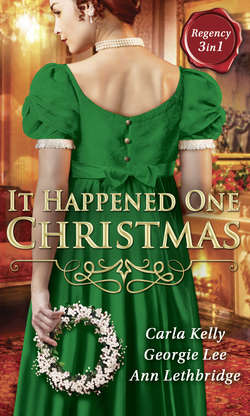

Читать книгу It Happened One Christmas: Christmas Eve Proposal / The Viscount's Christmas Kiss / Wallflower, Widow...Wife! - Ann Lethbridge - Страница 6

ОглавлениеChapter One

‘Surely you never expected to stay at Walthan Manor, Master Muir?’

What a self-righteous prig Midshipman Tommy Walthan is, Sailing Master Benneit Muir said to himself. He’s a pipsqueak, a lump of lard and an earl’s son. God spare me.

‘Oh? I assumed that since you commissioned me to drill you in navigation methods, that I would be more useful close by.’ That was the right touch. Ben didn’t hold out much hope that any amount of tutoring would improve the wretched youth’s chances of passing his lieutenancy exams next year in 1811, but it was nearly Christmas and the sailing master had no plans.

There wasn’t time to go home to Scotland, or much reason. The girls Ben had yearned for years ago were all married and mothers many times over. His mother was gone, his father too old to travel and his brothers in Canada.

Walthan gave that stupid, octave-defying titter of his that felt like fingernails on slate. It had driven other midshipmen nearly to distraction, Ben knew, but at least it was one of the irritants that spurred others to pass their exams and exit the HMS Albemarle as quickly as possible. Even the captain, an amazingly patient man, had remarked that nothing short of the loss of his ship would ever rid them of Tom Walthan. No other captain wanted him, no matter how well connected his family.

‘Stay at Walthan? Lord, no, Master Muir! I can’t imagine what my mama would say, if you stepped from this post-chaise with your duffel. Better find a place in the village, sir.’ The midshipman coughed delicately into his sleeve. ‘You know, amongst people more of your own inclination.’

Ben decided that the village would be far enough away from Walthan’s laugh, but he didn’t intend to sink without a struggle.

‘You’ll shout my room and board?’ Ben gave the midshipman the full force of the gallows glare he usually reserved for the quarterdeck. It wasn’t that he couldn’t afford to pay his own whack, but he was tired of being cooped up in the post-chaise all the way from Plymouth with Tom Walthan, the midshipman from Hades.

‘If I must,’ Walthan said, after a lengthy sigh, that made Ben feel sorry for the lad’s nanny, gone now. He had no doubt that Walthan’s mother had long since given up on him.

‘I fear you must pay,’ Ben said. ‘Do you know of lodgings in Venable?’

‘How would I?’ Walthan waved his hand vaguely at the cliff edges and sea glimpses that formed the Devon coast. ‘Venable has a posting house. Try that.’

Ben gave an inward sigh, nothing nearly as dramatic as Tom Walthan’s massive exhalation of breath, because he was not a show pony. He had hoped to find a quiet place to finally slit the pages on The Science of Nautical Mathematics and settle down to a cosy read. Posting houses were not known as repositories of silence.

‘Besides, I still must explain why I have asked you here to help me study for my exams,’ Walthan said. ‘The last time I wrote Mama, I was pretty sure I would pass.’ Another delicate cough. ‘And so I informed her.’

‘That attempt in Malta?’ Ben asked. He remembered the barge carrying four hopeful midshipmen into the harbour where an examination board of four captains sat. Three had returned excited and making plans, Walthan not among them. The laggard’s disappointment was felt by everyone in the Albemarle’s wardroom, who wanted him gone.

‘Those were trick questions,’ Walthan said, with all the hurt dignity he could muster.

Ben swallowed his smile. ‘Oh? You don’t see the need of knowing how to plot a course from the Bight of Australia to Batavia?’

‘I, sir, would have a sailing master do that for me,’ Walthan said. ‘You, fr’instance. It’s your job to know the winds and tides, and chart the courses.’

