Читать книгу Shabash! - Ann Walsh - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеThe first hockey practice was a disaster. To begin with, it was at six in the morning and I had to persuade Babli to do my paper route for me. She hates getting out of bed early, so I had to give her two dollars to do the deliveries. If this kept up, the paper route was going to cost me more than I made!

Coach Bryson had phoned and explained that I would be playing on his team in the Pee Wee division, sponsored by the Legion. He said that we would have quite a few early morning practices because of the difficulty in arranging enough ice-time for all the teams. I wasn’t too sure what “ice-time” meant, but I figured I could manage the early practices, just as long as they didn’t happen too often on the three days a week the newspaper comes out. “That’s okay, sir,” I told the coach. “I can handle it.”

I said I could handle it, but that was before I got to the practice. I’d gone out and bought new skates, expensive ones, and picked up a hockey stick at the same time. I figured I was all set to play hockey.

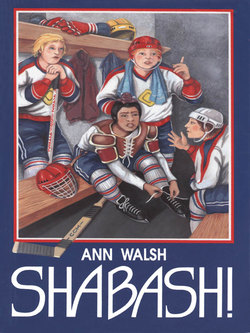

No way! When I walked into the dressing room, the other kids were pulling on shoulder pads, knee pads, thick hockey pants, garter belts and even some stuff I’d never seen before. I knew that the professional players wore all that kind of junk, but I didn’t think the kids in the minor league had to.

There was a moment’s silence when I walked in and all the guys sat there on the bench, not moving, just staring at me. I’d never met Mr. Bryson, only talked to him on the phone, but there was only one adult in the dressing room so I figured it had to be him. But he stood with the rest of the team, staring just as hard.

“Mr. Bryson?” I said, wondering why my voice sounded so thin.

He stepped out from the group and came to me. “Yes,” he said. “I’m Mr. Bryson, your coach. I’m glad you could make it, Ron. Or would you prefer to be called something else? Ron isn’t your…uh…your real name, is it?”

“It’s okay, sir” I said. “Everyone calls me Ron at school.”

“Well then, ‘Ron’ it is. But please don’t call me ‘sir.’ I hate it. Makes me feel like a school teacher or a policeman. Around here, I’m just ‘coach’.” He smiled at me, but it wasn’t a great smile; sort of tight around the edges. I smiled back anyway.

Mr. Bryson looked around the room. “Hey everyone, listen up. This is Ron, Ron Bains. Maybe some of you know him from school?” He looked around, but no one said anything. I looked around, too, but I didn’t recognize any of the other players. They must all be from one of the other schools in town.

“Hi,” I said.

No one said anything back.

“Ron has never played hockey before,” said Coach Bryson, looking around the room again. I thought I heard someone snort, but still no one said anything. “Let’s welcome him to minor hockey and make him feel at home— okay guys?”

Someone said “Hi” in a small voice, but the rest of the team went back to their lacing and strapping and tightening and didn’t say anything. I found an empty spot on a bench and sat down, pulling off my Nikes and taking my skates out of my gym bag. It was awfully quiet in the room. “Big deal,” I said to myself, beginning to put on my skates.

“Uh, Ron, let’s have a look at your equipment. I’m a stickler for the proper equipment; cuts down on injuries and gives the players a good feeling of security.”

“I could do with some of that,” I thought. I wasn’t feeling very secure about anything right now. But out loud I said, “All I have is my skates and a stick. I didn’t know that I had to get anything else.”

“Didn’t I send you an equipment list? I’m sorry, Ron. Everyone else on this team has played minor hockey before, so I knew they’d have the right stuff. I guess that I forgot that you wouldn’t know what you needed.”

Someone giggled and a voice muttered, “Stupid raghead.” The coach turned around, fast, trying to see who had spoken.

“We had a discussion earlier this morning,” he said, “and I made my rules perfectly clear. Anyone who doesn’t obey them is off the team. There’ll be no more of that kind of language!”

“Earlier this morning?” I was puzzled. Earlier than six o’clock when the practice was scheduled to start? Then I suddenly understood. The coach had called the rest of the team together and had talked to them. He’d done it before I got there, because he’d been talking about me.

I stopped lacing up my skate. “Mr. Bryson? I think maybe it would be better if I just go home this morning. You can give me that list and I’ll get the stuff for the next practice.”

If things were going to be so bad that the coach had to make rules about how the other players treated me, I wasn’t going to bother with minor hockey. I’d leave, throw the equipment list away, and not bother coming back. Good thing I hadn’t paid my registration fee yet. I do my own fighting when I have to, but playing hockey didn’t look as if it were going to be worth the effort. Not if the ugly comments had started already and the coach had to lay down rules about me.

“I’ll go home,” I repeated.

“Nonsense, Ron.” Coach Bryson’s voice sounded funny, as if he were not sure he believed what he heard himself saying. He cleared his throat and when he spoke again his voice was stronger. “We’re not doing anything terribly hard this morning, mainly skating drills to start getting everyone back into shape. You can manage without the extra equipment for today. Let’s go.” He turned around and shouted, “All right, everyone. Hit the ice!”

