed into the Italian wine I’d brought, and Colette produced freshly baked oatmeal bread and a tub of peanut butter. She had furniture, clothes, dishes, shapes of her own. I caught a sniff of the interior of her fridge, later used her bathroom and saw his toilet things neatly stacked on the tub’s edge. Scissors, toenail clippers, razor, Brut.

Our talk surged forward as if we needed to pass through each phase of our shared life just to get to this point.

We were lying on the couch, half drunk, unable to finish a story because we were laughing so hard, when he came in. His shadow crossed the rug before us, elongated by the evening light. Colette pulled herself together and made the introduction.

“Nelson,” Colette waved. “I’d like you to meet my sister, Jean, who you’ve heard so much about.”

We kissed gently, on the lips. His beard grazed my cheek. He was dark, older, long-haired, and wore a blue turtleneck and jeans. He must have heard a piece of the conversation, or felt a tone.

“Going over old times?”

He said it lightly, but I felt caught out, guilty. Colette looked once at me, then almost visibly moved her heart from us to him and said, “Maybe that’s all we have now.”

My own heart crumpled as if kicked. Colette, I could not bear what you said, its naked tone, the grave disloyalty. The man was there, smiling and wise.