Hmm. Get the idiot out of his lowly place on the Albemarle and he becomes almost rude, Ben thought. ‘And if I dropped dead, where would you be?’ The little nuisance was fun to bait, but the matter was hardly dignified, Ben decided. ‘Enough of this. I will do my best to tutor some mathematics into you. Stop here. I’ll see you tomorrow at four bells in the forenoon watch at Walthan Manor.’ Ben shook his head mentally over the blank look on the midshipman’s face. ‘Ten o’clock, you nincompoop,’ he said as he left the post-chaise and shouldered his duffel.

Now where? Ben stood in front of the public house and mail-coach stop, if the muddy vehicle visible in the ostler’s yard was any proof of that. He peered through the open door to see riders standing shoulder to shoulder, hopeful of something to eat before two blasts on a yard of tin reminded the riders to bolt their food or remain behind. Surely Venable had more to offer.

As he stared north and then south, Ben noticed a small sign in the distance. He walked in that direction until he could make out the words, Mandy’s Rose. Some village artist had drawn a rose in bud. Underneath he read, ‘Tea and good victuals.’

‘Victuals,’ he said out loud. ‘Victuals.’ It was a funny word and he liked the sound of it. He saw the word often enough on bills of lading requiring his signature, as food in kegs was lowered into the hold, another of his duties. Oh, hang it all—he ran the ship. Victuals. On land, the word sounded quaint.

‘Good victuals, it is,’ he said out loud as he got a better grip on his duffel. He tried to walk in a straight line without the hip roll that was part of frigate life. Well balanced aboard ship, he felt an eighteen-year awkwardness on land that never entirely went away, thanks to Napoleon and his dreams of world domination.

A bell tinkled when he opened the door to Mandy’s Rose. He hesitated, ready to rethink the matter. This was a far more genteel crowd than jostled and scowled in the public house. He doubted the ale was any good at Mandy’s Rose, but the fragrance of victuals overcame any shyness he felt, even though well-dressed ladies and gentlemen gazed back at him in surprise. Obviously posting-house habitués rarely came this far.

His embarrassment increased as his duffel seemed to grow from its familiar dimensions into a bag larger than the width of the door. That was nonsense; he had the wherewithal to claim a place at any table in a public domain. He leaned his duffel in the corner, suddenly wishing that the shabby thing would crawl away.

The diners had returned to their meals and there he stood, a good-enough-looking specimen of the male sex, if he could believe soft whisperings from the sloe-eyed, dark-skinned women who hung about exotic wharves. He put his hand on the doorknob, ready to stage a retreat. He would have, if the swinging door to what must be the kitchen hadn’t opened then to disclose a smallish sort of female struggling under a large tray.

He would never have interfered with her duties, except that a cat had followed her from the kitchen and threatened to weave between her feet.

Years of battle at sea had conditioned Ben Muir to react. Without giving the matter a thought, he crossed the room fast and lifted the tray from her just before the cat succeeded in tripping her. Two bowls shivered, but nothing spilled.

‘Gracious me, that was a close call,’ the woman said as she picked up the cat, tucked it under her arm and returned it to the kitchen, while he stood there looking at her, wondering if this was Mandy’s rose.

She was back in a moment, her colour heightened, a shy look on her face as she tried to take the tray from him. He resisted.

‘Nay, lass, it’s too heavy,’ he said, which earned him a smile. Thank the Lord she wasn’t angry at him for disrupting what was obviously a genteel dining room by standing his ground with the tray.

‘I do tend to pile on the food,’ she said. Her accent was the lovely burr of Devon. He could have held the tray for hours, just to listen to her. ‘Stand here, then, sir, and I’ll lighten the load.’

He did as she said, content to watch her move so gracefully from table to table, dispensing what was starting to make his mouth water. A touch of a shoulder here, a little laugh there, and he knew she was well acquainted with the diners she served. Small villages were like that. He remembered his own in Scotland and felt the sudden pang of a man too long away.

And all this because he was holding a tray getting lighter with every stop at another table. In a moment there would be nothing for him to do, but he didn’t want to leave.

‘There now.’ She took the tray from him. ‘Thank you.’

He nodded to her and started for the door. He didn’t belong there.

She never lost her dignity, but she beat him to the door and put her hand in the knob. ‘It’s your turn now, sir. What would you like?’

‘I don’t belong here,’ he whispered.

‘Are you hungry?’

‘Aye. Who wouldn’t be after breathing the fragrance in here?’