We did. But I “hit” that ice more than anyone else on the team, mostly on my rear end. I had thought I could skate pretty well, but some of those kids must have been wearing skates before they could walk. They were good! Mr. Bryson stood by the side of the rink, a notebook in his hand, watching us. We skated forwards, backwards, in circles and around and around the rink. We hunkered down into squats, lifted one leg and kicked while trying to stay steady on the other foot, jumped over pylons and even “rode” the hockey stick like a witches’ broom, using it as a rudder to steer with.

Coach Bryson kept watching and writing, shouting instructions for the next exercise, occasionally calling out to someone, “Balance! Shoulder over knee, knee over foot! Both hands on the stick. Keep that stick flat on the ice, flat!”

It was only forty-five minutes, but it seemed like hours. My new skates rubbed on my ankles, the seat of my jeans was soaking wet from my attempts at the squatting drills and all the falls I had taken and my hands were so cold they seemed glued to the stick.

Finally Mr. Bryson called us off the ice, passing comments as we filed past him towards the dressing room. “You’ve forgotten how to stop quickly, Les. Work on it. Hey, Brian, nice cross-overs! Ken, your ankles are giving out on you. Let me check your skates before you go. They don’t seem to be giving you much support.”

As I went past him, he patted me on the back. “Good work, Ron,” he said. “You need practice, but you’ve got balance and a lot of flexibility. You’ll be a fine hockey player.”

I couldn’t believe it! It had seemed to me that I had spent most of the time picking myself up off the ice, bumbling around and making a fool of myself. I had believed I could skate well—until I watched the others showing their stuff out there on the ice.

I felt like a total wipe-out, but the coach had said “good work.”

It made me feel better and I headed for the dressing room in a good mood. Sure, I wasn’t the greatest skater, but I would learn. It would take a bit of time, but I could do it. I watched carefully as the others stripped off all the layers of padding, wondering if I’d ever learn how to put all that stuff on. It looked like a lot of equipment to buy and I hoped I had enough money.

“Next practice is Sunday at three. Then we’ll really start working hard.” Mr. Bryson was in the dressing room, checking Ken’s skates. “Ron,” he called to me. “I’ll get you that list of equipment, but for now just make sure you have a good helmet and some gloves. The rest can come later.”

Helmet? The coach and I had the thought at the same moment. I reached up a hand and touched my hair, tied up on top of my head in a white handkerchief. One of the rules of my religion is that no Sikh should cut his hair. The older boys and men wear turbans, but younger boys usually wear their hair tied up on top of their head. We call that knot of hair a “ghuta,” and keep it covered with a cloth about the size of a handkerchief. It’s much easier to put on than the long turban which the adult men wear; learning to wind all that material around and around your head so it stays in place is difficult and takes a lot of practice.

Would a helmet fit over my ghuta? I had no idea. I hadn’t been officially baptized as a Sikh yet, so I supposed I could cut my hair if I had to. But Mom and Dad wouldn’t hear of it. They hadn’t had my hair cut since I was five and I knew they wouldn’t approve of me cutting it now.

Coach Bryson was still looking at my head. “Les,” he called suddenly.

“What?” asked Les. He was the player who’d had so much trouble stopping on the ice. He was as short as me, but he must have weighed a whole lot more.

“Lend Ron your helmet for a minute, Les. We have to see if he can get it on over that hair of his.”

“But, coach!” Les looked up, his eyes wide. “But, coach, I can’t do that!”

“Just for a minute, Les, not for good.”

“I can’t.”

“Can’t, Les? Or won’t? Come on, pass it over.”

“For him to wear? No way!”

“Les! Hand over that helmet!” Mr. Bryson’s face was stern, his voice angry. Everyone else in the room had stopped what they were doing and was staring at us. “Come on, Les. Let’s have the helmet.”

“But my dad…I can’t….” Les’ voice trailed away. Mr. Bryson stood there, his hand outstretched, waiting. Finally Les reached down, picked up his helmet and reluctantly handed it to him.

“Okay Ron,” said the coach. “See how it fits.”

I stood and picked up my gym bag. “It’ s all right, Mr. Bryson. I wouldn’t want Les to feel mat his helmet had been contaminated.”

It’s a good thing that I am so dark skinned, because I was angry, very angry. If I’d had lighter skin, my face would have been bright red—a dead giveaway of how angry I was. I could feel my cheeks burning, but I knew that nothing showed on my face and my voice was calm when I spoke.

“I can buy my own equipment, thanks just the same. I don’t need to try his on. Besides….”—I couldn’t help it, I was furious—“Besides…” I said again, looking down at Les’ huge form, “if his head is as big as the rest of him, his helmet wouldn’t fit me anyway!”

Then I picked up my skates and stick and walked out. Behind me I could hear the rest of the team beginning to laugh.

Les’ voice rose over the noise, whining. “Ah come on you guys, knock it off!”

They were laughing at Les, not at me. I suppose I should have felt sorry for him, but I didn’t.