‘Then you belong here.’

It was more than the words. Her eyes were so frank and kind. He felt the tension leave his shoulders. The little miss wanted him to sit down in a café that far outranked the usual grub houses and dockside pubs where he could be sure of hot food served quickly and nothing more. Mandy’s Rose was worlds away from his usual haunts, but he had no desire to leave.

She escorted him to a table by the window. The wind was blowing billy-be-damned outside. He thought a window view might be cold, but he could see it was well caulked. No one seemed to have cut a single corner at Mandy’s Rose.

‘Would you like to see the bill of fare?’ she asked.

‘No need. Just bring me whatever you have a lot of,’ he told her.

He blushed like a maiden when she frowned and leaned closer, watching his lips. ‘I’m not certain I understood you, sir,’ she said, equally red-faced.

He repeated himself, irritated that even after years away from old Galloway, his accent could be impenetrable. He gave her a hopeful look, ready to bolt if she still couldn’t understand him. A man had his pride, after all.

‘We have a majestic beef roast and gravy and mounds of dripping pudding, and that’s only the beginning.’

Damn his eyes if he didn’t have to wipe his mouth. Gravy. He thought about asking her to bring a bowlful and a spoon, but refrained.

‘And to drink?’

‘Water and lots of it. We’ve been a long time on blockade.’

She nodded and went to the kitchen, pausing for another shoulder pat and a laugh with a diner. He watched her, captivated, because when she laughed, her eyes shrank into little blue chips. The effect was so cheerful he couldn’t help but smile.

She paused at the door and looked back at him. Her hair was smooth, dark and drawn back in a ribbon, much as his was. He had stood close enough to her to know that she had freckles on her nose. That she had looked back touched him, making him wonder if there was something she saw that she liked. He knew that couldn’t be the case. He was worn out and shabby and ready to leave the blockade behind, if only for a few weeks. The ship would be in dry dock for at least six weeks, but he was the sailing master and every inch of rope, rigging, ballast and cargo was his responsibility.

He had agreed—what was he thinking?—to devote three weeks to cram enough navigational education into Thomas Walthan’s empty head for him to pass his lieutenancy exams. Whether or not he succeeded, Ben had to report to Plymouth’s docks in three weeks, because duty called. He glanced out the window, where sleet scoured the cobblestones now. At least he would go back well fed and with the lingering memory of a kitchen girl who looked back at him. That was about all a man could ask for in perilous times.

‘Auntie, we have the most amazing man seated by the window,’ Mandy said. ‘He’s in a uniform, but I don’t know what kind. He’s not a common seaman. He’s from Scotland. He wants whatever we have the most of and lots of water. And, Auntie, he has the most amazing tattoo on his neck. It looks like little dots.’

‘Mandy’s Rose doesn’t see too many tattoos,’ Aunt Sal said. ‘Earrings?’

‘Heavens, no!’

Aunt Sal smiled over the gravy she stirred, then set it on a trivet. She turned to carve the beef roast, poising her knife over the roast. ‘Here?’

‘Another inch or two. There. And lots of gravy. You should have seen his eyes follow the gravy I served Vicar Winslow. And your largest dripping pudding. That one. We have some carrots left, don’t we?’

‘Slow down, child!’ Sal admonished as she sliced a generous hunk of beef and slathered gravy on it. She poured more gravy in a small bowl while Mandy selected the biggest dripping pudding and set it on a plate all its own. She slid the bowl on, too, added cutlery and took it into the dining room.

She stopped a moment, just to look at the Navy man. Palm on chin, he was looking out the window at the driving sleet. He had taken off his bicorn hat and his hair was a handsome dark red, further staking his claim as a son of Scotland. He looked capable in every way, but he also looked tired. The blockade must be a terrible place, she thought, as she moved forward.

‘Dripping pudding first and lots of gravy,’ she said to get his attention. ‘I’ll bring some water and then there will be beef roast with carrots. Will that do?’

‘You can’t imagine,’ he said, tucking his napkin into the neck of his uniform.

She set down the plate and smiled as he poured a flood of gravy over the pudding. A cut and a bite was followed by a beatific expression. Nothing made Mandy happier than to see pleasure writ so large on a diner’s face. She wanted to sit down and ask him some questions, but Aunt Sal had raised her better.

Or had she? Before she realised what had happened, she was sitting across from him at the small table. She made to rise, astounded at her brazen impulse, but he waved her back down with his knife and gave her an enquiring look.

‘Where are my manners, you are likely wondering?’ she said.

‘I could see a question in your eyes,’ he said. ‘Ask away, as long as you don’t mind if I keep eating. I’m used to questions at sea.’

He had a lovely accent, Mandy decided, and she could understand him now. How that had happened in ten minutes, she didn’t know. ‘It’s this, sir—I was wondering about your uniform. I know you’re not a common seaman, but I don’t see an overabundance of gold and folderol on your blue coat.’ She smiled, which for some reason made him smile. ‘Are you a Quaker officer of some sort and must be plain?’

He set down his knife and fork, threw back his head and laughed. Mandy put her hands to her mouth and laughed along with him, because it was contagious.

‘Oh, my,’ he said finally. ‘I’ll have to share that in the wardroom, miss…miss.’

‘Mandy Mathison,’ she said.

‘You’re Mandy’s Rose?’ he asked, as he returned to the dripping pudding.

‘I am! My name is Amanda, but Aunt Sal has always called me Mandy. She scolded me one day when I was two and pulled up a handful of roses, then cried because of the thorns.’

‘An early lesson, lass, is that roses have thorns.’

‘So true. When she leased this building and started the tea room, she named it for me. But, sir, you haven’t answered my question.’

‘I’m hungry,’ he said and Mandy knew she had overstepped her courtesy. She started to rise again and he waved her down again. ‘I’m senior warrant officer on the Albemarle, a forty-five frigate. Forty-five guns,’ he explained, interpreting her look. ‘It’s only been in the last three years that we masters have had uniforms.’ He held up one arm. ‘This is the 1807 model. I hear the newer ones have a bit of that folderol on the sleeves now.’

‘I shouldn’t have called it that,’ she said. ‘What do you do?’

He chewed and swallowed, looking around. Mandy leaped up and hurried into the kitchen again, returning with the pitcher of water and a glass.

‘I forgot.’ She poured him a drink.

He drank it down without stopping. He held out the glass again and he did the same. He let out a most satisfied sound, somewhere between a sigh and a burp, which made the vicar turn around.

‘We drink such poor water on blockade.’ He picked up his knife and fork again and made short work of the dripping pudding. Mandy returned to the kitchen with empty plates from other diners and came back with that healthy slab of roast and more gravy, setting it before him with a flourish, because Aunt Sal had arranged the carrots just so.

‘Sit,’ he said, as he tackled the roast beef. After a few bites, he took another drink. ‘I’m in charge of all navigation, from the sails and rigging, to how the cargo is placed in the hold, to ballast. Everything that affects the ship’s trim is my business.’

‘I’m amazed you can get away from your ship at all,’ Mandy said. She hesitated and he gave her that enquiring look. ‘Are you going home for Christmas?’

‘Too far, lass.’ He leaned back and gave her an appraising look. ‘Do you know Venable well?’

‘Lived here all my life.’

‘In a weak, weak moment, I agreed to help Thomas Walthan cram for his lieutenancy examinations.’ He lowered his voice. ‘He’s a fool, is Tommy, and this will be his fourth try. I’ll be here three weeks, then it’s back to Plymouth and those sails and riggings I mentioned. Do you know the Walthans?’

Oh, did she. Mandy decided that after this meal she would probably never see the sailing master again, but he didn’t need to know everything. ‘They’re the gentry around here. His father is Lord Kelso, an earl.’ She couldn’t help her smile. ‘Thomas can’t pass his tests?’

The master shook his head. ‘I fear there’s a small brain careening around in that head. My captain wants him to pass and promote himself right out of the Albemarle.’

He returned to his meal and she cleared away the dishes from the last group of diners, the vicar and his wife, who came in every day at noon.

‘I believe you’re flirting with him,’ the vicar’s wife whispered, as Mandy helped the old dear into her coat. ‘You’ll recall any number of sermons from the pulpit about navy men.’

Mandy nodded, hoping the master hadn’t overheard. She glanced at him and saw how merry his eyes were. He had overheard.

‘I’ll be so careful,’ Mandy whispered in her ear as she opened the door.

Reverend Winslow took a long look at the master and frowned.

Now the dining room was empty, except for the sailing master, who worked his way steadily through the roast, saving the carrots for last. When he thought she wasn’t looking, he spooned down the last of the gravy.

‘Is there anything else I can get you?’ she asked, determined to wrap herself in what shreds of professionalism remained, after her battery of questions.

‘What else is in your kitchen?’ he asked.

‘Just a custard and my Aunt Sal,’ she replied, which made him laugh.

‘How about some custard? Maybe I can chat with your aunt later.’

She returned to the kitchen, just in time to see Aunt Sal step back from the door.

‘I’ve been peeking. He’s a fine-looking fellow and that is an odd tattoo,’ Sal whispered. ‘He certainly can pack away food.’

‘I don’t think life on the blockade is blessed with anything resembling cuisine. He’d like some custard.’

Aunt Sal spooned out another massive portion, thought a moment, then a more dainty one. ‘You haven’t eaten yet, Mandy. From the looks of things, he wouldn’t mind if you sat down again.’

‘Auntie! When I think of all your lectures on…’ she lowered her voice ‘…the dangers of men, and here you are, suggesting I sit with him?’

Aunt Sal surprised Mandy with a wistful smile, making her wonder if there had been a seafaring man in Sal’s life at some point. ‘It’s nearly Christmas and we are at war, Mandy,’ she said simply.

‘That we are,’ Mandy said. ‘I suppose a little kindness never goes amiss.’

‘My thought precisely,’ Sal told her. ‘I reared you properly.’

Mandy backed out of the swinging door with the custard. The master formally indicated the chair opposite him and she sat down, suddenly shy. And sat there.

‘See here, Miss Mathison. Despite what that old fellow thought, I have enough manners not to eat first. Pick up your fork.’

She did as he said, enjoying just the hint of rum that her aunt always added to her custard. In a week, they would spend an afternoon making Christmas rum balls and the tea room would smell like Percival Bartle’s brewery on the next street.

He ate with obvious appreciation, showing no signs of being stuffed beyond capacity. Then he removed the napkin from his uniform front and set down his fork.

‘I have a dilemma, Miss Mathison…’ he began.

‘Most customers call me Mandy,’ she said.

‘I’ve only known you about an hour,’ he replied, ‘but if you like, Mandy it is. By the way, I am Benneit Muir.’ He wiped his mouth. ‘My dilemma is this—Thomas Walthan won’t hear of my staying at Walthan Manor. Apparently I am not high bred enough.’ He chuckled. ‘Well, of course I am not.’

Mandy sighed. ‘That would be the Walthans.’

‘I can probably find a room at the public house, but more than anything, I’d like some peace and quiet to read. Can you suggest a place?’

‘Venable doesn’t…’ she began, then stopped. ‘Let me ask my aunt.’

Aunt Sal was putting away the beef roast. Mandy slid the dishes into the soapy water where soon she would be working, now that luncheon was over.

‘Aunt, his name is Benneit Muir and he has a dilemma.’

Aunt Sal gave her an arch, all-knowing look. ‘Mandy, you have never been so interested in a diner before.’

‘You said it—he’s interesting. Besides, you as much as suggested I be pleasant to him, because it is Christmas.’ She took a good look at her aunt, a pretty woman faded beyond any bloom of youth, but kind, so kind. ‘Apparently he has agreed to tutor Thomas Walthan in mathematics, but you know the Walthans—they won’t allow him to stay there.’

‘No surprise,’ Aunt Sal said as she removed her apron.

‘The posting house is too noisy and he wants quiet to read, when he’s not tutoring. We have that extra room upstairs. What do you think?’

‘A room inches deep in dust.’ Aunt Sal took another peek out the door. ‘We don’t even know him.’

Mandy considered the situation. She had never been one to cajole and beg for things, mainly because she had everything she needed. She didn’t intend to start now, but there was something about the master that she liked.

‘No, we don’t know him,’ Mandy said, picking her way through uncharted water. ‘Maybe he would murder us in our beds. Or shinny down the drainpipe and leave us with a bill.’

‘That seems doubtful, dearest. He just wants peace and quiet? There’s plenty of that here.’

Mandy said no more; she knew her aunt. After a moment in thought, Aunt Sal gave her another long look.

‘On an hour’s acquaintance, you think you know him?’

‘No,’ Mandy replied. She had been raised to be honest. ‘But you always say I am a good judge of character. And besides, didn’t you just encourage me?’

Aunt Sal folded her arms. ‘That chicken is coming home to roost,’ she said. ‘Remind me not to be so soft-hearted in future.’

‘It could also be that I am tired of my half-brother riding roughly over everyone,’ Mandy said softly.

Aunt Sal put her hands on Mandy’s shoulders and they touched foreheads. ‘Should I have started Mandy’s Rose in another village?’

‘No, Aunt. This is our home, too.’

Aunt Sal kissed Mandy’s forehead. ‘Let’s go chat with the sailing master.’

Here comes the delegation, Ben thought, as the door to the kitchen swung open. At least I’m not on a lee shore yet.

This could only be Aunt Sal. He took her in at a glance, a woman past her prime, but lively still and obviously concerned about her niece. He knew he was looking at a careful parent. He got to his feet, swaying a little because he still didn’t have the hang of decks—no, floors—that remained stationary.

She came closer and gave a little nod of her head, which he returned with a slight bow. She moved one of the chairs closer from the nearest table, but Mandy sat at the same table where he had eaten that enormous lunch. That gesture told him whose side Mandy was on and he thought he might win this. It was a game he had never played before, not with war and eighteen years at sea.

‘I am Sally Mathison, proprietor of this tea room. My niece tells me you are looking for quiet lodgings for a few weeks.’

‘Aye,’ he replied. ‘I am Benneit Muir, sailing master of the Albemarle, in dry dock near Plymouth. I’ll be here three weeks, trying to cram mathematics into young Thomas Walthan’s brainbox. It will be a thankless task, I fear, and I would most appreciate a quiet place at night, the better to endure my days.’

‘Is he paying you?’ Sal Mathison asked.

‘Aunt!’ Mandy whispered.

‘No, it’s a good question,’ he said, quietly amused. ‘He is paying me fifty pounds.’

He could tell from the lady’s expression that the tide wasn’t running in his favour, despite Mandy’s soft admonition. Honesty meant more honesty.

‘I’m tired, Miss Mathison. I often just stay with the ship during dry dock, because I am invariably needed because my ship’s duties are heavy. Scotland is too far to go for Christmas, and besides, my mother is dead and my brothers live in Canada. I…I wanted something different. And, no, I do not need the money. I bank regularly with Brustein and Carter in Plymouth.’ That should be enough financial soundness, even for a careful aunt, he thought.

‘I was rude to ask,’ Sal Mathison said.

‘I rather believe you are careful,’ he replied, then put his hands palm up on the table, petitioning her. ‘Just a quiet place. I don’t even know if you have a room to let.’

Hands in her lap, Aunt Sal looked him in the eye for a long moment and he looked back. This wasn’t a lady to bamboozle, not that he had any skill along those lines. He could only state his case.

‘I don’t drink, beyond a daily issue of grog on board. I don’t smoke, because that is dangerous on a ship. I mind my own business. I am what you see before you and, by God, I am tired.’

He knew without looking that Mandy’s eyes would soften at that, because he was a good study of character, a valuable trait in a master. It was Sal Mathison he had to convince.

Her face softened. ‘Right now, the room is thick in dust. It used to be my mother’s room, Mandy’s grandmama.’ Her eyes narrowed and he knew the matter hinged on the next few seconds. She nodded, and he knew he had won. ‘Two shillings a week—that includes your board—paid in advance.’

Happy for the first time in a long while, he withdrew six shillings from his pocket. He handed them to her. ‘I can dust and clean, Miss Mathison.’

‘I’ll let you. Mandy can help. I have to start the evening meal.’ She stood up and he got to his feet as well. She indicated that he follow them into the kitchen.

‘Go upstairs, Mandy, and open those windows. We need to air it out.’

Mandy did as she was bid. Curious, he watched her go to an inside door which must lead to stairs. There it was again—she looked back at him for the briefest moment. He felt another care slide from his shoulders. He looked at Miss Mathison, knowing what was coming.

‘Under no circumstances are you to take advantage of my niece, Master Muir,’ she told him. ‘She is my most precious treasure. Do you understand?’

‘I do.’

‘Then follow me. I have a broom and dustpan.’

He reported upstairs with said broom and accoutrements, left them with Mandy after a courtly bow, then went below deck again for mop and bucket. Mandy’s hair was tied back in a scarf that displayed the even planes of her face. He thought she was past her first bloom, but she still radiated youth. On another day, it might have made him sour to think of his own missed opportunities, thanks to the Beast from Corsica. Today, he felt a little younger than he knew he was. Maybe he could blame such good tidings on the season.

But there she stood, broom in hand, lips pursed.

‘Uh, I paid six shillings for this room,’ he teased, which made her laugh.

‘Master Muir…’ she began.

‘I am Ben if you are Mandy.’

‘Very well, sir.’

‘Ben.’

‘Ben! I’ll dust and then you sweep.’

She dipped the cloth in the mop water, wringing it out well. He watched her tackle the nightstand by the bed, so he did the same to the much taller bureau. He took off his uniform coat and loosened his neckcloth, then tackled the clothes press.

‘Why haven’t you let out this excellent room before?’ he asked, dusting the top of the window sill. He looked out. God be praised, there was a view of the ocean.

‘Auntie and I rattle along quite well without lodgers,’ she told him. ‘Besides, it was Grandmama’s only two years ago, when she died.’ Mandy stopped dusting and caressed the headboard. ‘What a lovely gram she was.’

She started dusting again, whistling under her breath, which Ben found utterly charming. She laughed and said, ‘It’s “Deck the Halls”. You may whistle along, too.’

To his astonishment, he did precisely that. When she sang the last verse in a pretty soprano, complete with a retard on the final la-la-la-la, he sang, too. ‘Do you know “The Boar’s Head” carol?’ he asked.

She did and he mopped through that carol, too, with an extra flourish of the mop on the last ‘Reddens laudes Domino’.

‘We have some talent,’ she said, which made him sit on the bed and laugh. ‘Move now,’ she said, her eyes still bright with fun. ‘The dusty sheets go downstairs.’

He waited in the room until she came back up with clean sheets and they made the bed together.

‘Aunt Sal thinks we’re too noisy,’ Mandy said and she squeezed the pillow into a pillow slip with delicate embroidery, nothing he had ever seen in a public house before. ‘I told her that you will come with me to choir practice tomorrow night at St Luke’s.’ She peered around the pillow, her eyes small again, which he knew meant she was ready to laugh. ‘You will, won’t you? Our choir needs another low tenor in the worst way.’ She plumped the pillow on the bed. ‘Come to think of it, most of what our choir does is in the worst way.’

‘I will be honoured to escort you to St Luke’s,’ Ben replied and meant every syllable.

She gave a little curtsy, and her eyes lingered on his neck, more visible now with the neckcloth loose. He knew she was too polite to ask. He pointed to the blue dots that started below his ear and circled around his neck.

‘The result of standing too close to gunpowder,’ he told her.

‘I hope you never do that again,’ she said. It touched him that she worried about an injury he knew was a decade old.

‘No choice, Mandy. We were boarding a French frigate. As a result, I don’t hear too well out of this ear and my blue tattoo goes down my back.’

She coloured at that bit of information, and Ben knew he should have stopped with the deaf ear.

‘I pinched my finger in the door once,’ she said. ‘I believe we have led different lives.’

‘I know we have,’ he agreed, ‘but I’m ready for Christmas on land.’

‘That we can furnish,’ she assured him, obviously happy to change the subject, which he found endearing. ‘Help me with the coverlet now.’

After the addition of towels and a pitcher and bowl, Mandy declared the room done. ‘Your duffel awaits you downstairs, Master Muir,’ she said, ‘and I had better help with dinner. We’ll eat at six of the clock.’

He followed her down the stairs, retrieved his duffel and walked back upstairs alone. He opened the door and looked around, vaguely dissatisfied. The room was empty without Mandy.

‘You sucked all the air out of the place,’ he said out loud. ‘For six shillings, I should get air.’